Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BEANIE BABIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

199

young investors. The babies are portable, easily saved for investment

purposes, and offer a chance for friendly competition between collec-

tors. Judging a Beanie Baby’s current value can be a hands-on lesson

in supply and demand for the young collector. The value of Babies

increases when varieties are ‘‘retired’’ or produced in limited num-

bers; and when custom Beanie Babies are released for sporting

events, to commemorate the flags of certain countries, and to immor-

talize celebrities like Jerry Garcia (see Garcia bear) and Princess

Diana (see Princess bear). In addition, Babies with defects or odd

materials are highly sought-after. Because it is never clear how many

of a new animal will be produced or when they might be retired,

hobby collectors and Beanie Baby speculators periodically swarm

stores reported to be ‘‘connected.’’

The market demand for Beanie Babies has grown without

television advertising. Babies were listed as one of the most sought-

after Christmas toys by several stores during the 1990s. Beanie

Babies are traded, bought, and sold at hundreds of spots on the

Internet, and those new to the hobby can buy guidebooks like the 1998

Beanie Baby Handbook, which lists probable prices for the year 2008.

A McDonald’s employee displays some of the Beanie Babies the restaurant sold in 1998.

The Handbook speculates that Quacker, a yellow duck with no wings,

may be worth as much as $6,000 by that time.

Beanie Babies have worked their way into the mainstream

consciousness through a regular media diet of Beanie Baby hysteria

and hoax stories. Many local news programs would feature a story

about how to differentiate between a real Beanie Baby and a fake. By

the end of the decade, almost every American would see the sign,

‘‘Beanie Babies Here!’’ appear in the window of a local card or

flower shop. Established firmly in the same collectible tradition as

Hot Wheels cars and Cabbage Patch dolls, Beanie Babies draw

children into the world of capitalist competition, investment, and

financial risk. Their simple, attainable nature has gained them a

permanent place in the pantheon of American toys.

—Colby Vargas

F

URTHER READING:

Fox, Les and Sue. The Beanie Baby Handbook. New York, Scholastic

Press, 1998.

BEASTIE BOYS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

200

Phillips, Beck, et al. Beanie Mania: A Comprehensive Collector’s

Guide. Binghamton, New York, Dinomates, 1997.

The Beastie Boys

In 1986 the Beastie Boys took the popular music world by storm

with their debut album License To Ill and the single ‘‘Fight For Your

Right (To Party).’’ The album was co-produced with fledgling hip-

hop label Def Jam producer Rick Rubin. License to Ill became the

fastest selling debut album in Columbia Records’ history, going

platinum within two months, and becoming the first rap album to

reach number one on the charts.

Critics derided the Beastie Boys as one-hit wonder material, and

as New York ‘‘white-boy rappers’’ who were leeching off African

American street music forms known as ‘‘rap’’ and hip-hop, both of

which were in their early stages of development. Licensed To Ill also

relied heavily on a new technique called ‘‘sampling.’’ Sampling is the

act of lifting all or part of the music from another artist’s song. This

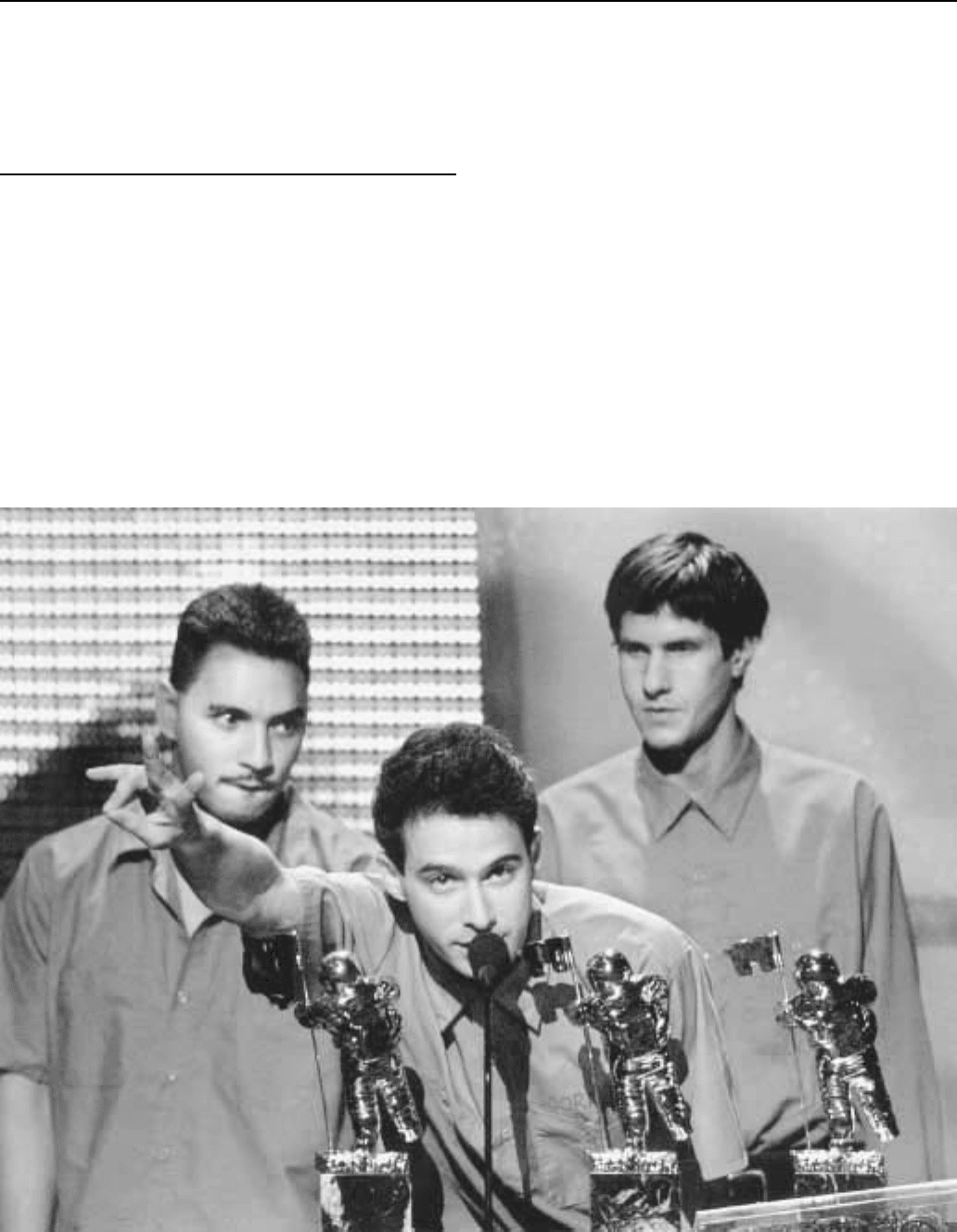

The Beastie Boys, from left: Adam Yauch (MCA), Adam Horovitz (King Ad-Rock), and Mike Diamond (Mike D) at the MTV video awards.

sample is then used to record a new song with the same music, often

without credit or payment. Sampling, as it was originally practiced,

was condemned as stealing by most critics and musicians. The

technique was so new in the mid-1980s that there were no rules to

regulate such ‘‘borrowing.’’ Artist credit and payment terms for use

of a sample, however, eventually became the record industry standard.

Michael Diamond (‘‘Mike D’’), bassist Adam Yauch (‘‘MCA,’’

also known as Nathanial Hornblower), guitarist John Berry, and

drummer Kate Schellenbach formed the first version of The Beastie

Boys in New York City in 1981. They were a hardcore punk style

band and recorded the EP Polywog Stew on a local independent label.

Eventually, Berry and Schellenbach quit. In 1983 Adam Horovitz

(‘‘Ad-Rock’’) joined Mike D and MCA to form the core of the

Beastie Boys. Other musicians have been added to the onstage mix

and toured with the Beastie Boys throughout their career, but it is this

trio that is the creative and musical force behind the band.

It was at this time that Rick Rubin, a New York University

student and Def Jam’s record label entrepreneur, took notice of the

Beastie Boys’ rap inspired underground single hit ‘‘Cookie Puss.’’

Rubin and the Boys then recorded ‘‘Rock Hard’’ for Def Jam in 1985.

Later that year the Beastie Boys received enough attention from a

BEAT GENERATIONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

201

soundtrack cut, ‘‘She’s On It,’’ to earn an opening spot on Madonna’s

‘‘Like A Virgin’’ tour, and then they went on tour with Run D.M.C.

In 1986 License To Ill was released, and despite their commer-

cial success, the Beastie Boys were derided as sophomoric, sexist, and

just plain dumb. After a long tour to promote License To Ill, the

Beastie Boys left Def Jam for Capitol Records. The Beastie Boys

moved to Los Angeles, took a break, and then began to examine their

sound and style. They now had the task of following up their

incredible success with a new album. They worked with a new

production team known as the Dust Brothers, and in 1989 the Beastie

Boys released Paul’s Boutique. The album was critically acclaimed,

but completely different from License To Ill and sold under a

million copies.

After two more albums with Capitol Records, Check Your Head

in 1992 and Some Old Bullshit in 1994, the Beastie Boys launched

their own record label called Grand Royal. Their first Grand Royal

release came in 1994. Ill Communication spawned the single ‘‘Sabo-

tage,’’ and the group toured with the yearly Lollapalooza alternative

festival that summer.

Adam Yauch’s conversion to Buddhism and his ties to the Dalai

Lama then prompted the Beastie Boys to organize the Tibetan

Freedom Festival in the summer of 1996. Popular artists continue to

donate their performances in order to raise money for the Miarepa

Fund, a charity that supports ‘‘universal compassion through music’’

and has been active in the fight for Tibetan independence.

In 1998 the Beastie Boys released Hello Nasty. In the midst of

personal business and charity efforts, the Beastie Boys have contin-

ued to push the cutting edge of hip-hop and they have gained a

respected place in the alternative music scene of the 1990s.

—Margaret E. Burns

F

URTHER READING:

Batey, Angus. The Beastie Boys. New York, Music Sales Corpora-

tion, 1998.

Beat Generation

The Beat Generation, or ‘‘Beats,’’ is a term used to describe the

vanguard of a movement that swept through American culture after

World War II as a counterweight to the suburban conformity and

organization-man model that dominated the period, especially during

the Eisenhower years (1953-1961), when Cold War tension was

adding a unparalleled uptightness to American life. The term ‘‘Beat

Generation’’ was apparently coined by Jack Kerouac, whose 1957

picaresque novel On the Road is considered a kind of manifesto for

the movement. In 1952, John Clellon Holmes wrote in the New York

Times Magazine: ‘‘It was John Kerouac . . . who several years ago . . .

said ‘You know, this is really a beat generation . . . More than the

feeling of weariness, it implies the feeling of having been used, of

being raw.’’’ Holmes used the term in his 1952 novel Go, with

obvious references to New York’s bohemian scene. The claim,

advanced in some circles, that Kerouac intended ‘‘beat’’ to be related

to ‘‘beatific’’ or ‘‘beatitude’’ is now considered spurious by

etymologists, though Beatitude was the name of a San Francisco

magazine published by poet Allen Ginsberg and others whose folding

in 1960 is regarded as the final chapter in that city’s Beat movement

(generally known as the San Francisco Renaissance).

Kerouac penned a dictionary definition of his own that charac-

terized Beats as espousing ‘‘mystical detachment and relaxation of

social and sexual tensions,’’ terms that clearly include those at the

literary epicenter of the Beat movement, such as Allen Ginsberg,

Gregory Corso, John Clellon Holmes, William Burroughs, Neal

Cassady, and Herbert Huncke, the latter an alienated denizen of

Times Square who served as an important guide to the nascent

movement. Each of these figures embodied creative brilliance with

various combinations of psychotic episodes, unconventional sexuali-

ty, or antisocial traits. Later additions included Lawrence Ferlinghetti,

Diane di Prima, and many others. They, along with the writers who

were drawn to the experimental Black Mountain College in North

Carolina—or, like the expatriate Burroughs, to drug-soaked residen-

cy in Tangiers—carried forward an essentially Blakean and Whitmanian

vision that welcomed spontaneity, surrealism, and a certain degree of

decadence in poetic expression and personal behavior. In the 1950s,

this put them in opposition to the prevailing currents of literary

modernism on the model of T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, and the

middlebrow poetry of Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg. Poetry, like

Ginsberg’s ‘‘Howl’’ or Corso’s Gasoline series, was the favored

genre of expression and the ‘‘3-Ms’’—marijuana, morphine, and

mescaline—were the drugs of choice.

William Carlos Williams enthusiastically took on the role of

unofficial mentor to the East-Coast Beat poets after meeting Allen

Ginsberg, and Kenneth Rexroth has been described as the ‘‘godfather

of the Beats’’ for acting as catalyst to the famous reading at the Six

Gallery in San Francisco, where on October 13, 1955, Ginsberg

offered his first highly dramatic performance-recital of ‘‘Howl.’’

Nearby was Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore, which

served as both shrine and paperback publisher for the literature of the

Beat movement through its familiar black-and-white ‘‘Pocket Poet’’

series. Following the reading, Lawrence Ferlinghetti approached

Ginsberg and convinced him to publish a chapbook of ‘‘Howl’’

through City Lights Press in San Francisco. In 1957, Howl and Other

Poems was seized by customs officials, and Ferlinghetti was tried on

charges of obscenity. The trial brought great notoriety and worldwide

recognition to the message of Beat poetry, and the book’s sales

skyrocketed after the charges were dropped.

In general terms, the Beat poets were leftist in political orienta-

tion and committed to the preservation of the planet and the human

species. Their literature speaks out against injustice, apathy, consum-

erism, and war. Despite such generalizations, however, at an indi-

vidual level the poets are very difficult to classify. A highly diverse

group, their political and spiritual views varied to extremes: Jack

Kerouac and Gregory Corso, for example, supported the war in

Vietnam; Allen Ginsberg was a Jewish radical and anarchist; and

Philip Whalen was ordained a Zen priest. The difficulty of pinning

down the essence of the Beat poets is part of their allure. The Beats

earned their defiant image in part through the controversial themes in

their work, which included celebration of the erotic, sexual freedom,

exploration of Eastern thought, and the use of psychedelic substances.

Fred McDarrah’s Time magazine article offers evidence of how they

were unkindly characterized in mainstream media: ‘‘The bearded,

sandaled beat likes to be with his own kind, to riffle through his

quarterlies, write craggy poetry, paint crusty pictures and pursue his

never ending quest for the ultimate in sex and protest.’’ Such

condescending judgments only served to fuel the fascination with the

Beat image among younger people.

BEAT GENERATION ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

202

Though the most well-known of the Beat poets are white males,

the movement was not exclusively so. In contrast with many other

literary movements, the Beats were tolerant of diversity and counted

many women and poets of color among their ranks. Such poets as Ted

Joans, Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), and Bob Kaufman were recog-

nized by their peers for the importance of their work. The women of

the Beat Generation, including Diane di Prima, Joanne Kyger, Anne

Waldman, and many others, were as present if not as visible as the

men. As Brenda Knight remarked, ‘‘the women of the Beat Genera-

tion, with rare exception, escaped the eye of the camera; they stayed

underground, writing. They were instrumental in the literary legacy of

the Beat Generation, however, and continue to be some of its most

prolific writers.’’

Though many readers have been attracted to the work of the

Beats by their cultural image, Anne Waldman contends that their

durability stems from their varied and kaleidoscopic use of language.

Beat poets abandoned traditional forms, syntax, and vocabulary in

order to incorporate new rhythms, hip streetwise slang, and inventive

imagery into their work. In her introduction to The Beat Book,

Waldman describes this style as ‘‘candid American speech rhythms,

jazz rhythms, boxcar rhythms, industrial rhythms, rhapsody, skillful

cut-up juxtapositions, and an expansiveness that mirrors the primor-

dial chaos.... This is writing that thumbs its nose at self-serving

complacency.’’ Though their style constituted a break from tradition-

al forms, the Beats always acknowledged the contributions of their

precursors. Poets of the early twentieth century such as William

Carlos Williams and the imagists H.D. and Ezra Pound paved the way

for them by loosening the constraints around poetic language.

When Kerouac and Holmes published articles in the 1950s using

the term ‘‘Beat generation’’ to describe their cultural milieu, it was

picked up by the mainstream media and solidified in popular culture.

‘‘Beat’’ in popular parlance meant being broke, exhausted, having no

place to sleep, being streetwise, being hip. At a deeper level, as John

Clellon Holmes wrote in his 1952 article, ‘‘beat . . . involves a sort of

nakedness of mind, and, ultimately, of soul; a feeling of being reduced

to the bedrock of consciousness.’’ With increased usage of the term in

the media, ‘‘Beat’’ came to signify the literary and political expres-

sion of the artists of the 1940s and 1950s.

The term ‘‘beatnik’’ has thus been rather generously applied to

describe any devotee of the 1950s angst-ridden countercultural life-

style, ranging from serious Beat intellectuals like Jack Kerouac,

William Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg to the more ‘‘cool cat’’

bongo-drumming pot-smoking denizens of coffee houses—males in

beards and females in leotards—who ‘‘dug it’’ in such far flung

bohemian outposts as New York’s Greenwich Village and Venice,

California. Strictly speaking, ‘‘beatnik’’ was a term invented by the

popular press only toward the end of the decade, after the launch of

the Russian Sputnik satellite in the fall of 1957 spawned a host of ‘‘-

nik’’ words in popular lingo on the model of already existing Yiddish

slang words like nudnik. Herb Caen, a columnist for the San Francis-

co Chronicle, coined the term ‘‘beatnik’’ in an article he wrote for the

paper on April 2, 1958, though the Oxford English Dictionary records

the first use of the word in a Daily Express article that July 23,

describing San Francisco as ‘‘the home and the haunt of America’s

Beat generation . . . the Beatniks—or new barbarians.’’

Whatever its origins, it is clear that during 1958, the word

‘‘beatnik’’ suddenly began appearing in magazines and newspapers

around the world as a catchall phrase to cover most forms of urban,

intellectual eccentrics, sometimes used in tandem with the dismissive

‘‘sicknik.’’ It is also clear that few average Americans came into

contact with self-avowing beatniks except by reading about them

under the ‘‘Manners and Morals’’ heading in Time magazine or, more

likely, through the rather stereotypical character of Maynard G.

Krebs, who appeared on the CBS series The Many Loves of Dobie

Gillis from 1959 to 1963. Krebs was described by Charles Panati in

his 1991 book Panati’s Parade of Fads, Follies, and Manias as a

figure who ‘‘dressed shabbily, shunned work, and prefaced his every

remark with the word like. ‘‘ A decade earlier, however, a poetry-

spouting proto-beatnik character named Waldo Benny had appeared

regularly on The Life of Riley television sitcom, though he was never

named as such.

Arguably the most definitive study of beatniks and the Beat

Movement is Steven Watson’s 1995 book The Birth of the Beat

Generation: Visionaries, Rebels, and Hipsters, in which he describes

the Beats as exemplifying ‘‘a pivotal paradigm in twentieth-century

American literature, finding the highest spirituality among the mar-

ginal and the dispossessed, establishing the links between art and

pathology, and seeking truth in visions, dreams, and other nonrational

states.’’ Watson and other cultural historians see the Beats as cultural

antecedents to later countercultural groups that included Ken Kesey’s

Merry Pranksters and hippies in the 1960s and punks in the 1970s.

Reflecting on his own earlier participation in the Beat Movement,

Robert Creeley wrote in the afterword of the 1998 paperback version

of Watson’s book that being Beat was ‘‘a way of thinking the world,

of opening into it, and it finally melds with all that cares about life, no

matter it will seem at times to be bent on its own destruction,’’ and

closed with the lines by Walt Whitman used as the motto for ‘‘Howl’’:

‘‘Unscrew the locks from the doors!/Unscrew the doors themselves

from their jambs!’’

—Edward Moran and Caitlin L. Gannon

F

URTHER READING:

Bartlett, Lee. The Beats: Essays in Criticism. Jefferson, N.C., Lon-

don, McFarland, 1981.

Cassaday, Neal. The First Third and Other Writings. San Francisco,

City Light Books, 1971, 1981.

Foster, Edward Halsey. Understanding the Beats. Columbia, S.C.

University of South Carolina Press, 1992.

Ginsberg, Allen. Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco, City Light

Books, 1956.

Huncke, Herbert. Guilty of Everything. New York, Paragon

House, 1990.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. New York, Viking, 1957.

———. Selected Letters, 1940-1956. Edited by Ann Charters. New

York, Viking, 1955.

Kherdian, David, editor. Beat Voices: An Anthology of Beat Poetry.

New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1995.

Knight, Brenda. Women of the Beat Generation: The Writers, Artists,

and Muses at the Heart of a Revolution. Berkeley, California,

Conari Press, 1996.

Panati, Charles. Panati’s Parade of Fads, Follies, and Manias. New

York, HarperCollins, 1992.

Watson, Steven. The Birth of the Beat Generation: Visionaries,

Rebels, and Hipsters. New York, Pantheon, 1995.

BEATLESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

203

The Beatles

Emerging out of the Liverpool, England, rock scene of the

1950s, the Beatles became the most successful and best known band

of the twentieth century. In 1956, a Liverpool local named John

Lennon formed the Quarrymen. At one of their first performances,

John met another guitarist, Paul McCartney. The two hit it off

immediately: Paul was impressed by John’s energetic performance,

and John was impressed that Paul knew how to tune a guitar, knew

more than three chords, and could memorize lyrics. John and Paul

developed a close friendship based on their enthusiasm for rock’n’roll,

their ambition to go ‘‘to the toppermost of the poppermost,’’ and a

creative rivalry which drove them to constant improvement and

experimentation. The pair soon recruited Paul’s friend George Harri-

son to play lead guitar and nabbed a friend of John’s, Stu Sutcliffe, to

play the bass (though he did not know how). The Quarrymen,

eventually renamed the Beatles, developed a local reputation for their

rousing, exuberant performances and the appeal of their vocals. John

and Paul were both excellent singers; Paul had a phenomenal range

and versatility, while John had an uncanny ability to convey emotion

through his voice. The sweetness and clarity of Paul’s voice was ideal

for tender love songs, while John specialized in larynx-wrenching

rockers like ‘‘Twist and Shout.’’ Their voices complemented each

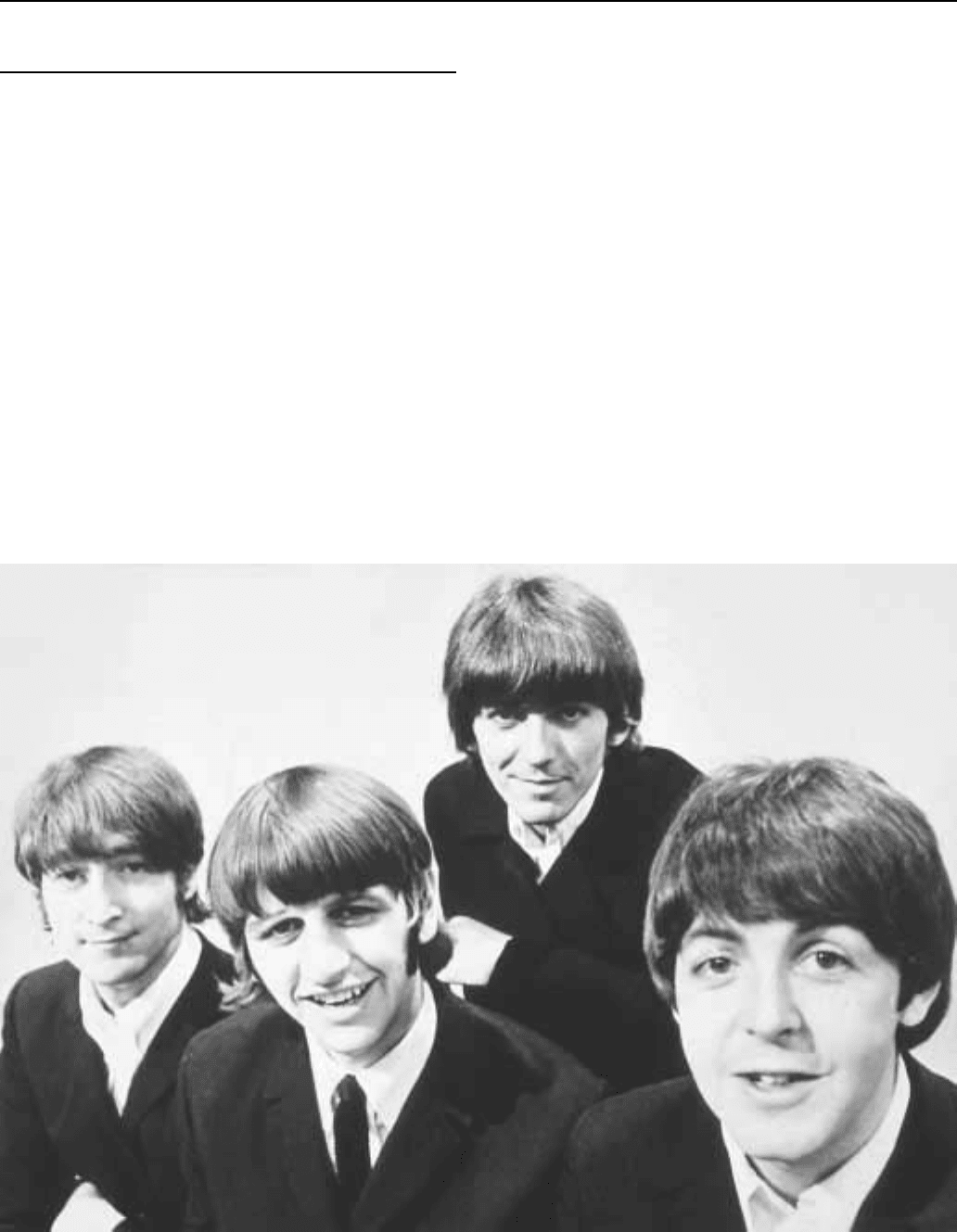

The Beatles, from left: John Lennon, Ringo Starr, George Harrison, and Paul McCartney.

other perfectly, both in unison and in harmony, and each enriched his

own style by imitating the other. The inexplicable alchemy of their

voices is one of the most appealing features of the Beatles’ music.

In 1960 the band members recruited drummer Pete Best for a

four-month engagement in Hamburg, Germany, where they perfected

their stage act. In 1961, Sutcliffe quit the band, and Paul took up the

bass, eager to distinguish himself from the other two guitarists. The

Beatles procured a manager, Brian Epstein, who shared their convic-

tion that they would become ‘‘bigger than Elvis.’’ After many

attempts to get a recording contract, they secured an audition with

producer George Martin in July, 1962. Martin, who liked their

performance and was charmed by their humor and group chemistry,

offered the Beatles a contract, but requested that they abandon Pete

Best for studio work, whom he found musically unsuitable to the

group chemistry. The Beatles gladly consented, and recruited Ringo

Starr, whom they had befriended in Hamburg. Their first single—

‘‘Love Me Do’’ (released October, 1962)—reached number 17 on the

British charts. Their next single, ‘‘Please Please Me’’ (January,

1963), hit number one. Delighted with their success, they recorded

their first album, Please Please Me (March, 1963), and it too reached

the top of the charts.

In those days, rock albums were made to cash in on the success

of a hit single, and were padded with filler material, usually covers of

BEATLES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

204

other people’s songs. If the artists had any more decent material, it

was saved for the next single. However, the Beatles included eight

Lennon-McCartney originals, along with six cover songs from their

stage repertoire on their debut album. This generosity marked the

beginning of the album as the primary forum of rock music, displac-

ing the single, and setting a new standard of quality and originality.

Please Please Me may sound less impressive today, but it was far

superior to the average rock album of 1963. The opening track, ‘‘I

Saw Her Standing There,’’ was a revelation, a rousing, energetic

rocker teeming with hormonal energy. (Released in America as

Introducing the Beatles, the album didn’t sell well.)

Their third single, ‘‘From Me To You’’ (April, 1963), also hit

number one in England, but it was their fourth, ‘‘She Loves You’’

(August, 1963), which brought ‘‘Beatlemania’’—the name given to

the wild form of excitement which the Beatles elicited from their

fans—to a fever pitch around the world. Most of the Beatles’ lyrics

during this period were inane—the ‘‘yeah yeah yeah’’ of ‘‘She Loves

You’’ being perhaps the silliest—but when delivered with the Beatles’

delirious enthusiasm, they worked. Real Beatlemania seems to have

begun in late 1963 (the term was coined in a London paper’s concert

review in October). Their second album, With the Beatles (Novem-

ber, 1963), was similar to the first, with six cover songs and eight

originals. The American release of ‘‘She Loves You’’ in January

1964 ignited Beatlemania there, and the group’s first appearance on

the Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964, was viewed by an

estimated 73 million people.

The phenomenon of Beatlemania wasn’t just a matter of scream-

ing girls; the madness took many forms. A music critic for the London

Times declared the Beatles ‘‘the greatest composers since Beetho-

ven,’’ and another detected ‘‘Aeolian cadences’’ in ‘‘Not a Second

Time,’’ though none of the Beatles knew what these were. Beatlemania

often seemed divorced from the music itself: everything from dolls to

dinner trays bore the likeness of the Fab Four, who had by now

become the most recognized faces in the world. Grown businessmen

would wear Beatlesque ‘‘moptop’’ wigs to work on Wall Street. Soon

the franchise led to film with A Hard Day’s Night, a comedy which

spotlighted the Beatles’ charm and humor as much as their music. The

soundtrack—released in July, 1964—was the best album of the

Beatles’ early phase. Side one contained the songs from the movie,

and side two provided six more hits. It was their first album of all

original material, an unheard of accomplishment in rock music.

Unfortunately, Capitol Records ripped off American fans by includ-

ing only the songs from the movie on their version of the soundtrack,

and filled the rest of the album with instrumental versions of those

same songs. The Beatles’ popularity was so great at this point that

American fans were willing to pay full price for albums that barely

lasted a half hour. The first seven British albums were diluted into ten

American albums by offering ten songs each instead of the usual

thirteen or fourteen. (The situation was not rectified until the advent

of the CD, when the British versions were finally released in America.)

The group’s fourth album, Beatles For Sale (December, 1964),

reverted to the earlier formula of originals songs mixed with covers. It

was the weakest album of their career to date, but was still better than

most pop albums of 1964, and hit number one. The album is important

for John’s improved lyrical efforts, beginning what he later called his

‘‘Dylan period.’’ The Beatles had met Bob Dylan earlier that year,

and he had introduced them to marijuana. John was impressed by

Dylan’s lyrics and decided to improve his own. The first tentative

effort was the introspective ‘‘I’m a Loser.’’ Help! (August 1965)—

the soundtrack for their second movie—introduced the folkish ‘‘You’ve

Got to Hide Your Love Away’’ and Paul’s acoustic ‘‘I’ve Just Seen a

Face.’’ Help! was also important for its expanded instrumentation,

including flute and electric piano.

As the Beatles grew as composers, they became more receptive

to producer Martin’s sophistication. Martin had studied music theory,

composition, and orchestration, and encouraged the Beatles to ‘‘think

symphonically.’’ A breakthrough in their collaboration with Martin

came with ‘‘Yesterday.’’ Paul had written it two years before, but had

held it back since the song was incongruous with the band’s sound and

image. By 1965, the Beatles and the world were ready, and Paul’s

lovely guitar/vocal composition, graced with Martin’s string arrange-

ment, dazzled both Beatlemaniacs and their parents with its beauty

and sophistication, and became one of the most popular songs in

the world.

Their craftsmanship and experimentation reached new heights

on Rubber Soul, one of their greatest albums. They returned to the all-

original format of A Hard Day’s Night (henceforth all of their albums

featured entirely original material, with the exception of Let It Be,

which included the sailor’s ditty, ‘‘Maggie Mae’’). John dabbled in

social commentary with ‘‘Nowhere Man,’’ a critique of conformity

reminiscent of Dylan’s ‘‘Ballad of a Thin Man.’’ But John’s song

avoided Dylanesque superciliousness through his empathy with the

character. John began to master understatement and poetic suggestion

in the enigmatic ‘‘Norwegian Wood.’’ This was also the first song to

feature George’s sitar. George had discovered the sitar while filming

Help! and had been turned on to Indian music by the Byrds. The Byrds

contributed to the artistry of Rubber Soul by providing the Beatles

with serious competition on their own debut album earlier that year.

Hailed as the American Beatles, the Byrds were the only American

band who attained a comparable level of craftsmanship and commer-

cial appeal without simply imitating the Beatles. Before then, the

Beatles’ only serious competitors were the Rolling Stones. Soon

competitors would rise all around the Beatles like rivals to the throne.

But the Beatles kept ahead, constantly growing and expanding,

experimenting with fuzz bass, harmonium, and various recording

effects. The most impressive thing about Rubber Soul was that such

innovation and sophistication were achieved without any loss of the

exuberance and inspiration that electrified their earlier albums. It was

an impressive union of pop enthusiasm and artistic perfection. Few

would have guessed that the Beatles could surpass such a triumph—

but they did.

Their next album, Revolver (August, 1966), is widely regarded

as the Beatles’ masterpiece, and some consider it the greatest album

ever made, featuring fourteen flawless compositions. George’s

‘‘Taxman’’ was the hardest rock song on the album, featuring a

blistering, eastern-sounding guitar solo reminiscent of the Yardbirds’

‘‘Heart Full of Soul’’ and the Byrds’ ‘‘Eight Miles High.’’ But

George’s masterpiece was ‘‘Love You To.’’ He had previously used

the sitar to add an exotic coloring to songs, but here he built the entire

composition around the sitar, and expressed his growing immersion

in Eastern spirituality. John was even spacier in the acid-drenched

‘‘She Said She Said’’ and ‘‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’’ full of

backwards-recorded guitar, tape loops, and countless studio effects to

enhance the mind-boggling lyrics. John, George, and Ringo had

experimented with LSD by this time, and John and George were

tripping regularly and importing their visions into their music. (Paul

did not sample LSD until February 1967). Paul’s experiments were

more conventional, but equally rewarding. He followed up the

achievement of ‘‘Yesterday’’ with the beautiful ‘‘Eleanor Rigby.’’

The poignant lyrics marked the beginning of Paul’s knack for creating

BEATLESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

205

vivid character portraits in a few deft verses. ‘‘Here, There, and

Everywhere’’ was another beauty, containing the sweetest vocal of

Paul’s career, and the bright, bouncing melody of ‘‘Good Day

Sunshine’’ showed Paul’s increasing sophistication on the bass.

Revolver set a new standard in rock music, and became the master-

piece against which all subsequent albums were measured.

The achievement of Revolver was due partially to the Beatles’

decision to stop performing concerts after the current tour, which

would free their music from the restrictions of live performability.

They played their last concert on August 29, 1966, without playing

any songs from the new album. Exhausted, they withdrew from public

life, took a brief break, then began work on a new album. The silence

between Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band lasted

ten months—the longest interval between albums thus far, but ended

with a stunning single, ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever‘‘/‘‘Penny Lane,’’

which revealed the growing individuality of the composers’ styles.

John was visionary, introspective, and cryptic in ‘‘Strawberry Fields

Forever;’’ while Paul was sentimental, suburban, and witty in ‘‘Penny

Lane.’’ John was abstract, questioning his role in the human riddle;

Paul was concrete, using odd little details to bring his characters to

life. The two songs complemented each other perfectly, and hinted at

the variegated brilliance of the album to come.

Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band (June, 1967) has

been hailed as the quintessential album of the sixties, and especially

of the famous Summer of Love of 1967. It was the most esoteric and

ambitious work ever attempted. To enumerate its charms, innova-

tions, and influence would fill volumes, but special mention must be

made of ‘‘A Day in the Life,’’ one of the last great Lennon-

McCartney collaborations, and one of the most hauntingly beautiful

songs of their careers. Weaving together the story of a wealthy heir

who dies in a car crash, an estimate of potholes in Blackburn,

Lancashire, and a vignette of a young man on his way to work, the

song is an ironic montage of the quotidian and the universal, sleeping

and waking, complacency and consciousness, establishment and

counterculture, and an orgasmic union of high and low art, all rolled

into one five-minute, three-second song.

Although ‘‘A Day in the Life’’ is the highlight of a bold,

brilliant, stunning album, Sgt. Pepper is probably not the Beatles’

greatest work, and has not aged as well as Revolver. If Revolver is a

14-course meal which delights, satisfies, and nourishes, Sgt. Pepper is

an extravagant dessert for surfeited guests—overrich, decadent, fat-

tening. Lavish and baroque, it did not maintain the energetic, youthful

exuberance that shines through the complexities of Revolver. Many

will agree with Martin’s judgment that Revolver is the Beatles’ best

album, while Sgt. Pepper is their most significant work. It was also

the last truly influential work by the Beatles. Although they continued

to evolve and experiment, they would no longer monopolize centerstage,

for 1967 saw a trend toward instrumental virtuosity and improvisation

led by Cream and Jimi Hendrix.

The Beatles’ next project, Magical Mystery Tour (December,

1967), coasted along on the plateau established by Sgt. Pepper.

Magical Mystery Tour was a pointless film following the Beatles on a

bus trip around England. Paul got the idea from the Merry Pranksters,

a counterculture group traveling across America. The film was a flop,

and the Beatles’ first real failure. The soundtrack featured a mix of

good and mediocre songs, but some recent singles gathered onto side

two strengthened the album.

In 1968 the Beatles went to India to study meditation with

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, during which they learned of Epstein’s

death from an overdose of sleeping pills. Eventually disenchanted

with the Maharishi, the Beatles returned with a potpourri of songs.

They proposed to release a double album to accommodate the

abundance. Martin was unimpressed with the material however, and

recommended releasing a potent single album like Revolver. But the

rivalry among the band members was so intense that all four Beatles

favored the double album to get their songs included. The result was

one of the Beatles’ strangest albums, The Beatles (November, 1968).

The blank white cover and simple title reflected the minimalist nature

of much of the material, which had been composed on acoustic guitars

in India. Most of the 30 songs were individual efforts, often sung and

played solo. McCartney played every instrument on some of his

songs. The bewildering array of styles seemed like a history (or

perhaps a parody) of western music.

Yellow Submarine was a cartoon made to fulfill the Beatles’ film

contract with United Artists (although Let It Be would actually fulfill

this obligation a year later). The Beatles were not interested in the

project, and contributed several older, unused songs to the soundtrack.

The cartoon was entertaining, but the album Yellow Submarine

(January, 1969) is the biggest ripoff of the Beatles’ catalog, featuring

only four original songs. Side two was padded with Martin’s orches-

tral soundtrack. Still, Lennon’s great rock song ‘‘Hey Bulldog’’

makes the album a must-have.

These odd albums of the late 1960s marked the beginning of the

end of the Beatles. Musically, their individual styles were drifting

apart, but the real sources of strife were more mundane. First, they had

difficulty in agreeing on a manager to replace Epstein. Secondly, John

had become smitten with avant-garde artist Yoko Ono, and insisted

on bringing her into the Abbey Road Studios with him. Paul, too, had

married and the creative core of the group began to feel the need to

have a family life. This caused tension because as a band the Beatles

had always been an inviolable unit, forbidding outsiders to intrude

upon their creative process. But John had invited Yoko to recording

sessions simply because he wanted to be constantly by her side. The

tensions mounted so high that Ringo and George each briefly quit the

band. These ill-feelings persisted on their next project, another

McCartney-driven plan to film the Beatles, this time while at work in

the studio. The documentary of their creative process (released the

following year as Let It Be) was all the more awkward because of the

tensions within the band. Martin became fed up with their bickering

and quit, and the ‘‘Get Back’’ project was indefinitely canned.

Eventually Paul persuaded Martin to return, and the Beatles

produced Abbey Road (September, 1969), one of their best-selling

and all-time favorite albums. They once again aimed to ‘‘get back’’ to

rock’n’roll, and recovered the enthusiasm and spontaneity of their

pre-Pepper period, producing a solid performance that stood up to

Revolver. George outdid himself with two of the greatest composi-

tions of his career, ‘‘Something’’ and ‘‘Here Comes the Sun.’’ The

main attraction of the album was the suite of interconnected songs on

side two, culminating in the Beatles’ only released jam session, a

raunchy guitar stomp between Paul, George, and John. It was a

brilliant ending to a brilliant album. Unfortunately, it was also the end

of the Beatles as well, for the band broke up in June, 1970, due to

insurmountable conflicts. Producer Phil Spector was summoned to

salvage the ‘‘Get Back’’ project. He added lavish strings and horns to

the patched-together recordings, and it was released as Let It Be (May,

1970) along with a film of the same name. Somewhat of an anticlimax

after the perfection of Abbey Road, and marred by Spector’s suffocat-

ing production, it was nevertheless a fine collection of songs, made all

the more poignant by alternating moods of regret and resignation in

Paul’s songs, ‘‘Two of Us’’ and ‘‘Let It Be.’’

BEATTY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

206

Her Majesty the Queen inducted the Beatles as Members of the

British Order on October 26, 1965. This was not only the climax of

Beatlemania, but a symbolic moment in history, bridging the realms

of high and low culture. The other great honor of the Beatles’ career

was the invitation to appear on the world’s first global broadcast, on

June 25, 1967. The Beatles wrote ‘‘All You Need Is Love’’ for the

occasion, and played it live for an estimated 350 million viewers. It is

remarkable that they were allowed to represent England for the world

when Paul had announced a week earlier that he had taken LSD, the

BBC had recently banned radio play of ‘‘A Day in the Life,’’ and the

whole world was scouring Sgt. Pepper for subversive messages.

These two honors reveal the Beatles as unifiers, not dividers. One of

their greatest achievements was to resonate across boundaries and

appeal to multiple generations and classes, to represent the counter-

culture while winning the respect of the establishment. Although they

started as tough, leatherclad teddy boys, they achieved much more by

working within the mainstream, creating rather than tearing down,

combining meticulous skill with daring innovation. This was achieved

by a blessed union: the reckless irreverence of John Lennon and the

diplomacy, dedication, and craftsmanship of Paul McCartney.

—Douglas Cooke

F

URTHER READING:

Hertsgaard, Mark. A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the

Beatles. New York, Delacorte Press, 1995.

MacDonald, Ian. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and

the Sixties. New York, Henry Holt, 1994.

Martin, George, and Jeremy Hornsby. All You Need Is Ears. London,

MacMillan, 1979.

Norman, Philip. Shout! The Beatles in Their Generation. New York,

Warner Books, 1982.

Robertson, John, with Chris Charlesworth, editor. The Complete

Guide to the Music of the Beatles. New York, Omnibus Press, 1994.

Beatty, Warren (1937—)

One of the most extraordinarily handsome screen actors of his

generation, Warren Beatty proved remarkably sparing in exploiting

his image. That image has tended to seem contradictory, often

puzzling, to commentators and critics, but there is universal agree-

ment that no subsequent disappointments in Beatty’s work could

obscure his achievement in portraying the impotent, crippled, trigger-

happy Clyde Barrow, at once inept, ruthless, and curiously touching,

in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Brilliantly directed and photographed, with meticulous attention

paid to historical accuracy, Bonnie and Clyde was a watershed in the

then thirty-year-old Beatty’s career, for it was he who masterminded

the entire project, from buying the script to hiring director Arthur

Penn and choosing the cast. The superb production values and style of

the film which, in its fearless and poetic use of bloodshed, made it

both influential and highly controversial, stamped Warren Beatty as a

producer of flair and intelligence, and his evident ambitions might

account for the discomforting and enigmatic sense of detachment that

has robbed several of his performances of conviction.

Born Henry Warren Beaty in Richmond, Virginia, Beatty is the

younger brother of dancer and actress Shirley MacLaine. He acted in

Warren Beatty

amateur productions staged by his mother, who was a drama coach,

during childhood and later studied at Northwestern University and

with Stella Adler. A slow progression via television in New York and

a stock company took him to Broadway for the first and last time in

William Inge’s A Loss of Roses, where Beatty was seen by director

Elia Kazan. Beatty made his Hollywood debut opposite Natalie Wood

in Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass (1961), a somber, archetypically

1960s examination of teenage sexual angst and confusion, in which

the actor gave a suitably moody performance and mesmerized audi-

ences with his brooding good looks.

For the next six years Beatty gave variable (but never bad)

performances in a crop of films that ranged from the interesting

through the inconsequential to the bad. Interesting were The Roman

Spring of Mrs. Stone (1961), in which, despite a bizarre attempt at an

Italian accent, he smoldered convincingly as the gigolo providing

illusory comfort to Vivien Leigh; and Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964)

with Beatty excellent as a therapist dangerously in love with a mental

patient. The inconsequential included Promise Her Anything (1966),

a romantic comedy set in Greenwich Village and costarring Leslie

Caron. His reputation as a Don Juan was already in danger of

outstripping his reputation as a star, and when Caron left her husband,

the distinguished British theater director Peter Hall, he cited Beatty as

co-respondent in the ensuing divorce.

BEAUTY QUEENSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

207

Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965), a pretentious failure, did

nothing for Beatty, and neither did the comedy-thriller Kaleidoscope

the same year. Next came Bonnie and Clyde followed by the first of

several absences from the screen that punctuated his career over the

next thirty-five years. His reappearance as a compulsive gambler in

The Only Game in Town (1970), a film with no merit, was a severe

disappointment and indicated a surprising lack of judgment, re-

deemed by his mature performance as another kind of gambler in the

Old West in Robert Altman’s imaginative evocation of frontier town

life, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). Julie Christie was his costar and

his new headline-catching romance. In 1974 Beatty was perfectly cast

as the lone investigative journalist at the center of Alan J. Pakula’s

compelling conspiracy thriller, The Parallax View, after which he

turned producer again (and cowrote) for Shampoo (1975). A mildly

satirical tale of a hairdresser who services more than his clients’

coiffures, it was a good vehicle for Beatty’s dazzling smile and sexual

charisma, and it netted a fortune at the box office. After joining

Jack Nicholson in The Fortune—awful—the same year, Beatty

disappeared again.

He returned in 1978 with Heaven Can Wait, a surprisingly well-

received and profitable remake of Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941)

that earned four Oscar nominations. Beatty coproduced, cowrote with

Elaine May, and codirected (his first attempt) with Buck Henry, and

won the Golden Globe for best actor in a comedy before another

three-year absence. This time he came back with Reds (1981), the

high-profile undertaking that brought him serious international recog-

nition. A sprawling, ambitious epic running more than three-and-a-

half hours, Reds recounted the political activities of American Marx-

ist John Reed (Beatty) in Manhattan and Moscow, and Reed’s love

affair with Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton, the star’s new off-screen

love). The film, in which real-life characters appeared as themselves

to bear witness to events, was better in its parts than in its sum, but

there was no doubting Beatty’s seriousness of purpose as producer,

cowriter, director, and star. If his ambition had appeared to overreach

itself, he was nonetheless rewarded with both the Golden Globe and

Oscar for best director, Oscars for cinematographer Vittorio Storaro

and supporting actress Maureen Stapleton, and an impressive number

of other honors. He was thenceforth to be regarded as a heavyweight,

and his future projects were eagerly anticipated.

These expectations remained unfulfilled for seventeen years,

during which Beatty made only four films. The motive for making the

$50 million catastrophe Ishtar (1987) has remained inexplicable,

while Dick Tracy (1990), in which he directed himself as the comic-

book hero, displayed an undiminished sense of style but failed to

ignite. Bugsy (1991), about the notorious Bugsy Siegel, was slick and

entertaining although both star and film lacked the necessary edge,

but Beatty found true love at last with his costar Annette Bening and

married her. It could only have been his desire to find a romantic

vehicle for both of them that led him to such a failure of judgment as

Love Affair (1994), a redundant and poor remake of a 1939 classic,

already wonderfully remade by its creator, Leo McCarey, as An Affair

to Remember (1957).

Four years later came Bulworth (1998), a striking political satire

that reflected his own long-standing personal involvement with

politics and a canny sense of commercialism in purveying a liberal

message through a welter of bigotry. By then happily settled as a

husband and father, Warren Beatty at last demonstrated that the faith

of his admirers had not been misplaced.

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Malcolm, David. ‘‘Warren Beatty.’’ The Movie Stars Story. New

York, Crescent Books, 1986.

Parker, John. Warren Beatty: The Last Great Lover of Hollywood.

London, Headline, 1993.

Quirk, Lawrence J. The Films of Warren Beatty. New York, Citadel

Press, 1990.

Beau Geste

Beau Geste, the best selling 1924 adventure novel by Percival

Christopher Wren, has provided venerable screenplay fodder for

successive generations of Hollywood filmmakers. First adapted in a

silent version in 1926 with Ronald Colman in the title role, the

property was most memorably executed by director William Wellman in

1939. Gary Cooper starred as Michael ‘‘Beau’’ Geste, one of three

noble brothers who join the French Foreign Legion after being

wrongly implicated in a jewel theft. An Academy Award nomination

went to Brian Donlevy for his role as a villainous sergeant. A

forgettable third version appeared in 1966.

—Robert E. Schnakenberg

F

URTHER READING:

Wren, Percival Christopher. Beau Geste (Gateway Movie Classics).

Washington, D.C., Regnery Publishing, 1991.

Beauty Queens

From America’s Favorite Pre-Teen to Miss Nude World, Ameri-

ca offers a plethora of beauty contests and competitions for females,

and the occasional male, to be crowned a beauty queen. In American

Beauty, Lois Banner suggests that beauty queens illustrate the Ameri-

can ideals of social mobility and democracy: anyone can be a pageant

winner and better herself, since anyone can enter a contest. Addition-

ally, there is always another chance to win because new queens are

crowned every year.

Beauty queens are chosen for every conceivable reason. Their

role is to represent pageant sponsors as an icon and a spokesperson.

Queens represent commodities like Miss Cotton; products like Miss

Hawaiian Tropic [suntan lotion]; ethnic identity such as Miss Polish

America; festivals and fairs such as the Tournament of Roses queen;

sports like Miss Rodeo America; and geographic regions such as Miss

Palm Springs, Miss Camden County, Miss Utah-USA, Mrs. America,

and Miss World, among others. While the best known contests are for

young women, there are competitions for almost everyone from

grandmothers to babies. Specialized contests include Ms. Senior,

Miss Large Lovely Lady, and Miss Beautiful Back. Although not as

numerous, men’s contests garner entrants of different ages also.

Males can choose from the conventional masculine contests like

the International Prince Pageant or drag contests such as Miss

Camp America.

BEAUTY QUEENS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

208

Two beauty queens, c. 1959.

Early twentieth-century beauty queens were often referred to as

bathing beauties. Their outdoor contests were held in Venice, Califor-

nia, Miami Beach, Florida, and Galveston, Texas, and other beach

resorts as early as 1905. The contests were usually one of many

competitions including comic contests for men dressed like women

and contests for children. Early contenders were actresses and showgirls

as well as amateurs in their teens. Without a hierarchy of lower

contests, as there is today, to winnow down the number of participants

(there could be over 300 entrants), sponsors regularly disqualified

contestants for misrepresenting their marital status and the region

they hailed from. Early contests in the United States invited foreign

contestants, like Miss France, to vie for Queen of the Pageant or

Beauty Queen of the Universe. Among these competitions is the most

long-lived contest, the Miss America Pageant, which began in Atlan-

tic City, New Jersey in 1921.

The presentation of ethnic queens began as early as Miss

America, whose court included Miss Indian America (who did not

compete). Early ethnic contests include the Nisei Week Japanese

Festival, which started in Los Angeles in 1935, and Miss Sepia for

African American women, which began as early as 1944.

Beauty pageants and beauty queens have not always been

popular. Until the late 1940s, when Miss America gained respect

because the winners sold war bonds and won college scholarships,

beauty queens were not generally well thought of by the majority of

Americans. One congressman around 1915 wanted to create a federal

law banning beauty contests. At the time, women who exhibited their

bodies or wore makeup were considered daring, if not suspect. Other

early protesters were religious and women’s groups who issued

decrees about how contests exploited young women for the profit of

the organizers who, in almost all cases, were men. By the 1950s

beauty pageants had become status quo.

Since the 1960s protesters have become more theatrical in

showing how the contests objectify women. The Women’s Liberation

Front crowned a sheep as Miss America as part of an all day

demonstration in 1968. Students elected a cow as homecoming queen

at one college in the 1970s. In the 1980s protesters at a Miss

California contest wore costumes of baloney, skirt steak, and hot dogs.

As beauty competitions gained respect, the ideal American girl

became engraved in the American psyche. By the 1950s, when the

Miss Universe contest began, the beauty queen was at her pinnacle: a

stereotypically pretty, talented, politically conservative, WASP young

woman who was more focused on marriage than a career. The

contests floated through the 1960s until the Women’s Liberation

Movement made contestants and sponsors reflect on their values. By

the 1970s a career and self-fulfillment were added to the qualities of a

beauty queen. Well-known contests like Miss America and Miss USA

also were slowly being racially integrated. By the 1980s and 1990s

many African American women had won national titles in mixed

competitions. Contestants with disabilities that did not affect their

appearance, such as hearing impairment, were also not uncommon. In

fact, conquering an impediment such as diabetes or sexual abuse was

seen as a competition asset.

A service industry has grown up around pageantry, the term used

to describe the beauty contest phenomenon, supplying clothing,

cosmetic surgery, photography, music, jewelry, awards, makeup,

instructional books and videos, and personal trainers. While early

models and actor contestants may have had an edge on the amateurs

because of experience performing, almost all modern beauty contest-

ants train intensely to win. They take lessons on speaking, walking,

applying makeup and hairdressing, as well as studying current events.

The prizes beauty queens win have not changed much since the

1920s. Among these are public exposure, crowns, cash, savings

bonds, fur coats, jewelry, complete wardrobes, cosmetics, automo-

biles, and opportunities to model or act for television and film.

Scholarships, a relatively new prize, were introduced in the 1940s by

the Miss America Pageant. Since then, national beauty queens have

spent a year on the road—selling war bonds, appearing at shopping

center and sport event openings, and speaking to government, educa-

tional, and civic organizations such as the National Parent Teacher

Association or American Lung Association, among other duties.

State, national, and international winners like Miss USA, Miss

Universe, and Miss Arkansas make paid appearances for their pag-

eant and sponsors. National and international winners can earn over

$200,000 during their year.

—ViBrina Coronado

F

URTHER READING:

Banner, Lois. American Beauty. New York, Knopf, 1982.

Burwell, Barbara Peterson, and Polly Peterson Bowles, with fore-

word by Bob Barker. Becoming a Beauty Queen. New York,

Prentice Hall, 1987.

Cohen, Colleen Ballerino, Richard Wilk, and Beverly Stoeltje, edi-

tors. Beauty Queens on the Global Stage: Gender, Contests, and

Power. New York, Routledge, 1996.

Deford, Frank. There She Is—The Life and Times of Miss America.

New York, Viking, 1971.