Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BARTONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

179

Theater critic Harold Clurman once suggested that John Barrymore

‘‘had everything an actor should ideally possess: physical beauty, a

magnificent voice, intelligence, humor, sex appeal, grace and, to

boot, a quotient of the demonic—truly the prince of players. There

was unfortunately also a vein of self-destructiveness in him.’’ In

retrospect, the ignoble aspects of Barrymore’s life—an extravagantly

wasteful lifestyle, alcoholic binges, four failed marriages, numerous

affairs, self-parodying performances—only contributed to his larger-

than-life status. Though Barrymore the man passed on decades ago,

Barrymore the myth has lost little of its power to captivate.

—Martin F. Norden

F

URTHER READING:

Clurman, Harold. ‘‘The Barrymore Family.’’ Los Angeles Times.

May 1, 1977, C16.

Fowler, Gene. Good Night, Sweet Prince: The Life and Times of John

Barrymore. New York, Viking, 1943.

Kobler, John. Damned in Paradise: The Life of John Barrymore. New

York, Atheneum, 1977.

Norden, Martin F. John Barrymore: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport,

Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1995.

Peters, Margot. The House of Barrymore. New York, Knopf, 1990.

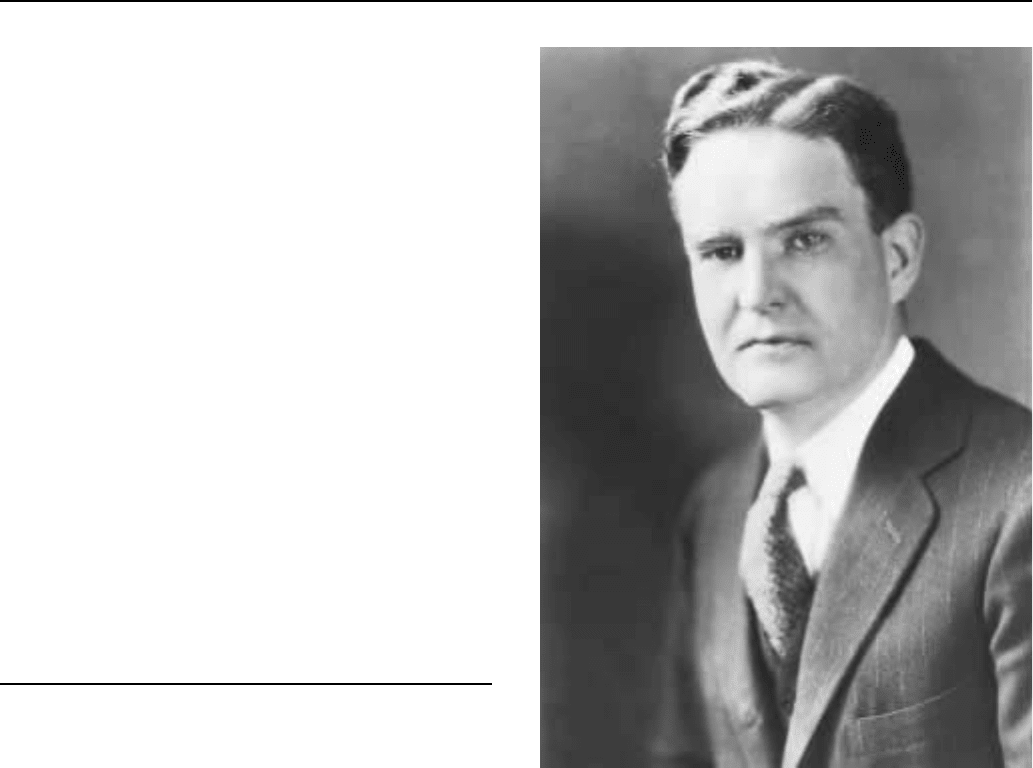

Barton, Bruce (1886-1967)

Advertizing man, religious writer, and United States Congress-

man, the name of Bruce Barton is synonymous with the advertising

firm of Batten, Barton, Durstine, and Osborne, the agency Barton

helped found in 1919. The firm’s clients, including U.S. Steel,

General Electric, General Motors, and Dunlop, were among the most

powerful businesses of the American 1920s. Barton is best remem-

bered for his bestselling book The Man Nobody Knows (1925), a

conduct manual for American businessmen whose subtitle pro-

claimed itself ‘‘a discovery of the real Jesus.’’

The son of a prominent Congregational Minister, Barton was in

the vanguard of the new advertising culture of the 1920s. In a period

where the shift into a ‘‘mass’’ consumption economy had spawned a

new service and leisure economy, advertising became an industry in

its own right and led the way in reshaping the traditional Protestant

morality of Victorian America into something more suited to the

dictates of a modern consumer economy. Of those engaged in such

work Barton was the most renowned. Orthodox Protestant values

emphasized hard work, innate human sinfulness, and the evils of self-

indulgence and idleness. These were not values that could be easily

accommodated within a new commercial world which promoted the

free play of conspicuous personal consumption and the selling of

leisure. In a string of books and articles published across the decade

Barton examined what he claimed were the New Testament origins of

monopoly capitalism, arguing that the repression of desire, and the

failure of the individual to pursue personal self-fulfillment (in private

acts of consumption), were the greatest of all sins. His most famous

book, The Man Nobody Knows, turned the life of Jesus into a template

for the new commercial practices of the 1920s, citing the parables

(‘‘the most powerful advertisements of all time’’) alongside the

insights of Henry Ford and J.P. Morgan. By making Jesus like a

Bruce Barton

businessman, Barton made businessmen like Jesus. This reassuring

message sat easily with the colossal extension of the market into all

areas of American life during the 1920s, and The Man Nobody Knows

itself sold 750,000 copies in its first two years. A follow up, The Book

Nobody Knows (1926), and two subsequent studies in the same idiom,

The Man of Galilee (1928), and On the Up and Up (1929), failed to

sell in the same quantities.

Barton’s writing can also be considered alongside the populariz-

ing of psychoanalysis which took place in the 1920s, an explosion of

interest in ‘‘feel good,’’ ‘‘self help’’ publishing which stressed the

power of the individual mind over material circumstances. Again, this

‘‘feel good’’ message sold well in a time of rapid economic transfor-

mation and subsequent collapse in the 1930s, and the cultural histori-

an Ann Douglas has numbered The Man Nobody Knows in a lineage

which runs from Emile Coue’s Self-Mastery Through Conscious

Auto-Suggestion (1923), through Walter Pitkin’s Life Begins at Forty

(1932), to Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence

People (1936).

In the 1930s Barton launched a brief political career, running for

Congress successfully in 1936, before returning to Batten, Barton,

Durstine, and Osborne in 1940. He remained chairman of the firm

until his retirement in 1961.

—David Holloway

BARYSHNIKOV ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

180

FURTHER READING:

Barton, Bruce. The Man Nobody Knows: A Discovery of the Real

Jesus. Indianapolis and New York, Bobbs-Merrill, 1925.

Douglas, Ann. Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s.

London, Picador, 1996.

Ewen, Stuart. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social

Roots of the Consumer Culture. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1977.

Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a

New American Culture. New York, Vintage, 1994.

Marchant, Roland. Advertizing the American Dream: Making Way

for Modernity, 1920-1940. Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1986.

Strasser, Susan. Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the Ameri-

can Mass Market. New York, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Baryshnikov, Mikhail (1948—)

One of the greatest ballet dancers of the twentieth century,

Baryshnikov overcame initial expectations that his stocky build, short

height, and boyish demeanor precluded him from performing the

romantic roles in ballets like Giselle and Sleeping Beauty. After

leaving the Soviet Union in 1973, however, Baryshnikov joined the

American Ballet Theater (ABT) and became its most celebrated

performer. Throughout his career, Baryshnikov has striven to explore

Mikhail Baryshnikov

new choreography. One major achievement was the collaboration

with choreographer Tywla Tharp, who created for him, among other

works, the incredibly popular Push Comes to Shove. He left ABT to

work with the great Russian-born choreographer George Balanchine

at the New York City Ballet. Baryshnikov soon returned to ABT as its

artistic director where he eliminated its over-reliance on internation-

ally famous guest soloists, developed new repertory, and sought to

promote soloists and lead dancers already a part of ABT. His

charisma, spectacular dancing, and tempestuous love life contributed

greatly to the popularity of ballet in the United States.

—Jeffrey Escoffier

F

URTHER READING:

Joan Accocella. ‘‘The Soloist.’’ New Yorker. January 19, 1998.

Baseball

Originally an early nineteenth century variation of a venerable

English game, baseball, by the late twentieth century, had developed

into America’s ‘‘national pastime,’’ a game so indelibly entwined

with American culture and society that diplomat Jacques Barzun once

remarked, ‘‘Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America

had better learn baseball.’’

Baseball lore places the origins of baseball in Cooperstown, a

small town in upstate New York, where Abner Doubleday, a West

Point cadet and Civil War hero, allegedly invented the bat-and-ball

game in 1839. In reality, the sport was neither new nor indigenous.

The game that ultimately developed into modern baseball was in fact

a modified version of rounders, an English sport imported to the

colonies prior to the American Revolution. Early forms of baseball

were remarkably similar to rounders. Both games involved contend-

ing teams equipped with a ball as well as a bat with which to hit the

ball. In addition, both baseball and rounders required the use of a level

playing field with stations or bases to which the players advanced in

their attempts to score.

Baseball quickly evolved from the sandlot play of children to the

organized sport of adults. In 1845, a group of clerks, storekeepers,

brokers, and assorted gentlemen of New York City, under the

direction of bank clerk Alexander Joy Cartwright, founded the first

baseball club in the United States—the New York Knickerbockers,

which played its games at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey.

The club was more a social association than an athletic one, providing

opportunities to play baseball, as well as hosting suppers, formal

balls, and other festivities. Individuals could become members only

through election. By the 1850s, a number of clubs patterned on the

Knickerbocker model appeared throughout the Northeast and in some

areas of the Midwest and Far West.

The need for codified orderly play had prompted clubs such as

the Knickerbockers to draft rules for the fledgling sport. In 1857, a

National Association of Baseball Players formed to unite the dispa-

rate styles of play throughout the country into a universal code of

rules. Initially, the National Association attracted only New York

clubs, and so the popular ‘‘Knickerbocker’’ style of baseball pre-

dominated. This version of the sport represented a decided evolution

from rounders and resembled modern baseball in form. While no

umpire as yet called balls or strikes in the Knickerbocker game, a

BASEBALLENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

181

A baseball game between the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox.

batter was retired when he swung at and missed three pitches. The

Knickerbocker rules limited a team at-bat to only three outs, and

replaced ‘‘plugging,’’ a painful practice by which a fielder could

retire a base runner by hitting him with a thrown ball, with ‘‘tagging,’’

simply touching a base runner with the ball. Within four years of its

founding, the National Association came to include clubs in New

Haven, Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. These

clubs, for the most part, renounced their local variations on the sport

and took up the ‘‘Knickerbocker’’ style of play.

After the Civil War, the ‘‘fraternal’’ club game took a decidedly

commercial turn. Rather than relying exclusively on club member-

ship to finance their teams, clubs began to earn money by charging

admission to games. In order to maximize gate fees, clubs inclined

away from friendly games played among club members, and turned

more and more to external contests against clubs in other regions. At

the same time, to guarantee fan interest, clubs felt increasing pressure

to field the most highly skilled players. They began to recruit

members based on talent, and, for the first time, offered financial

remuneration to prospective players. In 1869, the Cincinnati Red

Stockings fielded an entire team of salaried players—the first profes-

sional baseball squad in American history.

As more clubs turned professional, a league structure emerged to

organize competition. In 1871, ten teams formed the National Asso-

ciation of Professional Baseball Players, a loose confederation de-

signed to provide a system for naming a national championship team.

The National League, formed five years later, superseded this alli-

ance, offering a circuit comprised of premier clubs based in Boston,

Hartford, Philadelphia, New York, St. Louis, Chicago, Cincinnati,

and Louisville. A host of competing leagues arose, among them the

International League and the Northwestern League, but it was not

until 1903 that the National League recognized the eight-team Ameri-

can League as its equal. Beginning that year, the two leagues

concluded their schedules with the World Series, a post-season play-

off between the two leagues.

Despite the game’s increased commercialization, baseball, in

the early years of the twentieth century, developed into the American

national game. Players such as Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson as well

as managers like Connie Mack and John McGraw approached the

BASEBALL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

182

game in a scientific manner, utilizing various strategies and tactics to

win ball games; in the process, they brought to the game a maturity

and complexity that increased the sport’s drama. The construction of

great ballparks of concrete and steel and the game’s continuing power

to bind communities and neighborhoods together behind their team

further solidified the coming of age of professional baseball. Baseball

had achieved a new institutional prominence in American life. Boys

grew up reading baseball fiction and dreaming of becoming diamond

heroes themselves one day. The World Series itself became a sort of

national holiday, and United States chief executives, beginning with

William Howard Taft in 1910, ritualized the commencement of each

new season with the ceremonial throwing of the first ball.

The appeal of the game had much to do with what many

considered its uniquely American origins. ‘‘It’s our game—that’s the

chief fact in connection with it: America’s game,’’ exclaimed poet

Walt Whitman. Baseball, he wrote, ‘‘has the snap, go, fling of the

American atmosphere—belongs as much to our institutions, fits into

them as significantly, as our constitutions, laws: is just as important in

the sum total of our historic life.’’ To preserve this patriotic image,

baseball administrators such as Albert Spalding and A.G. Mills

vehemently dismissed any claims that baseball had evolved from

rounders. In 1905, Mills headed a commission to investigate the

origins of baseball. The group found that baseball was uniquely

American and bore no traceable connection with rounders, ‘‘or any

other foreign sport.’’ Mills traced the game’s genesis to Abner

Doubleday in Cooperstown—a sketchy claim, to be sure, as Mills’

only evidence rested on the recollections of a boyhood friend of

Doubleday who ended his days in an institution for the criminally

insane. Still, Doubleday was a war hero and a man of impeccable

character, and so the commission canonized the late New Yorker as

the founder of baseball, later consecrating ground in his native

Cooperstown for the purpose of establishing the sport’s Hall of Fame.

Baseball’s revered image took a severe hit in 1920, when eight

Chicago White Sox were found to have conspired with gamblers in

fixing the 1919 World Series. The incident horrified fans of the sport

and created distrust and disappointment with the behavior of ballplay-

ers idolized throughout the nation. A young boy, perched outside the

courtroom where the players’ case was heard, summed up the feelings

of a nation when he approached ‘‘Shoeless’’ Joe Jackson, one of the

accused players, and said tearfully, ‘‘Say it ain’t so, Joe.’’ The eight

players were later banned from the sport by baseball commissioner

Kenesaw ‘‘Mountain’’ Landis, but the damage to the sport’s reputa-

tion had already been done.

Baseball successfully weathered the storm created by the ‘‘Black

Sox’’ scandal, as it came to be known, thanks in large part to the

emergence of a new hero who brought the public focus back to the

playing field, capturing the American imagination and generating

excitement of mythic proportions. In the 1920s, George Herman

‘‘Babe’’ Ruth—aptly nicknames the ‘‘Sultan of Swat’’—established

himself as the colossal demigod of sports. With his landmark home

runs and charismatic personality, Ruth triggered a renewed interest in

baseball. While playing for the New York Yankees, Ruth established

single-season as well as career records for home runs. Ruth’s extrava-

gant lifestyle and Paul Bunyan-like appearance made him a national

curiosity, while his flair for drama, which included promising and

delivering home runs for sick children in hospitals, elevated him to

heroic proportions in the public eye. In mythologizing the sport, Ruth

restored and even escalated the sanctity of the ‘‘national pastime’’

that had been diminished by the ‘‘Black Sox’’ scandal. Along with Ty

Cobb, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson, Ruth

gained immortality as a charter member of the Baseball Hall of Fame,

opened in 1939.

By the 1940s, the heroes of the game came to represent an even

more diverse body of the population. Substantial numbers of Italians,

Poles, and Jews inhabited major league rosters, and a host of these

Eastern Europeans became some of the game’s biggest stars. Hank

Greenberg and Joe DiMaggio, among many other children of immi-

grants, became national celebrities for their on-field exploits. In this

respect, baseball served an important socializing function. As the

Sporting News boasted, ‘‘The Mick, the Sheeney, the Wop, the Dutch

and the Chink, the Cuban, the Indian, the Jap, or so the so-called

Anglo-Saxon—his nationality is never a matter of moment if he can

pitch, or hit, or field.’’ During World War II, when teams were

depleted by the war effort, even women became part of baseball

history, as female leagues were established to satisfy the public’s

hunger for the sport. Still, the baseball-as-melting-pot image had one

glaring omission. A ‘‘gentleman’s agreement’’ dating back to the

National Association excluded African Americans from playing

alongside whites in professional baseball. Various so-called Negro

Leagues had formed in the early twentieth century to satisfy the

longings of African Americans to play the game, and a number of

players such as Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige posted accomplish-

ments that rivaled those of white major leaguers. Still, for all their

talent, these players remained barred from major league baseball. In

1947, Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Brach Rickey signed

Jackie Robinson to a major league contract, ostensibly to end segrega-

tion in baseball but also to capitalize on a burgeoning African

American population newly migrated to the cities of the North. When

Robinson played, blacks across the nation were glued to their radios,

cheering him on as a symbol of their own hopes. Robinson was

immensely unpopular with many white fans and players, but his

performance on the field convinced other clubs of the correctness of

Rickey’s decision, and, by 1959, every team in baseball had

been integrated.

The popularity of baseball reached an all-time high in the 1950s.

A new generation of stars, among them Mickey Mantle, Ted Wil-

liams, and Willie Mays, joined Babe Ruth in the pantheon of

American greats. Teams such as the Brooklyn Dodgers, affectionate-

ly known as ‘‘Dem Bums,’’ won their way into the hearts of baseball

fans with their play as well as with indelible personalities such as

‘‘Pee Wee’’ Reese, ‘‘Preacher’’ Roe, and Duke Snider. Baseball

cards, small collectible photographs with player statistics on their flip

sides, became a full-fledged industry, with companies such as Topps

and Bowman capitalizing on boyhood idolatry of their favorite

players. And Yogi Berra, catcher for the New York Yankees, sin-

gle-handedly expanded baseball’s already-sizable contribution to

American speech with such head-scratching baseball idioms as ‘‘It

ain’t over ‘til it’s over.’’ By the end of the twentieth century,

Berra’s witticisms had come to occupy an indelible place in the

American lexicon.

The 1950s witnessed baseball at the height of its popularity and

influence in American culture, but the decade also represented the end

of an era in a sport relatively unchanged since its early days.

Continuing financial success, buoyed especially by rising income

from television and radio rights, led to club movement and league

expansion. In 1953, the Boston Braves transferred its franchise to

Milwaukee, and, five years, later, the New York Giants and Brooklyn

Dodgers moved to California, becoming the San Francisco Giants and

the Los Angeles Dodgers, respectively. Later, new franchises would

emerge in Houston and Montreal. The location of the ballparks in

BASEBALL CARDSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

183

areas geared toward suburban audiences destroyed many urban

community ties to baseball forged over the course of a century.

Players also gained unprecedented power in the latter half of the

twentieth century and, with it, astronomical salaries that did much to

dampen public enthusiasm for their heroes. In 1976, pitchers Andy

Messersmith and Dave McNally challenged the long-established

reserve clause, which owners had, for more than a century, used to

bind players to teams for the duration of their careers. Arbiter Peter

Seitz effectively demolished the clause, ushering in the era of free

agency. For the first time in baseball history, players could peddle

their wares on the open market, and, as a result, salaries skyrocketed.

In 1976, the Boston Red Sox made history by signing Bill Campbell,

baseball’s first free agent, to a four-year, $1 million dollar contract.

The average annual salary rose from $41,000 in 1974 to $1,000,000 in

1992. In 1998, pitcher Kevin Brown signed the first $100 million

contract in sport history, averaging over $13 million per annum. Free

agency, by encouraging the constant movement of players from team

to team, also did much to sever the long-term identification of players

with particular teams and cities, thus further weakening community

bonds with baseball.

Polls consistently revealed that fans resented the overpayment of

players, but still they continued to attend big-league games en masse.

Major league attendance records were broken six times in the 1985

through 1991 seasons. The players’ strike of 1994 dramatically

reversed this tide of goodwill. The players’ rejection of a salary cap

proposed by owners resulted in a 234-day labor stoppage during the

1994 season, with the cancellation of 921 regular-season games as

well as the World Series. The strike, which ended early in the 1995

season, disrupted state and city economies and disappointed millions

of fans. As a result, the 1995 season saw an unprecedented decline in

attendance. The concurrent rise of basketball as a major spectator

sport in the late 1990s also damaged the drawing power of baseball.

Stellar team performances as well as a number of stunning

individual achievements in the latter half of the 1990s brought fans

back to ballparks across the country in record numbers. The Atlanta

Braves, with their remarkable seven divisional titles in the decade,

reminded many of the glory days of baseball, when the New York

Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals registered the word ‘‘dynasty’’ in

the sport’s lexicon. Similarly, the Yankees delivered one of the finest

performances by a team in baseball history, logging 114 victories in

1998 and winning the World Series handily. On the players’ end, Cal

Ripken Jr., in eclipsing Lou Gehrig’s mark of 2,130 consecutive

games played, brought important positive press to baseball in the

wake of its 1994 players’ strike. Ripken’s fortitude and passion for the

game was a welcome relief to fans disillusioned by the image of

selfish players concerned primarily with monetary returns. Similarly,

Baltimore’s Mark McGwire returned the focus of fans to the playing

field with his assault on Roger Maris’ single-season mark for home

runs in 1998. McGwire’s record-setting 70 round-trippers that season

captured the nation’s attention in a Ruth-ian fashion and did much to

restore the mythos and romance of the sport, much as the Sultan of

Swat’s accomplishments had done in the 1920s.

Though professional baseball has had its moments of honor and

of ignominy, perhaps the real legacy of the glory days of baseball is

still to be found on community playing fields. Baseball is not only

beloved as a spectator sport, but is still often the first team game

played by both sexes in peewee and little leagues. While modern

mothers may shudder to imagine their children imitating the tobacco-

chewing ballplayers they see on television, there is an undeniable

thrill at the little leaguer’s first home run that harks back to the most

truly electrifying quality of baseball—that moment when skill meets

desire, enabling the ordinary person to perform magnificent feats.

—Scott Tribble

F

URTHER READING:

Creamer, Robert. Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. New York, Simon

and Schuster, 1974.

Goldstein, Warren. Playing for Keeps: The History of Early Baseball.

Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1989.

Rader, Benjamin. Baseball: A History of America’s Game. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Early Years. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1960.

Voigt, David. American Baseball. Norman, University of Oklahoma

Press, 1966.

Baseball Cards

Bought and traded by the youth of America who wanted to see

their favorite players and exchange the cards with other young fans,

baseball cards were a symbol of bubble gum hero worship and

youthful innocence during the first three-quarters of the twentieth

century. Serious collectibles only since about 1975, baseball card

collecting has turned into a multimillion-dollar business, a transfor-

mation to commercial and financial enterprise.

The first baseball cards were a far cry from the high-tech,

colorful prints of today. The Old Judge Company issued the first

series of cards in 1887. They were distributed in cigarette packages

and consisted of player photographs mounted on stiff cardboard.

Those ‘‘Old Judges,’’ produced until 1890, are treasured parts of

many current collections. Included in those sets was one of the most

valuable cards in the history of collecting—the Honus Wagner

baseball card. According to legend, Wagner, a nonsmoker, was irate

when he discovered his picture being used to promote smoking. As a

result, he ordered his likeness removed from the set. Today, it appears

there are no more than twenty-five Wagner cards in existence, each

worth nearly one hundred thousand dollars.

By the 1920s, tobacco companies had given way to gum and

confectionery enterprises as the prime distributors of baseball cards.

Goudey Gum Company, a leading baseball card manufacturer, issued

sets of baseball cards from 1933 to 1941. Goudey’s attractive designs,

with full-color line drawings on thick card stock, greatly influenced

other cards issued during that era. Some of the most attractive and

collectible cards were released in the two decades preceding

World War II.

The war brought an abrupt end to the manufacture and collection

of baseball cards because of the serious shortages of paper and rubber.

Production was renewed in 1948 when the Bowman Gum Company

issued a set of black-and-white prints with one card and one slab of

gum in every penny pack. That same year, the Leaf Company of

Chicago issued a set of colorized picture cards with bubble gum. Then

in 1951, Topps Gum Company began issuing cards and became the

undisputed leader in the manufacture of baseball cards, dominating

BASIE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

184

Dizzy Dean’s 1934 baseball card.

the market for the next three decades. The Topps 1952 series set the

standard for baseball cards by printing individual statistics, personal

information, team logos, and large, clear, color pictures. There were

continuing legal squabbles over who held the rights to players’

pictures. With competition fierce during the 1950s, Topps finally

bought out the Bowman Company.

It was not until the mid-1970s that the card collecting business

began in earnest. One card collector stated that in 1972, there were

only about ten card dealers in the New York area who would meet on

Friday nights. No money ever changed hands—it was strictly trading.

But several years later, the hobby began to grow. As more and more

people began buying old cards, probably as a link to their youth,

prices rose, and small trading meetings turned into major baseball

card conventions at hotels and conference centers. By the end of the

twentieth century, there are baseball card conventions, shows, and

flea markets in nearly all major cities.

In the 1980s, various court decisions paved the way for other

companies to challenge Topps’s virtual monopoly. Fleer, Donruss,

and Upper Deck issued attractive and colorful cards during the 1980s,

although bubble gum was discarded as part of that package. In the

1990s, other companies followed: Leaf, Studio, Ultra, Stadium Club,

Bowman, and Pinnacle. With competition fierce, these companies

began offering ‘‘inserts’’ or special cards that would be issued as

limited editions in order to keep their prices high for collectors.

However, these special sets began driving many single-player collec-

tors out of the hobby. Average prices of cards were rising to

unprecedented heights while the number of cards per pack was dropping.

—David E. Woodard

F

URTHER READING:

Beckett, James. The Official 1999 Price Guide to Baseball Cards.

18th ed. New York, Ballantine Publishing, House of

Collectibles, 1998.

Green, Paul. The Complete Price Guide to Baseball Cards Worth

Collecting. Lincolnwood, Illinois, NTC/Contemporary Publish-

ing, 1994.

Larsen, Mark. Complete Guide to Baseball Memorabilia. 3rd ed. Iola,

Wisconsin, Krause Publications, 1996.

Lemke, Bob, and Robert Lemke, eds. 1999 Standard Catalogue of

Baseball Cards. 8th ed. Iola, Wisconsin, Krause Publishers, 1998.

Pearlman, Dan. Collecting Baseball Cards: How to Buy Them, Store

Them, Trade Them, and Keep Track of Their Value as Invest-

ments. 3rd ed. Chicago, Bonus Books, 1991.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, eds. Total Baseball. 2nd ed. New York,

Warner Books, 1991.

Basie, Count (1904-1984)

One of the most imitated piano players, Count Basie brought a

minimalist, subtle style to his powerful work at the keyboard and was

the driving force behind a star-studded band that influenced the

course of jazz during the big band era of the late 1930s and early

1940s. Its style of interspersing the Count’s intricately timed piano

chords with blasting ensemble passages and explosive solos made it

one of the most admired of big bands for more than 30 years.

By sheer accident, Basie came under the influence of the Kansas

City jazz style, the essence of which was ‘‘relaxation.’’ Franklin

Driggs writes that the ‘‘Southwestern style’’ had ‘‘intense drive and

yet was relaxed.’’ Notes might be played ‘‘just before or just after’’

the beat while the rhythm flowed on evenly. These are characteristics

any listener to Basie’s ‘‘One O’Clock Jump’’ would understand. At

age 24, Basie was stranded in Kansas City when a vaudeville act he

accompanied disbanded. Born William James Basie in Red Bank,

New Jersey, he had become interested in jazz and ragtime in the New

York area and had studied briefly with Fats Waller. Adrift in Kansas

City, he played background to silent movies and then spent a year

with Walter Page’s Blue Devils, a band that included blues singer

Jimmy Rushing, whose career would merge with the Count’s.

The Blue Devils disbanded in 1929, and Basie and some of the

other members joined bandleader Bennie Moten, who had recorded

his Kansas City-style jazz on Okeh Records. After Moten died in

1935, Basie took the best of his jazzmen and started a band of his own.

Basie gradually upgraded the quality of his personnel, and when jazz

critic John Hammond happened to hear the band on a Kansas City

radio station, he persuaded Basie to bring the band to New York in

BASIEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

185

Count Basie

1936. He recorded his first sides for Decca in January, 1937, and

within a year the band’s fame was becoming international.

There were a number of distinctive qualities about the Basie

band other than the Count’s unique piano style. The rhythm section—

featuring Jo Jones, drums, Walter Page, bass, and Freddie Greene,

guitar—was widely admired for its lightness, precision, and relaxed

swing. Jimmy Rushing’s alternatively virile and sensitive style of

blues singing on such band numbers as ‘‘Sent for You Yesterday

(Here You Come Today)’’ and ‘‘Goin’ to Chicago’’ were longstanding

hits. The Count recruited a bandstand-full of outstanding side men,

whose solo improvisations took the band to ever higher plateaus.

They included Lester Young and Herschel Evans on tenor sax, Earl

Warren on alto, Buck Clayton and Harry Edison on trumpets, and

Benny Morton and Dickie Wells on trombone. The band’s chief

arranger was Eddie Durham, but various members of the band made

contributions to so-called ‘‘head’’ arrangements, which were infor-

mally worked out as a group and then memorized.

The soul of Count Basie’s music was the blues, played in a style

described by Stanley Dance as ‘‘slow and moody, rocking at an easy

dancing pace, or jumping at passionate up-tempos.’’ Most of the

band’s greatest successes have been blues based, including ‘‘One

O’Clock Jump’’ and numbers featuring the vocals of Jimmy Rushing.

Woody Herman, whose first band was known as ‘‘The Band That

Plays the Blues,’’ was strongly influenced by the Basie sound.

In the 1950s, Basie and his band toured Europe frequently, with

great success. During his second tour of Britain, in the fall of 1957, his

became the first American band to play a command performance for

the Queen. He set another precedent that fall by playing 13 weeks at

the roof ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel as the first African

American jazz orchestra to play that prestigious venue.

During his long tenure at the head of a band that appealed to a

wide variety of fans—both the jazz buffs and the uninitiated—

swing music was becoming increasingly complex, rhythmically and

harmonically, but Basie had no interest in the be-bop craze. George

Simon writes that the Basie band ‘‘continued to blow and boom in the

same sort of simple, swinging, straight-ahead groove in which it has

slid out of Kansas City in the mid-1930s.’’ He adds that the Count

‘‘displayed an uncanny sense of just how far to go in tempo, in

volume, and in harmonic complexity.’’

Stanley Dance summed it up when he wrote in 1980 about the

importance of Basie’s ‘‘influence upon the whole course of jazz. By

BASKETBALL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

186

keeping it simple and sincere, and swinging at all times, his music

provided a guiding light in the chaos of the past two decades.’’

—Benjamin Griffith

F

URTHER READING:

Basie, Count, as told to Albert Murray. Good Morning Blues: The

Autobiography of Count Basie.New York, Random House, 1985.

Dance, Stanley. The World of Count Basie. New York, Scribner’s, 1980.

Driggs, Franklin S. ‘‘Kansas City and the Southwest.’’ Jazz. Edited

by Nat Hentoff and Albert J. McCarthy. New York, Da Capo

Press, 1974.

Simon, George T. The Big Bands. New York, MacMillan, 1974.

Basketball

The sport of basketball was invented at the close of the nine-

teenth century. By the end of the twentieth century, only soccer

surpassed it as the world’s most popular sport, as top basketball

players from the United States were among the most recognized

people on Earth.

Basketball was invented in late 1891 by Dr. James A. Naismith,

physical education director at the Young Men’s Christian Association

(YMCA) in Springfield, Massachusetts. The YMCA students were

tiring of standard calisthenics and demanded a new, team sport to be

played indoors between the end of football season in autumn and the

start of baseball season in the spring. Naismith hit upon the idea of

two teams of players maneuvering a ball across a gymnasium towards

a set target. He obtained a pair of peach baskets—he originally

wanted to use boxes—and nailed them on beams on either end of the

gym. The first game ever played resulted in a 1-0 score, with one

William R. Chase scoring the lone point with a soccer ball; Naismith

and his players quickly realized that the new sport had potential.

Naismith resisted efforts to name his invention ‘‘Naismith-

ball,’’ preferring ‘‘basket ball’’ instead. He wrote an article describ-

ing the sport in his YMCA’s magazine in early 1892, and YMCAs

across the country and around the world picked up on the sport during

the 1890s. By 1895 Naismith had set up standard rules: five players on

each team, with successful shots counting two points each. Eventual-

ly, players who were fouled by opponents would be able to make

‘‘free throws,’’ counting one point each, shooting a short distance

from the basket.

Within weeks of Naismith’s first game, women athletes in

Springfield were also playing basketball, and the first intercollegiate

college basketball game, in fact, was between the Stanford women’s

team and the University of California women’s squad in April 1895.

Within a year the University of Chicago beat the University of Iowa,

15-12, in the first men’s college basketball game. By the first decade

of the twentieth century, many colleges were fielding men’s and

women’s basketball teams. Men’s college basketball exploded in

popularity during the 1930s, with heavily promoted doubleheaders at

New York’s Madison Square Garden featuring the top teams in the

country before packed audiences.

The first successful professional basketball team was the Origi-

nal Celtics, which were formed in New York before World War I. The

team of New Yorkers generally won 90 percent of their games against

amateur and town teams, and had a record of 204 wins against only 11

defeats in the 1922-1923 season. In 1927, white promoter Abe

Saperstein started the Harlem Globetrotters, a barnstorming basket-

ball team made up of blacks (when most college and pro teams had no

African American players). They became best known for their

irreverent on-court antics and their theme song, the jazz standard

‘‘Sweet Georgia Brown.’’

The scores of basketball games prior to the 1940s seem shock-

ingly low today, as teams rarely scored more than 40 points a game. It

was customary in early basketball for players to shoot the ball with

both hands. Once the one-hand jump shot, popularized by Stanford

star Hank Lusietti, gained acceptance in 1940, players were more

confident in taking shots, and scoring began to increase.

Professional basketball leagues began and folded many times in

basketball’s infancy. By the end of World War II, there were two

leagues competing for top college prospects, the National Basketball

League and the Basketball Association of America. The two leagues

merged in 1949, forming the National Basketball Association (NBA).

The NBA’s first star was the first great basketball tall-man, George

Mikan. Improbable as it seems now, players over six feet in height

were once considered to make bad basketball players, seen as

ungainly and uncoordinated. The 6’ 10’’ Mikan, who had starred as a

collegian for DePaul University, erased this stereotype single-handedly,

winning five NBA scoring titles as his Minneapolis (later Los

Angeles) Lakers won four NBA championships. In a poll of sports-

writers in 1950, Mikan was named ‘‘Mr. Basketball’’ for the first 50

years of the twentieth century.

As Mikan starred in the professional ranks, college basketball

was shaken to the core by revelations of corruption. In 1951 the New

York district attorney’s office found that players at many of the top

schools had agreed to play less than their best—to ‘‘shave points’’—

in exchange for gambler’s money. The accused players frequently

met gamblers during summers while working and playing basketball

in New York’s glamorous Catskills resort areas. Players from the City

College of New York, which had won both the National Invitational

Tournament and the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Associa-

tion) basketball finals in 1951, were implicated, as were stars from

Long Island University, coached by popular author Clair Bee. The

image of top players testifying to grand juries would stain college

basketball for the rest of the decade.

Basketball had been marked by stalling tactics, where one team

would possess the ball for minutes at a time without shooting or

scoring. In 1954, the NBA adopted a shot clock, requiring that a team

shoot the ball within 24 seconds of gaining possession (College

basketball would wait until 1985 before mandating a similar shot

clock). This one rule resulted in an outburst of scoring, which helped

push professional basketball attendance up in the 1950s. Fans of the

era flocked to see the Boston Celtics. Led first by guard Bob Cousy,

and later by center Bill Russell, the Celtics won eight straight NBA

titles from 1959 through 1966. Their arch-nemesis was center Wilt

Chamberlain of the Philadelphia Warriors and 76ers. The most

dominant scorer in NBA history, Chamberlain averaged 50 points for

the 1961-1962 season, including his memorable performance on

March 2, 1962, where he scored 100 points. Chamberlain outperformed

Bill Russell during Boston-Philadelphia matchups, but the Celtics

almost inevitably won the titles.

As the Celtics were the NBA’s dynasty in the 1960s, so were the

UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Bruins college basket-

ball’s team to beat in the 1960s and 1970s. Coached by the soft-

spoken, understated John Wooden, the UCLA Bruins won nine

BASKETBALLENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

187

NCAA tournament titles in one ten-year span, including seven

straight from 1967 to 1973. Wooden’s talent during this time included

guards Walt Hazzard and Gail Goodrich, and centers Lew Alcindor

(who would change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and Bill

Walton. During one stretch encompassing three seasons, UCLA won

an improbable 88 consecutive games, an NCAA record.

The NBA found a new rival in 1967, with the creation of the

American Basketball Association (ABA). The new league adopted a

red, white, and blue basketball and established a line some 20 feet

from the basket, beyond which a field goal counted for three points.

The three-point line and the colored ball made the ABA something of

a laughingstock to basketball traditionalists, and ABA attendance and

media coverage indeed lagged behind the NBA’s. But by the early

1970s, the ABA had successfully signed several top college picks

from under the NBA’s nose, and its top attraction was Julius Erving of

the Virginia Squires and New York Nets. Erving, nicknamed ‘‘Dr. J,’’

turned the slam-dunk into an art form, hanging in the air indefinitely,

virtually at will. Erving was definitely the hottest young basketball

talent in either league. In 1976 the NBA agreed to a merger, and four

ABA teams joined the NBA. Erving signed a $6 million contract with

Philadelphia. In the first All-Star game after the merger, five of the 10

NBA All-Star players had ABA roots.

The merger, however, was not enough to stem the NBA’s

declining attendance and fan interest. People were not only not

following professional basketball in the 1970s, they seemed actively

hostile to it. The perception of pro basketball as being dominated by

black athletes, some felt, prevented the sport from commanding

television revenue and advertising endorsements. According to one

disputed report in the late 1970s, fully three-quarters of NBA players

were addicted to drugs. Once again, the NBA found its salvation in the

college ranks. In 1979 Michigan State, with star guard Earvin

‘‘Magic’’ Johnson, defeated Indiana State, and star forward Larry

Bird, for the NCAA basketball title. The game drew a record

television audience, and helped popularize the NCAA basketball

tournament, later known as ‘‘March Madness.’’ The tournament

eventually included 64 teams each season, with underdog, ‘‘Cinderel-

la’’ teams such as North Carolina State in 1983 and Villanova in 1985

emerging to win the championship. By the 1990s, the tournament

spawned hundreds of millions of dollars in office pools and Vegas

gambling, as cities vied to host the ‘‘Final Four,’’ where the four

remaining teams would compete in the semifinals and championship

game. Even the official start of college basketball practice in the fall

became a commercialized ritual, as schools hosted ‘‘Midnight Mad-

ness’’ events, inviting fans to count the minutes until midnight of the

first sanctioned day college teams could practice.

In the fall of 1979 Bird had joined the Boston Celtics and

Johnson the Los Angeles Lakers. Johnson led the Lakers to the 1980

NBA title, playing every position in the deciding championship game

and scoring 42 points. Bird and Johnson would usher in a new era in

the NBA—Bird, with his tactical defense and Johnson with his

exuberant offense (the Lakers’ offensive strategy would be called

‘‘Showtime’’). The Celtics and Lakers won eight NBA titles in the

1980s, as Bird and Johnson reprised their 1979 NCAA performance

by going head-to-head in three NBA finals.

The success of the NBA created by Bird and Johnson during the

1980s rose to an even greater level during the 1990s, due in no small

measure to Michael Jordan. The guard joined the Chicago Bulls in

1984, having played three seasons at the University of North Caroli-

na; as a collegian, Jordan had been on an NCAA championship team

and the 1984 gold medal United States Olympic squad. Jordan

immediately established himself as a marquee NBA player in his first

seasons, scoring a playoff record 63 points in one 1986 post-season

game. His dunks surpassed even Erving’s in their artistry, and Jordan

developed a remarkable inside game to complement that. Slowly, a

great Bulls team formed around him, and Jordan led the Bulls to three

straight NBA titles in 1991-1993. Jordan then abruptly left basketball

for 16 months to pursue a major league baseball career. A chagrined

Jordan returned to the Bulls in February 1995, and in his final three

complete seasons the Bulls won three more consecutive champion-

ships. The 1996 Bulls team went 72-10 in the regular season, and

many experts consider this team, led by Jordan, Scottie Pippen,

Dennis Rodman, and Toni Kukoc, to be the finest in NBA history.

Jordan retired for good after the 1997-1998 season; his last shot in the

NBA, in the closing seconds of the deciding championship game

against Utah in June 1998, was the winning basket. Jordan’s an-

nouncement of his retirement in January 1999 received media cover-

age usually reserved for presidential impeachments and state funerals.

Though the United States had been the birthplace of basketball,

by the end of the twentieth century America had to recognize the

emergence of international talent. The Summer Olympics introduced

basketball as a medal sport in 1936, and the United States won gold

medals in its first seven Olympics, winning 63 consecutive games

before losing the 1972 Munich gold medal game, 50-49, to the Soviet

Union on a controversial referee’s call. After the United States lost in

the 1988 Olympics, the International Olympic Committee changed its

rules to allow the United States to assemble a team made up not of

amateurs, but of NBA stars. The ‘‘Dream Team’’ for the 1992

Barcelona Games was, some insisted, the greatest all-star team ever,

in any sport. The squad featured Larry Bird, Magic Johnson (who had

retired from the NBA in 1991 after testing positive for the HIV virus),

Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley, Patrick Ewing, Karl Malone, and

David Robinson. The United States team crushed its opponents,

frequently by margins of 50 points a game. Many of the Dream Team

opponents eagerly waited, after being defeated, to get the American

stars’ autographs and pictures. The 1992 squad easily won a gold

medal, as did a professional United States team in the 1996 Atlanta

Olympics (whose stars included Grant Hill, Scottie Pippen, and

Shaquille O’Neal).

The 1990s also saw an explosion of interest of women’s basket-

ball, on professional as well as collegiate levels. Many credit this

popularity with the enforcement of Title IX, a 1971 federal statute

requiring high schools and colleges to fund women’s sports programs

on an equal basis with men’s. The top college team of the time was

Tennessee, which won three straight women’s NCAA titles in 1996-

1998, narrowly missing a fourth in 1999. In 1996, a women’s

professional league, the American Basketball League (ABL) was

inaugurated, followed a year later by the Women’s National Basket-

ball Association (WNBA), an offshoot of the NBA. The ABL folded

in 1999, but the WNBA, which held its season during the summer-

time, showed genuine promise; its stars included Rebecca Lobo of the

New York Liberty (she had starred at the University of Connecticut)

and Cynthia Cooper of the Houston Comets, which won the first two

WNBA championships. Women’s basketball was characterized less

by dunks and flamboyant moves, and more by fundamental offense

and defense. John Wooden, for one, said he generally preferred

watching women’s basketball to men’s. College and pro women’s

games were known, in fact, for having a strong male fan base, as well

as entire families in attendance.

BATHHOUSES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

188

As the twentieth century closed, the NBA proved it was no

longer immune to the pressures of American professional sports. As

major league baseball and the National Football League had suffered

through lengthy and devastating strikes during the 1980s and 1990s,

the NBA had its first-ever work stoppage in the fall of 1998. NBA

team owners locked players out in October, declaring the collective

bargaining agreement with the player’s union null and void. At issue

was the league salary cap; each team had been previously allowed to

exceed the cap for one player (in Chicago’s case, for Michael Jordan),

but the owners wanted to abolish this exception. The players stead-

fastly refused, and the first half of the 1998-1999 season was lost.

Both sides reached an agreement in early 1999, and the regular season

began three months late, on February 6. To the surprise of players and

owners alike, the NBA lockout garnered little attention from the fans.

Basketball slowly entered other elements of American popular

culture during the latter part of the twentieth century. ‘‘Rabbit’’

Angstrom, the middle-aged hero of four John Updike novels, had

been a star basketball player in high school. Jason Miller’s Pulitzer-

Prize winning play That Championship Season (1972) reunited

disillusioned, bitter ex-jocks on the anniversary of their state high

school title victory. One of the most acclaimed documentaries of the

1990s, Hoop Dreams (1994), tracked two talented Chicago ghetto

basketball players through their four years of high school, each with

an eye towards a college scholarship and an NBA career. Novelist

John Edgar Wideman, who had played basketball at the University of

Pennsylvania during the 1960s, often used the game metaphorically

in his award-winning fiction (his daughter Jamila was a star player at

Stanford, and later the WNBA). Wideman’s teammate at Oxford

University while on a Rhodes Scholarship was Bill Bradley, who

played for Princeton, and later had a Hall of Fame professional career

with the Knicks. Bradley served three terms in the United States

Senate, and wrote a bestselling book defining basketball’s qualities

(Values of the Game) as he prepared a presidential campaign for the

year 2000.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Decourcy, Mike. Inside Basketball: From the Playgrounds to the

NBA. New York, MetroBooks, 1996.

Dickey, Glenn. The History of Professional Basketball since 1896.

New York, Stein and Day, 1982.

Douchant, Mike, editor. Encyclopedia of College Basketball. Detroit,

Gale Research, 1995.

Fox, Stephen R. Big Leagues: Professional Baseball, Football, and

Basketball in National Memory. New York, Morrow, 1994.

George, Nelson. Elevating the Game: Black Men and Basketball.

New York, HarperCollins, 1992.

Koppett, Leonard. The Essence of the Game Is Deception. Boston,

Little Brown & Company, 1973.

McCallum, John D. College Basketball, U.S.A., since 1892. New

York, Stein and Day, 1978.

Peterson, Robert. Cages to Jump Shots: Pro Basketball’s Early Years.

New York, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Pluto, Terry. Loose Balls. New York, Fireside, 1991.

———. Tall Tales. New York, Fireside, 1994.

Sachare, Alex, editor. The Official NBA Basketball Encyclopedia.

New York, Villard, 1994.

Bathhouses

In many cultures, bathing in communal bathhouses has been an

important social and even religious ritual. In Japan it is the sento,

among Yiddish-speaking Jews, the shvitz, and in the Arab world the

hammam, all of them centers for socializing across class lines,

providing relief from culturally imposed modesty, and a place to get

luxuriously clean. By the early 1900s, New York City had built and

maintained a network of public bathhouses—many of them resem-

bling Roman temples—in immigrant neighborhoods. Because they

are traditionally segregated by gender, bathhouses have also long

been associated with same-sex eroticism. It is in this capacity that

they have gained most of their notoriety in American culture. Though

the increasing availability of indoor plumbing in private houses

decreased the need for public baths, the bathhouse remained a

mainstay of American gay male culture until the advent of the AIDS

epidemic in the mid-1980s. One of the most prominent of these

venues was the Club Baths chain, a nationwide members-only net-

work that permitted access to facilities across the country. Most of the

Club bathhouses offered clean but spartan accommodations (a cubicle

with a mattress pad or locker for personal items, and a fresh towel) for

about $10 for an eight-hour stay.

Even before the reconstruction of a ‘‘gay’’ identity from the

1960s, the baths had achieved some degree of fame as male-only

enclaves: witness the depiction in films of businessmen, spies, or

gangsters meeting in a Turkish bath, protected only by a towel around

the waist. The Turkish baths of yore were part social club, part night

club, and part sex club. They often had areas called ‘‘orgy rooms’’

where immediate and anonymous sex was available. The decade of

the 1970s, after the beginning of gay liberation, was the ‘‘golden age’’

of the gay bathhouse. Gay male culture became chic, and these

gathering places became celebrity ‘‘hot spots.’’ The most famous of

them was the Continental Baths on Manhattan’s Upper West Side,

where Bette Midler launched her career singing to an audience of

towel-clad men. In the intoxicating years that followed the Stonewall

riots of 1969, gay men reveled in their new visibility, with bathhouses

emerging as carnal theme parks that became self-contained fantasy

worlds for erotic play, though it is not clear how many of the patrons

identified themselves as ‘‘gay,’’ since the focus was on ‘‘men having

sex with men,’’ not on socially constructed identities. It was not

uncommon for bathhouse patrons to include married ‘‘straight’’ men

taking a break from domestic obligations in orgy rooms packed full of

writhing bodies, or in private rooms for individual encounters. Gay or

straight, customers hoped to find in the baths a passport to intense

male pleasure in an environment that fairly throbbed with Dionysian

energy. One large bathhouse in San Francisco boasted that it could

serve up to eight hundred customers at a time. The St. Marks Baths in

New York’s East Village attracted customers from around the world

with its sleek, modernistic facilities that were a far cry from the

dumpy barracks of earlier decades, like the Everard Baths farther

uptown, once the site of a church. The Beacon Baths in midtown

Manhattan adjoined a cloistered convent, and it has long been

rumored that the bathhouse once borrowed fresh towels from the nuns

when its supply ran short.