Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ARTHURENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

119

Bea Arthur

Tony playing Angela Lansbury’s ‘‘bosom buddy’’ Vera Charles in

Mame. She reprised the role in the film version (1974), this time

opposite comedy legend Lucille Ball. Her other films include Lovers

and Other Strangers (1970) and The Floating Lightbulb.

But it is on television that Arthur has created her most enduring

characters. In the early 1970s, she guest-starred on Norman Lear’s

groundbreaking situation comedy All in the Family, playing Edith’s

abrasively opinionated cousin, Maude. Maude was so popular with

viewers that she was spun off into her own Lear series. Finding a

welcoming groove in the early years of women’s liberation, Maude

remained on the air for a six-year run, winning an Emmy for Arthur

for her portrayal of a strong woman who took no guff from anyone.

Tired of the ‘‘yes, dear’’ stereotype of sitcom wives, 1970s audiences

welcomed a woman who spoke her mind, felt deeply, and did not look

like a young model. In her fifties, Arthur, with her graying hair, big

body, and gravelly voice, was the perfect embodiment for the no-

nonsense, middle-aged woman, genuine and believable, as she dealt

with the controversial issues the show brought up. Even hot potato

issues were tackled head-on, such as when an unexpected midlife

pregnancy forces Maude to have an abortion, a move that more

modern situation comedies were too timid to repeat.

After Maude, Arthur made an unsuccessful sitcom attempt with

the dismal Amanda’s, which only lasted ten episodes, but in 1985, she

struck another cultural nerve with the hit Golden Girls. An ensemble

piece grouping Arthur with Estelle Getty, Rue McClanahan (a co-star

from Maude), and Betty White, Golden Girls was an extremely

successful situation comedy about the adventures of a household of

older women. The show had a long first run and widely syndicated

reruns. All of the stars won Emmys, including two for Arthur, who

played Dorothy Sbornak, a divorcee who cares for her elderly

mother (Getty).

Arthur, herself divorced in the 1970s after thirty years of

marriage, has brought her own experiences to the characters that she

has added to the American lexicon. In spite of her exceptional

success, she is a deeply shy and serious person who avoids talk shows

and personal interviews. Though she does not define herself as

political or spiritual, she calls herself a humanitarian and is active in

AIDS support work and animal rights. She once sent a single yellow

rose to each of the 237 congresspeople who voted to end a $2 million

subsidy to the mink industry. In perhaps the ultimate test of her

humanitarian principles, she assisted in her elderly mother’s suicide.

Arthur has become somewhat of a cult figure in the 1990s. The

satirical attention is partially inspired by the movie Airheads (1994)

in which screwball terrorists take over a radio station, demanding,

among other outrageous requests, naked pictures of Bea Arthur.

Bumper stickers with the catch phrase ‘‘Bea Arthur—Be Naked’’ and

ARTHURIAN LEGEND ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

120

a cocktail called Bea Arthur’s Underpants, a questionable combina-

tion of such ingredients as Mountain Dew, vodka, and beer, are some

of the results of Arthur’s cult status.

—Tina Gianoulis

FURTHER READING:

‘‘Bea Arthur.’’ http://www.jps.net/bobda/bea/index.html. March 1999.

Gold, Todd. ‘‘Golden Girls in Their Prime.’’ Saturday Evening Post.

Vol. 255, July-August 1986, 58.

Sherman, Eric. ‘‘Gabbing with the Golden Girls.’’ Ladies Home

Journal. Vol. 107, No. 2, February 1990, 44.

Arthurian Legend

The name of King Arthur resounds with images of knightly

romance, courtly love, and mystical magic. Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere,

Galahad, and Merlin all carry meanings reflecting the enduring

themes of adultery, saintliness, and mysterious wisdom from the

Arthurian legend, which can truly be described as a living legend. The

popularity of the tales of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round

Table, Avalon, Camelot, and the Holy Grail is at a height unrivaled

after more than 1,500 years of history. By the 1990s the legend had

appeared as the theme of countless novels, short stories, films,

television serials and programs, comics, and games.

Some recent writers have attempted to explain why there should

be such a popular fascination with the reworkings of so familiar a

story. Much of the enchantment of Arthur as hero has come from

writers’ ability to shift his shape in accordance with the mood of the

age. C.S. Lewis noted this ability, and compared the legend to a

cathedral that has taken many centuries and many builders to create:

I am thinking of a great cathedral, where Saxon, Nor-

man, Gothic, Renaissance, and Georgian elements all

co-exist, and all grow together into something strange

and admirable which none of its successive builders

intended or foresaw.

In a general view of this ‘‘cathedral’’ as it has evolved into

today, one can see several characteristics of the legend immediately:

it focuses on King Arthur, a noble and heroic person about whom are

gathered the greatest of knights and ladies; who has had a mysterious

beginning and an even more mysterious ending; whose childhood

mentor and foremost adviser in the early days of his reign is the

enchanter Merlin; and who has a sister, son, wife, and friend that

betray him in some fashion, leading to his eventual downfall at a great

battle, the last of many he has fought during his life. Quests are also

common, especially for the Grail, which (if it appears) is always the

supreme quest.

Probably one of the most familiar and successful modern tales of

King Arthur is Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s

Court (1889). At first poorly received, this novel has since established

itself as one of the classics of American literature. Twain’s character-

istic combination of fantasy and fun, observation and satire, confronts

the customs of chivalric Arthurian times with those of the New

World. In it, Hank Morgan travels back in time and soon gains power

through his advanced technology. In the end, Hank is revealed to be as

ignorant and bestial as the society he finds himself in.

In recent times, however, the legend appears most frequently in

mass market science fiction and fantasy novels, especially the latter.

Since the publication of T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone (1938),

it has appeared as the theme in some of the most popular novels,

including Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave (1970), Marion Zimmer

Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon (1982), and Stephen R. Lawhead’s

Pendragon Cycle (1987-1999). For the most part, the fantasy tales

retell the story of Arthur and his knights as handed down through the

centuries. They also build on the twist of magic that defines modern

fantasy. Merlin, therefore, the enigmatic sorcerer, becomes the focus

of most of the novels, particularly Stewart’s and Lawhead’s.

Due to Merlin’s popularity, he has also appeared as the main

character of some recent television serials, including the 1998 Merlin.

Sam Neill is cast as Merlin, son of the evil Queen Mab. He tries to

deny his heritage of magic, but is eventually forced to use it to destroy

Mab and her world, making way for the modern world. This has been

one of the most popular mini-series broadcasts on network television

since Roots (1977) even though Arthur and his knights are barely seen

in this story.

In the movies, however, Merlin fades into the background, with

Hollywood focusing more on Arthur and the knights and ladies of his

court. The first Arthurian film was the 1904 Parsifal from the Edison

Company. It was soon followed by other silent features, including the

first of twelve film and television adaptations of Twain’s Connecticut

Yankee. With the advent of talking pictures, the Arthurian tale was

told in music as well as sound. After World War II and with the arrival

of Cinemascope, the Arthurian tale was also told in full color. Most of

the early movies (including the 1953 The Knights of the Round Table,

Prince Valiant, and The Black Knight), however, were reminiscent of

the western genre in vogue at that time.

In the 1960s two adaptations of T.H. White’s tales, Camelot

(1967) and Disney’s The Sword in the Stone (1965), brought the

legend to the attention of young and old alike. Disney’s movie

introduces Mad Madame Mim as Merlin’s nemesis and spends a great

deal of time focusing on their battles, while Camelot, an adaptation of

the Lerner and Lowe Broadway musical, focuses on the love triangle

between Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere. This was also the theme of

the later movie, First Knight (1995). However, Britain’s Monty

Python comedy troupe made their first foray onto the movie screen

with the spoof Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). This movie

not only satirized all movie adaptations of the Arthurian tale, but took

a swipe at virtually every medieval movie produced by Hollywood

until that time.

It is Twain’s novel, however, that has produced some of the best

and worst of the movie adaptions. Fox’s 1931 version, with Will

Rogers and Myrna Loy, was so successful it was re-released in 1936.

Paramount’s 1949 version, with Bing Crosby, was the most faithful to

Twain’s novel, but was hampered by the fact that each scene seemed

to be a build up to a song from Crosby. Disney entered the fray with its

own unique live-action adaptations, including the 1979 Unidentified

Flying Oddball and 1995’s A Kid in King Arthur’s Court. Bugs

Bunny also got the opportunity to joust with the Black Knight in the

short cartoon A Connecticut Rabbit in King Arthur’s Court (1978),

complete with the obligatory ‘‘What’s up Doc?’’

The traditional Arthurian legend has appeared as the main theme

or as an integral part of the plot of some recent successful Hollywood

movies, including 1981’s Excalibur, 1989’s Indiana Jones and the

Last Crusade, 1991’s The Fisher King, and 1998’s animated feature

The Quest for Camelot. While the Arthurian legend has not always

AS THE WORLD TURNSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

121

been at the fore of these movies, merely being used as a convenient

vehicle, its presence confirms the currency and popularity of Arthur

and his knights.

The legend has not remained fixed to films and books. Other

places where the legend appears include the New Orleans Arthurians’

Ball held at Arthur’s Winter Palace, where Merlin uses his magic

wand to tap a lady in attendance as Arthur’s new queen, and the

Arthurian experience of Camelot in Las Vegas. Also, in the academic

field, an International Arthurian Society was founded in 1949 and is

currently made up of branches scattered all over the world. Its main

focus is the scholarly dissemination of works on the Arthurian world,

and the North American Branch now sponsors a highly respected

academic journal, Arthuriana.

Throughout its long history the Arthurian legend has been at the

fore of emerging technologies: Caxton’s printing press (the first in

England), for example, published the definitive Arthurian tale, Tho-

mas Mallory’s Le Morte D’Arthur. Today the new technology is the

Internet and the World Wide Web. Arthurian scholars of all calibers

have adapted to this new forum, producing some top web sites for the

use of scholars and other interested parties alike. One site, for

example, The Camelot Project, makes available a database of Arthu-

rian texts, images, bibliographies, and basic information. The site can

be found at: http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/cphome.stm.

The legend has been a staple of the fantasy role playing games

from the late 1970s onward. In higher level modules of the popular

Dungeons and Dragons game, characters from the legend appear.

Shari and Sam Lewis created the ‘‘Pillars of Clinschor’’ module

(1983) for the game, where the adventurers had to seize a castle from

Arthurian arch-villainess Morgan Le Fay. With the rise of computer

games, the Arthurian game has entered a new dimension of role-

playing and graphical user interfaces. The Monty Python troupe, for

example, released their Monty Python and the Holy Grail multimedia

game in the mid 1990s, where the player takes Arthur on his quest

through scenes from the movie in search of the Grail and an out-take.

The legend’s prominence in comic books cannot be underrated

either, given that it forms the backdrop of Prince Valiant, one of the

longest running comic strips in America (1937-). Creator Hal Foster

brought the exiled Valiant to Arthur’s court, where he eventually

earned a place at the Round Table. Prince Valiant itself has engen-

dered a movie (1953), games, and novels. Another major comic to

deal with Arthur had him returning to Britain to save the country from

invading space aliens (Camelot 3000, 1982-1985). The success of

these comics have seen some imitations, most poorer than their

originals, but in some instances even these comics have remained

very faithful to the legend.

The popular fascination is not limited to the various

fictionalizations of Arthur. Major works have been devoted to the

search for the man that became the legend. People are curious as to

who he really was, when he lived, and what battles he conclusively

fought. Archaeological and historical chronicles of Britain have been

subjected to as much scrutiny as the literary in search of the elusive

historical Arthur. A recent examination notes that this interest in

Arthur’s historicity is as intense as the interest in his knightly

accomplishments. Yet, the search for the historical Arthur has yet to

yield an uncontroversial candidate; those that do make the short

list appear in cable documentaries, biographies, and debatable

scholarly studies.

Finally, the image of Camelot itself, a place of vibrant culture,

was appropriated to describe the Kennedy years, inviting comparison

between the once and future king and the premature end of the

Kennedy Administration.

King Arthur and the Arthurian Legend are inextricably a part of

popular culture and imagination. At the turn of a new millennium, the

once and future king is alive and well, just as he was at the turn of the

last, a living legend that will continue to amaze, thrill, and educate.

—John J. Doherty

F

URTHER READING:

Doherty, John J. ‘‘Arthurian Fantasy, 1980-1989: An Analytical and

Bibliographical Survey.’’ Arthuriana. Ed. Bonnie Wheeler. March

1997. Southern Methodist University. http://dc.smu.edu/Arthuriana/

BIBLIO-PROJECT/DOHERTY/doherty.html. March 5, 1997.

Harty, Kevin J. ‘‘Arthurian Film.’’ The Arthuriana/Camelot Pro-

ject Bibliographies. Ed. Alan Lupack. April 1997. Universi-

ty of Rochester. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/acpbibs/

bibhome.stm. November 2, 1998.

Harty, Kevin J. Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film. New

York, Garland, 1991.

Lacy, Norris J., editor. The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York,

Garland, 1996.

Lupack, Alan, and Barbara Tepa Lupack. King Arthur in America.

Cambridge, D. S. Brewer, 1999.

Mancoff, Debra, editor. King Arthur’s Modern Return. New York,

Garland, 1998.

Stewart, H. Alan. ‘‘King Arthur in the Comics.’’ Avalon to Camelot,

2 (1986), 12-14.

Thompson, Raymond H. The Return from Avalon: A Study of the

Arthurian Legend in Modern Fiction. Westport, Connecticut,

Greenwood, 1985.

Artist Formerly Known as Prince, The

See Prince

As the World Turns

Four-and-a-half decades after its April 2, 1956, debut, top-rated

daytime soap opera As the World Turns keeps spinning along. Created

by Irna Phillips, whose other soaps include The Guiding Light,

Another World, Days of Our Lives and Love Is a Many-Splendored

Thing, As the World Turns debuted on CBS the same day as The Edge

of Night (which played on CBS through 1975 before moving to ABC

for nine years), and the two were television’s first thirty-minute-long

soap operas, up from the fifteen minutes of previous soaps.

The show is set in the generic Midwestern burg of Oakdale, a

veritable Peyton Place whose inhabitants are forever immersed in sin

and scandal, conquest and confession, deceit and desire. Originally,

the plot lines spotlighted two dissimilar yet inexorably intertwined

families: the middle-income Hughes and the ambitious Lowell clans,

each consisting of married couples and offspring. One of the first plot

ASHCAN SCHOOL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

122

threads involved law partners Jim Lowell and Chris Hughes, with

Edith, the sister of Chris, becoming involved in an affair with married

Jim. The Lowells eventually were written out of the show; however, a

number of characters with the Hughes surname have lingered in the

story lines. Over the years, the plots have been neck-deep in addition-

al extramarital liaisons along with divorces, child custody cases, car

crashes, blood diseases, and fatal falls down stairs—not to mention

murders. The dilemmas facing characters in the late 1990s—‘‘Will

Emily confront her stalker?’’ ‘‘Is David the guilty party?’’ ‘‘Will

Denise develop a passion for Ben?’’—are variations on the same

impasses and emotional crises facing characters decades earlier.

In some cases, five, seven, and nine actors have played the same

As the World Turns characters. However, one performer has become

synonymous with the show: soap opera queen Eileen Fulton, who has

been a regular since 1960. Fulton’s role is the conniving, oft-married

Lisa. Beginning as simply ‘‘Lisa Miller,’’ over the years her name has

been expanded to ‘‘Lisa Miller Hughes Eldridge Shea Colman

McColl Mitchell Grimaldi Chedwy.’’ Don MacLaughlin, who played

Chris Hughes, was the original cast member who remained longest on

the show. He was an As the World Turns regular for just more than

three decades until his death in 1986.

Of the endless actors who have had roles on As the World Turns,

some already had won celebrity but had long been out of the prime-

time spotlight. Gloria DeHaven appeared on the show in 1966 and

1967 as ‘‘Sara Fuller.’’ Margaret Hamilton was ‘‘Miss Peterson’’ in

1971. Zsa Zsa Gabor played ‘‘Lydia Marlowe’’ in 1981. Abe Vigoda

was ‘‘Joe Kravitz’’ in 1985. Claire Bloom was ‘‘Orlena Grimaldi’’

from 1993 through 1995. Robert Vaughn appeared as ‘‘Rick Hamlin’’ in

1995. Valerie Perrine came on board as ‘‘Dolores Pierce’’ in 1998.

Other regulars were movie stars/television stars/celebrities-to-be who

were honing their acting skills while earning a paycheck. James Earl

Jones played ‘‘Dr. Jerry Turner’’ in 1966. Richard Thomas was

‘‘Tom Hughes’’ in 1966 and 1967. Swoosie Kurtz played ‘‘Ellie

Bradley’’ in 1971. Dana Delany was ‘‘Hayley Wilson Hollister’’ in

1981. Meg Ryan played ‘‘Betsy Stewart Montgomery Andropoulos’’

between 1982 and 1984. Marisa Tomei was ‘‘Marcy Thompson

Cushing’’ from 1983 through 1988. Julianne Moore played ‘‘Frannie/

Sabrina Hughes’’ from 1985 through 1988. Parker Posey was ‘‘Tess

Shelby’’ in 1991 and 1992.

As the World Turns was the top-rated daytime soap from its

inception through the 1960s. Its success even generated a brief

nighttime spin-off, Our Private World, which aired on CBS between

May and September 1965. In the early 1970s, however, the ratings

began to decline. On December 1, 1975, the show expanded to one

hour, with little increase in viewership, but the ratings never descend-

ed to the point where cancellation became an option—and the show

was celebrated enough for Carol Burnett to toy with its title in her

classic soap opera parody As the Stomach Turns. From the 1980s on,

the As the World Turns audience remained steady and solid, with its

ratings keeping it in daytime television’s upper echelon. Over the

years, the show has been nominated for various Writers Guild of

America, Soap Opera Digest, and Emmy awards. In 1986-87, it

garnered its first Emmy as ‘‘Outstanding Drama Series.’’

—Rob Edelman

F

URTHER READING:

Fulton, Eileen, as told to Brett Bolton. How My World Turns. New

York, Taplinger Publishing, 1970.

Fulton, Eileen, with Desmond Atholl and Michael Cherkinian. As My

World Still Turns: The Uncensored Memoirs of America’s Soap

Opera Queen. Secaucus, N.J., Birch Lane Press, 1995.

Poll, Julie. As the World Turns: The Complete Family Scrapbook. Los

Angeles, General Publishing Group, 1996.

Ashcan School

The Ashcan School was the first art movement of the new

century in America, and its first specifically modern style. Active in

the first two decades of the twentieth century, Ashcan artists opposed

the formality of conservative American art by painting urban subjects

in a gritty, realistic manner. They gave form to the tough, optimistic,

socially conscious outlook associated with Theodore Roosevelt’s

time. The Ashcan School artists shared a similar muckraking spirit

with contemporary social reformers. Their exuberant and romantic

sense of democracy had earlier been expressed in the poetry of

Walt Whitman.

At a time before the camera had not yet replaced the hand-drawn

sketch, four Philadelphia artist-reporters—William Glackens, John

Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn—gathered around the artist

Robert Henri (1865-1929), first in his Walnut Street studio, then later

in New York. Henri painted portraits in heavy, dark brown brushstrokes

in a manner reminiscent of the Dutch painter Frans Hals. He taught at

the New York School of Art between 1902 and 1912 where some of

his students included the Ashcan artists George Bellows, Stuart

Davis, and Edward Hopper. The artists exhibited together only once,

as ‘‘The Eight’’—a term now synonymous with the Ashcan School—

at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City in 1908. They had formally

banded together when the National Academy of Design refused to

show their works.

Better thought of as New York Realists, the Ashcan artists were

fascinated by the lifestyles of the inhabitants of the Lower East Side

and Greenwich Village, and of New York and the urban experience in

general. Conservative critics objected to their choice of subjects.

Nightclubs, immigrants, sporting events, and alleys were not consid-

ered appropriate subjects for high art. It was in this spirit that the art

critic and historian Holger Cahill first used the term ‘‘Ashcan

School’’ . . . ashcan meaning garbage can . . . in a 1934 book about

recent art.

John Sloan (1871-1951), the most renowned Ashcan artist, made

images of city streets, Greenwich Village backyards, and somewhat

voyeuristic views of women of the city. His most well known

painting, but one which is not entirely typical of his art, is The Wake of

the Ferry II (1907, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.). The

dull blues and greens of the ship’s deck and the steely water

introduced an element of melancholy in what millions of commuters

experienced daily on the Staten Island Ferry. Sloan’s art sometimes

reflected his socialist leanings, but never at the expense of a warm

humanity. Although he made etchings for the left wing periodical The

Masses, he refused to inject his art with ‘‘socialist propaganda,’’ as he

once said.

The reputation of George Luks (1867-1933) rests on the machismo

and bluster of his art and of his own personality. ‘‘Guts! Guts! Life!

Life! That’s my technique!’’ he claimed. He had been an amateur

actor—which undoubtedly helped him in his pose as a bohemian

ASHEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

123

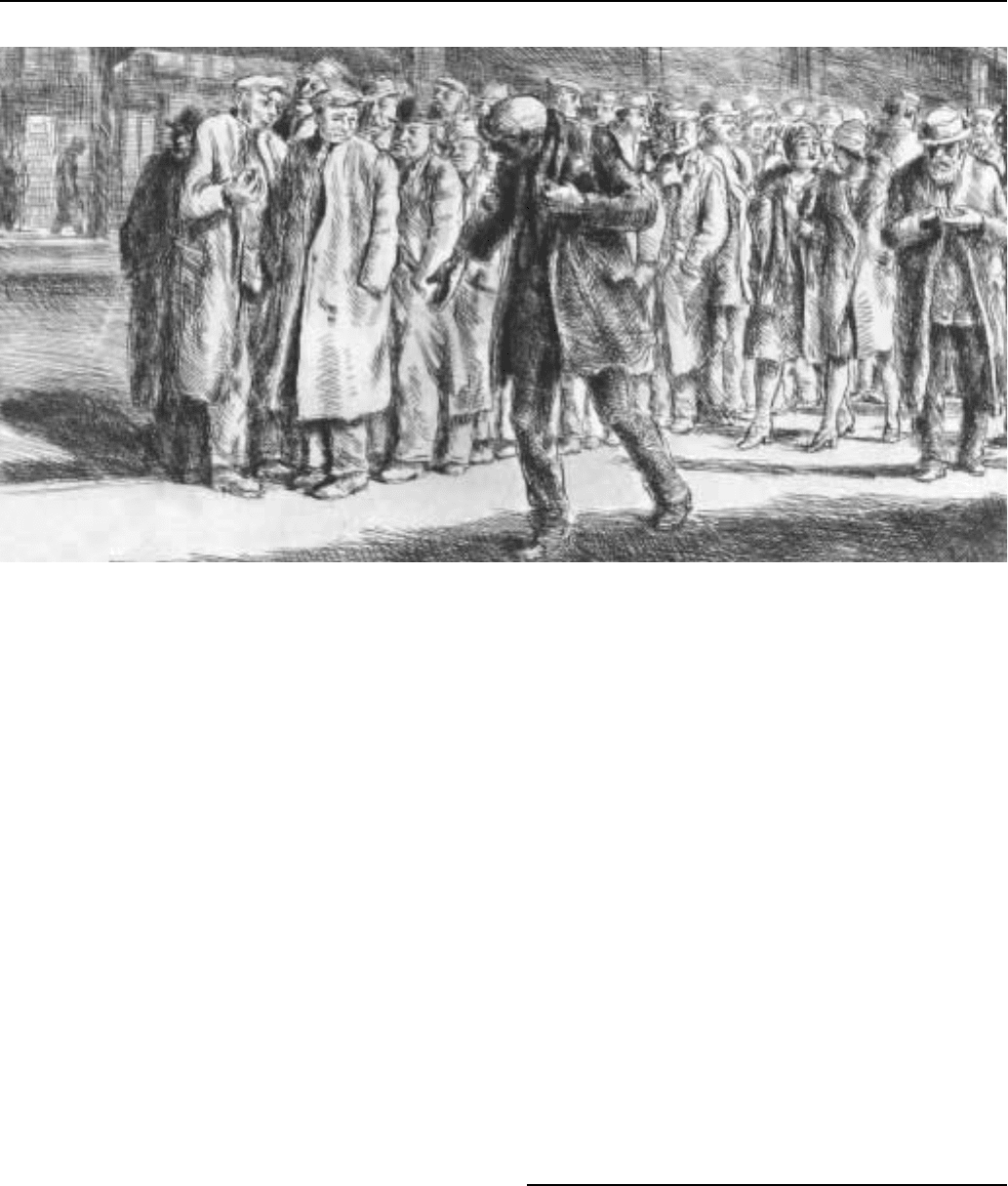

An example from the Ashcan School: Reginald Marsh’s Bread Line.

artist—and had drawn comic strips in the 1890s before meeting Henri

at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His Hester Street

(1905, The Brooklyn Museum) shows Jewish immigrants on the

Lower East Side in an earnest, unstereotypical manner.

George Bellows (1882-1925) was probably the most purely

talented of the group, and made many of the most interesting Ashcan

paintings of the urban environment. An athletic, outgoing personality,

Bellows’ most well known paintings involve boxing matches. Com-

posed of fleshy brushstrokes, Stag at Sharkey’s (1909, Cleveland

Museum of Art) shows a barely legal ‘‘club’’ where drinkers watched

amateur sluggers. Bellows was also an accomplished printmaker and

made more than 200 lithographs during his career.

Much of the art of the Ashcan School has the quality of

illustration. Their heroes included Rembrandt and Francisco Goya, as

well as realists such as Honoré Daumier, Edouard Manet, and the

American Winslow Homer. But not all the Ashcan artists drew their

inspiration from city streets. The paintings of William Glackens

(1870-1938) and Everett Shinn (1876-1953) often deal with the world

of popular entertainment and fashionable nightlife. Glackens’ elegant

Chez Mouquin (1905, Art Institute of Chicago), shows one of the

favorite haunts of the Ashcan artists. Maurice Prendergast (1859-

1924) painted park visitors in a patchy, decorative style. Ernest

Lawson (1873-1939) used a hazy, Impressionist technique to paint

scenes of New York and the Harlem River. The traditional nude

female figures of Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928) seem to owe little to

Ashcan art.

The Ashcan School was not a coherent school nor did the artists

ever paint ashcans. They expanded the range of subjects for American

artists and brought a new vigor to the handling of paint. Their identity

as tough observers of the city, unimpressed by contemporary French

art, changed the way American artists thought of themselves. They

demonstrated that artists who stood apart from the traditional art

establishment could attain popular acceptance. Among their contribu-

tions was their promotion of jury-less shows which gave artists the

right to exhibit with whomever they chose. This spirit of indepen-

dence was felt in the famous 1913 Armory Show in which some of the

organizers were Ashcan artists.

—Mark B. Pohlad

F

URTHER READING:

Braider, Donald. George Bellows and the Ashcan School of Painting.

Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1971.

Glackens, Ira. William Glackens and the Eight: the Artists who Freed

American Art. New York, Horizon Press, 1984.

Homer, William I. Robert Henri and His Circle. Ithaca and London,

Cornell University Press, 1969.

Perlmann, Bennard P. Painters of the Ashcan School: The Immortal

Eight. New York, Dover, 1988.

Zurrier, Rebecca, et al. Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and

Their New York. New York, Norton, 1995.

Ashe, Arthur (1943-1993)

Tennis great and social activist Arthur Ashe is memorialized on

a famous avenue of his hometown of Richmond, Virginia, by a bronze

statue that shows him wielding a tennis racquet in one hand and a

book in the other. Children sit at his feet, looking up at him for

inspiration. Though the statue represents a storm of controversy, with

everyone from racist white Virginians to Ashe’s own wife Jeanne

ASHE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

124

calling it inappropriate, it also represents an effort to capture what it

was that Arthur Ashe gave to the society in which he lived.

Born well before the days of integration in Richmond, the heart

of the segregated south, Ashe learned first-hand the pain caused by

racism. He was turned away from the Richmond City Tennis Tourna-

ment in 1955 because of his race, and by 1961 he left the south,

seeking a wider range of opportunities. He found them at UCLA

(University of California, Los Angeles), where he was the first

African American on the Davis Cup team, and then proceeded to a

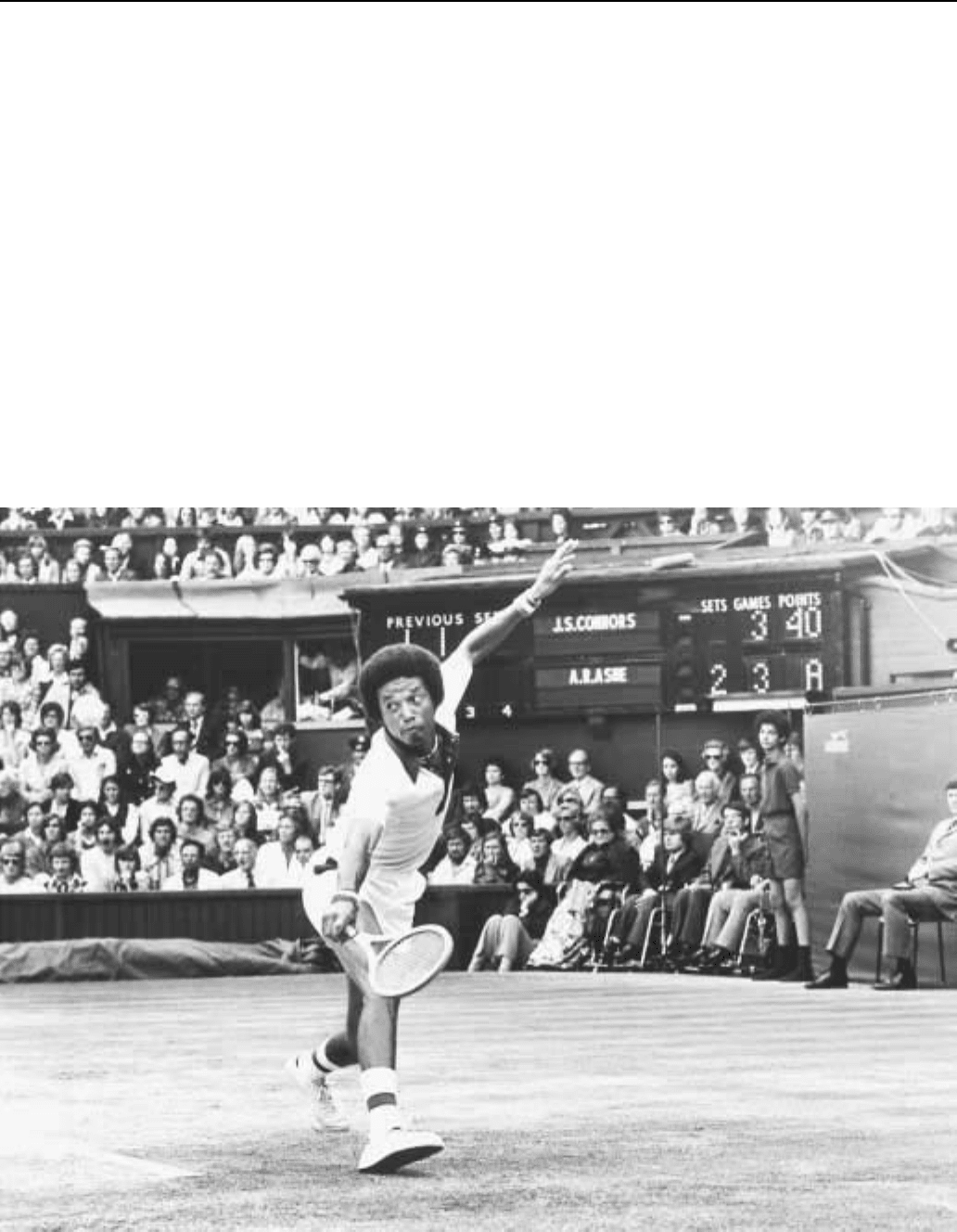

series of ‘‘firsts.’’ In 1968, he was the first (and only) African

American man to win the United States Open; in 1975 he was the first

(and only) African American man to win the men’s singles title at

Wimbleton. He won 46 other titles during his tennis career, paving the

way for other people of color in a sport that still remains largely the

domain of white players.

Ashe was a distinguished, if not brilliant tennis player, but it was

his performance off the court that ensured his place in history. Like

many African Americans raised before integration, Ashe felt that a

calm and dignified refusal to give in to oppression was more effective

than a radical fight. His moderate politics prompted fellow tennis

professional, white woman Billie Jean King, to quip, ‘‘I’m blacker

Arthur Ashe

than Arthur is.’’ But Ashe felt his responsibility as a successful

African American man keenly. He wrote a three volume History of

the American Black Athlete, which included an analysis of racism in

American sports, and he sponsored and mentored many disadvan-

taged young African American athletes himself. He also took his fight

against racism out into the world. When he was refused entry to a

tennis tournament in apartheid South Africa in 1970, Ashe fought

hard to be allowed to enter that intensely segregated country. Once

there he saw for himself the conditions of Blacks under apartheid, and

the quiet moderate became a freedom fighter, even getting arrested at

anti-apartheid demonstrations.

In 1979 Ashe was pushed down the path to his most unwilling

contribution to his times. He had a heart attack, which ended his tennis

career and eventually led, in 1983, to bypass surgery. During surgery,

he received blood transfusions, and it is believed those transfusions

passed the AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) virus into

his blood. Even after he discovered he had AIDS, the intensely private

Ashe had no intention of going public with the information. When the

tabloid newspaper USA Today discovered the news, however, Ashe

had little choice but to make the announcement himself. He was angry

at being forced to make his personal life public, but, as he did in every

ASIMOVENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

125

aspect of his life, he turned his personal experience into public

service. He became an activist in the fight against AIDS, which he

said did not compare to racism as a challenge in his life. It is perhaps

indicative of the stigma attached to the disease that Ashe’s AIDS is

never mentioned without the hastily added disclaimer that he prob-

ably contracted it through a blood transfusion. He was a widely

respected public figure, however, and his presence in the public eye as

a person with AIDS helped to de-stigmatize the disease.

Arthur Ashe died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1993, but his

legacy is durable and widespread. A tennis academy in Soweto, South

Africa, bears his name, as does a stadium in Queens and a Junior

Athlete of the Year program for elementary schools. He helped found

the Association of Tennis Professionals, the first player’s union. And,

only a short time before his death, he was arrested at a demonstration,

this time protesting the United States Haitian immigration policy. He

was a role model at a time when African Americans desperately

needed successful role models. He was a disciplined moderate who

was not afraid to take a radical stand.

The statue of Ashe which stands on Monument Avenue in

Richmond is, perhaps, a good symbol of the crossroads where Ashe

stood in life. The fame of Monument Avenue comes from its long

parade of statues of heroes of the Confederacy. Racist whites felt

Ashe’s statue did not belong there. Proud African Americans, the

descendants of slavery, felt that Ashe’s statue did not belong there.

Ashe’s wife Jeanne insists that Ashe himself would have preferred the

statue to stand outside an African American Sports Hall of Fame he

wished to found. But willingly or not, the statue, like the man, stands

in a controversial place in history, in a very public place, where

children look up at it.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Kallen, Stuart A. Arthur Ashe: Champion of Dreams and Motion.

Edina, Minnesota, Abdu and Daughters, 1993.

Lazo, Caroline Evensen. Arthur Ashe. Minneapolis, Lerner Publica-

tions, 1999.

Martin, Marvin. Arthur Ashe: Of Tennis and the Human Spirit. New

York, Franklin Watts, 1999.

Wright, David K. Arthur Ashe: Breaking the Color Barrier in Tennis.

Springfield, New Jersey, Enslow Publishers, 1996.

Asimov, Isaac (1920-1992)

Scientist and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov made his

reputation in both fields with his prolific writings and his interest in

the popularization of science. Asimov published over three hundred

books and a considerable number of short stories, essays, and col-

umns. He is considered to be a founding figure in the field of science

fiction in his rejection of the space-adventure formula in favor of a

more directly scientific, social, and political aproach. He established

several central conventions for the genre, including robotics and the

idea of a galactic empire. Asimov was also extremely influential

through his nonfiction writings, producing popular introductory texts

and textbooks in biochemistry.

Isaac Asimov

Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russia, on January 2, 1920, and

moved to America with his family when he was three years old. He

first discovered science fiction through the magazines sold in his

father’s candy store, and in 1938 he began writing for publication. He

sold his story ‘‘Marooned Off Vesta’’ to Amazing Stories the follow-

ing year, when he was an undergraduate at Columbia University. That

same year, he sold his story ‘‘Trends’’ to John W. Campbell, Jr.,

editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and it was through his creative

relationship with Campbell that Asimov developed an interest in the

social aspects of science fiction.

Campbell’s editorial policy allowed Asimov to pursue his inter-

est in science fiction as a literature that could respond to problems

arising in his contemporary period. In ‘‘Half-Breed’’ (1941), for

example, he discussed racism, and in ‘‘The Martian Way,’’ he voiced

his opposition to McCarthyism. Asimov’s marked ambivalence about

the activities of the scientific community is a major characteristic of

his writing. Later novels examined the issue of scientific responsibili-

ty and the power struggles within the scientific community. Asimov

himself was a member of the Futurians, a New York science-fiction

group which existed from 1938 to 1945 and was notable for its radical

politics and belief that science fiction fans should be forward-looking

and help shape the future with their positive and progressive ideas.

Asimov spent the Second World War years at the U.S. Naval Air

Experimental Station as a research scientist in the company of fellow

science-fiction writers L. Sprague de Camp and Robert Heinlein. He

made a name for himself as a writer in 1941 with the publication of

‘‘Nightfall,’’ which is frequently anthologized as an example of good

science fiction and continues to top readers’ polls as their favorite

ASNER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

126

science fiction story. During this period, Asimov also started work on

the series of stories that would be brought together as the ‘‘Founda-

tion Trilogy’’ and published as the novels Foundation (1951), Foun-

dation and Empire (1952), and Second Foundation (1953). Asimov

has stated that their inception came from reading Gibbon’s Decline

and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Asimov’s other significant series comprises his robot stories,

collected in I, Robot (1950), The Rest of the Robots (1964), and

further collections in the 1980s. Two novels—The Caves of Steel

(1954) and The Naked Sun (1956)—bring together a detective and his

robotic partner, fusing Asimov’s interest in mystery with his interest

in science fiction. He also wrote several stories about the science

fiction detective Wendell Worth during the same period. It is the third

story of the robot series, ‘‘Liar!’’ (1941), that introduced ‘‘The Three

Laws of Robotics,’’ a formulation that has had a profound effect upon

the genre.

In 1948 Asimov received his doctorate in biochemistry and a

year later took up a position with the Boston University School of

Medicine as an associate professor. He remained there until 1958

when he resigned the post in order to concentrate on his writing

career. He remained influential in the sci-fi genre by contributing a

monthly science column to The Magazine of Science Fiction and

Fantasy for the next thirty years, but his aim during this period was to

produce popular and accessible science writing. During the 1950s he

had published juvenile fiction for the same purpose under the pseudo-

nym of Paul French. In 1960 he published The Intelligent Man’s

Guide to Science, which has gone through several editions and is now

known as Asimov’s New Guide to Science. In the interest of popular

science he also produced a novelization in 1966 of the film Fantastic

Voyage. However, he also wrote in vastly different fields and pub-

lished Asimov’s Guide to the Bible in 1968 and Asimov’s Guide to

Shakespeare in 1970.

Asimov returned to science-fiction writing in 1972 with the

publication of The Gods Themselves, a novel that was awarded both

the Hugo and Nebula Awards. In this later stage of his career Asimov

produced other novels connected with the ‘‘Foundation’’ and ‘‘Ro-

bot’’ series, but he also published novels with new planetary settings,

such as Nemesis in 1989. His influence continued with his collections

of Hugo Award winners and the launch of Isaac Asimov Science

Fiction Magazine in 1977. Overall his contribution lies in his thought-

provoking attitude to science and its place in human society. Asimov

helped transform immediate postwar science fiction from the space

formula of the 1930s into a more intellectually challenging and

responsible fiction. He died of heart and kidney failure on April 6, 1992.

—Nickianne Moody

F

URTHER READING:

Asimov, Isaac. I, Asimov: A Memoir. New York, Doubleday, 1994.

Gunn, James. Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction.

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1982; revised, Lanham, Mary-

land, Scarecrow Press, 1996.

Miller, Marjorie Mithoff. Isaac Asimov: A Checklist of Works Pub-

lished in the United States. Kent, Ohio, Kent State University

Press, 1972.

Olander, Joseph D., and Martin H. Greenberg, editors. Isaac Asimov.

New York, Taplinger, 1977.

Slusser, George. Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of His Science

Fiction. New York, Borgo Press, 1979.

Touponce, William F. Isaac Asimov. Boston, Twayne Publishers, 1991.

Asner, Ed (1929—)

Ed Asner is an award winning actor who holds the distinction of

accomplishing one of the most extraordinary transitions in television

programming history: he took his character Lou Grant—the gruff,

hard drinking, but lovable boss of the newsroom at WJM TV

Minneapolis on the Mary Tyler Moore Show, a half-hour situation

comedy—to the city editorship of the Los Angeles Tribune, on the one

hour drama Lou Grant. Lou Grant’s 12-year career on two successful,

but very different, television shows established Asner as a major

presence in American popular culture.

Yitzak Edward Asner was born on November 15, 1929 in

Kansas City, Kansas. After high school, he attended the University of

Chicago, where he appeared in student dramatic productions and

firmly decided upon a life in the theater. After graduation and two

years in the army, he found work in Chicago as a member of the

Ed Asner

ASTAIRE AND RODGERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

127

Playwrights’ Theater Club. He then headed for New York to try his

luck on Broadway.

His success on Broadway was middling at best. He appeared in

Face of a Hero with Jack Lemmon, and in a number of off-Broadway

productions, as well as several New York and American Shakespeare

Festivals in the late 1950s. In 1961, he packed up his family and

moved to Hollywood. His first film was the Elvis Presley vehicle Kid

Galahad, a remake of the 1937 Edward G. Robinson/Bette Davis/

Humphrey Bogart film. Following this were featured roles in such

films as The Satan Bug (1965), El Dorado (1965), and Change of

Habit (1969), Elvis Presley’s last film. He also performed guest

appearances in numerous television series, and he had a continuing

role as a crusading reporter on the short-lived Richard Crenna series,

Slattery’s People.

In early 1969, Moore and Dick Van Dyke, stars of television’s

The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-1966), appeared in a reunion special

on CBS that did so well in the ratings that the network offered Moore

the opportunity to come up with a series. Together with her husband,

Grant Tinker, and writers James L. Brooks and Allan Burns, she

created The Mary Tyler Moore Show, one of the happiest and most

successful marriages of writing and ensemble casting in the history of

American television. The program was first telecast on September 19,

1970 and centered around Mary Richards, an unmarried, independent

30-year-old woman who was determined to succeed on her own. She

became the assistant producer in the newsroom at fictional WJM-TV

in Minneapolis. Asner was cast as Lou Grant, the gruff and abrupt but

sentimental boss of the somewhat wacky newsroom crew and their

inept news anchor, Ted Baxter, played by Ted Knight. Lou Grant

constantly struggled to maintain a higher than mediocre level of

standards in the newsroom, while he coped with his personal prob-

lems and the problems created by the interaction of the members of

the newsroom crew. His blustery, realistic approach to the job, and his

comedic resort to the ever-present bottle in his desk drawer to vent his

frustration and mask his vulnerability, nicely balanced Mary Richards’

more idealistic, openly vulnerable central character.

Asner was a perennial nominee for Emmy awards for the role,

receiving the Best Supporting Actor awards in 1971, 1972, and 1975.

When the show ended its spectacular run in 1977, Asner was given the

opportunity to continue the role of Lou Grant in an hour-long drama

series that MTM Productions, Moore and Tinker’s production com-

pany, was working up. In the last episode of The Mary Tyler Moore

Show, station WJM was sold and the entire newsroom crew was fired

except, ironically, Ted Baxter. Lou Grant, out of a job, went to Los

Angeles to look up an old Army buddy, Charlie Hume, who, it turned

out, was managing editor of the Los Angeles Tribune. Lou was hired

as city editor. The series was called simply Lou Grant and it presented

weekly plots of current social and political issues torn from the

headlines and presented with high production values. It emphasized

the crusading zeal of the characters to stamp out evil, the conflicts and

aspirations of the reporters, the infighting among the editors, and the

relationship between Grant and the publisher Mrs. Pynchon, played

by Nancy Marchand. The program succeeded because of Asner’s

steady and dominating portrayal of the show’s central character, who

represented a high standard of professional ethics and morals, and

who was often in conflict with the stubborn and autocratic Mrs.

Pynchon. Asner was again nominated for Emmy awards, winning the

award in 1978 and 1980 as Best Actor in a Series.

In 1982, CBS suddenly canceled Lou Grant, ostensibly for

declining ratings, but Asner and other commentators insist that the

show was canceled for political reasons. He was a leading figure in

the actor’s strike of 1980 and was elected president of the Screen

Actors’ Guild in 1981, a post he held until 1985. He also was an

outspoken advocate of liberal causes and a charter member of

Medical Aid for El Salvador, an organization at odds with the Reagan

Administration’s policies in Central America. This created controver-

sy and led to political pressure on CBS to rein in the Lou Grant show

which, to many observers, was becoming an organ for Asner’s liberal

causes. ‘‘We were still a prestigious show. [The controversy] created

demonstrations outside CBS and all that. It was 1982, the height of

Reagan power,’’ he would recall later in an interview on Canadian

radio. ‘‘I think it was in the hands of William Paley to make the

decision to cancel it.’’

Following Lou Grant, Asner has done roles in Off the Rack

(1985) and Thunder Alley (1994-1995). With Bette Midler, he played

a wonderfully subdued role as Papa in the made for television

rendition of Gypsy (1993). In addition to the five Emmies noted

above, he won Best Actor awards for the CBS miniseries Rich Man,

Poor Man (1976) and Roots (1977), a total of seven Emmy awards on

15 nominations. In addition, he holds five Golden Globe Awards and

two Critics Circle Awards.

—James R. Belpedio

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present. New York,

Ballantine Books, 1995.

Brooks, Tim. The Complete Directory to Prime Time TV Stars, 1946-

Present. New York, Ballantine, 1987.

CJAD Radio Montreal. Interview with Ed Asner. Transcript of an

interview broadcast May 12, 1995, http://www.pubnix.net/~peterh/

cjad09.htm.

Astaire, Fred (1899-1987), and

Ginger Rogers (1911-1995)

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were the greatest dance team in

the history of American movies. In the course of developing their

partnership and dancing before the movie camera they revolutionized

the Hollywood musical comedy in the 1930s. Though their partner-

ship only lasted for six years and nine films between 1933 and 1939,

with a tenth film as an encore ten years later, they definitively set the

standards by which dancing in the movies would be judged for a long

time to come. Although they both had independent careers before and

after their partnership, neither ever matched the popularity or the

artistic success of their dancing partnership.

The dancing of Astaire and Rogers created a style that brought

together dance movements from vaudeville, ballroom dancing, tap

dancing, soft shoe, and even ballet. Ballroom dancing provided the

basic framework—every film had at least one ballroom number. But

tap dancing provided a consistent rhythmic base for Astaire and

Rogers, while Astaire’s ballet training helped to integrate the upper

body and leaps into their dancing. Because Astaire was the more

accomplished and experienced dancer—Rogers deferred to him and

imitated him—they were able to achieve a flawless harmony. ‘‘He

gives her class and she gives him sex,’’ commented Katherine

Hepburn. Astaire and Rogers developed their characters through the

ASTAIRE AND RODGERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

128

drive to dance that they exhibited and the obstacles, spatial distances,

and social complications they had to surmount in order to dance.

‘‘Dancing isn’t the euphemism for sex; in Astaire-Rogers films it is

much better,’’ wrote critic Leo Braudy. In their performances, Fred

Astaire and Ginger Rogers suggested that dance is the perfect form of

movement because it allows the self to achieve a harmonious balance

between the greatest freedom and the most energy.

Astaire was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1899. By the age of

seven he was already touring the vaudeville circuit and made a

successful transition to a dancing career on Broadway with his sister

Adele in 1917. After Adele married and retired from the stage in 1932,

Astaire’s career seemed at a standstill. Despite the verdict on a screen

test—‘‘Can’t act. Slightly bald. Can dance a little’’—he made his first

film appearance in Dancing Lady (1933) opposite Joan Crawford.

Rogers, born in 1911 in Independence, Missouri, made her perform-

ing debut as a dancer in vaudeville—under the tutelage of her

ambitious ‘‘stage’’ mother—at age 14. She first performed on Broad-

way in the musical Top Speed in 1929, and two years later headed out

to Hollywood. She was under contract to RKO where she began her

legendary partnership with Fred Astaire.

When sound came to film during the late 1920s, Hollywood

studios rushed to make musicals. This created vast opportunities for

musical comedy veterans like Astaire and Rogers. From the very

beginning Astaire envisioned a new approach to filmed dancing and,

together with Rogers, he exemplified a dramatic change in the

cinematic possibilities of dance. Initially, the clumsiness of early

cameras and sound equipment dictated straight-on shots of musical

dance numbers from a single camera. These straight-on shots were

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers

broken by cutaways which would focus on someone watching the

dance, then on the dancer’s feet, next to someone watching, then back

again to the dancer’s face, concluding—finally—with another full-on

shot. Thus, dances were never shown (or even filmed) in their

entirety. Because of this, Busby Berkeley’s big production numbers

featured very little dancing and only large groups of dancers moving

in precise geometric patterns.

Astaire’s second movie, Flying Down to Rio (1933), was a

glorious accident. It brought him together with Ginger Rogers. It also

brought together two other members of the team that helped make

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers the greatest dance partnership in

American movies—Hermes Pan who became Astaire’s steady cho-

reographic assistant, and Hal Borne, Astaire’s rehearsal pianist and

musical arranger. Before Flying Down to Rio, no one had ever seen an

entire dance number on the screen. Starting with the famous ‘‘Carioca’’

number, Astaire and Pan began insisting that numbers should be shot

from beginning to end without cutaways. Pan later related that when

the movie was previewed ‘‘something happened that had never

happened before at a movie.’’ After the ‘‘Carioca’’ number, the

audience ‘‘applauded like crazy.’’

The success of Flying Down to Rio and the forging of Astaire and

Rogers’ partnership established a set of formulas which they thor-

oughly exhausted over the course of their partnership. In their first six

films, as Arlene Croce has noted, they alternated between playing the

lead romantic roles and the couple who are the sidekicks to the

romantic leads. Their second film, The Gay Divorcee (1934), was

based on Astaire’s big Broadway hit before he decided to go to

Hollywood. It provides the basic shape of those movies in which

Astaire and Rogers are the romantic leads—boy wants to dance with

girl, girl does not want to dance with boy, boy tricks girl into dancing

with him, she loves it, but she needs to iron out the complications.

They consummate their courtship with a dance. Most Astaire and

Rogers movies also played around with social class—there is always

a contrast between top hats, tails, and evening gowns, and even their

vernacular dance forms aimed at a democratic egalitarianism. These

films were made in the middle of the Great Depression when movies

about glamorous upper class people often served as a form of escape.

Dancing is shown both as entertainment and an activity that unites

people from different classes.

The standard complaint about Astaire and Rogers movies are

that they do not have enough dancing. Amazingly, most of their

movies have only about ten minutes of dancing out of roughly 100

minutes of running time. There are usually four to seven musical

numbers in each film, although not all of them are dance numbers. On

the average, a single dance takes approximately three minutes.

Certainly, no one would ever watch most of those movies if they were

not vehicles for the dancing of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. That

these movies find viewers on the basis of no more than ten or 12

minutes of dancing suggests the deep and continuing pleasure that

their performances give.

Each movie assembled several different types of dance numbers

including romantic duets, big ballroom numbers, Broadway show

spectacles, challenge dances, and comic and novelty numbers. In the

best of the movies the song and dance numbers are integrated into the

plot—Top Hat (1935), Swing Time (1936), Shall We Dance (1937).

The centerpiece of most movies was the romantic duet. The incompa-

rable ‘‘Night and Day’’ in The Gay Divorcee was the emotional

turning point of the movie’s plot. Other romantic duets like ‘‘Cheek to

Cheek’’ in Top Hat and ‘‘Waltz’’ in Swing Time, are among the great

romantic dance performances in movies. Some of the movies tried to