Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BEAVIS AND BUTTHEADENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

209

Goldman, William. ‘‘Part 3: The Miss America Contest or ‘Do You

Take Preparation H?’’’ Hype and Glory. New York, Villard

Books, 1990, 189-298.

Morgan, Robin. ‘‘Women vs. the Miss America Pageant (1968).’’

The Word of a Woman: Feminist Dispatches 1968-1992. New

York, W. W. Norton & Co., 1992, 21-29.

Prewitt, Cheryl, with Kathryn Slattery. A Bright Shining Place.

Garden City, New York, Doubleday-Galilee, 1981.

Savage, Candace. Beauty Queens: A Playful History. New York,

Abbeville Press, 1998.

Beavers, Louise (1902-1962)

Louise Beavers, whose first film role was as a slave in the silent

version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927), was cast as the happily devoted

black servant during most of her career. However, she broke out of

that type of role in Imitation of Life (1934) in her moving portrayal of

the heartsick Aunt Delilah, whose light-skinned daughter denied her

mother to ‘‘pass’’ as white. Even after this critically praised perform-

ance, Beavers returned to the limited servant-type character roles

available to black actors during this period.

Beavers later moved to television and replaced Ethel Waters as

the star of Beulah (1950-1953), the managing maid to the inept

Hendersons, during its final season. The series gave Beavers star

billing. However, she tired of the pace and stereotypical role and left

the series while it was still popular.

—Denise Lowe

F

URTHER READING:

Hill, George. Black Women in Television. New York, Garland Pub-

lishing, 1990.

MacDonald, J. Fred. Blacks and White TV. Chicago, Nelson-Hall

Publishers, 1992.

Beavis and Butthead

MTV’s breakthrough hit of the 1990s, Beavis and Butthead,

grew out of a series of animated shorts. Each half-hour episode

chronicled the title characters’ hormone-driven adventures while

offering their commentary on popular music videos. Beavis and

Butthead were almost universally-recognized pop icons by the time

their run on MTV ended in 1997. They helped to usher in a new genre

of irreverent television comedy and symbolized for many critics the

decay of the American mind in the days of Generation X.

Those viewing ‘‘Frog Baseball,’’ Beavis and Butthead’s pre-

miere installment on MTV’s animation showcase Liquid TV, might

have judged the cartoon—in which the duo does indeed play our

national pastime with a frog as the ball—nothing more than a

demented teenage doodle. But creator Mike Judge’s simplistically-

rendered protagonists struck some chord with MTV’s young audi-

ence, and more episodes were featured. Beavis and Butthead’s

appearance on the 1992 Video Music Awards marked a coming-out of

sorts, and Judge and his creations were offered a weekly spot on the

cable network in 1993. Including videos layered with the boys’

comments from the couch was the network’s idea. The Beavis and

Butthead Experience, an album featuring the two heroes collaborat-

ing with several of their favorite artists, was released late in 1993.

Beavis and Butthead were guests several times on Late Night with

David Letterman and were a featured act at the 1994 Super Bowl

halftime show. Judge’s cartoon creations were becoming important

Hollywood personalities in an age that demanded celebrities who

could wield power in several media. The culmination of this process

was the release of their 1996 movie, Beavis and Butthead Do

America, in which they embark on a cross-country quest for their

lost television.

Beavis and Butthead’s rise to stardom was not without its

wrinkles. The show was sued in late 1993, while their popularity

surged, by an Ohio mother who claimed Beavis’s repeated maniacal

calls of ‘‘Fire! Fire!’’ had encouraged her son to set a fire in their

trailer home that claimed the life of his older sister. As part of the

settlement, all references to fire have been edited from old and new

episodes of the show. Judge and MTV parted ways amicably in 1997,

after 220 episodes. Judge continued creating animated shows for

adults. Beavis and Butthead, despite their best efforts to do nothing,

had irrevocably altered the fields of animation, comedy, and teen

culture as a whole. Taboos had been broken. Crudity had soared to

new heights.

On the surface, Beavis and Butthead is a celebration of the

frustrated male adolescent sex drive. Butthead, the dominant member

of the team, is described in his own Beavis and Butthead Ensucklopedia

as ‘‘ . . . pretty cool. He hangs out a lot and watches TV. Or else he

cruises for chicks . . . he just keeps changing the channels, and when a

hot chick comes on he’ll check out her thingies.’’ Butthead’s off-

center whipping boy Beavis is, in comparison, ‘‘ . . . a poet, a

storyteller, a wuss, a fartknocker, a dillweed, a doorstop and a paper

weight.’’ The show established and maintained its fan base with

storylines about escape (from the law, social norms, or teenage

boredom) and desire (for women, recognition, or some new stimulus).

Judge’s vignettes, peppered with Beavis’ nerdy snicker and Butthead’s

brain dead ‘‘Huh. Huh-huh,’’ left no subject as sacred, from God and

school to death itself. They destroyed public and private property,

dodged responsibilities, let the world wash through the television and

over them on their threadbare couch, and bragged about their fanta-

sies of exploiting women. Critics and would-be censors were quick to

point to the show as evidence of the current generation’s desensitization

to modern social issues and general dumbing-down. Beavis and

Butthead, many said, were evidence enough that the current crop of

kids were not ready to take over. ‘‘I hate words,’’ snorts Beavis while

a music video flashes superimposed phrases on the screen. ‘‘Words

suck. If I wanted to read, I’d go to school.’’

But Beavis and Butthead’s innocent absorption of America’s

mass media and their simultaneous applause and ridicule of popular

culture spoke to ‘‘Gen X’’ on some level. And deep in their observa-

tions were occasional gems of world-weary wisdom. ‘‘The future

sucks,’’ insists Beavis in one episode, ‘‘change it!’’ Butthead replies,

‘‘I’m pretty cool Beavis, but I cannot change the future.’’

—Colby Vargas

F

URTHER READING:

Judge, Mike, et al. The Beavis and Butthead Ensucklopedia. New

York, MTV Pocket Books, 1994.

BEE GEES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

210

The Bee Gees

The Australian Brothers Gibb, Barry and twins Robin and

Maurice (1949—), are one of the most successful, versatile, enduring

recording groups in the world. Their trademark close harmonies,

along with their remarkable songwriting abilities and talent for

creating distinctive melodies, have earned them dozens of top 40 hits,

including six consecutive number ones from 1977-79. Because of

their involvement with the soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever, they

are primarily artistically associated with late-1970s disco excesses.

However, they released their first widely available record in 1967,

and began a string of hits in several genres: pop, psychedelic, country,

R&B, and soul. Though they still regularly top the charts in other parts

of the world, they have not had major chart success in the United

States since 1983. In 1997, the Bee Gees were inducted into the

Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

—Joyce Linehan

F

URTHER READING:

Bee Gees. Bee Gees Anthology: Tales from the Brothers Gibb a

History in Song 1967-1990. Hal Leonard Publishing Corpora-

tion, 1991.

Beer

Given Americans’ love of beer, one might be tempted to call it

America’s drink. In truth it is the world’s drink. Originating in ancient

Babylon, and passed on in various regional variations for thousands

of years, beer is made in virtually every country in the world.

Throughout Europe, but especially in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and

the United Kingdom, the public house or alehouse serving locally-

brewed beer has been an institution for hundreds of years. In Belgium,

Trappist monks have been producing their distinctive beers since the

eleventh century. But it wasn’t until the twentieth century that beer

was subjected to the peculiar modernizing effects of American mass

culture. Mass-produced, packaged, and advertised everywhere, Ameri-

can lager beer in its various similar-tasting brands—Budweiser,

Miller, Strohs, Coors, Pabst, etc.—became the drink of the masses. In

1995, American brewers produced 185 million barrels of beer, 176

million of which were consumed in the United States. The vast

majority of the beer produced in the United States—over 95 per-

cent—is produced by the major brewers, Anheuser-Busch, Miller,

Strohs, Heileman, Coors, and Pabst. However, craft brewers have

kept ancient brewing traditions alive and in the 1990s offer their

microbrews to a growing number of beer drinkers looking for an

alternative to mass-produced fare.

It is no exaggeration to say that beer came to America with the

first colonists. Indeed, there is evidence that suggests that one of the

main reasons the Mayflower stopped at Plymouth Rock in 1620 was

that they were running out of beer. Had they made it to New

Amsterdam they might have replenished their stock with ales made by

the Dutch settlers who had been brewing beer there since 1612. The

first commercial brewery opened in New Amsterdam in 1632 and as

the colonies expanded many a small community boasted of a local

brewer. But the failure of colonists to grow quality barley (a key

ingredient in beer) and the easy availability of imported English beer

slowed the development of an indigenous brewing industry. As

tensions between the colonies and England increased in the eight-

eenth century, beer became one of a number of British goods that

were no longer wanted by colonists eager to declare their indepen-

dence. By 1770, George Washington and Patrick Henry were among

the many revolutionaries who called for a boycott of English beer and

promoted the growth of domestic brewing. Some of the first legisla-

tion passed by the fledgling United States limited the taxes on beer to

encourage such growth. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin

both supported a plan to create a state-supported national brewery (the

plan came to naught.)

The nineteenth century saw a tremendous growth in brewing in

America. Immigrants from the ‘‘beer belt’’ countries of Europe—

Ireland, Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and The Netherlands—

brought their brewing knowledge and love of beer to many American

communities, and by 1840 there were over 140 breweries operating in

the United States. In that same year America was introduced to lager

beer by a Bavarian brewer named Johann Wagner. Little did he know

that he had introduced the future of American brewing. Prior to 1840,

the beers produced in America were all ales, defined by their use of a

top-fermenting yeast and aged and served at room temperature.

Lagers—which used a bottom-fermenting yeast and required cold

storage—tended to be mellower, smoother, and cleaner tasting, and

they soon found an audience, especially when Bohemian brewers

developed the Pilsner style, the lightest, clearest lager made. Milwau-

kee, Wisconsin—with its proximity to grain producers, its supply of

fresh water, and its large German population—soon became the

capital of American brewing. The Pabst, Schlitz, and Miller Brewing

companies all trace their roots to nineteenth-century Milwaukee. In

fact, Schlitz claimed for many years to the ‘‘beer that made

Milwaukee famous.’’

Milwaukee was not alone in embracing beer, especially lager

beer. By 1873 there were over 4,131 breweries operating in the United

States and they produced nine million barrels of beer, according to

Bill Yenne in Beers of North America. Most of the twentieth century’s

major brewers got their start in the late nineteenth-century boom in

American brewing, including Anheuser-Busch (founded in 1852), the

Miller Brewing Company (1850), the Stroh Brewery Company

(1850), the G. Heileman Brewing Company (1858), the Adolph

Coors Company (1873), and the Pabst Brewing Company (1844).

Adolphus Busch, who some hail as the first genius in American

brewing, dreamed of creating the first national beer, and by the 1870s

the conditions were right to begin making his dream a reality. Backed

by a huge brewery, refrigerated storehouses and rail cars, and a new

process allowing the pasteurization of beer, Busch introduced his new

beer, called Budweiser, in 1876. But the majority of the brewers were

still small operations providing beer for local markets. It would take

industrialization, Prohibition, and post-World War II consolidation to

create the monolithic brewers that dominated the twentieth century.

At the dawn of the twentieth century several factors were

reshaping the American brewing industry. First, large regional brands

grew in size and productive capacity and began to squeeze competi-

tors out of the market. New bottling technologies allowed these

brewers to package and ship beer to ever-larger regions. Such brewers

were aided by new legislation that prohibited the brewing and bottling

of beer on the same premises, thus ending the tradition of the local

brewhouse. ‘‘The shipping of bottled beer,’’ notes Philip Van Munch-

ing in Beer Blast: The Inside Story of the Brewing Industry’s Bizarre

Battles for Your Money, ‘‘created the first real emphasis on brand

identification, since shipping meant labeling, and labeling meant

BEERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

211

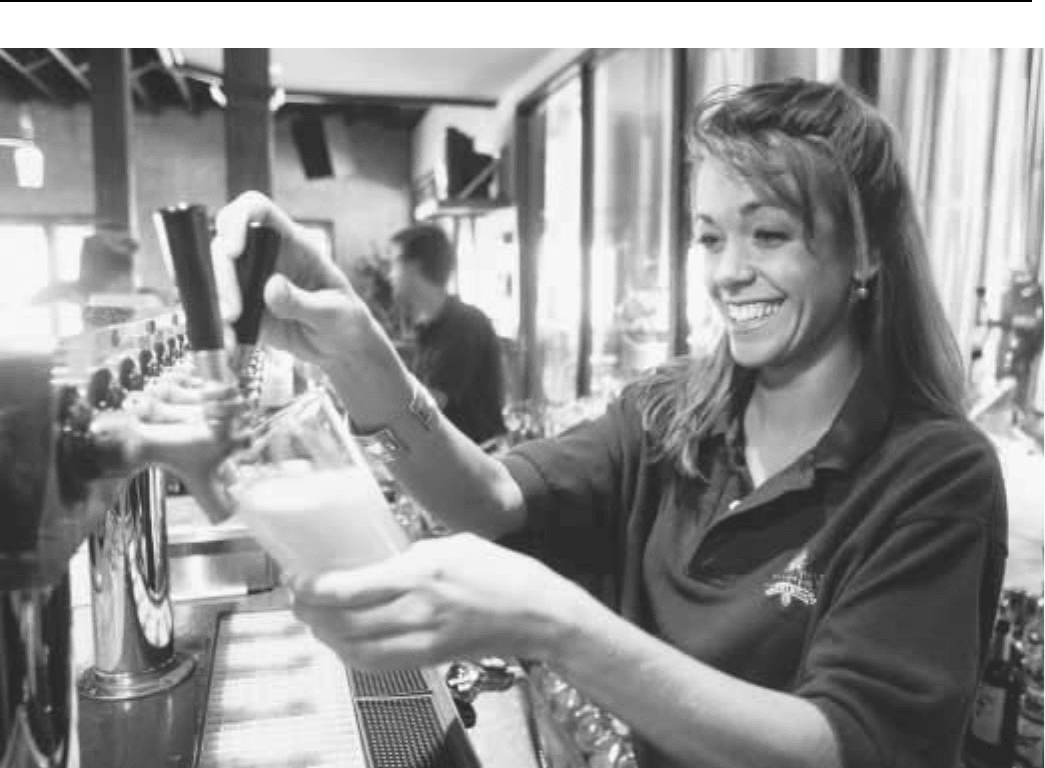

A bartender pours a beer at the Copper Tank Brew Pub in Austin, Texas.

imagery.’’ All these factors helped big brewers get bigger while small

brewers left the industry. By 1910 the number of breweries had

decreased to 1,568, though they produced 53 million barrels of beer a

year. With fewer breweries producing more beer, the stage was set for

the next century of American brewing. There was only one problem:

numbers of Americans supported placing restrictions on alcohol

consumption and they soon found the political clout to get their way.

For a number of years nativist Protestants, alarmed by the social

disorder brought to the United States by the surge of immigrants from

eastern and southern Europe, had been pressing for laws restricting

the sale of alcohol, hoping that such laws would return social order to

their communities. Fueled by anti-German (and thus anti-brewing)

sentiment sparked by Germany’s role in World War I, such groups as

the National Prohibition Party, the Woman’s Christian Temperance

Union, and the Anti-Saloon League succeeded in pressing for legisla-

tion and a Constitutional Amendment banning the ‘‘manufacture,

sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.’’ The Volstead En-

forcement Act, which went into effect on January 18, 1920, made the

brewing of beer punishable under the law. ‘‘What had been a normal

commercial activity one day,’’ writes Penne, ‘‘was a criminal act the

next.’’ Small and medium-sized breweries across the nation closed

their doors, and the big brewers turned their vast productive capacity

to producing near beer (with names like Vivo, Famo, Luxo, Hoppy,

Pablo, and Yip) and other non-alcoholic beverages. As a method of

social control, Prohibition—as the period came to be known—failed

miserably: American drinkers still drank, but now they got their

booze from illicit ‘‘speakeasies’’ and ‘‘bootleggers,’’ which were

overwhelmingly controlled by organized crime interests. Crime in-

creased dramatically during Prohibition (or at least anti-Prohibition

interests made it seem so) and the politicians who were against

Prohibition, energized by the political realignment caused by the start

of the Great Depression and the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt,

repealed Prohibition by December of 1933.

The effects of Prohibition on the brewing industry were dramat-

ic. Only 400 of the country’s 1,568 breweries survived Prohibition,

and half of these failed during the Depression that gripped the country

throughout the 1930s. The big breweries survived, and in the years to

come they would claim an ever-increasing dominance in the Ameri-

can beer market. Big brewers were aided in 1935 by the introduction

of canned beer. Though brewers first put beer in tin or steel cans,

Coors introduced the aluminum can in 1959 and it was quickly

adopted by the entire brewing industry. More and more, beer was a

mass-produced product that could be purchased in any grocery store,

rather than a craft-brewed local product purchased at a local alehouse.

But American brewing did not rebound immediately upon repeal of

Prohibition. The economic troubles of the 1930s put a damper on

BEER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

212

production; in 1940, American brewers produced only 53 million

barrels of beer, ‘‘well below the pre-Prohibition peak of 66 million

barrels,’’ according to Yenne. It would take World War II and the

post-war boom to spark a real resurgence in American brewing.

As World War II drew increasing numbers of American men off

to foreign bases, military leaders wisely decided to permit the sale of

beer on military bases. Brewers obliged by allocating 15 percent of

their production for the troops and, according to Yenne, ‘‘young men

with long-standing loyalties to hometown brews were exposed to

national brands,’’ thus creating loyalty to these brands that they

carried home. Brewers also took advantage of an expanding Ameri-

can economy to increase their output to 80 million barrels annual-

ly by 1945.

The story of post-War American brewing can be summed up in

two words: nationalization and consolidation. Anheuser-Busch, Schlitz,

and Pabst set out to make their beers national brands by building

breweries in every region of the United States. In the years between

1946 and 1951, each of these brewers began to produce beer for the

New York market—once dominated by Ballantine, Rheingold, and

Schaefer—from newly-opened breweries. Soon they built breweries,

giant breweries, on the West Coast and in the South. By 1976

Anheuser-Busch alone had opened 16 new breweries in locations

throughout the United States. The other major brewers followed suit,

but no one could keep up with Anheuser-Busch. By 1957 the

company was selling more beer than any brewer in the United States,

a position it has not relinquished since.

Nationalization was followed by consolidation, as the major

brewers began acquiring smaller brewers at an astonishing pace and

either marketing or burying their brands. According to Van Munch-

ing, ‘‘In the sixties and seventies following the American beer

business was like going to a ball game. To keep track of the players,

you needed a scorecard.’’ G. Heileman of Wisconsin purchased

smaller regional brewers of beers like Old Style, Blatz, Rainier, and

Lone Star; Washington brewer Olympia bought Hamms, but was in

turn bought by Pabst. But the biggest buy came when tobacco giant

Philip Morris purchased the Miller Brewing Company in 1970.

Backed by Philip Morris’s deep pockets, Miller suddenly joined the

ranks of the country’s major brewers. Van Munching claims that the

purchase of Miller ‘‘signaled the end of an era in the brewing

industry: the end of skirmishes fought on a strictly regional scale,

often with different contestants in each of the regions. Now, one

battlefield was brought into sharp focus . . . the whole U.S. of A.’’

From 1970 on, the major national brewers battled fiercely for market

share with a sophisticated arsenal of advertising, promotions, brand

diffusion, and bluster.

In a market in which the major brands had little difference in

taste, the biggest tool the brewers had to increase market share was

advertising. The first brewer to turn its full attention to the promotion

of its product on a national scale was Miller, which in the early 1970s

began an unprecedented push into the sports marketplace. Miller

advertised its brands on every televised sporting event it could get its

hands on, from auto racing to football. While it pitched its flagship

brand, Miller High Life, with the slogans ‘‘If you’ve got the time,

we’ve got the beer’’ and the tag line ‘‘Miller Time,’’ Miller attracted

the most attention with its ads for the relatively new Lite Beer from

Miller that featured drinkers arguing whether the beer ‘‘Tastes

Great’’ or was ‘‘Less Filling.’’ For a time, Miller dominated the

available air time, purchasing nearly 70 percent of network television

sports beer advertising. But Anheuser-Busch wasn’t about to let

Miller outdo them, and they soon joined in the battle with Miller to

dominate the airwaves, first purchasing local television air time and

later outbidding Miller for national programs. With their classy

Budweiser Clydesdales, ‘‘This Bud’s for You,’’ and the ‘‘Bud Man,’’

Budweiser managed to retain their leading market share. Between

them, Anheuser-Busch and Miller owned American television beer

advertising, at least until the others could catch up.

Both Budweiser and Miller devoted significant resources to

sponsoring sporting teams and events in an effort to get their name

before as many beer drinkers as possible. Budweiser sponsored the

Miss Budweiser hydroplane beginning in 1962, and beginning in the

early 1980s regularly fielded racing teams on the NASCAR, NHRA,

and CART racing circuits. Moreover, Budweiser sponsored major

boxing events—including some of the classic championship fights of

the 1980s—and in the late 1990s paired with a number of sportsmen’s

and conservation organizations, including Ducks Unlimited and the

Nature Conservancy. For its part, Miller sponsored awards for

National Football League players of the week and year, funded

CART, NASCAR, and drag racing teams, and in the late 1990s started

construction on a new baseball stadium, called Miller Park, for the

aptly named Milwaukee Brewers. Miller has also put considerable

resources into funding for the arts, both in Milwaukee, where it has

sponsored annual ballet productions, and in other cities throughout

the country. These brewers—and many others—also put their name

on so many t-shirts, hats, banners, and gadgets that beer names

sometimes seemed to be everywhere in American culture.

When American brewers couldn’t expand their market share

through advertising, they tried to do so by introducing new products.

The first such ‘‘new’’ beer was light beer. The Rheingold brewery

introduced the first low-calorie beer, Gablinger’s, in 1967, but the

taste was, according to Van Munching, so ‘‘spectacularly awful’’ that

it never caught on. Miller acquired the rights to a beer called Meister

Brau Lite in 1972 when it purchased the Meister Brau brewery in

Chicago, and they soon renamed the beer and introduced it the same

year as Lite Beer from Miller. Offered to drinkers worried about their

protruding beer bellies, and to women who didn’t want such a heavy

beer, Lite Beer was an immediate success and eventually helped

Miller overtake Schlitz as the number two brewer in the country. Not

surprisingly, it spawned imitators. Anheuser-Busch soon marketed

Natural Light and Bud Light; Coors offered Coors Light; Stroh’s

peddled Old Milwaukee Light. There was even an imported light

beer, Amstel Light.

Light beer was an undoubted success: by 1990, the renamed

Miller Lite led sales in the category with 19.9 million barrels,

followed by Bud Light (11.8 million barrels) and Coors Light (11.6

million barrels). Following the success of light beer, beermakers

looked for other similar line extensions to help boost sales. Anheuser-

Busch introduced LA (which stood for ‘‘low alcohol’’) and others

followed—with Schaefer LA, Blatz LA, Rainier LA, etc; the segment

soon died. In 1985, Miller achieved some success with a cold-filtered,

nonpasteurized beer they called Miller Genuine Draft, or MGD;

Anheuser-Busch followed them into the market with several imita-

tors, the most flagrant being Michelob Golden Draft (also MGD),

with a similar bottle, label, and advertising campaign. Anheuser-

Busch created the dry beer segment when it introduced Michelob Dry,

followed shortly by Bud Dry. Their advertising slogan—‘‘Why ask

why? Try Bud Dry’’—begged a real question: Why drink a dry beer?

Consumers could think of no good reason, and the beers soon

disappeared from the market. Perhaps, thought brewers, an ice beer

would be better. Following Canadian brewer Molson Canada, Miller

BEERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

213

introduced Molson Ice in the United States in 1993; they were, once

again, followed by many imitators and, once again, the category

slowly fizzled after a brief period of popularity.

Though the attempts of American brewers to create new beer

categories appeared to be a comedy of errors, there was reason behind

their madness. Simply put, the market for their beers had grown

stagnant and the same brewers were competing for a market that was

no longer growing substantially. Many brewers sought to expand by

peddling wine coolers or alternative beverages, such as Coors’s Zima

Clearmalt; most hastened their efforts to sell their beer in the

international market. Anheuser-Busch, for example, began to market

its beer in more than 60 countries worldwide. Still, the question was if

American drinkers weren’t drinking the ‘‘new’’ beers produced by

the major brewers, what were they drinking? In the simplest terms,

the answer was that more and more Americans were drinking ‘‘old’’

beers—carefully crafted ales and lagers with far more taste and body

than anything brewed by the ‘‘big boys.’’ Beginning in the late 1970s,

the so-called ‘‘microbrew revolution’’ proved to be the energizing

force in the American beer market.

American capitalism has proved extremely adept at producing

and marketing vast numbers of mass-produced goods, and American

brewers are quintessential capitalists. But with mass production

comes a flattening of distinctions, a tendency to produce, in this case,

beers that all taste the same. Beginning in the late 1970s and

accelerating in the 1980s, American consumers began to express a

real interest in products with distinction—in gourmet coffee (witness

the birth of Starbucks and other gourmet coffee chains), in good cars

(thus rising sales of BMW, Mercedes, and Japanese luxury brands

Lexus and Acura), and in fine clothes (witness the rise of designers

Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein). The changing taste of American

beer drinkers was first expressed as a preference for imported beers,

which surged in sales in the late 1970s. But true beer connoisseurs

soon turned to beer brewed closer to home. In 1977 the New Albion

brewing company in Sonoma, California, offered the first American

‘‘microbrew,’’ the name given to beer brewed in small batches. The

first major microbrewer, the Sierra Nevada Brewing Company of

Chico, California, opened in 1981, and was followed into the market

by a succession of breweries first in the West and then throughout

the country.

One of the first microbrewers to enter the national market was

the contract-brewing Boston Beer Company, producers of the Samuel

Adams Boston Lager and other beers, but for the most part the

microbrew revolution was not about following the path of the big

breweries into national marketing, but rather about producing high

quality ales for the local market. In small- and medium-sized markets

around the country, American beer drinkers were rediscovering the

richness and variety of the brewer’s art. In the microbrewing capital

of the United States, the Pacific Northwest, alehouses can boast of

carrying dozens of beers brewed within a day’s drive. At places like

Fred’s Rivertown Alehouse in Snohomish, Washington, a group

called the Cask Club even joined in the revival of one of the oldest

brewing traditions—cask-conditioned or ‘‘real’’ ales.

Though the microbrew revolution wasn’t big—craft-brewed

beers only accounted for 2.1 percent of the domestic beer market in

1995—it exerted a great influence on the major brewers. Most of the

big brewers responded to the challenge posed by microbrewers by

marketing slightly richer, slightly better beers with ‘‘authentic’’

looking labels. Miller marketed beers under the label Plank Road

Brewery and Michelob promoted its dark and amber beers. Miller

responded most ingeniously by claiming in advertisements that it was

‘‘time for a good old macrobrew,’’ brewed in one of their ‘‘vats the

size of Rhode Island.’’ Meanwhile microbreweries, brewpubs, and

regional specialty brewers kept opening; by 1995 there were 1,034

such breweries in the United States, heralding a return to the abun-

dance of breweries that existed at the turn of the century, and a

dramatic rise from the 60 breweries in existence in 1980.

It comes as no surprise that a drink as popular as beer should play

a role in American entertainment. Beer could have been credited as a

character on the long-running sitcom Cheers (1982-1993), which

featured a group of men who felt most at home sitting in a Boston bar

with a beer in their hands; the biggest beer drinker, Norm, perfected

humorous ways of asking for his beer, and once called out ‘‘Give me a

bucket of beer and a snorkel.’’ Milwaukee’s fictional Schotz Brewery

employed the lead characters in the 1970s sitcom Laverne and Shirley

(1976-1983). When Archie Bunker of All in the Family (1971-1979)

left his union job he opened a bar—Archie’s Place—that served beer

to working class men. The characters on the Drew Carey Show

(1995—) brewed and marketed a concoction they called Buzz Beer,

and signed a professional wrestler to do celebrity endorsements.

Homer Simpson, the father on the animated series The Simpsons

(1989—) swore his allegiance to the locally-brewed Duff Beer. (The

show’s producer, Twentieth Century-Fox, sued the South Australian

Brewing Company when it tried to market a beer under the same

name). Movies have not provided so hospitable a home to beer,

though the 1983 movie Strange Brew followed the exploits of beer

drinking Canadians Bob and Doug McKenzie as they got a job at the

Elsinore Brewery.

In the 1990s, with more beers than ever to choose from,

Americans still turned with amazing frequency to the major brands

Budweiser, Miller, and Coors. Such brands offered not only a

familiar, uniform taste, but were accompanied by a corresponding set

of images and icons produced by sophisticated marketing machines.

Drinkers of the major brands found their beer on billboards, race cars,

television ads, store displays, and t-shirts everywhere they looked; by

drinking a Bud, for example, they joined a community unique to late-

twentieth-century mass culture—a community of consumers. But for

those who wished to tap into the age old tradition of brewing, an

increasing number of brewers offered more authentic fare.

—Tom Pendergast

F

URTHER READING:

Abel, Bob. The Book of Beer. Chicago, Henry Regnery Compa-

ny, 1976.

Grant, Bert, with Robert Spector. The Ale Master. Seattle, Washing-

ton, Sasquatch Books, 1998.

Hernon, Peter, and Terry Ganey. Under the Influence: The Unauthor-

ized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1991.

Jackson, Michael. Michael Jackson’s Beer Companion. Philadelphia,

Running Press, 1993.

Nachel, Marty, with Steve Ettlinger. Beer for Dummies. Foster City,

California, IDG Books Worldwide, 1996.

Plavchan, Ronald Jan. A History of Anheuser-Busch, 1852-1933.

New York, Arno Press, 1976.

Porter, John. All About Beer. Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1975.

BEIDERBECKE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

214

Price, Steven D. All the King’s Horses: The Story of the Budweiser

Clydesdales. New York, Viking Penguin, 1983.

Rhodes, Christine P., editor. The Encyclopedia of Beer. New York,

Henry Holt & Co., 1997.

Van Munching, Philip. Beer Blast: The Inside Story of the Brewing

Industry’s Bizarre Battles for Your Money. New York, Random

House, 1997.

Yenne, Bill. Beers of North America. New York, Gallery Books, 1986.

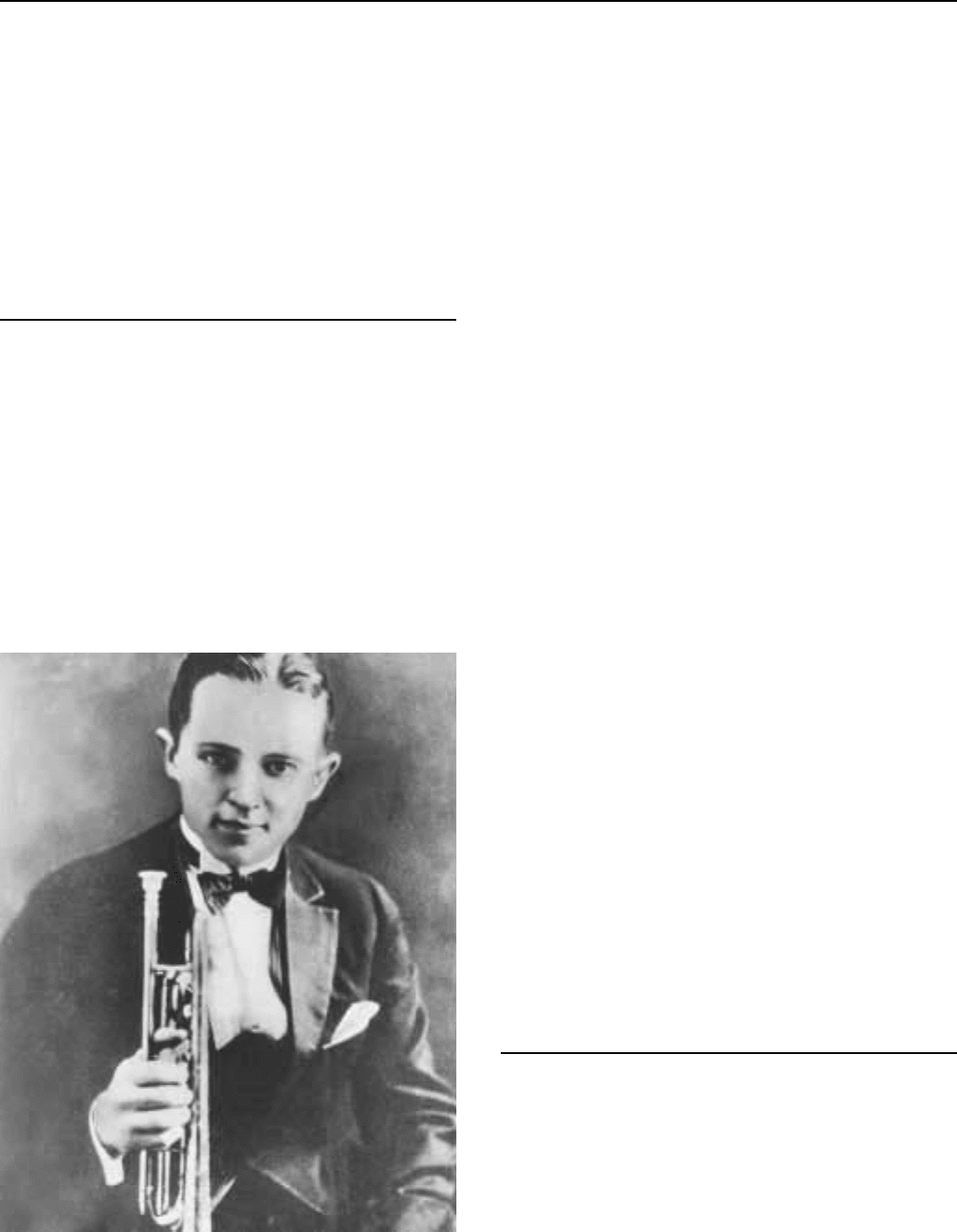

Beiderbecke, Bix (1903-1931)

Leon Bismarck ‘‘Bix’’ Beiderbecke is one of the few white

musicians to have influenced important black musicians. Considered

one of the all-time great jazz artists, he was admired by Louis

Armstrong, who always mentioned Beiderbecke as his favorite trum-

pet player. Beiderbecke actually played cornet, which was also

Armstrong’s first trumpet-like instrument.

Remarkably, Beiderbecke did not hear a jazz record until he was

14. The music of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band became his

inspiration, and he copied the cornet solos verbatim. However, he

resisted any formal musical instruction, and fingered the cornet in an

unorthodox fashion that enabled him to solo with incredible speed. In

common with many jazz musicians of his day, Beiderbicke never

learned to read music very well, either. Rather, he relied upon his

Bix Beiderbecke

great ear for music. Despite his apparent talent, his parents sought to

discourage his musical pursuits. They sent him to Wake Forest

Academy, a military school near Chicago, in the hopes that its strict

discipline would quell his interest in jazz.

Their ploy did not work. Beiderbecke managed to get himself

expelled for cutting classes and soon turned to music full-time,

coming to fame in the 1920s. In 1923, he joined the Wolverines and

recorded with them in 1924. He soon left the Wolverines to join Jean

Goldkette’s Orchestra, but lost the job because of his inability to read

music well. In 1926, he joined Frankie Trambauer’s group and

recorded his piano composition ‘‘In a Mist.’’ In concert with his time,

Beiderbecke lived the life of a ‘‘romantic’’ artist, drinking to excess

and living for his art. Both made him a legend among his contempo-

raries. His tone on the cornet was gorgeous, very different from

Armstrong’s assertive brassy tone. It became a model for a number of

later horn players, including Bunny Berrigan, Harry James, Fats

Navarro, Clifford Brown, and Miles Davis, among others.

Beiderbecke recorded extensively with Eddie Lang, guitar, and

Frankie Trambauer, C-Melody sax. He managed to improve his music

reading enough to work with Jean Goldkette again, and later joined

Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra, the most popular group of his day. In

1929, Beiderbecke returned to Davenport, Iowa, to recuperate from

the ill-effects of his hard drinking. Whiteman treated Beiderbecke

well, paying him his full salary and offering to take him back when he

was well. Beiderbecke never fully recovered. He made a few records

with Hoagy Carmichael before his death in 1931 of lobar pneumonia

and edema of the brain. Beiderbecke’s romantic life and death

inspired Dorothy Baker’s book, Young Man with a Horn, as well as

the movie of the same name. The Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz

Festival continues in Davenport, Iowa. It is billed as Iowa’s Number

One Attraction.

—Frank A. Salamone

F

URTHER READING:

Berton, Ralph. Remembering Bix. New York, Harper & Row, 1974.

Burnett, James. Bix Beiderbecke. London, Cassell & Co., 1959.

Carmichael, Hoagy, and Stephen Longstreet. Sometimes I Wonder.

New York, Hoagy, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1965.

Sudhalter, Richard M., and Philip R. Evans. Bix: Man And Legend.

Arlington House Publishers, 1974.

Belafonte, Harry (1927—)

Singer, actor, and activist Harry Belafonte with his ‘‘Jamaica

Farewell’’ launched the calypso sound in American popular music

and through his performances popularized folk songs of the world to

American audiences. As an actor, Belafonte tore down walls of

discrimination for other minority actors, and as an activist, profound-

ly influenced by the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he fought for the

civil rights of Africans and African Americans for decades. A popular

matinee idol since the 1950s, Belafonte achieved his greatest popu-

larity as a singer. His ‘‘Banana Boat (Day-O)’’ shot to number five on

BELAFONTEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

215

Harry Belafonte

the Billboard pop singles chart in 1957. His Calypso album released

in 1956 was certified gold in 1963 and the 1959 album Belafonte at

Carnegie Hall certified gold in 1961. Belafonte was the first African

American television producer and the first African American to win

an Emmy Award.

Born on March 1, 1927, in New York City, Harold George

Belafonte, Jr. was the son of Caribbean immigrants. His mother,

Melvine Love Belafonte, was from Jamaica and his father, Harold

George Belafonte, Sr., was from Martinique. In 1935, after his father

left the family, Belafonte and his mother moved to her native Jamaica

where Belafonte spent five years attending school and assimilating

the local music. In 1940, he returned to the public schools of New

York but in 1944, at the age of seventeen, dropped out to enter the

U.S. Navy for a two-year stint. In 1948, Belafonte married Julie

Robinson, a dancer.

After seeing a production of the American Negro Theater,

Belafonte knew he wanted to become an actor. He attended the

Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research, studying

under the direction of Erwin Piscator. As a class project, he had to sing

an original composition entitled ‘‘Recognition’’ and after his per-

formance drew the attention of Monte Kay who later became his

agent. Since few acting opportunities opened and Belafonte needed to

support his family, Kay offered him a singing engagement at the

Royal Roost, a jazz night club in New York. After attracting favorable

reviews, Belafonte established himself as a creditable jazz and

popular singer. But by 1950, feeling that he could not continue

singing popular music with a sincere conviction, he abruptly switched

to folk songs and began independently studying, researching, and

adapting folk songs to his repertoire. His folk singing debut in 1951 at

the Village Vanguard in New York’s Greenwich Village was a

smashing success. Belafonte subsequently opened a restaurant cater-

ing to patrons who appreciated folk singing, but it closed in three

years because it was not commercially viable.

Belafonte recorded for Jubilee Records in 1949 and signed with

RCA Victor records in 1956 with his first hit, ‘‘Banana Boat (Day-

O),’’ issued in 1957. He soon launched the calypso craze. While

Belafonte was not a true calypsonian, i.e., one who had grown up

absorbing the tradition, he was instead an innovator and took tradi-

tional calypso and other folk songs, dramatizing, adapting, and

imitating the authentic prototypes, melding them into polished and

consummate musical performances. He was called the ‘‘King of

Calypso,’’ and capitalized on the tastes of the American and Europe-

an markets. His ‘‘Jamaica Farewell,’’ ‘‘Matilda, Matilda,’’ and

‘‘Banana Boat (Day-O)’’ are classics. Guitarist Millard Thomas

became his accompanist. Belafonte also sang Negro spirituals and

work songs, and European folk songs in addition to other folk songs

of the world on recordings and in live concerts. While his hits had

stopped by the 1970s, his attraction as a concert artist continued. He

recorded with such well-known artists as Bob Dylan, Lena Horne,

Miriam Makeba, and Odetta. Belafonte was responsible for bringing

South African trumpeter and bandleader Hugh Masekela and other

South African artists to the United States. In 1988, the acclaimed

album Paradise in Gazankulu was banned in South Africa because of

its depiction of the horrors of apartheid.

Belafonte took singing roles in the theatrical production Alma-

nac in 1953 and opportunities for acting opened up. His first film was

The Bright Road (1953) with Dorothy Dandridge. In 1954, he played

the role of Joe in Carmen Jones, an adaptation of Bizet’s Carmen that

became one of the first all-black movie box-office successes. He

starred in Island in the Sun in 1957 and Odds Against Tomorrow in

1959. In the 1970s, his film credits included Buck and the Preacher

(1972) and Uptown Saturday Night (1974). Belafonte also appeared

in numerous television specials and starred in videos and films

documenting music, including Don’t Stop the Carnival in 1991,

White Man’s Burden in 1995, and Kansas City in 1996.

As a student in Jamaica, Belafonte observed the effects of

colonialism and the political oppression that Jamaicans suffered. He

committed himself to a number of humanitarian causes including

civil rights, world hunger, the arts, and children’s rights. The ideas of

W. E. B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

exerted powerful influences on Belafonte. He participated in marches

with Dr. King and in 1985 helped organize as well as perform on ‘‘We

Are the World,’’ a Grammy Award-winning recording project to raise

money to alleviate hunger in Africa. Due to his civil rights work, he

was selected as a board member of the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference and also served as chair of the memorial fund named after

Dr. King.

Belafonte continues to inspire audiences through his songs and

his passion for racial justice has remained indomitable. He is one of

the leading artists who has broken down barriers for people of color,

made enormous contributions to black music as a singer and produc-

er, and succeeded in achieving rights for oppressed people. His music,

after more than forty years, still sounds fresh and engaging. Belafonte’s

genius lies in his ability to sway an audience to his point of view. His

BELL TELEPHONE HOUR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

216

charisma, voice, and acting abilities enable him to make any song his

own while at the same time keeping his audience spellbound. Selected

songs from his repertoire will remain classics for generations to come.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Fogelson, Genia. Harry Belafonte: Singer and Actor. Los Angeles,

Melrose Square Publishing Company, 1980.

Shaw, Arnold. Harry Belafonte: An Unauthorized Biography. Phila-

delphia, Chilton Company, 1960.

The Bell Telephone Hour

Every Monday night for 18 years, from April 29, 1940, America

was treated to The Bell Telephone Hour, a musical feast broadcast by

NBC Radio. Featuring the 57-piece Bell Telephone Orchestra, direct-

ed by Donald Voorhees, who composed their theme, ‘‘The Bell

Waltz,’’ the program brought the best in musical entertainment across

a broad spectrum, in a format that made for easy and popular listening.

Vocalists James Melton and Francia White performed with the

orchestra until April 27, 1942, when the program initiated its ‘‘Great

Soloists’’ tradition, showcasing individual artists of distinction. Among

the many ‘‘greats’’ were opera stars Helen Traubel, Marion Ander-

son, and Ezio Pinza, concert pianists Jose Iturbi and Robert Casadesus,

leading artists in jazz such as Benny Goodman, top Broadway stars

such as Mary Martin, and popular crooners, including Bing Crosby.

NBC took The Bell Telephone Hour off the air in 1958, but

revived it for television from October 9, 1959, with Donald Voorhees

and the Orchestra still in place. Always stylish and elegant in

presentation, the small-screen version ran for 10 years, offering the

same eclectic mix as the radio original for eight of them. The visual

medium allowed the inclusion of dance, and viewers were treated to

appearances by ballet idol Rudolf Nureyev and veteran tap-dancer

Ray Bolger, among others. On April 29, 1960, the program memora-

bly brought Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta, The Mikado, to television

with a cast led by soprano Helen Traubel as Katisha and comedian

Groucho Marx as the Lord High Executioner.

In 1966, however, the show abandoned its established format in

favor of documentary films. Subjects included such established

performers as pianist Van Cliburn, conductor Zubin Mehta, and jazz

man Duke Ellington, but the program lasted only two more years,

ending a chapter in broadcasting history on April 26, 1968.

—James R. Belpedio

F

URTHER READING:

Buxton, Frank, and Bill Owen. The Big Broadcast. New York, Viking

Press, 1972.

Dunning, John. Tune In Yesterday: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Old

Time Radio. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1976.

Hickerson, Jay. The New, Revised Ultimate History of Network Radio

Programming and Guide to All Circulating Shows. Hamden,

Connecticut, Jay Hickerson, 1996.

Museum of Broadcasting. The Telephone Hour: A Retrospective.

New York, Museum of Broadcasting, 1990.

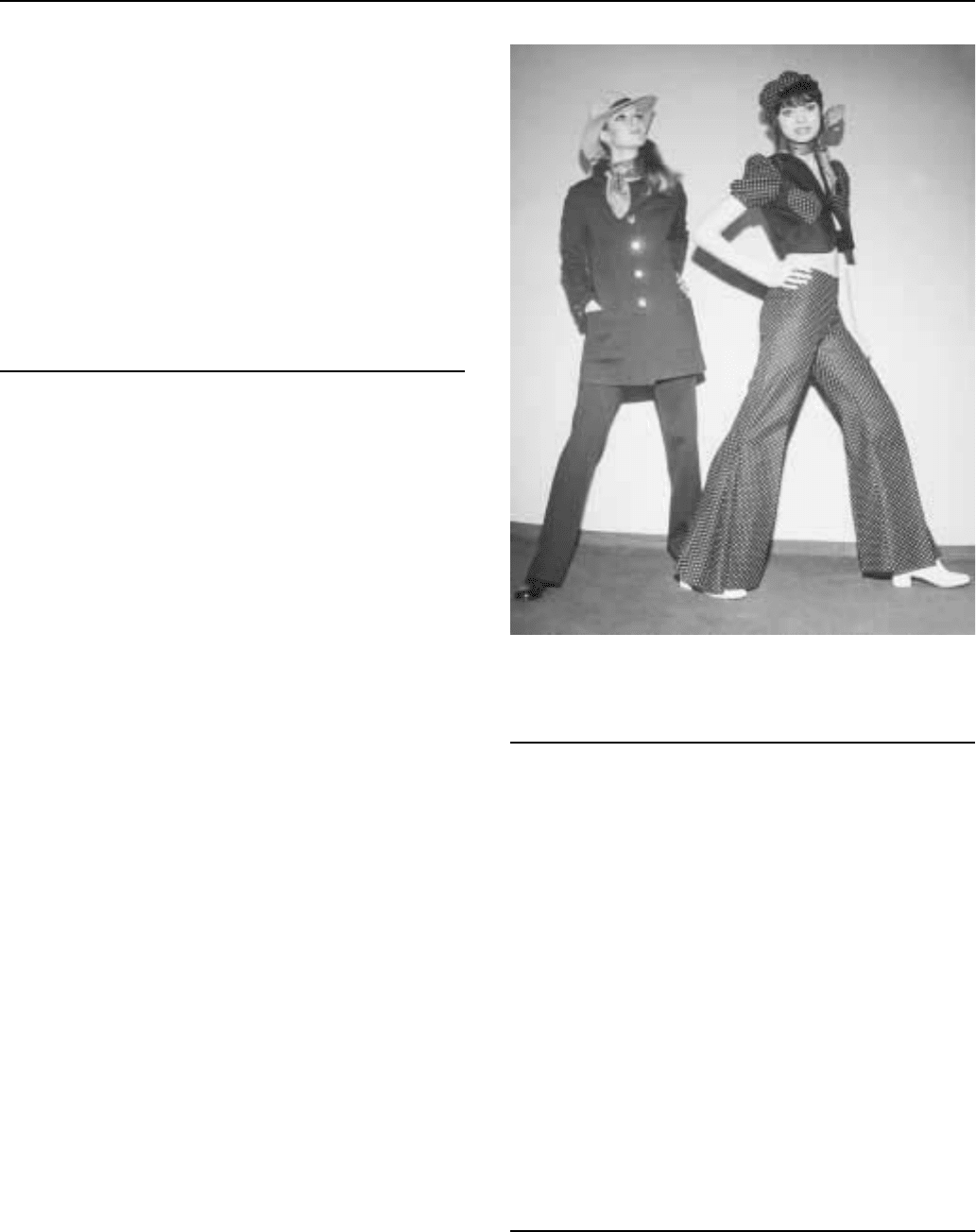

Two women modeling bellbottoms.

Bellbottoms

Bellbottomed trousers, named for the bell-shaped cut of the

cuffs, have been worn by sea-farers since the 17th century. While

sailors prefer the cut because the wide bottoms of the trousers make

them easy to roll up for deck-swabbing duty, young people bought the

trousers from navy surplus stores in the 1960s because the fabric was

cheap and durable. Bellbottoms flattered the slim, unisex figure in

vogue during the late 1960s and 1970s, and soon designers were

turning out high-price versions of the navy classic. In the 1990s, the

revival of 1970s fashion has seen the return of bellbottoms, especially

as jeans.

—Deborah Broderson

F

URTHER READING:

Blue Jeans. London, Hamlyn, 1997.

Dustan, Keith. Just Jeans: The Story 1970-1995. Kew, Victoria,

Australian Scholarly Press, 1995.

Belushi, John (1949-1982)

The name John Belushi conjures images of sword-wielding

Samurai, cheeseburger-cooking Greek chefs, mashed-potato spewing

BELUSHIENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

217

human zits, and Ray Ban wearing ex-cons on a ‘‘mission from God.’’

But his short life is also a popular metaphor for drug abuse and wild

excess. His acting and comedy, undeniably energetic and highly

creative, are overshadowed by his death, a tabloid cliché revisited

every time another Hollywood star overdoses on drugs or alcohol.

In part, this sad legacy is influenced by Bob Woodward’s

clinical and unflattering biography, Wired (1984), in which Belushi is

described as an insecure man who turns to cocaine and heroin to

bolster his self-esteem. Woodward concluded that Belushi’s extremes

in personality were a representation of the 1970s and the drug-

obsessed entertainment industry of the time. Yet this legacy is also

inspired in part by Belushi’s own stage, television, and movie

personae, best exemplified in popular myth by his portrayal of the

anti-establishment, hedonistic fraternity bum Bluto Blutarsky of

National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978). The dean’s admonition

that ‘‘fat, drunk, and stupid is no way to go through life’’ can be seen

as an unbidden warning to Belushi.

Belushi first came to public notice as a member of Chicago’s

Second City comedy troupe. Led by Del Close, Second City used

improvisational skits to entertain the audiences. While he later

credited Close for teaching him how to be a part of an ensemble,

Belushi’s intense energy and raucous attitude soon began pushing the

bounds of the troupe’s comedy. In spite of Close’s insistence that they

were all a team, local reviews soon made it clear that Belushi was the

‘‘star’’ of the show. This soon earned him the notice of Tony Hendra,

producer-director of the forthcoming National Lampoon Magazine’s

musical satire Lemmings. Belushi fascinated Hendra, and he offered

him the role of the manic emcee that instigates the mass suicide of the

audience in Lemmings.

At that time, National Lampoon Magazine was at the forefront of

alternative comedy, the borderline humor that mocked religion, sex,

illness, and even death. Lemmings was envisioned as an off-Broad-

way send-up of the Woodstock concert that would showcase the

magazine’s brand of humor. For Belushi, it was a marriage made in

heaven. The show got rave reviews, its original six-week run being

extended for ten months. In reviews, Belushi was singled out for

particular praise, his performance outshining the rest of the cast,

including newcomer Chevy Chase. He tied himself more closely with

National Lampoon by working as a writer, director, and actor of the

National Lampoon Radio Hour.

In the spring of 1975 Lorne Michaels asked Belushi to join the

regular cast of a new show he was preparing for NBC television.

Envisioned as a show to appeal to the 18-to-34 audience, Saturday

Night Live (SNL) was broadcast live from the NBC studios in New

York. The live aspect gave these younger audiences a sense of

adventure, of never knowing what was going to happen next. The

cast, which also included Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd, and others,

billed themselves as the ‘‘Not Ready for Prime Time Players,’’ and

set about redefining American television comedy in the irreverent

image of Britain’s Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Belushi was at first overshadowed by Chase, whose suave

sophistication appealed to the viewers. He initially came to the

audience’s attention as a manic weatherman sitting next to Chase’s

deadpan ‘‘Weekly Update’’ anchorman, ending with his catchphrase

‘‘But nooooooooooooo!’’ When Chase departed for Hollywood at the

end of the first season, Belushi became the viewers’ new favorite. His

most memorable SNL performances included the lunatic weather-

man, a Samurai warrior with a short fuse and a long sword, the

resentful leader of a band of killer bees, Joe Crocker, and a Greek chef

that would cook only cheeseburgers. He cultivated the image of ‘‘bad

boy’’ both on and off screen: a picture of the third season SNL cast has

a grim looking Belushi standing to one side, eyes covered with sun

glasses, cigarette in hand, with Gilda Radner’s arm draped over his

shoulder. While some of the others tried to affect a similar look

(especially Aykroyd), only Belushi seemed to truly exude attitude.

Like Chase, Belushi was also looking to advance his career in

Hollywood. He began his movie career with a bit part in Jack

Nicholson’s poorly received comedy-western Goin’ South (1978).

Months before it was released, however, his second movie project

was in the theaters and thrilling audiences. Returning to National

Lampoon, he was cast as the gross undergraduate Bluto Blutarsky in

John Landis’ National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978).

Based in part on co-writer Chris Miller’s college experiences in

the 1960s, Animal House begins innocently enough with two fresh-

men seeking to pledge to the Delta House fraternity, a collection of

politically incorrect and incorrigible students whose most intelligent

member is averaging less than a 2.0 grade point average. The strait-

laced dean of the school is determined to see Delta evicted from

campus and its members expelled. The remainder of the movie is a

series of skits about the run-ins between the dean and Delta House.

Among these skits is Belushi’s potato-spewing imitation of a zit.

Bluto drank excessively, lived only to party, disrupted the

campus, and urinated on the shoes of unsuspecting freshmen. It is

Belushi’s portrayal of Bluto that is one of the movie’s most enduring

images, virtually typecasting him as a gross, excessive, drinking party

animal. For most of the movie his character speaks in grunts, his big

monologue coming near the end when he encourages a demoralized

Delta House to take its revenge on the dean: ‘‘What? Over? Did you

say ‘over’? Nothing is over until we decide it is! Was it over when the

Germans [sic] bombed Pearl Harbor? Hell no!’’ The movie ends with

a Delta-inspired riot at the college’s Homecoming Parade. The

characters then all head off into the sunset, with captions revealing

their eventual fates (Bluto’s was to become a senator).

John Belushi as the Samurai Warrior dry cleaner on Saturday Night Live.

BEN CASEY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

218

The movie was vintage National Lampoon, and moviegoers

loved it. It became the biggest earner of the year, critics attributing

much of its success to Belushi. He wasn’t so fortunate with his next

movie, the romantic comedy Old Boyfriends (1979). To the public,

Belushi was Bluto and the Samurai, and they had difficulty relating to

him in a romantic role. As Wild Bill Kelso, in Steven Speilberg’s flop

1941 (1979), Belushi played another character much like Bluto, this

time in goggles and chewing on a stubby cigar.

During this time, Aykroyd and Belushi were cooperating on

writing sketches for SNL, their partnership based on friendship and

common interests. During a road trip they discovered a common love

of blues music, and they returned to New York with an idea to develop

a warm-up act for SNL, the Blues Brothers. Studio audiences were

enthusiastic, and the actors convinced the producers to put the Blues

Brothers on the telecast. The reaction was phenomenal. The Blues

Brothers soon followed up their television success with a best-selling

album (Briefcase Full of Blues), a hit single (‘‘Soul Man’’) and a

promotional tour. To Belushi, this was a dream come true: a rock band

on tour with a best-selling record. The two stars decided it was time to

quit television and concentrate on their movie and music careers.

Aykroyd, meanwhile, had teamed up with John Landis to bring

the band to the big screen. The script they came up with began with

Jake Blues (Belushi) being released from Joliet State Penitentiary and

returning with his brother Elwood (Aykroyd) to the orphanage where

they were raised. Learning it is to close unless they can get $5,000, the

brothers decide to put their band back together. The first part of the

movie concerns their attempts to find the rest of the band, while the

second half involves the band’s efforts to raise the money. Through-

out, however, the brothers get involved in many car chases, destroy-

ing a mall in one scene and many of the Chicago Police Department’s

cars in another.

The Blues Brothers opened in 1980 to a mixed reception. The

film was mainly criticized for the excess of car chases, but this is a

part of the cult status The Blues Brothers achieved. The Animal House

audience loved it, seeing the return of the Belushi they had missed in

his other movies. While his character was not Bluto, it was the

familiar back-flipping, blues-howling Joliet Jake from SNL. The

opening scenes of the film further reinforced Belushi’s bad-boy

image, as his character is released from jail, promptly to go on the run

from the police. Most critics, however, thought it was terrible, and one

went so far as to criticize Landis for keeping Belushi’s eyes covered

for most of the movie with Jake’s trademark Ray Bans.

Belushi had already moved on to his first dramatic role as

reporter Ernie Souchak in Continental Divide (1981). He received

good reviews, most of them expressing some surprise that he could do

a dramatic role. The public, however, wanted still more of Bluto and

Joliet Jake. Continental Divide barely broke even. He then returned to

comedy, working on Neighbors (1981) with Aykroyd. The movie was

a critical and box office disaster, in no small part due to the director’s

idea of having the partners switch roles, with Belushi playing the

straight man to Aykroyd’s quirky neighbor. The experience con-

vinced Belushi that he needed more control of his movie projects, so

he began working on a revision of the script for his next role in a

movie called Noble Rot. He envisioned the role as a return to the Bluto

character that his audience was demanding. However, by this time he

was taking heroin. He died of a drug overdose before completing

Noble Rot.

Sixteen years after his death (almost to the day) National

Enquirer gave him the centerpiece of its story on unsolved Holly-

wood mysteries (March 3, 1998), rehashing conspiracy theories

surrounding his death. His death had raised some questions, leading

his widow, writer Judy Jacklin Belushi, to approach Woodward to

investigate it. The result was Wired, more of an examination of

Belushi’s descent into drugs than a balanced portrait of the actor’s

life. Later, Belushi’s family and friends were incensed when the book

was made into a movie, which Rolling Stone called a ‘‘pathetic

travesty’’ and an ‘‘insult’’ to his memory. In response to the book and

the movie Jacklin published her own autobiography, Samurai Widow

(1990), which Harold Ramis described as the perfect antidote to

Wired. During the 1990s, a new generation discovered the actor and

comedian that was John Belushi, while leaving his older fans wonder-

ing about what could have been. As one biography noted, Belushi

helped to develop and make popular an energetic, creative form of

improvisational comedy that continued to entertain audiences.

—John J. Doherty

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Belushi, John.’’ Current Biography Yearbook. 1980.

Jacklin Belushi, Judy. Samurai Widow. New York, Carroll and

Graf, 1990.

John Belushi: Funny You Should Ask. Videocassette produced by Sue

Nadell-Bailey. Weller/Grossman Productions, 1994.

Vickery-Bareford, Melissa. ‘‘Belushi, John.’’ American National

Biography. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Woodward, Bob. Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John

Belushi. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Ben Casey

The medical drama Ben Casey premiered in October 1961 and

soon became the most popular program on ABC. It featured Vince

Edwards as the intensely handsome young neurosurgeon at a large

metropolitan hospital. The wise Dr. Zorba, who was played by

veteran actor Sam Jaffe, mentored him in his efforts to combat disease

and the medical establishment. The younger physician’s brooding,

almost grim, manner echoed the show’s tensely realistic tone. The

series often confronted controversial subjects and was praised for

accurately presenting medical ethics and dilemmas. Each episode

began with a voice intoning the words ‘‘Man. Woman. Birth. Death.

Infinity’’ as the camera focused on a hand writing the symbols for the

words, thus dramatically announcing the somber subject matter of the

show. The series ended in 1966. Contemporary viewers have come to

associate Ben Casey with other medical programs like Dr. Kildare

and Marcus Welby, M.D. in that they all tended to project the image of

the ‘‘perfect doctor.’’

—Charles Coletta

FURTHER READING:

Castleman, Harry, and Walter Podrazik. Harry and Wally’s Favorite

TV Shows. New York, Prentice Hall Press, 1989.

Harris, Jay. TV Guide: The First 25 Years. New York, New American

Library, 1980.