Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BATMANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

189

The AIDS epidemic, which claimed gay men as some of its

earliest victims, caused many public health officials and frightened

patrons to recommend the bathhouses be closed, though others feared

that such a move would only force sexual activity underground,

beyond the reach of counseling, besides erasing the gains of gay

liberation and leading to the repressive eradication of gay culture. The

owners of the baths fought the closures, but most of them were

shuttered by 1985. By the 1990s, gay baths had re-emerged in many

large cities. Some have returned in the guise of the shadowy venues of

pre-liberation days; others have re-opened as private sex clubs, taking

great precautions to educate customers and enforce rules of safe sex

by such means as installing video surveillance cameras and hiring

‘‘lifeguards’’ to monitor sexual activity.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Bayer, Ronald. ‘‘AIDS and the Gay Community: Between the

Specter and the Promise of Medicine.’’ Social Research. Decem-

ber 1985.

Bolton, Ralph, John Zincke, and Rudolf Mak. ‘‘Gay Baths Revisited:

An Empirical Analysis.’’ GLQ. Vol. 1, 1994.

Holleran, Andrew. ‘‘Steam, Soap, and Sex.’’ The Advocate. Octo-

ber 6, 1992.

Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On. New York, Penguin, 1988.

Batman

Batman is one of the most popular and important characters

created for comic books. In the entire pantheon of comic-book

superheroes, only Superman and Spider-Man rival him in signifi-

cance. Among the handful of comic-book characters who have

transcended the market limitations of the comic-book medium, Batman

has truly become an American cultural icon and an international

marketing industry in and of himself.

Batman was born out of DC editor Vincent Sullivan’s desire to

create a costumed character to exploit the recent success of DC’s first

superhero, Superman. Taking inspiration from various Hollywood

adventure, horror, and gangster movies, cartoonist Bob Kane pre-

pared a design for a masked crime-fighter in the costume of a bat in

1939. He then consulted with writer Bill Finger, who contributed to

the vigilante concept ideas derived from pulp magazines. The result-

ing character was thus visually and thematically a synthesis of the

most lurid and bizarre representations of popular culture available to a

1930s mass audience. It was a concept seemingly destined for either

the trashcan or comic-book immortality.

Like Superman, Batman wore a costume, maintained a secret

identity, and battled the scourge of crime and injustice. But to anyone

who read the comic books, the differences between the two leading

superheroes were more striking than the similarities. Unlike Super-

man, Batman possessed no superhuman powers, relying instead upon

his own wits, technical skills, and fighting prowess. Batman’s mo-

tives were initially obscure, but after a half-dozen issues readers

learned the disturbing origins of his crime-fighting crusade. As a

child, Bruce Wayne had witnessed the brutal murder of his mother

Adam West as Batman.

and father. Traumatized but determined to avenge his parents’ death,

Wayne used the fortune inherited from his father to assemble an

arsenal of crime-fighting gadgets while training his body and mind to

the pinnacle of human perfection. One night when Wayne sits

contemplating an appropriate persona that will strike fear into the

heats of criminals, a bat flies through the window. He takes it as an

omen and declares, ‘‘I shall become a bat!’’

Kane and Finger originally cast Batman as a vigilante pursued by

the police even as he preyed upon criminals. Prowling the night,

lurking in the shadows, and wearing a frightening costume with a

hooded cowl and a flowing Dracula-like cape, Batman often looked

more like a villain than a hero. In his earliest episodes, he even carried

a gun and sometimes killed his opponents. The immediate popularity

of his comic books testified to the recurring appeal of a crime-fighter

who appropriates the tactics of criminals and operates free of legal

constraints. As Batman himself once put it, ‘‘If you can’t beat

[criminals] ‘inside’ the law, you must beat them ‘outside’ it—and

that’s where I come in!’’

Batman’s early adventures were among the most genuinely

atmospheric in comic-book history. He waged a grim war against

crime in a netherworld of gloomy castles, fog-bound wharves, and the

dimly lit alleys of Gotham City—an urban landscape that seemed

perpetually enshrouded in night. Bob Kane was one of the first comic-

book artists to experiment—however crudely—with unusual angle

shots, distorted perspectives, and heavy shadows to create a disturb-

ing mood of claustrophobia and madness. These early classic issues

also rank among the most graphically violent of their time. Murder,

brutality, and bloodshed were commonplace therein until 1941, when

BATMAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

190

DC responded to public criticism by instituting a new code of

standards to ‘‘clean up’’ its comic books. As a result Batman’s

adventures gradually moved out of the shadows and became more

conventional superhero adventure stories.

The addition of Batman’s teenage sidekick Robin also served to

lighten the mood of the series. Kane and Finger introduced Robin,

who, according to Kane, was named after Robin Hood, in the April

1940 issue of Detective Comic. They hoped that the character would

open up more creative possibilities (by giving Batman someone to

talk to) and provide a point of identification for young readers. Like

Bruce Wayne, who adopts the orphaned youth and trains him in the

ways of crime fighting, young Dick Grayson witnessed the murder of

his parents.

Robin has been a figure of some controversy. Many believed that

the brightly-colored costumed teenager was obnoxious and detracted

too much from the premise of Batman as an obsessed and solitary

avenger. Oftentimes it seemed that Robin’s principle role was to be

captured and await rescue by Batman. In his influential 1954 polemic

against comic books, Seduction of the Innocent, Dr. Frederick Wertham

even charged that the strange relationship between Batman and Robin

was rife with homosexual implications. Nevertheless, the longevity

and consistent commercial success of the Batman and Robin team

from the 1940s to the 1960s suggested that the concept of the

‘‘Dynamic Duo’’ was popular with most readers.

Much of Batman’s popularity over the decades must be attribut-

ed to his supporting cast of villains—arguably the cleverest and most

memorable rogues gallery in comic books. Ludicrous caricatures

based upon single motifs, villains like Cat Woman, Two-Face, the

Penguin, and the Riddler were perfect adversaries for the equally

ludicrous Batman. Without question, however, the most inspired and

most popular of Batman’s villains has always been the Joker. With his

white face, green hair, purple suit, and perpetual leering grin, the

homicidal Joker is the personification of sheer lunacy, at once

delightful and horrifying. The laughing Joker was also the ideal

archenemy for the stoic and rather humorless Batman, often upstag-

ing the hero in his own comic book.

After years of strong sales, Batman’s share of the comic-book

market began to decline in the early 1960s. Facing stiff competition

from the hip new antihero superheroes of Marvel Comics (Spider-

Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four), Batman and his peers at DC

epitomized the comic-book ‘‘Establishment’’ at a time when anti-

establishment trends were predominating throughout youth culture.

In 1966, however, Batman’s sales received a strong boost from a

new source—television. That year the ABC television network launched

the prime-time live-action series Batman. The campy program was

part of a widespread trend whereby American popular culture made

fun of itself. The Batman show ridiculed every aspect of the comic-

book series from the impossible nobility of Batman and Robin

(portrayed respectively by actors Adam West and Burt Ward, who

both overacted—one would hope—deliberately) to the bewildering

array of improbable gadgets (bat-shark repellent), to comic-book

sound effects (Pow! Bam! Zowie!?). For a couple of years the show

was a phenomenal hit. Film and television celebrities like César

Romero (the Joker), Burgess Meredith (the Penguin), and Julie

Newmar (Cat Woman) clamored to appear on the show, which

sparked a boom in sales of toys, t-shirts, and other licensed bat-

merchandise. Sales of Batman’s comic book also increased dramati-

cally for several years. But the show’s lasting impact on the comic

book was arguably a harmful one. For by making the entire Batman

concept out to be a big joke, the show’s producers seemed to be

making fun of the hero’s many fans who took his adventures

seriously. At a time when ambitious young comic-book creators were

trying to tap into an older audience, the Batman show firmly rein-

forced the popular perception that comic books were strictly for

children and morons.

New generations of writers and artists understood this dilemma

and worked to rescue Batman from the perils of his own multi-media

success. Writer Dennis O’Neil and artist Neal Adams produced a

series of stylish and very serious stories that did much to restore

Batman to his original conception as a nocturnal avenger. These

efforts did not reverse Batman’s declining sales throughout the

1970s—a bad time for comic-book sales generally—but they gave the

comic book a grittier and more mature tone that subsequent creators

would expand upon.

In the 1980s and 1990s writers have explored the darker implica-

tions of Batman as a vigilante seemingly on the brink of insanity. In a

1986 ‘‘graphic novel’’ (the trendy term given to ‘‘serious’’ comic

books—with serious prices) titled Bat Man: The Dark Knight Re-

turns, writer Frank Miller cast the hero as a slightly mad middle-aged

fascist out to violently purge a dystopian future Gotham City gutted

by moral decay. The success of The Dark Knight Returns sparked a

major revival in the character’s popularity. A series of graphic novels

and comic-book limited-series, including Batman: Year One (1987),

Batman: the Killing Joke (1988), and Batman: Arkham Asylum

(1989), delved into the most gothic, violent, and disturbing qualities

of the Batman mythos and proved especially popular with contempo-

rary comic-book fans.

More importantly in terms of public exposure and profits were

the much-hyped series of major motion picture releases produced by

DC Comics’ parent company Warner Brothers featuring characters

from the Batman comic book. Director Tim Burton’s Batman with

Michael Keaton in the title role and Jack Nicholson as the Joker was

the most successful both commercially and critically. But three

sequels to date have all generated impressive box office receipts,

video sales, and licensing revenue while introducing DC’s superhero

to new generations of comic-book readers. Also in the 1990s, a

syndicated Batman animated series produced by the Fox network has

managed the delicate task—never really achieved by the live-action

films—of broadening the character’s media exposure while remain-

ing true to the qualities of the Batman comic books.

Batman is one of the few original comic-book characters to have

generated more popular interest and revenue from exposure in media

other than comic books. But Batman is first and foremost a product of

comic books, and it is in this medium where he has been most

influential. The whole multitude of costumed avengers driven to

strike fear into the hearts of evil-doers owe much to Bob Kane and Bill

Finger’s Batman—the original comic-book caped crusader.

—Bradford Wright

F

URTHER READING:

Daniels, Les. DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic

Book Heroes. Boston, Little Brown, 1995.

The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told. New York, Warner

Books, 1988.

Kane, Bob, with Tom Andrae. Batman and Me: An Autobiography of

Bob Kane. Forestville, California, Eclipse Books, 1989.

BAYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

191

Pearson, Robert E., and William Uricchio, ed. The Many Lives of the

Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. New

York, Routledge, 1991.

Vaz, Mark Cotta. Tales of the Dark Knight: Batman’s First Fifty

Years, 1939-1989. New York, Ballantine, 1989.

Baum, L. Frank (1856-1919)

With The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), L. Frank Baum

created a new kind of plain-language fairy tale, purely American,

modern, industrial, and for the most part non-violent. He said in his

introduction that the book ‘‘was written solely to please children of

today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the

wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares

are left out.’’ The Wizard of Oz—‘‘Wonderful’’ was dropped in later

printings—became an institution for generations of children. Rein-

forced by the 1939 MGM film, the story and its messages quickly

became a part of American culture. The belief that the power to fulfill

your deepest desires lie within yourself, that good friends can help

you get where you are going, and that not all Wizards are for real has

offered many comfort through turbulent times.

The hero of the story—young Dorothy of Kansas, an orphan who

lives with her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry—is a plucky and resourceful

American girl. Yanked by a cyclone into Oz, she accidentally kills the

Wicked Witch of the East and is given the witch’s silver (changed to

ruby in the 1939 movie) shoes. In hope of getting home again,

Dorothy, with her little dog Toto, sets off down the Yellow Brick

Road—to the Emerald City, of course—to ask the Wizard for help.

Along the way, she meets the Scarecrow in search of a brain, the Tin

Woodman who desires a heart, and the Cowardly Lion who is after

courage. Following the storyline of most mythical quests, the friends

encounter numerous adventures and must overcome great obstacles

before realizing their destiny. The Wizard turns out to be a humbug,

but after Dorothy destroys the Wicked Witch of the West by melting

her with a bucket of water, he provides her friends with symbols of

what they already have proven they possess. The book ends with

Dorothy clicking her silver shoes together and being magically

transported home, where her aunt and uncle have been awaiting

her return.

In the Wizard of Oz series, Baum left out the dark, scary

underbelly of the original Grimm fairy tales and created a world

where people do not die and everyone is happy. He also incorporated

twentieth-century technology into the books, and used recognizable

characters and objects from American life such as axle grease,

chinaware, scarecrows, and patchwork quilts. Although Baum poked

gentle fun at some aspects of American life—such as the ‘‘humbug’’

nature of government—The Wizard of Oz goes directly to biting

satire. Dorothy is a girl from the midwest (typical American) who

meets up with a brainless scarecrow (farmers), a tin man with no heart

(industry), a cowardly lion (politicians), and a flashy but ultimately

powerless wizard (technology). It presents an American Utopia

where no one dies, people work half the day and play half the day, and

is a place where everyone is kind to one another. Ray Bradbury

referred to the story as ‘‘what we hope to be.’’

Lyman Frank Baum was born on May 15, 1856 in Chittenango,

New York. His childhood, by all accounts, was happy, marred only by

a minor heart condition. For his fourteenth birthday, his father gave

him a printing press, with which young Frank published a neighbor-

hood newspaper. His 1882 marriage to Maud Gage, daughter of

women’s rights leader Matilda Joslyn Gage, was also a happy one;

Frank played the role of jovial optimist, and Maud was the discipli-

narian of their four sons.

Baum worked as an actor, store owner, newspaper editor,

reporter, and traveling salesman. In 1897, he found a publisher for his

children’s book Mother Goose in Prose, and from then on was a full-

time writer. Baum teamed up with illustrator W. W. Denslow to

produce Father Goose, His Book in 1899 and then The Wonderful

Wizard of Oz in 1900. The book, splashed with color on almost every

page, sold out its first edition of 10,000 copies in two weeks. Over

four million copies were sold before 1956, when the copyright

expired. Since then, millions more copies have been sold in regular,

abridged, Golden, pop-up, and supermarket versions.

In 1902, Baum helped produce a hit musical version of his book,

which ran until 1911, at which point the Baums moved to a new

Hollywood home, ‘‘Ozcot.’’ In spite of failing health, he continued to

write children’s books, producing nearly 70 titles under his own name

and seven pseudonyms including, as Edith Van Dyne, the popular

Aunt Jane’s Nieces series. Inundated with letters from children asking

for more about Dorothy and Oz, Baum authored 14 Oz books

altogether, each appearing annually in December. After Baum’s

death, the series was taken over by Ruth Plumly Thompson; others

have since continued the series.

The books spawned a one-reel film version in 1910, a feature-

length black and white film in 1925, a radio show in the 1930s

sponsored by Jell-O, and, in 1939, the classic MGM movie starring

Judy Garland, which guaranteed The Wizard of Oz’s immortality.

Beginning in 1956, the film was shown on television each year,

bringing the story to generations of children and permanently ingraining

it into American culture.

—Jessy Randall

F

URTHER READING:

Baum, Frank Joslyn, and Russell P. Macfall. To Please A Child: A

Biography of L. Frank Baum, Royal Historian of Oz. Chicago,

Reilly & Lee, 1961.

Gardner, Martin, and Russel B. Nye. The Wizard of Oz & Who He

Was. East Lansing, Michigan State University Press, 1957.

Hearn, Michael Patrick. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. New York,

Clarkson Potter, 1973.

Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a

New American Culture. New York, Pantheon Books, 1993.

Riley, Michael O. Oz and Beyond: The Fantasy World of L. Frank

Baum. Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 1997.

Bay, Mel (1913-1997)

Founder of Mel Bay Publications, Melbourne E. Bay was the

most successful author and publisher of guitar method books in the

late twentieth century. Born in Missouri, Bay became a popular self-

taught guitarist and banjo player in the region. He established himself

BAY OF PIGS INVASION ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

192

as a music teacher in St. Louis, and in 1947 began to write and publish

guitar method materials; eventually he added instructions for playing

other instruments, and by the 1990s his corporation also produced

instructional videos.

Bay’s books sold by the millions, and their quality earned Bay

many awards and honors. Among others, Bay received the Lifetime

Achievement Awards from the American Federation of Musicians

and the Guitar Foundation of America, as well as a Certificate of

Merit from the St. Louis Music Educators Association. St. Louis also

celebrated Mel Bay Day on October 25, 1996. He died on May 14,

1997, at the age of 84.

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Melbourne Bay.’’ American Music Teacher. Vol. 47, No. 1, Au-

gust 1997, 6.

‘‘Passages: Melbourne E. Bay.’’ Clavier. Vol. 36, No. 6, July

1997, 33.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

President John F. Kennedy’s sanctioning of the Bay of Pigs

operation had a significant impact on contemporary popular percep-

tions of his administration. For the majority, Kennedy’s actions

proved that he was willing to actively confront the perceived ‘‘com-

munist threat’’ in Central and South America. However, his action

also disillusioned student radicals who had supported Kennedy

during his election campaign and accelerated the politicization of

student protest in the United States.

In the early hours of April 17, 1961, a force consisting of 1400

Cuban exiles landed at the Bay of Pigs, Cuba, in an attempt to

overthrow the revolutionary government headed by Fidel Castro.

From the beginning, this ‘‘invasion’’ was marred by poor planning

and poor execution. The force, which had been secretly trained and

armed in Guatemala by the United States Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA), was too large to engage in effective covert operations, yet too

small to realistically challenge Castro in a military confrontation

without additional support from the United States. Most significantly,

the popular uprising upon which the invasion plan had been predicat-

ed did not occur. After three days of fighting, the insurgent force,

which was running short of ammunition and other supplies, had been

effectively subdued by Castro’s forces. In a futile effort to avoid

capture, the insurgents dispersed into the Zapata swamp and along the

coast. Cuban forces quickly rounded up 1,189 prisoners, while a few

escaped to waiting U.S. ships; 114 were killed.

Although the Bay of Pigs operation had initially been intended to

be carried out in a manner that would allow America to deny

involvement, it was readily apparent that the United States govern-

ment was largely responsible for the invasion. Months before the Bay

of Pigs operation commenced, American newspapers ran stories

which revealed the supposedly covert training operations both in

Miami and Guatemala. Consequently, when the invasion began, the

official cover story that it was a spontaneous insurrection led by

defecting Cuban forces was quickly discredited. Revelations con-

cerning the United States’ role in the attack served to weaken its

stature in Latin America and significantly undermined its foreign

policy position. After the collapse of the operation, a New York Times

columnist commented that the invasion made the United States look

like ‘‘fools to our friends, rascals to our enemies, and incompetents to

the rest.’’ However, domestic political protest was allayed by Presi-

dent John F. Kennedy who, although he had been in office for less

than one hundred days, assumed full responsibility for the fiasco.

According to Kennedy biographer Theodore C. Sorensen, Kennedy’s

decisive action avoided uncontrolled leaks and eliminated the possi-

bility of partisan investigations.

The operation which resulted in the Bay of Pigs disaster had

initially been conceived in January 1960 under the Eisenhower

Administration. Originally, this operation was envisioned as consti-

tuting the covert landing of a small, highly-trained force that would

engage in guerrilla activities in order to facilitate a popular uprising.

Over the ensuing fifteen months, the CIA systematically increased the

scale of the proposed operation. According to both Sorensen and

biographer Arthur M. Schlesinger, Kennedy, upon assuming office,

had little choice but to approve the continuance of the operation. Its

importance had been stressed by former president Dwight D. Eisen-

hower, it was supported by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and by influential

advisors such as John Foster Dulles. Further, as noted historian

John L. Gaddis argued in Now We Know: Rethinking Cold War

History (1997), Kennedy believed that ‘‘underlying historical forces

gave Marxism-Leninism the advantage in the ’third world’’’ and

viewed Cuba as a clear example of the threat that Communism posed

in Latin America. As a result, Kennedy was predisposed to take action

against Castro. Unfortunately, due to inaccurate and ineffective

communication between planning and operational personnel, the

significant changes that had been instituted within the operation were

not sufficiently emphasized to Kennedy. Consequently, according to

Sorensen, Kennedy ‘‘had in fact approved a plan bearing little

resemblance to what he thought he had approved.’’ Leaders of the

Cuban exiles were given the impression that they would receive direct

military support once they had established a beach head, and an

underlying assumption of CIA planning was that the United States

would inevitably intervene. However, Kennedy steadfastly refused to

sanction overt military involvement.

The impact of the Bay of Pigs invasion on American public

opinion was sharply divided. According to Thomas C. Reeves,

Kennedy’s public support of and sympathy for the Cuban exiles

rallied the public in support of their ‘‘firm, courageous, self-critical,

and compassionate chief executive.’’ A poll conducted in early May

indicated sixty-five percent support for Kennedy and his actions.

Conversely, the Bay of Pigs invasion also served to spark student

protests. Initially, students had been enchanted by Kennedy’s vision

of a transformed American society and by the idealism embodied by

programs such as the Peace Corps. However, students, particularly

those within the New Left, were disillusioned by Kennedy’s involve-

ment with the invasion. On the day of the landings, 1,000 students held

a protest rally at Berkeley, and on April 22, 2,000 students demonstrat-

ed in San Francisco’s Union Square. This disillusionment spawned a

distrust of the Kennedy Administration and undoubtedly accelerated

the political divisions that developed within American society during

the 1960s.

Internationally, the Bay of Pigs invasion provided Castro with

evidence of what he characterized as American imperialism, and this

enabled him to consolidate his position within Cuba. Ultimately, the

invasion drove Castro toward a closer alliance with the Soviet Union

BAYWATCHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

193

and significantly increased both regional and global political ten-

sions. The failure of the invasion also convinced Soviet leader Nikita

Khrushchev that Kennedy was weak and indecisive. This impression

undoubtedly contributed to Khrushchev’s decision to place nuclear

missiles in Cuba and to the confrontation that developed during the

Cuban Missile Crisis (1962). However, sympathetic biographers have

argued that ‘‘failure in Cuba in 1961 contributed to success in Cuba in

1962,’’ because the experience forced Kennedy to break with his

military advisors and, consequently, enabled him to avoid a military

clash with the Soviet Union.

—Christopher D. O’Shea

F

URTHER READING:

Bates, Stephen, and Joshua L. Rosenbloom. Kennedy and the Bay of

Pigs. Boston, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard

University, 1983.

Gaddis, John Lewis. We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History.

Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1997.

Higgins, Trumbull. The Perfect Failure: Kennedy, Eisenhower, and

the CIA at the Bay of Pigs. New York, W.W. Norton, 1987.

Lader, Lawrence. Power on the Left: American Radical Movements

Since 1946. New York, W.W. Norton, 1979.

Reeves, Thomas C. A Question of Character: A Life of John F.

Kennedy. Rocklin, California, Prima Publishing, 1992.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the

White House. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

Sorensen, Theodore C. Kennedy. New York, Harper & Row, 1965.

Vickers, George R. The Formation of the New Left: The Early Years.

Lexington, Lexington Books, 1975.

Wyden, Petre. Bay of Pigs: The Untold Story. London, Jonathan

Cape, 1979.

Baywatch

Though dismissed by its critics with such disparagements as

‘‘Body watch’’ and ‘‘Babe watch,’’ David Hasselhoff’s Baywatch

became the most popular television show in the world during the mid-

1990s. Notorious for its risque bathing suits, the show depicted the

Los Angeles County Beach Patrol as it braved dangerous surf and

emotional riptides to save lives and loves. The show ran briefly on

NBC during 1989-1990 before being canceled but became, in its new

incarnation, one of the few shows in TV history not only to exonerate

itself in a post-network afterlife but to actually become a mega-hit.

Baywatch began with David Hasselhoff as Mitch Buchannon, a

veteran career lifeguard recently promoted to lieutenant; Parker

Stevenson as Craig Pomeroy, a successful lawyer who continued to

moonlight as a lifeguard; and a supporting cast of sun-bronzed

characters who adopted life at the beach for reasons of their own. In its

original incarnation, Baywatch finished in seventy-fourth place in the

Neilsen ratings among 111 series to air on the three major networks.

At the same time, it ranked as the number-one U.S. import in both

Germany and Great Britain, where viewers perceived it to be a

glimpse of what America was all about in a format that was at once

wordless and instantly translatable to any culture in the world—

beautiful people in a beautiful environment.

In 1990, after being canceled by the network, Baywatch star

Hasselhoff and three of the show’s other producers recognized its

international potential and decided to invest their own money in the

show. They cut production costs from $1.3 million per episode to

$850,000, and marketed it to independent stations. In syndication, the

show generated more than one billion viewers between 1994 and

1996 in more than one hundred countries around the world.

‘‘We wanted to create a dramatic series that allows our lead

characters to become involved with interesting and unusual people

and situations,’’ said executive producer Michael Berk. ‘‘Lifeguards

are frequently involved in life and death situations and, as a part of

their daily routine, come into contact with thousands of people from

diverse walks of life.’’ This format allows the lifeguards to interact

with an amazing number of robbers, murderers, international drug

runners, runaway teens, and rapists who seemingly stalk L.A.’s

beaches between daring rescues, shark attacks, and boat sinkings. All

of this is blended with the predictable love stories and plenty of

exposed skin. Indeed, the show’s opening, depicting the physically

perfect male and female lifeguards running on the beach, has become

one of the most satirized motifs on television.

Surprisingly, however, the soap-opera-type stories have allowed

the characters to grow from episode to episode and have created some

interesting dimensions for the show’s regulars. Hasselhoff’s charac-

ter, Mitch, comes off a nasty divorce and custody battle for his son and

begins to date again. ‘‘He’s a guy about my age,’’ says Hasselhoff

(forty), ‘‘divorced, with a kid. With many years as a lifeguard under

his belt, he’s promoted to lieutenant and must take on a more

supervisory role. But, he has mixed emotions. He is no longer one of

the guys and must assume the role of an authority figure, while at

home, as a newly divorced parent, he has to learn to cope with the

responsibilities of a single father.’’

The other characters on the show have been significantly young-

er, with the average cast member being in his or her twenties. Each

succeeding season has brought new cast members to the series as

older characters drifted off, died in accidents, married, and otherwise

moved on as the stars who played them became famous enough to

move into other acting ventures. Pamela Anderson Lee, the former

‘‘Tool Time’’ girl’’ on Home Improvement, left Baywatch after

becoming an international sex symbol and garnered a movie contract,

only to be replaced by a succession of similarly endowed sun-

drenched California blondes.

The reasons for the show’s phenomenal success are varied.

Many critics have argued that the sex appeal of the lifeguards in their

scanty beach attire has been the primary reason for viewers (particu-

larly young males) to tune in. Baywatch has, in fact, created its share

of sex symbols with Hasselhoff, Lee, and, more recently, Yasmine

Bleeth and Carmen Electra achieving international celebrity on

tabloid covers and calendars. There is also the appeal of the beach

itself and the California lifestyle—a sun-and-surf image that offers an

escape from the grim reality of people’s daily existence. Some say

there is a more fundamental appeal that is as old as television itself:

Baywatch is a family ensemble no less than The Waltons, Little House

on the Prairie or Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman. Hasselhoff’s Mitch is

the father figure for the group of lifeguards, while his female

counterpart, Lt. Stephanie Holden (Alexandra Paul), serves as a

surrogate mother for the beach people who wander in and out of each

BAZOOKA JOE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

194

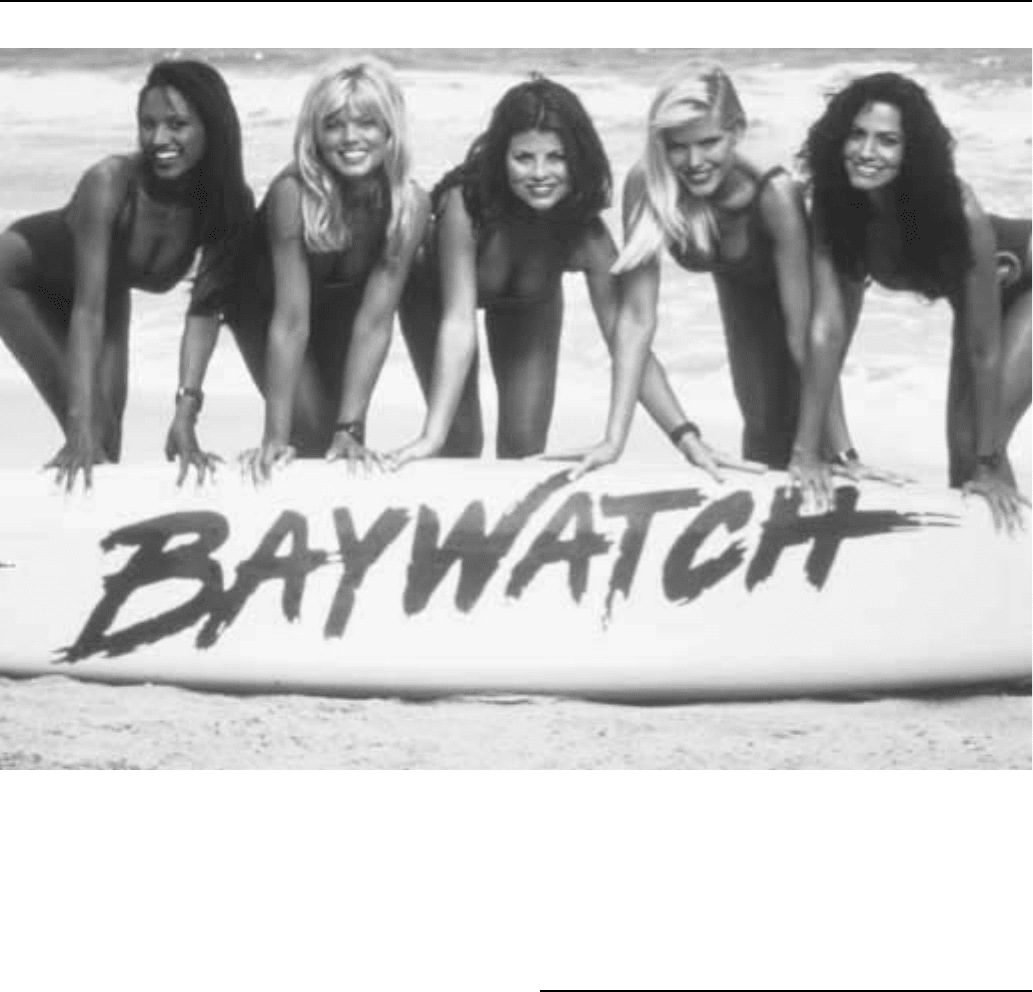

The women of Baywatch.

episode (until the Holden character’s death during the seventh sea-

son). The supporting cast of lifeguards are the quirky and quarreling

siblings who ultimately must be rescued from their various escapades

by Hasselhoff’s character. Then there is Mitch’s own son, Hobie, a

thirteen-year-old who gets into his own adventures and who is just

beginning to get to know his father. The two-part ending of the

1997-98 season featured Mitch’s marriage to Neely Capshaw (Gena

Lee Nolen).

In an effort to attract the whole family rather than its earlier self-

professed teenager demographic, Baywatch gradually escalated the

level of its story lines to include depictions of social ills, acceptance of

aging and death, and a number of ethical and moral dilemmas. ‘‘What

has happened,’’ said Hasselhoff, ‘‘is that while people were making

so many jokes about us, we became a real show.’’

—Steve Hanson

F

URTHER READING:

Baber, Brendan, and Eric Spitznagel. Planet Baywatch. New York,

St. Martin’s Griffin, 1996.

Hollywood Reporter Baywatch Salute. January 17, 1995, 99.

McDougal, Dennis. ‘‘TV’s Guilty Pleasures: Baywatch.’’ TV Guide.

August 13, 1994, 12.

Shapiro, Marc. Baywatch: The Official Scrapbook. New York, Boule-

vard Books, 1996.

Bazooka Joe

Gum manufacturers commonly used gimmicks, like sports trad-

ing cards, to help boost sales. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., which began

producing Bazooka bubble gum in 1947, included comics with its

small chunk of pink bubble gum. The gum took its name from the

unplayable musical instrument, which American comedian Bob Burns

made from two gas pipes and a whiskey funnel, called a ‘‘bazooka.’’

The comic, featuring Joe, a blonde kid with an eye patch, and his

gang, debuted in 1953. In the crowded chewing gum market of the

1950s, Topps used the comic to distinguish Bazooka from other

brands. The jokes produced more groaning than laughter, and includ-

ed a fortune. Collectors of the comics redeemed them for prizes, such

as bracelets, harmonicas, and sunglasses. In the 1990s, Joe’s populari-

ty fell, and the strip was modernized in response to market studies in

which kids said they wanted characters who were ‘‘more hip.’’

—Daryl Umberger

BEACH BOYSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

195

FURTHER READING:

Wardlaw, Lee. Bubblemania: A Chewy History of Bubble Gum. New

York, Aladdin, 1997.

The Beach Boys

As long as bleach-blond beach bums ride the waves and lonely

geeks fantasize of romance, the Beach Boys will blare from car radios

into America’s psyche. Emerging from Southern California in the

early 1960s, the Beach Boys became the quintessential American teen

band, their innocent songs of youthful longing, lust, and liberation

coming to define the very essence of white, suburban teenage life. At

the same time, they mythologized that life through the sun-kissed

prism of Southern California’s palm trees, beaches, and hot rods,

much like the civic boosters and Hollywood moguls who preceded

them. From 1962 to 1966, the Beach Boys joined Phil Spector and

Berry Gordy as the most influential shapers of the American Top 40.

But like the California myth itself, the Beach Boys’ sunny dreams

were tempered by an underlying darkness, born of their tempestuous

personal and professional lives. That darkness sometimes fueled the

group’s greatest work. It also produced tragedy for the band’s

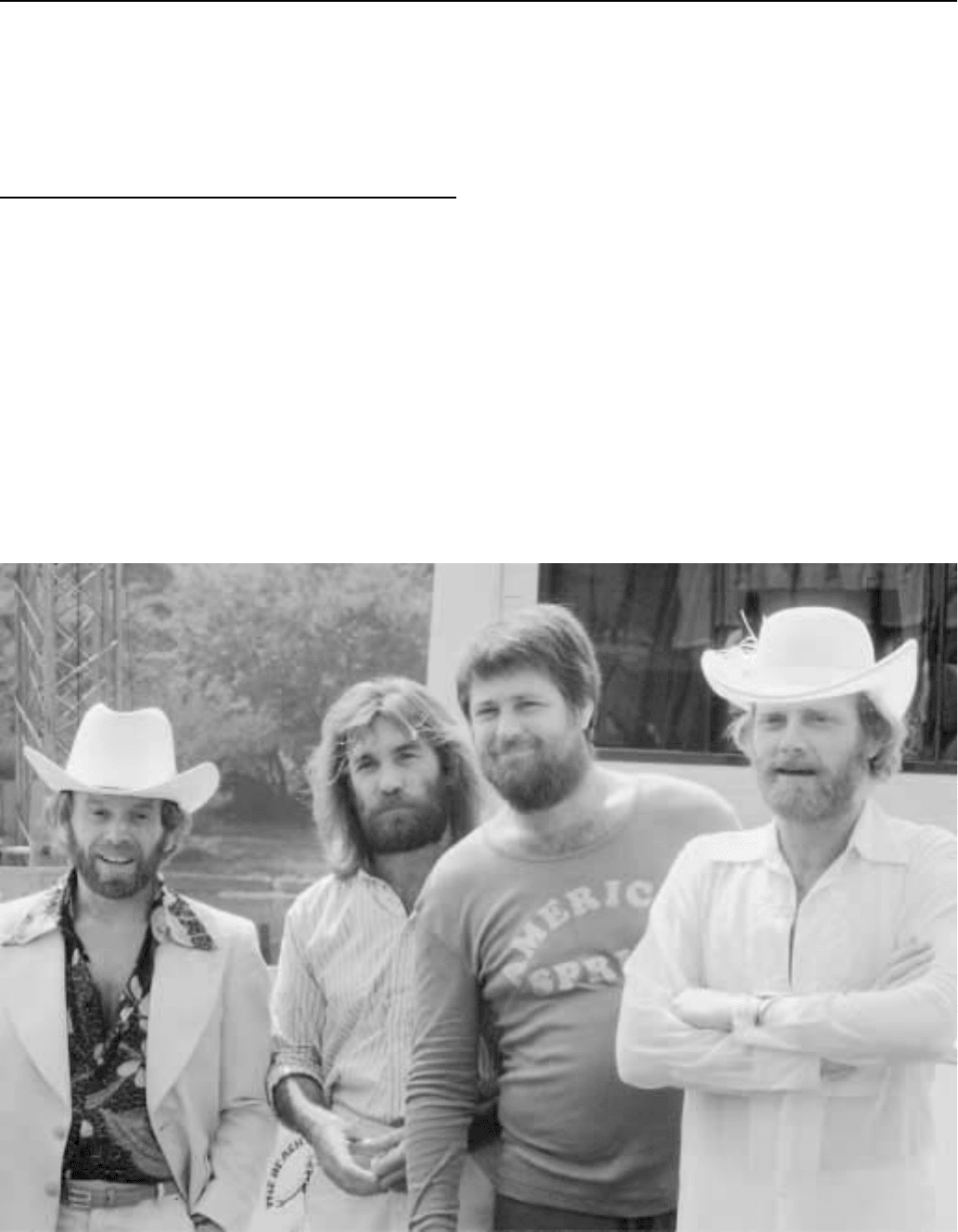

The Beach Boys

members, especially resident genius Brian Wilson, and by the 1980s

the band collapsed into self-parody.

The nucleus of the Beach Boys was the Wilson family, which

lived in a simple bungalow in the Los Angeles suburb of Hawthorne.

At home, brothers Brian (1942—), Dennis (1944-1983), and Carl

(1946-1998) were introduced to music by their temperamental father,

Murry Wilson, whose rare displays of affection were usually accom-

panied by the purchase of musical instruments, records, or lessons.

Although each son adopted his father’s love of music, it was the

eldest, Brian Wilson, who embraced it with passion. His two earliest

childhood memories were central to his musical evolution and future

career. As a toddler, Brian remembered requesting George Gersh-

win’s ‘‘Rhapsody in Blue’’ whenever he visited his grandmother’s

home. He also remembered his father slapping him at the age of three;

he blamed the loss of hearing in his right ear in grade school on the

incident. Brian was left unable to hear music in stereo for the rest of

his life.

As the Wilsons entered high school, they absorbed the music and

culture which would later fuel the Beach Boys. In addition to his

classical training at school, Brian loved vocal groups (especially the

close-harmony style of the Four Freshmen) and the complex ballads

of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley. But the Wilsons—even the reclusive

Brian—were also immersed in the teenage culture of suburban

BEACH BOYS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

196

America: hot rods, go-karts, drive-ins, and, most importantly, rock ’n’

roll. They listened to Bill Haley and Elvis Presley and above all

Chuck Berry, whom guitarist Carl Wilson idolized. By high school

the boys were playing and writing songs together.

In 1961, the group expanded beyond Carl’s improving guitar,

Brian’s accomplished bass, and Dennis’ primitive drums. The Wilsons’

cousin Mike Love (1941—), a star high school athlete with an

excellent voice, joined on vocals. Brian’s friend from school, Al

Jardine (1942—), rounded out the band after aborting a folk-singing

career. With that, America’s most famous suburban garage band was

born, at first hardly able to play but hungry for the money and fame

that might follow a hit record.

Their sound came first, mixing the guitar of Chuck Berry and

backbeat of rhythm and blues with Brian’s beloved vocal harmonies.

But they knew they lacked an angle, some theme to define the band’s

image. They found that angle one day when Dennis Wilson, sitting on

the beach, got the idea to do a song about surfing. By the early 1960s,

the surf craze in Southern California had already spawned the ‘‘surf

music’’ of artists like Dick Dale and the Del-Tones, based around the

crashing guitar sounds intended to mimic the sound of waves. Surf

music, however, was just beginning to enter the national conscious-

ness. With prodding, Dennis convinced Brian that there was lyrical

and musical potential in the surf scene, and in September of 1961 they

recorded ‘‘Surfin’’’ as the Pendeltones, a play on the name of Dale’s

band and in honor of the Pendleton shirts favored by beach bums. By

December, the single had climbed the national charts, and the band

renamed itself the Beach Boys.

In 1962 Capitol Records signed them, and over the next three

years the Beach Boys became a hit machine, churning out nine Top 40

albums and 15 Top 40 singles, ten of which entered the top ten. In

songs like ‘‘Surfin’ U.S.A.,’’ ‘‘Little Deuce Coupe,’’ and ‘‘Fun, Fun,

Fun’’ the group turned Southern California’s youthful subculture into

a teenage fantasy for the rest of America and the world. A baby boom

generation hitting adolescence found exuberant symbols of their

cultural independence from adults in the band’s hot rods and surfboards.

The songs, however, articulated a tempered rebellion in acts like

driving too fast or staying out too late, while avoiding the stronger

sexual and racial suggestiveness of predecessors like Presley or

successors like the Rolling Stones. In their all-American slacks and

short-sleeve striped shirts, the Beach Boys were equally welcome in

teen hangouts and suburban America’s living rooms.

By 1963, the Beach Boys emerged as international stars and

established their place in America’s cultural life. But tensions be-

tween the band’s chief songwriter, Brian Wilson, and the band’s fan-

base emerged just as quickly. Wilson was uninterested in his audi-

ence, driven instead to compete obsessively for pop preeminence

against his competitors, especially Phil Spector and later the Beatles.

To make matters worse, Wilson was a shy introvert, more interested

in songwriting and record production than the limelight and the stage.

He retreated into the studio, abandoning the proven style of his

earliest hits for Spector’s wall-of-sound sophistication on songs like

‘‘Don’t Worry Baby’’ and ‘‘I Get Around.’’ At the same time,

Wilson’s personal melancholia increasingly entered his songwriting,

most notably on the monumental ballad ‘‘In My Room.’’ Together,

these changes altered the Beach Boys’ public persona. ‘‘I Get

Around’’ was a number one single in 1964, but ‘‘Don’t Worry

Baby,’’ arguably the most creative song Wilson had yet written,

stalled ominously at number 24. And ‘‘In My Room,’’ while unques-

tionably about teenagers, deserted innocent fun for painful longing. It

also topped out at number 23. The Beach Boys were growing up, and

so was their audience. Unlike Wilson, however, the post-teen boomers

already longed nostalgically for the past and struggled to engage the

band’s changes.

The audience was also turning elsewhere. The emergence of the

Beatles in 1964 shook the foundations of the Beach Boys camp.

Suddenly supplanted at the top of the pop charts, the rest of the band

pushed Brian Wilson toward more recognizably ‘‘Beach Boys’’

songs, which he wisely rebuffed considering rock ’n’ roll’s rapid

evolution during the mid-1960s. In addition, the entire band began

living out the adolescent fantasies they had heretofore only sung

about. Only now, as rich young adults, those fantasies meshed with

the emerging counter-culture, mysticism, and heavy drug use of the

late-1960s Southern Californian music scene. With the rest of the

band tuning out, Wilson’s Beatles obsession and drug abuse acceler-

ated, Beach Boys albums grew more experimental, and Wilson

suffered a nervous breakdown.

For two years after Wilson’s breakdown, the Beach Boys’ music

miraculously remained as strong as ever. ‘‘Help Me, Rhonda’’ and

‘‘California Girls’’ (both 1965) were smash hits, and the live album

The Beach Boys Party! proved the band retained some of its boyish

charm. But no Beach Boys fan—or even the Beach Boys them-

selves—could have been prepared for Brian Wilson’s unveiling of

Pet Sounds (1966), a tremendous album with a legacy that far

outshines its initial success. Completed by Brian Wilson and lyricist

Tony Asher, with only vocal help from the other Beach Boys, Pet

Sounds was Brian Wilson’s most ambitious work, a dispiriting album

about a young man facing adulthood and the pain of failed relation-

ships. It also reflected the transformation of Southern California’s

youth culture from innocence to introspection—and excess—as the

baby boomers got older. Moreover, Pet Sounds’ lush pastiche pushed

the boundaries of rock so far that no less than Paul McCartney hailed

it as his favorite album ever and claimed it inspired the Beatles to

produce Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. In subsequent

decades, some critics would hail Pet Sounds as the greatest rock

album ever made, and it cemented the Beach Boys’ place in the

pantheon of popular music. At the time, however, critics in the United

States had already dismissed the band, and their fans, accustomed to

beach-party ditties, failed to understand the album. Although two

singles—‘‘Sloop John B’’ and ‘‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice’’— entered the

top ten, sales of the album fell below expectations.

Disappointed and increasingly disoriented, Wilson was deter-

mined to top himself again, and set to work on what would become the

most famous still-born in rock history, Smile (1967). Intended to

supplant Pet Sounds in grandeur, the Smile sessions instead collapsed

as Wilson, fried on LSD, delusional, and abandoned by the rest of the

group, was unable to finish the album. Fragments emerged over the

years, on other albums and bootlegs, that suggested the germ of a

great album. All that survived in completed form at the time,

however, was one single, the brilliant number one hit ‘‘Good

Vibrations,’’ which Smile engineer Chuck Britz said took three

months to produce and ‘‘was [Brian Wilson’s] whole life’s perform-

ance in one track.’’

If Britz was right then Wilson’s timing could not have been

better, for short on the heels of the failed Smile sessions came the

release of Sgt. Pepper. As if he knew that his time had passed, Wilson,

like his idol Spector, withdrew except for occasional Beach Boys

collaborations, lost in a world of bad drugs and worse friends until

the 1990s.

The Beach Boys carried on, occasionally producing decent

albums like Wild Honey (1967), at least one more classic song,

BEACHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

197

Brian’s 1971 ‘‘’Til I Die,’’ but their days as a cultural and commercial

powerhouse were behind them. In 1974, with the release of the

greatest-hits package Endless Summer, the band finally succumbed to

the wishes of its fans (and at least some of its members), who

preferred celebrating their mythic land of teenage innocence the

Beach Boys had so fabulously fabricated in their early years. The

album shot to number one, spending 155 weeks on Billboard’s Hot

100, and the quintessential American teen band now remade itself as

the quintessential American oldies act. They traveled the country well

into the 1990s with beach party-styled concerts, performing their

standards thousands of times. In 1983, Interior Secretary James Watt

denied them permission to play their annual July 4 concert in

Washington, D.C. to maintain a more ‘‘family-oriented’’ show.

Miraculously, they scored one more number one single with

‘‘Kokomo,’’ a kitschy 1988 track intended to play on their nostalgic

image. Along the way, they endured countless drug addictions, staff

changes, inter-group lawsuits over song credits, and two deaths—

Dennis Wilson in a 1981 drowning and Carl Wilson of cancer in 1998.

That some of the Beach Boys’ early music perhaps sounds

ordinary 30 years later owes something to the group’s descent into

self-parody. But it also reflects the degree to which their music

infiltrated American culture. No artists better articulated California’s

mythic allure or adolescence’s tortured energy. And when that allure

and energy was lost, their music paved the road for the journeys later

musicians—from the Doors to the Eagles and Hole—would take into

the dark side of the Californian, and American, dream.

—Alexander Shashko

F

URTHER READING:

Hoskyns, Barney. Waiting for the Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes,

and the Sound of Los Angeles. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

White, Timothy. The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the

Beach Boys, and the Southern California Experience. New York,

Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1994.

Wilson, Brian, with Todd Gold. Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Own Story.

New York, Bloomsbury Press, 1986.

Beach, Rex (1877-1949)

‘‘Big hairy stories about big hairy men’’ is how one critic

described the work of one of the early twentieth century’s most

prolific and successful popular writers, Rex Beach. He developed

a devoted following among the reading public which remained

loyal to his works into the mid-1930s. In addition, he led the way

for later authors to reap greater profits by exploiting other me-

dia outlets for their works, thus defining what the twentieth-cen-

tury author of popular literature became by mid-century—an

independent entrepreneur.

Rex Ellingwood Beach was born in Atwater, Michigan, in 1877.

At age twelve his family packed their belongings and sailed by raft

down the Mississippi and across the Gulf of Mexico to Florida, where

they took up residence on homesteaded land. Beach attended Rollins

College at Winter Park but left shortly before graduation to move to

Chicago. He read law in an older brother’s law office and took one or

two law courses, but he never finished a law program. Afflicted with

gold fever after reading of the vast gold discoveries in the far north,

Beach headed for Alaska in 1897 to seek his fortune. He found little

gold. Instead he discovered wealth of a different kind, a mine of

stories and colorful characters and situations that he developed into

best selling popular literature.

In the summer of 1900, Beach witnessed a bold attempt by North

Dakota political boss Alexander McKenzie to steal gold from the

placer mines at Nome, Alaska. When the scheme failed, McKenzie

and his cronies were arrested. Beach transformed the events into a

series of muckraking articles, ‘‘The Looting of Alaska,’’ for Apple-

ton’s Century magazine in 1905. From this series came his first novel,

The Spoilers. He added some fictional characters to the events at

Nome, and the resulting novel, published in 1905, made the best-

seller list in 1906. Later that year he transformed the novel into a play,

which ran for two-week runs in Chicago and New York before it was

sent out on the road for several years. In 1914 Beach contracted with

the Selig Corporation to release the film version of The Spoilers for 25

percent of the gross profits, a unique arrangement for its time. On four

subsequent occasions, in 1923, 1930, 1942, and 1955, Beach or his

estate leased the rights to The Spoilers to film companies for the same

financial arrangement. Beach published a total of twenty novels and

seventy short stories and novelettes. He authorized thirty-two film

adaptations of his work. In addition to The Spoilers, The Barrier was

filmed three times; five of his novels were filmed twice; and fourteeen

of his novels and stories were each filmed once.

Writing in the school of realism, his novels and stories were

works of romantic, frontier adventure aimed at young men. Plots

involved ordinary hard-working citizens forced to confront the forces

of nature and corruption. They overcame their adversaries by means

of violence, loyalty to the cause and to each other, and heroic action.

Rarely did these citizens rely on government agencies for assistance,

in keeping with Beach’s philosophy of rugged individualism.

From 1911 to 1918 Beach was president of the Author’s League.

In this capacity he constantly exhorted authors to put film clauses into

their publishing contracts and to transform their writings into drama

and screenplays. Most refused, believing that the cinema was a low art

form that degraded their artistic endeavors. The only exception was

Edna Ferber, who also demanded a percentage of the profits for

filming her works. On the occasions that novels and short stories were

adapted, the one-time payments that authors received to film their

works were small, varying greatly from film company to film

company. In frustration, Beach resigned the position in 1918 and

concentrated on writing until the mid-1930s.

From his wandering search for gold and stories in Alaska to his

unique film clause in his contract with Harper Brothers to his

pioneering lease arrangement with film corporations, he established

precedents that others would follow years later and that define

popular authors after mid-century. He not only had an innate sense of

what people would read, but also, ever alert to other potential media

markets, he knew what people would pay to see as thrilling entertain-

ment on stage and on film. Above all, Beach had a formidable passion

for financial success. He viewed his mind as a creative factory

producing a marketable product. Writing involved raw material,

production, and sales. The end result was profit.

Not content with his literary and entertainment achievements,

Beach used his profits to buy a seven-thousand-acre estate in Florida

where he became a successful cattle rancher in the 1930s. He wrote

articles about the nutritional value of growing crops in mineral-rich

BEANIE BABIES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

198

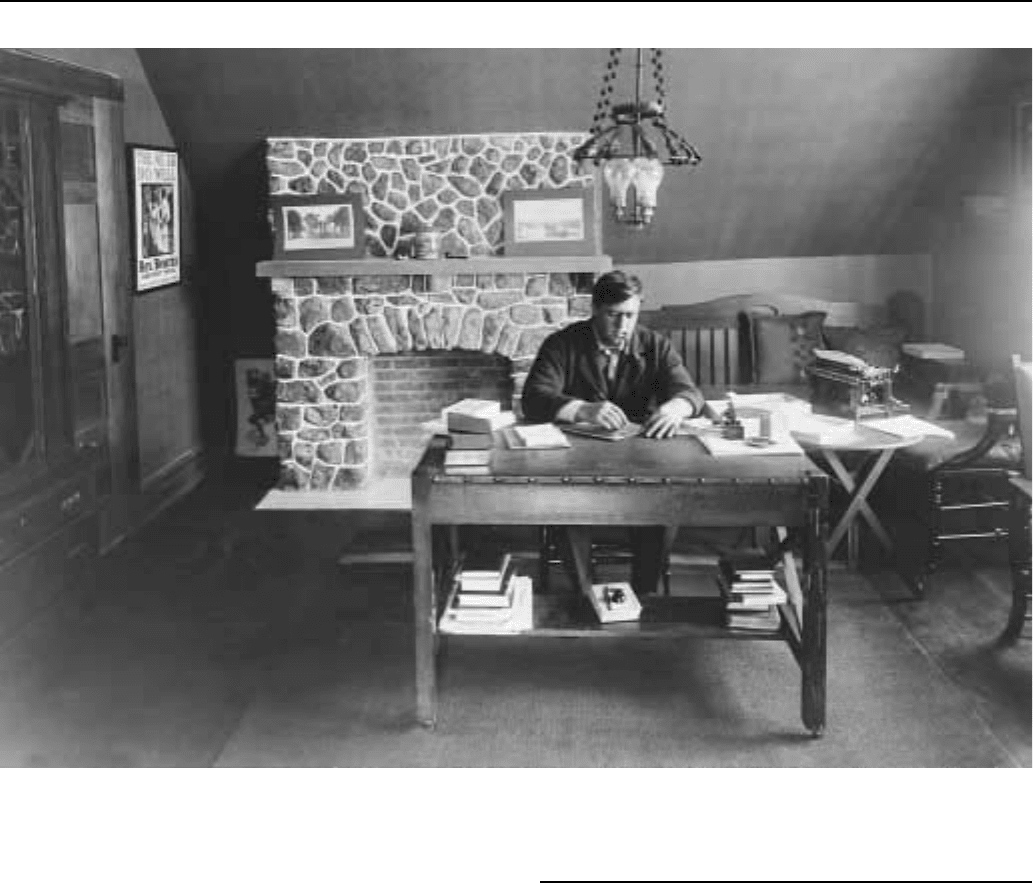

Rex Beach

soils. He bought an additional two thousand acres at Avon Park and

grew gladioli and Easter lilies at substantial profit. In the 1940s he

developed and wrote more than forty episodes of an unproduced radio

series based on his autobiography, Personal Exposures.

Beach sold everything he wrote, except for the radio series and

an unfinished novel that he was writing at the time of his death. He

and his wife, Edith Greta Crater, divided their time between a New

York penthouse and their 250-acre estate in Sebring, Florida. His

wife, whom he had met in Alaska and married in 1907, died in 1947

after a lengthy illness. On the morning of December 7, 1949,

saddened by his wife’s death, nearly blind, and devastated by the pain

and other effects of throat cancer, Rex Beach ended his life with a

pistol shot to the head. He was seventy-two.

—James R. Belpedio

F

URTHER READING:

Beach, Rex. Personal Exposures. New York, Harper & Broth-

ers, 1940.

———. The Spoilers. New York, Harper & Brothers, 1905.

Belpedio, James R. ‘‘Fact, Fiction, Film: Rex Beach and The Spoil-

ers.’’ Ph.D. diss., University of North Dakota, 1995.

Beanie Babies

In 1993 Ty Corporation released Flash the Dolphin, Patti the

Platypus, Splash the Orca, Spot the Dog, Legs the Frog, Squealer the

Pig, Cubbie the Bear, Chocolate the Moose, and Pinchers the Lobster.

These small plush beanbag toys called Beanie Babies retailed for

about five dollars. By 1997, there were over 181 varieties of Beanie

Babies, and most of the original nine were worth more than $50.

The interest Beanie Babies sparked in so many kids, parents, and

collectors stems from their reflection of the consumer aesthetic of the

1990s. Ty Corporation built a cachet for each Beanie Baby by

portraying itself as one of the ‘‘little guys’’ in the toy industry. It

limited stores to only 36 of each Beanie Baby per month and initially

refused to sell to chain or outlet toy stores. Ty Corporation guarded its

strategy fiercely, cutting off future supplies to stores that sold the

plush animals at a mark-up. The company’s efforts kept Beanie

Babies affordable to almost all, but increased their aftermarket value.

The result of Ty’s strategy strengthened Beanie Babies’ celebration of

the individual. Each baby is assigned a name, a birthday, and an

accompanying poem, all found on the small heart-shaped Ty tag, the

sign of an authentic Beanie Baby.

Some regard the market frenzy around Beanie Babies as ridicu-

lous, but others see it as a benign introduction to capitalism for many