Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BEN-HURENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

219

Bench, Johnny (1947—)

Known as the popular catcher for the Cincinnati Reds during the

1970s, Johnny Bench set a standard of success as perhaps the finest at

his position in modern Major League baseball. Bench first gained

national attention by winning the National League MVP (Most

Valuable Player) award in 1970 and 1972, recording ten straight Gold

Gloves, and helping Cincinnati’s ‘‘Big Red Machine’’ to World

Series victories in 1975 and 1976. Bench revolutionized his position

by popularizing a one-handed catching method that gave him greater

mobility with his throwing arm. After retiring from baseball, Bench

remained in the public spotlight through television appearances, golf

outings, and broadcasting. He is President of Johnny Bench Enter-

prises and won an Emmy for a program called The Baseball Bunch.

His success and popularity led to his induction into the Baseball Hall

of Fame in 1989.

—Nathan R. Meyer

F

URTHER READING:

Bench, Johnny, with William Brashler. Catch You Later: The Autobi-

ography of Johnny Bench. New York, Harper and Row, 1979.

Benchley, Robert (1889-1945)

In his relatively short life Benchley managed to enjoy careers as

a humorist, theater critic, newspaper columnist, screenwriter, radio

performer and movie actor. His writing appeared in such magazines

as the old Life and The New Yorker and his pieces were collected in

several books with outlandish titles. Among the film directors he

worked with were Alfred Hitchcock, Rene Clair, and Billy Wilder.

Benchley won an Academy Award for one of the comedy shorts he

wrote and starred in. Benchley was also a member in good standing of

the Algonquin Circle in Manhattan and a longtime resident of the

Garden of Allah in Hollywood. Talent runs in the Benchley family—

his grandson wrote Jaws, and both his son, Nathaniel, and his

grandson, Peter, became writers.

A genuinely funny man, it was his wit and humor that allowed

Benchley to make his way through the world and assured him his

assorted jobs. He was born in Worcester, Massachusetts and attended

Harvard. His first humor was written for The Lampoon. Settling in

New York, he got a staff job on Vanity Fair where his co-workers

included Robert E. Sherwood and Dorothy Parker. Later in the 1920s

he was hired by Life, which was a humor magazine in those days. He

wrote a great many pieces and also did the theater column. He later

said that one of the things he liked best in the world was ‘‘that 10

minutes at the theater before the curtain goes up, I always feel the way

I did when I was a kid around Christmas time.’’

The 1920s was a busy decade on Broadway and Benchley was in

attendance on the opening nights of such shows as Funny Face, Show

Boat, Dracula, Strange Interlude, and What Price Glory? In May of

1922, Abie’s Irish Rose opened and Benchley dismissed Anne Nich-

ols’ play as the worst in town, saying that its obvious Irish and Jewish

jokes must have dated back to the 1890s. Much to his surprise, the

play was a massive hit and ran for five years. Each week for Life he

had to make up a Confidential Guide with a capsule review of every

play then on Broadway. That meant he had to write something about

Abie’s Irish Rose each and every week during its run of 2,327

performances. At first he would simply note ‘‘Something awful’’ or

‘‘Among the season’s worst,’’ but then he grew more inventive and

said such things as ‘‘People laugh at this every night, which explains

why democracy can never be a success,’’ ‘‘Come on, now! A joke’s a

joke,’’ and ‘‘No worse than a bad cold.’’

At the same time that he was reviewing plays, Benchley was also

collecting his humor pieces in books. The gifted Gluyas Williams, an

old school chum from Harvard, provided the illustrations. In addition

to parodies, spoofs, and out and out nonsense pieces, some in the vein

of his idol Stephen Leacock, he also wrote a great many small essays

about himself, taking a left-handed and slightly baffled approach to

life. Only on a shelf of books by Robert Benchley is it possible to find

such titles as My Ten Years in a Quandary and How They Grew, No

Poems, or, Around the World Backwards and Sideways, and From

Bed To Worse, or, Comforting Thoughts About the Bison.

Benchley gradually drifted into the movies. He appeared in over

two dozen feature length films, including Foreign Correspondent (for

which he also wrote some of the dialogue), I Married A Witch, The

Major and the Minor (where he delivered the line about ‘‘getting out

of those wet clothes and into a dry martini’’), Take A Letter, Darling,

and The Road to Utopia. He also made nearly 50 short films. His first

one, The Treasurer’s Report, was done in 1928 for Fox. The shorts

most often took the form of deadpan lectures, giving advice on such

topics as how to read, how to take a vacation, and how to train a dog.

How To Sleep, done for Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer in the mid-1930s,

won him an Academy Award. Once in an ad in Variety he listed

himself as specializing in ‘‘Society Drunk’’ roles.

When he was working in Hollywood, Benchley most often

resided in a bungalow at the Garden of Allah, which was the favorite

lodging place of visiting actors, writers, and ‘‘hangers-on.’’ The

Garden was torn down decades ago to make way for a bank. At one

time the bank had a display of relics of the old hotel and among them

was one of Benchley’s liquor bills.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Benchley, Nathaniel. Robert Benchley, A Biography. New York,

McGraw-Hill, 1955.

Trachtenberg, Stanley, editor. American Humorists, 1800-1950. De-

troit, Gale Research Company, 1982.

Ben-Hur

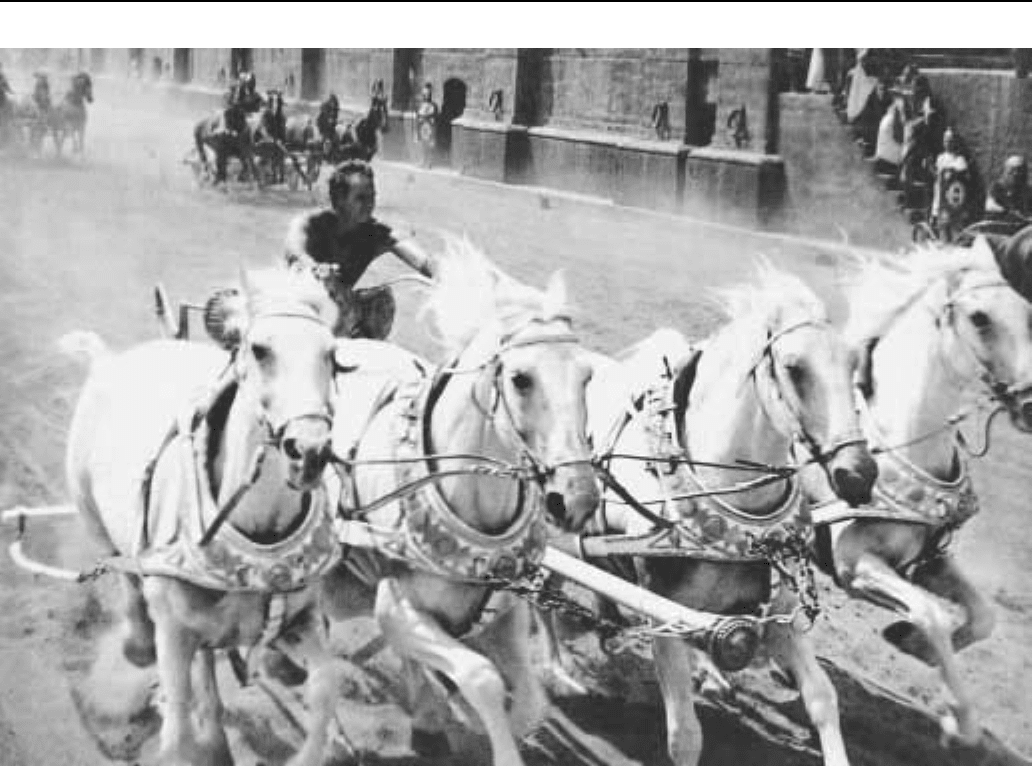

As a novel, a play, two silent films, and a wide screen spectacu-

lar, Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ set the standard for

the religious epic, inaugurating an amazing series of firsts in Ameri-

can popular culture. Published in 1880, the novel tells the story of

Judah Ben-Hur, a young, aristocratic Jew, and his encounter with

Jesus of Nazareth. The book begins with the Messiah’s birth and then

moves ahead 30 years to Ben-Hur’s reunion with his boyhood friend,

Messala, now a Roman officer. The latter’s contempt for Jews,

however, ends their friendship. When the Roman governor’s life is

threatened, Messala blames Ben-Hur, unjustly condemning him to the

galleys and imprisoning Ben-Hur’s mother and sister. As pirates

attack Ben-Hur’s ship, he manages to escape. Returning to Judea, he

BEN-HUR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

220

Charlton Heston in the chariot race from the 1959 film Ben-Hur.

searches for his family and also raises a militia for the Messiah.

Meeting Messala again, Ben-Hur beats him in a dramatic chariot race

during which the Roman is crippled. Discovering that his mother and

sister are now lepers, Ben-Hur searches for Jesus, hoping for a

miraculous cure. They finally meet on the road to Calvary. Jesus

refuses his offer of military assistance, but cures his family. Convert-

ed to Christianity, Ben-Hur resolves to help fellow Christians in

Rome suffering persecution.

The book moved slowly at first, selling only some 2,800 copies

in its first seven months. Eventually, word of mouth spread across

America, particularly through schools and clubs. By 1889, 400,000

copies had been sold, outstripping Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but falling just

short of the Bible. Sales swelled to 1,000,000 by 1911, with transla-

tions appearing in German, French, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and

Arabic, among other languages. A braille edition also was available.

For many Americans, Ben-Hur was an example of edifying reading,

the first work of fiction often allowed on their bookshelves. It was

also the first book featured in the Sears Catalogue.

Wallace, a retired Union general from Indiana and one-time

governor of the Territory of New Mexico, was quickly besieged with

offers to dramatize his work. In 1899 he settled on a production

adapted by William Young of Chicago, directed by Joseph Brooks,

and featuring later cowboy film star William S. Hart as Messala. Ben-

Hur ran on Broadway for 24 weeks and was, according to the New

York Clipper, a ‘‘triumphant success,’’ generating ‘‘enormous busi-

ness’’ and ‘‘record-breaking attendance.’’ It continued to tour nation-

ally and abroad for some 20 years, making it the first play seen by

many Americans. Ben-Hur set precedents both for an author’s control

over rights to his/her work (rejecting one offer, Wallace declared,

‘‘The savages who sell things of civilized value for glass beads live

further West than Indiana’’) and for control over the adaptation of

material. Wallace insisted, for example, that no actor would portray

Christ. Instead, the Messiah was represented by a 25,000-candle-

power shaft of light. Similarly spectacular effects—such as a wave

machine for the naval battle and, for the chariot race, actual horses and

chariots running on a treadmill before a moving panorama of the

arena—set the standard for later epic films.

A 1907 film version, produced two years after Wallace’s death

and without the copyright holders’ authorization, set a different kind

of precedent. The Wallace estate sued the film’s producers for breach

of copyright, receiving a $25,000 settlement. The case marked the

first recognition of an author’s rights in film adaptations.

In 1922, two years after the play’s last tour, the Goldwyn

company purchased the film rights to Ben-Hur. Shooting began in

Italy in 1923, inaugurating two years of difficulties, accidents, and

eventually—after the merger of Goldwyn into MGM (Metro-Goldwyn-

Meyer)—a move back to Hollywood. Additional recastings (includ-

ing Ramon Navarro as Ben-Hur) and a change of director helped

BENNETTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

221

skyrocket the production’s budget to $4,000,000. With its trials and

tribulations, then, this Ben-Hur helped set another pattern for later

epic films. More positively, on the other hand, its thrilling chariot race

changed the face of filmmaking. Following in the tracks of the stage

play, its considerable expenditure of money and horses made this

sequence a brilliant tour-de-force that established the lavish produc-

tion values now associated with the Hollywood epic. Although

audiences flocked to Ben-Hur after its premiere in 1925 and critics

praised the film (more for its ‘‘grandeur,’’ however, than its story),

MGM was unable to recoup its $4,000,000 investment. As a result,

the studio imposed the block booking system on its other productions,

another precedent. While not a financial success, however, the film

still proved so popular that MGM was able to release it again in 1931,

adding music and sound effects for the sound era.

In 1959, a decade that saw the resurgence of epic productions,

MGM remade Ben-Hur for the wide screen, using state of the art

Panavision techniques and stereophonic sound. Directed by William

Wyler and starring Charlton Heston as Ben-Hur, this film again

features a spectacular, thundering chariot race that took four months

to rehearse and three months to produce. The sequence nearly

overshadowed the rest of the movie, leading some to dub Ben-Hur

‘‘Christ and a horse-race.’’ The film was a box office and critical

success, earning $40,000,000 in its first year and garnering 11

Academy Awards. Enjoying tremendous popularity and continuing

Ben-Hur’s tradition of establishing precedents, it was broadcast uncut

on network television in 1971, earning the highest ratings at that time

for any film. It has been rebroadcast and re-released in theaters

several times since then.

Few works can claim to have made the same impact as has

Wallace’s Ben-Hur. As a novel and a play, it offered many people

their first entry into the worlds of fiction and drama. In its various film

adaptations, it elevated Hollywood’s production values and defined

the genre of the religious epic. It also established many legal prece-

dents for stage and screen adaptations. The key to its enduring

popularity, however, is that it provided audiences around the world

with an exciting spectacle that combined piety and faith.

—Scott W. Hoffman

F

URTHER READING:

Babington, Bruce, and Peter William Evans. Biblical Epics: Sacred

Narrative in the Hollywood Cinema. Manchester, Manchester

University Press, 1993.

Forshey, Gerald E. American Religious and Biblical Spectaculars.

Westport, Connecticut, Praeger, 1992.

Searles, Baird. Epic! History on the Big Screen. New York, Harry N.

Abrams, 1990.

Towne, Jackson E. “Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur.” New Mexico Histori-

cal Review. Vol. 36, No. 1, December, 1961, 62-9.

Benneton

Italy-based clothier Benneton is best known for its ‘‘shock’’

advertising campaigns, many of which have sparked significant

controversy in many regions of the globe. In their 1990s campaign,

‘‘Sufferings of Our Earth,’’ the fashion designer’s ads showed among

other things a dying AIDS victim, a dead Bosnian soldier, an oil

smeared sea bird, and an overcrowded refugee ship. A series of ads in

1998 featured autistic and Down’s syndrome kids modeling their

clothing. The company operates some 7,000 stores in over 120

countries and had $2 billion in revenues in 1997. In addition to

apparel, Benneton also markets a wide range of products from racing

cars to sunglasses and condoms.

—Abhijit Roy

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Benneton Enters Condom Market.’’ Marketing. November 13, 1997.

Granatstein, Lisa. ‘‘Benetton’s Colors Dances with Mr.D.’’ Mediaweek.

February 23, 1998.

Rogers, Danny. ‘‘Benetton Plans to Show Down’s Syndrome Kids.’’

Marketing. August 13, 1998.

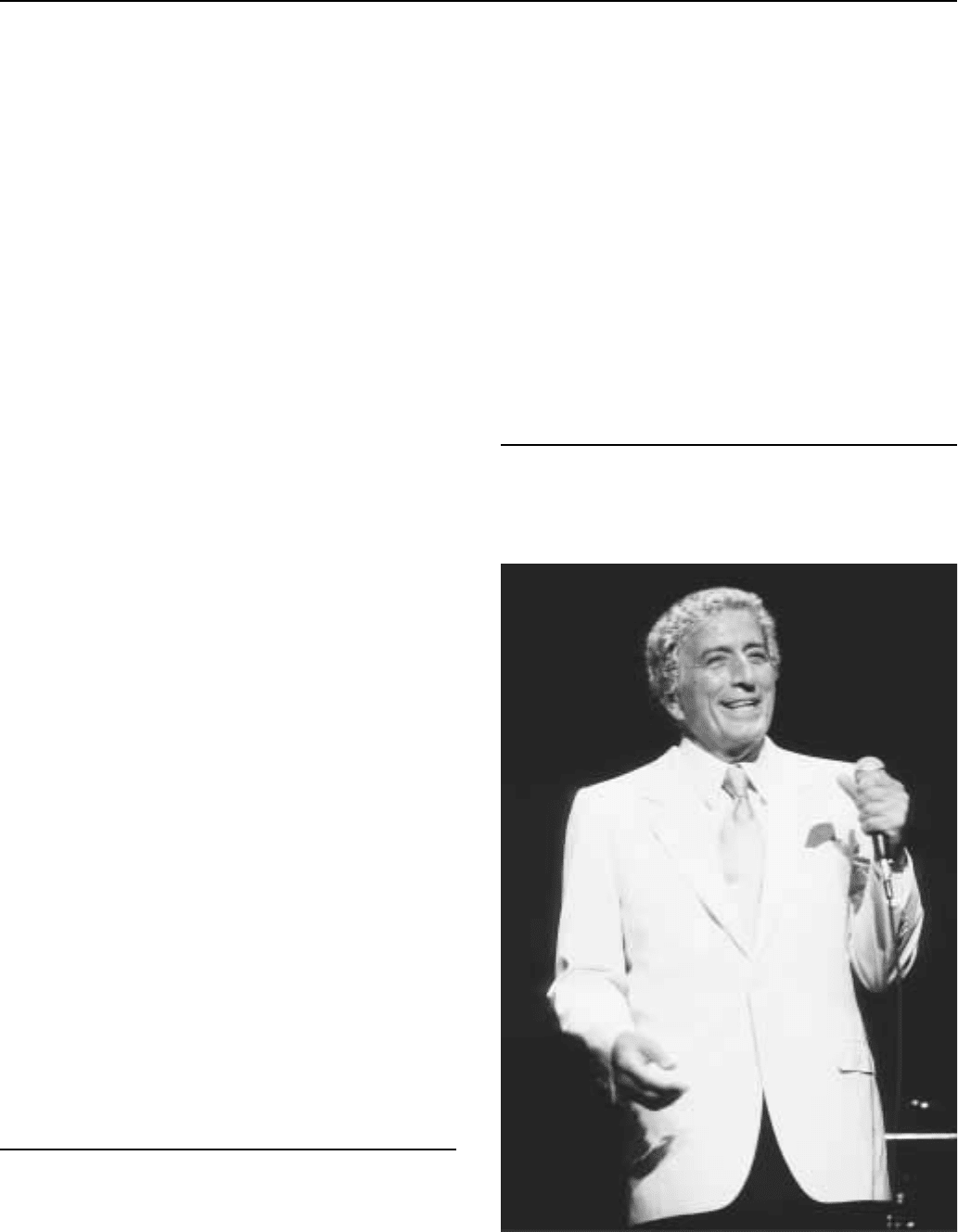

Bennett, Tony (1926—)

Through perseverance, professionalism, and impeccable musi-

cal taste, Tony Bennett has emerged in the era of MTV as the senior

statesman of the American popular song. Born Anthony Dominick

Tony Bennett

BENNY HILL SHOW ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

222

Benedetto in Queens, New York, Bennett joined the Italian-American

bel canto tradition represented by such singers as Frank Sinatra and

Vic Damone. In fact, Sinatra often publicly referred to Bennett as his

favorite singer, a validation that undoubtedly means as much as a

handful of gold records and Grammy awards combined.

Bennett’s musical career started slowly. After serving in the

armed forces in the final months of World War II, he studied vocal

technique under the GI Bill and supported himself with a variety of

jobs, including, according to some sources, a stint as a singing waiter.

His first break occurred when he came in second to Rosemary

Clooney on the network television show Arthur Godfrey’s Talent

Scouts in 1950. This exposure led to an introduction to Bob Hope,

who helped Bennett to land an engagement in one of New York’s

premier clubs. Later that year, Mitch Miller signed Bennett as a

recording artist for Columbia Records, and in 1951 he was named

male vocalist of the year by Cashbox magazine.

Always attracted to jazz as well as pop styling, Bennett teamed

up with some of the top musicians of the day, which gave him the

freedom to choose songs that were more to his taste than the hit-

oriented recording business normally allowed. Numerous records

during the mid and late 1950s show Bennett at his best, singing jazz-

inflected standards like ‘‘These Foolish Things’’ and ‘‘Blues in

the Night.’’

Nevertheless, Bennett experienced a long hitless period in the

early 1960s. It was during this time that the singer and his longtime

arranger and accompanist Ralph Sharon played a gig at the Fairmont

Hotel in San Francisco, where Bennett sang a new song by little-

known writers George Cory and Douglass Cross for the first time.

That song, ‘‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco,’’ changed the course of

Bennett’s career, earning him a sustained place on the charts in both

the United States and Great Britain. It also brought Bennett two

Grammy awards, for record of the year and best male vocal performance.

With his new public image, Bennett moved from supper clubs to

the concert stage, giving a landmark recorded performance at Carne-

gie Hall. In the mid-1960s, he had hits with such singles as ‘‘The

Good Life,’’ ‘‘A Taste of Honey,’’ and ‘‘Fly Me to the Moon.’’ Soon

after that, however, Bennett, like other interpreters of American pop

standards by Arlen, Gershwin, and Porter, began to suffer from the

record companies’ stubborn commitment to rock and roll. Bennett

was not interested in singing songs he did not love, although he did

compromise on a 1970 album titled Tony Bennett Sings the Great Hits

of Today, which included such songs as ‘‘MacArthur Park,’’ ‘‘Elea-

nor Rigby,’’ and ‘‘Little Green Apples.’’ More to his taste were two

albums made on the Improv label with the great jazz pianist Bill

Evans in 1975 and 1977. Bennett also appeared with Evans at the

Newport Jazz Festival and at Carnegie Hall.

In 1979, Bennett’s son Danny, a former rock guitarist, took over

his management, with a combination of shrewd marketing and

musical acuity that helped his father bridge the gap between the old

and new pop scene. It was this teaming that eventually led to the MTV

video and album Tony Bennett Unplugged in 1994. In an era when

smooth and mellow lounge music was reborn and martinis were once

again the official cocktail, the album was a huge hit. Always generous

to his younger colleagues—just as another generation of entertainers

had been generous to him—Bennett gave high praise to k.d. lang, who

joined him for a duet of ‘‘Moonglow,’’ and to Elvis Costello, who

harmonized on ‘‘They Can’t Take That Away from Me.’’

In addition to his singing career, Bennett is a serious painter in

oils, watercolors, and pastels. His work has been exhibited widely,

and he claims David Hockney as a major influence. A graduate of

New York’s High School of Industrial Art, Bennett often paints

familiar New York scenes, such as yellow cabs racing down a broad

avenue and Sunday bicyclers in Central Park, capturing the milieu in

which he lived, sang, and observed.

—Sue Russell

F

URTHER READING:

Bennett, Tony, with Will Friedwald. The Good Life. New York,

Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Hemming, Roy, and David Hajdu. Discovering Great Singers of

Classic Pop. New York, Newmarket Press, 1991.

The Benny Hill Show

English comic Benny Hill became an international celebrity with

his schoolboy brand of lecherous, burlesque humor. Bringing the

tradition of the British vaudeville to television in 1955, the pudgy Hill

hosted comedy series for the BBC and Thames Television over a

period of thirty-four years. Featuring slapstick and sight gags, The

Benny Hill Show always had a sexual energy, bursting with plenty of

double-entendres and leggy starlets. The show was edited for world-

wide syndication and became a cult phenomenon in the United States

beginning in 1979. American audiences quickly identified Red Skelton

as a main source of inspiration (Hill borrowed Skelton’s closing line,

‘‘Good night, God bless’’); but there was little sentimentality in the

ribaldry of Hill’s characters. Hill was always criticized for his sexist

obsessions, and his series in England was finally cancelled in 1989

because of complaints from the moral right and the politically correct

left. Hill died three years later, and, although English audiences voted

him ‘‘Funniest Man in the World’’ several times, he thought he never

received the critical recognition he deserved. But to many, Hill was a

genuine comic auteur, writing all his material and supervising every

randy shot for his show that was enjoyed in over one hundred countries.

—Ron Simon

F

URTHER READING:

Kingsley, Hilary, and Geoff Tibballs. Box of Delights. London,

MacMillan, 1989.

Robinson, J. ‘‘A Look at Benny Hill.’’ TV Guide. December 10,

1983, 34-36.

Smith, John. The Benny Hill Story. New York, St. Martin’s, 1989.

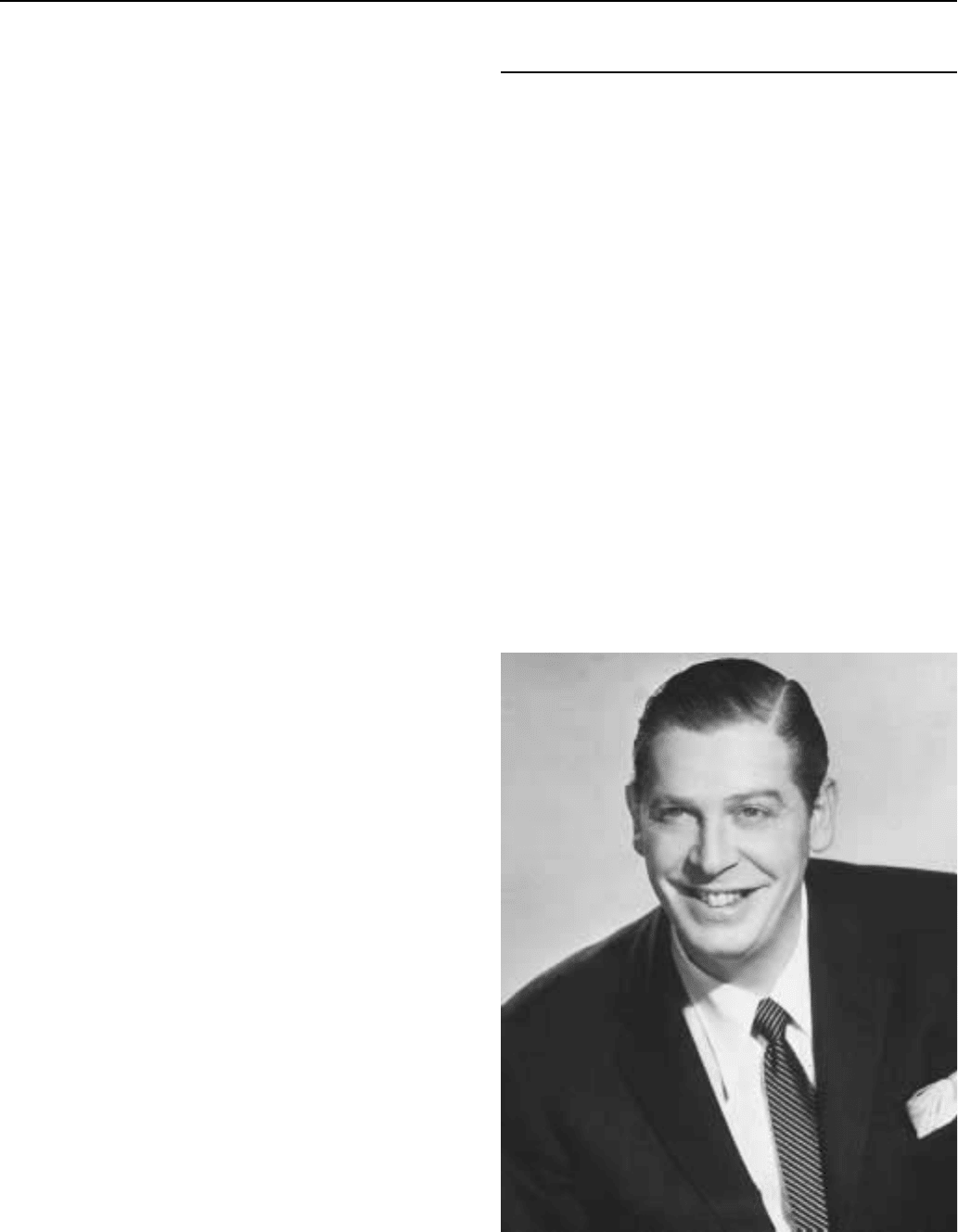

Benny, Jack (1894-1974)

Jack Benny is one of America’s most venerated entertainers of

the twentieth century. For over 50 years the nation identified with the

BENNYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

223

Jack Benny

persona that Benny created on the vaudeville circuit, sustained on

radio, and successfully transferred to television. Few performers have

lasted so long without any significant drop in popularity.

The character that Benny created exemplified the foibles of the

American Everyman. Benny realized early on that ‘‘if you want the

laughs you have to put something in a ridiculous light, even your-

self.’’ Benny was not a gifted clown or a sparkling wit, so he and his

writers crafted a well-rounded persona with the weaknesses and

imperfections of his audience. The Benny alter ego was penny-

pinching, vain, anxious, and never willing to admit his true age (he

was always 39 years old). Endless jokes were woven around these

shortcomings, with Benny always the object of ridicule. Although the

character had no identifiable ethnic or religious heritage, Americans

had a deep affection for this insecure, sometimes petulant, creation.

The comedian was born Benjamin Kubelsky in Waukegan,

Illinois on February 14, 1894, and began performing in vaudeville as a

violinist. Still a teenager, he discovered the public responded to his

jokes and wrong notes. Achieving moderate success on the New York

stage, Benny first appeared on radio in 1929 and began a NBC radio

series in 1932. Two years later, he was one of the medium’s most

popular entertainers. In 1935 he moved operations to Hollywood, and

Jell-O became a trusted sponsor.

Benny found his character worked better as part of a group and

helped to pioneer ‘‘gang’’ comedy. His wife, Sadie Marks, appeared

as a sometimes girl friend, Mary Livingstone, and assumed the

character’s name as her own. Eddie Anderson portrayed Benny’s

personal valet, Rochester, and was hailed as radio’s first black star.

Although there were stereotypical elements to Rochester’s characteri-

zation, a genuine bond grew between Benny and his employee that

transcended race. Don Wilson as the rotund announcer, Phil Harris as

the boozy bandleader, and Dennis Day as the boy singer rounded out

the stable of regulars ‘‘playing themselves.’’

Radio listeners delighted in Benny’s recurring gags and show

business feuds as well as such catchphrases as ‘‘Well!’’ and ‘‘Now

cut that out!’’ Mel Blanc was popular as the voice of Carmichael, the

bear that lived in the basement; the exasperated violin teacher,

Professor LeBlanc; and the bellowing railroad announcer (‘‘Anaheim,

Azusa, and Cucamonga!’’). Frank Nelson returned again and again as

the unctuous clerk who harassed customers by squawking ‘‘Yeeeesss!’’

Benny is best remembered for his ‘‘Your money or your life?’’

routine, in which a burglar demands a difficult answer from the stingy

comedian. After a long pause with the laughter building, Benny

delivered his classic line, ‘‘I’m thinking it over.’’ To Benny, timing

was everything.

The cast frequently spoofed western serials with the skit ‘‘Buck

Benny Rides Again.’’ The parody was made into a movie in 1940.

Benny made his first film appearance in the Hollywood Revue of

1929, but his radio stardom paved the way for substantial roles.

Among his notable movie vehicles, Benny appeared as a vain actor in

Ernst Lubitsch’s classic, To Be or Not to Be (1942); a confirmed city-

dweller in George Washington Slept Here (1942); and an avenging

angel in Raoul Walsh’s comedy, The Horn Blows at Midnight (1945).

In 1948 Benny took greater control of his career. He formed a

production company to produce his radio series and generate more

money for himself. William Paley also lured him to the CBS network.

Although his vaudeville compatriots, Ed Wynn and Milton Berle, had

become television stars in the late 1940s, Benny warmed slowly to the

possibilities of the visual medium. Beginning with his first special,

performed live in October 1950, Benny tried to approximate the radio

series as closely as possible, retaining his cast and adapting appropri-

ate scripts. Benny was also careful not to overexpose himself. Until

1953, The Jack Benny Show was a series of irregular specials on CBS;

then, for seven years, it ran every other week on Sunday nights, his

regular evening on radio. Beginning in 1960, the program aired every

week, switching to Tuesday and Friday during its five year run.

Benny brought to television a defined, identifiable character

forged during his stage and radio years. His persona was perfectly

suited for the requirements of the small screen. Benny underlined his

characterization with subtle gestures and facial expressions. The

stare, which signaled Benny’s pained exasperation, became his visual

signature. Like the pause in radio, Benny’s stare allowed the audience

to participate in the joke.

The Benny program combined elements of the variety show and

the situation comedy. As host, Benny, always in character, opened the

proceedings with a monologue before the curtain. The bulk of each

program was Benny performing with his regulars in a sketch that

further played off his all-too-human frailties. Guest stars were also

invited to play themselves in Benny’s fictional world. Since the

format was a known quantity, many movie stars made their television

comedy debut on the Benny program, including Barbara Stanwyck,

Marilyn Monroe, Gary Cooper, and James Stewart.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Benny’s writers kept his

persona fresh and vital to a new generation of viewers. They crafted

sketches around such television personalities as Dick Clark, Ernie

BERGEN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

224

Kovacs, and Jack Webb. Benny also stayed eternally young by

donning a wig and playing guitar on occasion. When his weekly series

ended in 1965, he returned to comedy specials. Whether playing

violin with Isaac Stern or impersonating a surfer in a routine with the

Beach Boys, Jack Benny was able to bridge audiences of different

ages and tastes.

Jack Benny was a comedian’s comedian. His sense of under-

stated style and exquisite delivery shaped a generation of entertainers

from Johnny Carson to Kelsey Grammer. He was also a national

institution. Although the public knew in reality that he was a kind and

generous person, they wanted to believe the worst. Jack Benny held

up a mirror to America’s failings and pretensions. As his friend Bob

Hope said in farewell after his death in 1974, ‘‘For Jack was more

than an escape from life. He was life—a life that enriched his

profession, his friends, his millions of fans, his family, his country.’’

—Ron Simon

F

URTHER READING:

Benny, Jack and Joan. Sunday Nights at Seven: The Jack Benny Story.

New York, Warner, 1990.

Fein, Irving. Jack Benny: An Intimate Biography. New York,

Putnam, 1976.

Josefberg, Milt. The Jack Benny Show. New Rochelle, New York,

Arlington House, 1977.

The Museum of Television & Radio. Jack Benny: The Radio and

Television Work (published in conjunction with an exhibition of

the same title). New York, Harper, 1971.

Bergen, Candice (1946—)

Candice Bergen may be the only female television star to be

known and loved as a curmudgeon. Most noted curmudgeons are

male, like Lou Grant of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Archie Bunker

of All in the Family, Homer Simpson from The Simpsons, and Oscar

the Grouch from Sesame Street. Bergen’s alter-ego, Murphy Brown,

on the other hand, is the queen of curmudgeons. Despite her manly

traits, Murphy has gone down in history as the only television

curmudgeon to be criticized by the vice president of the United States

and to be used as an argument in a national debate on family values.

Her willingness to challenge traditional female roles and issues

revolving around what is perceived as ‘‘decency,’’ have, willingly or

not, made her one of the twentieth century’s most political actresses.

Murphy Brown, created by Diane English, was a female reporter

who learned to operate in a man’s world. She adopted what are

generally considered male characteristics: intelligence, aggressive-

ness, ambitiousness, and perseverance. It has been suggested that

reporter Linda Ellerbee was the specific role model for Bergen’s

character, but only Bergen herself could have made Murphy Brown

so lovable through a decade of the weekly series of the same name,

covering almost every political topic with satiric wit.

Candice Bergen grew up in an elite section of Beverly Hills

playing with the children of Walt Disney, Judy Garland, Gloria

Candice Bergen

Swanson, Jimmy Stewart, and other Hollywood notables. Her beauty

was inherited from her mother, Frances Western, a former model who

received national attention as the Ipana girl from a toothpaste adver-

tisement. Her talent came from her father, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. In

her autobiography, Knock Wood, Bergen tells of being jealous of her

father’s famous sidekick, marionette Charlie McCarthy, and of spending

years of her life trying to make her father proud.

Noted for her outstanding beauty, Candice Bergen was not

always taken seriously as an individual. Nonetheless, by the time she

accepted the role of Murphy Brown Bergen was well respected as an

international photojournalist and as a writer. She had also starred in a

number of high-profile films, most notably, Mary McCarthy’s The

Group, in which she played the distant and lovely lesbian Lakey.

Bergen also received critical acclaim as the ex-wife of Burt Reynolds

in the romantic comedy Starting Over.

At the age of 33 Bergen met the famed French director Louis

Malle. Friends say they were destined to meet and to fall in love. The

pair maintained a bi-continental marriage until his death in 1995,

leaving Bergen to raise their daughter Chloe. After Malle’s death,

Bergen devoted her time exclusively to Chloe and to her television

show. By all accounts, the cast of Murphy Brown was close and

Bergen said in interviews that Faith Ford (who played Corky Sher-

wood) had been particularly comforting during her mourning over the

BERGMANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

225

death of her husband. This personal closeness gave the cast a

professional camaraderie that was evident to audiences.

In 1988, Murphy Brown introduced the cast of F.Y.I, a fictional

news show. Murphy Brown (Candice Bergen), Frank Fontana (Joe

Regalbuto), Jim Dial (Charles Kimbrough), and Corky Sherwood

(Faith Ford) shared anchor duties on air and traded wisecracks and

friendship off the air. They were joined by producer Miles Silverberg

(Grant Shaud), artist and handyman Eldin (Robert Pastorelli), and

barkeeper Phil (Pat Corley). In 1996, Lily Tomlin replaced Shaud as

the producer. Plot lines ranged from grocery shopping and conscious-

ness raising, to romance, divorce, and the White House cat, Socks.

The two most notable story lines involved unwed motherhood and

breast cancer. During its tenure, Murphy Brown won 18 Emmys, five

of them for its star. Bergen then withdrew her name from competition.

In 1992, Murphy Brown, a fictional character on a television

show, became pregnant. After much soul searching, she decided to

raise her baby without a father. In May of that election year, Vice

President Dan Quayle stated in a speech (allegedly against the advise

of his handlers): ‘‘It doesn’t help matters when prime time television

has Murphy Brown—a character who supposedly epitomizes today’s

intelligent, highly paid professional woman—mocking the impor-

tance of fathers by bearing a child alone and calling it just another

’lifestyle choice.’’’ The media was delighted, and the debate was on.

In the fall of 1992, Bergen and Diane English (who had offered

to debate Quayle on the issue) had their say when Murphy responded

to the vice president on F.Y.I. by gently reminding him that families

come in all shapes and sizes. She then chided Quayle by agreeing that

there were serious problems in American society and suggested that

the vice president could blame the media, Congress, or an administra-

tion that had been in power for 12 years . . . or, he could blame her.

The episode ended with the dumping of 1,000 pounds of potatoes in

Quayle’s driveway, a reference to an occasion when Quayle mis-

spelled the word as a judge in an elementary speech contest. The

episode won the Emmy for Best Comedy of 1992.

The final season of Murphy Brown (1997-1998) ended on a more

solemn note. Murphy discovered that she had breast cancer. Through-

out the season, real cancer survivors and medical advisors helped to

deliver the message that cancer was serious business and that there

was hope for recovery. An episode devoted to the medicinal use of

marijuana demonstrated the strong bond among the cast and proved

that the show could still arouse controversy. The final episode of the

season was filled with emotional farewells and celebrated guest stars,

including Bette Midler as the last in a long line of Murphy’s

secretaries, Julia Roberts, and George Clooney. God, in the person of

Alan King, also made an appearance, as did Robert Pastorelli (Eldin)

and Pat Corley (Phil), both of whom had left the series years before to

pursue other interests.

Various media reports have indicated that Candice Bergen may

become a commentator for 60 Minutes. With her experience as a

photojournalist and with her ten years on F.Y.I., Bergen is imminently

qualified to engage in a serious debate of national issues.

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Bergen, Candice. Knock Wood. Boston, G. K. Hall & Compa-

ny, 1984.

Morrow, Lance. ‘‘But Seriously Folks.’’ Time. June 1, 1992, 10-12.

Bergen, Edgar (1903-1978)

Chicago-born Edgar Bergen put himself through college as a

part-time ventriloquist with a doll he had acquired while in high

school. It was to his relationship with this doll, the cheeky, monocled

toff Charlie McCarthy, that Edgar Bergen owed his fame and a special

Oscar. Edgar and Charlie played the vaudeville circuit, then became

popular radio performers in the medium’s hey-day. They made

several appearances in movies, beginning with The Goldwyn Follies

(1938) and including Charlie McCarthy Detective (1939), while

television further increased their visibility. They periodically had

other puppets in tow, most famously Mortimer (‘‘How did you get to

be so dumb?’’) Snerd. The father of actress Candice Bergen, Edgar,

sans Charlie, played a few minor roles in films, but it is for his

influence on the art of puppetry that he is remembered. Muppet

creator Jim Henson acknowledged his debt to Bergen’s skills, and it

was in The Muppet Movie (1979) that he made his last appearance.

Bergen bequeathed Charlie McCarthy to the Smithsonian Institute.

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Katz, Ephraim. The International Film Encyclopedia. New York,

HarperCollins, 1994.

Press, Skip. Candice & Edgar Bergen. Persippany, New Jersey,

Crestwood House, 1995.

Bergman, Ingmar (1918—)

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s name is virtually synony-

mous with the sort of intellectual European films that most critics love

to praise—but that many moviegoers love to hate. His complex

explorations of sweeping topics like loneliness, spiritual faith, love,

and death have been closely imitated, but also parodied for their overt

reliance on symbol and metaphor, for their philosophical dialogue,

and for their arguably opaque dreamlike qualities. Famous Bergman

images reappear throughout the spectrum of popular culture, images

like that of Death, scythe in hand, leading a line of dancing victims

through an open field, the figures silhouetted against the sky. Bergman

began his prolific career in Stockholm during the 1930s. He directed

theater and eventually radio and television dramas. His catalogue of

over fifty films includes classics like The Seventh Seal (1956), Wild

Strawberries (1957), Through a Glass Darkly (1960), and Fanny and

Alexander (1983).

—John Tomasic

F

URTHER READING:

Bergman, Ingmar. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. New

York, Viking, 1988.

BERGMAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

226

Cohen, Hubert. Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession. New York,

Twayne, 1993.

Steene, Birgitta. Ingmar Bergman: A Guide to References and

Resources. Boston, G.K. Hall, 1987.

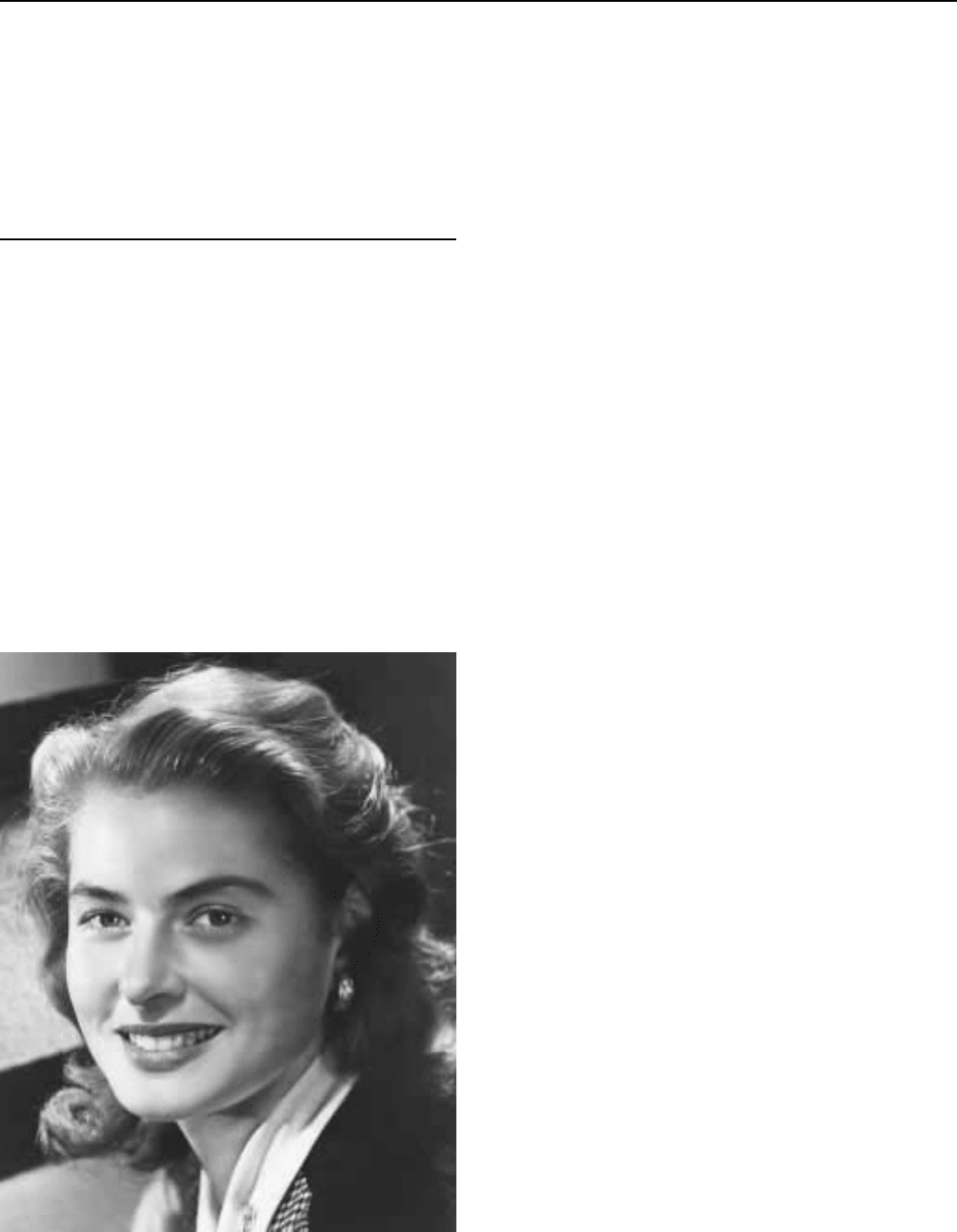

Bergman, Ingrid (1915-1982)

A star in Swedish, French, German, Italian, and British films

before emigrating to the United States to star in Intermezzo in 1939,

Ingrid Bergman, with her Nordic freshness and vitality, coupled with

her beauty and intelligence, quickly became the ideal of American

womanhood and one of Hollywood’s most popular stars. A love affair

with Italian director Roberto Rossellini during the filming of Stromboli

in 1950 created a scandal that forced her to return to Europe, but she

made a successful Hollywood comeback in 1956, winning her second

Academy Award for the title role in Anastasia.

Born in Stockholm to a tragedy-prone family, she suffered at age

two the death of her mother. Her father died when she was twelve, a

few months before the spinster aunt who had raised her also died. She

was sent to live with her uncle and later used her inheritance to study

acting at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. With the encour-

agement of her friend Dr. Peter Lindstrom, who became her first

husband in 1937, she turned to the cinema, playing a hotel maid in her

Ingrid Bergman

debut film Monkbrogreven (1934). The turning point in her career

came in 1937, when the Swedish director Gustaf Molander chose her

as the lead in the romantic drama Intermezzo, about a famous violinist

who has an adulterous affair with a young pianist.

When David Selznick saw a print of Bergman in the Swedish

film, he was unimpressed, but he was persuaded by Katharine Brown,

his story-buyer, that the proposed American remake of Intermezzo

would only be successful with Ingrid in the role of the pianist. He

signed her to a contract for the one film, with an option for seven

years. When Intermezzo, A Love Story, also starring Leslie Howard,

was released in 1939, Hollywood saw an actress who was completely

natural in style as well as lack of makeup. Film critic James Agee

wrote that ‘‘Miss Bergman not only bears a startling resemblance to

an imaginable human being; she really knows how to act, in a blend of

poetic grace with quiet realism.’’ Selznick exercised his option for the

extended contract and recalled her from Sweden.

While waiting for Selznick to develop roles for her, Bergman

played on Broadway in Liliom and was loaned out to MGM for two

dramatic roles, as the governess in love with Warner Baxter in Adam

Had Four Sons (1941) and as Robert Montgomery’s ill-fated wife in

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941). MGM offered her the role of the

ingenue in the latter film, but Bergman, always willing to take

chances, begged for the role of the floozy and exchanged parts with

Lana Turner. Theodore Strauss, writing in the New York Times,

praised Bergman’s ‘‘shining talent’’ in making something of a small

part. He added that Turner and the rest of the cast moved ‘‘like well-

behaved puppets.’’

In 1942 Warner Brothers, desperate for a continental heroine

after being turned down by Hedy Lamarr, borrowed Bergman from

Selznick to play opposite Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca (1942).

The role made Bergman a surefire box-office star and led to her

appearing opposite Gary Cooper the following year in Hemingway’s

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). Selznick’s Swedish import was now

in demand for major roles by several studios, and in 1944 MGM

signed her for her Academy Award winning role as the manipulated

wife in Gaslight. Her talent and popularity attracted Alfred Hitch-

cock, who gave her leads in two of his finest suspense thrillers,

Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946). Then occurred a succession

of ill-chosen parts, along with a shocking scandal, and the film

Notorious became her last successful film for a decade.

Her affair with Roberto Rossellini, which erupted during the

shooting of Stromboli on location in Italy in 1950, resulted in the birth

of a daughter and a barrage of international criticism. Although she

married Rossellini as soon as possible after her divorce, her fans, and

particularly those in America, were unwilling to forgive her. Stromboli

was boycotted by most of the movie-going public. Rossellini directed

her in Europa ‘51 in 1952, with the same dismal response.

In 1957 the Fox studios offered her $200,000 for the title role in

Anastasia. She agreed to the terms, the film was shot in Britain, and it

became a world-wide hit, earning Ingrid her second Oscar as well as

the forgiveness of her fans. In 1958 two more films shot in Britain

were released with great success: Indiscreet, with Cary Grant, and

The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, based on the true story of a missionary

in China. She continued to make films in Europe, but most of them

received no bookings in the United States. Columbia lured her back to

Hollywood for a two-picture deal, however, and she made the popular

Cactus Flower (1969), co-starring Walter Matthau, and A Walk in the

BERKELEYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

227

Spring Rain (1970) with Anthony Quinn. Her last role was that of

Golda Meir, the Israeli prime minister, in a drama made for television,

A Woman Called Golda (1981). She made her home in France for the

last 32 years of her life and died in London on August 29, 1982.

—Benjamin Griffith

F

URTHER READING:

Bergman, Ingrid, and Alan Burgess. Ingrid Bergman: My Story. New

York, Delacorte, 1980.

Leamer, Laurence. As Time Goes By: The Life of Ingrid Bergman.

New York, Harper & Row, 1986.

Quirk, Lawrence J. The Complete Films of Ingrid Bergman. New

York, Carol Communications, 1989.

Spoto, Donald. Notorious: The Life of Ingrid Bergman. New York,

HarperCollins, 1997.

Taylor, John Russell. Ingrid Bergman. New York, St. Martin’s

Press, 1983.

Berkeley, Busby (1895-1976)

The premier dance director of 1930s Hollywood musicals,

Busby Berkeley created outrageously fantastical production numbers

Busby Berkeley with actress Connie Russell.

featuring synchronized hordes of beautiful women moving in kalei-

doscopic patterns that took audiences on surreal journeys away from

the blues of their Depression-era realities. Berkeley took the spectacle

traditions of popular American stage entertainments and the pulchri-

tudinous aesthetic of the Ziegfeld Follies and extended them through

cinematic techniques. His groundbreaking dance sequences revolu-

tionized the way musicals were filmed by demonstrating how the

camera could be used to liberate the directorial imagination from the

constraints of theatrical realism. The distinctive look of his dancing

screen geometries influenced the visual aesthetic of films, animation,

television commercials, and music videos throughout the twentieth

century. The term ‘‘busby berkeley’’ appears in the American The-

saurus of Slang, defined as ‘‘any elaborate dance number.’’

Born William Berkeley Enos on November 29, 1895, to a

theatrical family in Los Angeles, Berkeley began choreographing

while serving in the army. Stationed in France in 1917, Berkeley

designed complex parade drills for his battalion, honing his abilities

to move multitudes of bodies rhythmically through cunning configu-

rations. After the war, Berkeley worked as an actor and, by 1921, had

begun directing plays and musicals. Though he had no dance training,

Berkeley soon became known for staging innovative, well-ordered

movement sequences for Broadway revues and musicals, including

the 1927 hit A Connecticut Yankee.

In 1930, Samuel Goldwyn brought Berkeley to Hollywood.

Before embarking on his first assignment, directing the dance num-

bers for the film musical Whoopee!, Berkeley visited neighboring sets

to learn how the camera was used. The pre-Berkeley approach to

filming musicals was akin to documenting a theatrical production.

Four stationary cameras were positioned to capture the performance

from a variety of angles. The various shots were creatively combined

during the editing process. Berkeley chose, instead, to use only one

camera, which he moved around the set, thereby allowing his filming,

rather than the editing, to dictate the flow of his numbers. Though a

few attempts had been made earlier to film dance sequences from

points of view other than that of a proscenium stage, it was Berkeley

who fully and most inventively exploited the variety of possible

camera placements and movements. Berkeley’s work is characterized

by plenty of panning and high overhead shots that sometimes necessi-

tated cutting a hole in the studio ceiling and eventually resulted in his

building a monorail for his camera’s travels.

In 1932 Berkeley began a seven-year affiliation with Warner

Bros. where he created the bulk of his most remarkable dance

sequences for films such as Gold Diggers of 1933 and Dames (1934).

His first film there, 42nd Street (1933), rescued the studio from

bankruptcy and rejuvenated the film musical at a time when the

genre’s popularity had waned.

Berkeley’s numbers had little to do with the text or story line of

the films. His dances were often voyeuristic and contained undeniable

sexual symbolism. Censors were hard-pressed to challenge their

naughtiness, however, because the eroticism was in abstract forms—

shapes that resembled giant zippers unzipping, long straight bodies

diving into circles of women swimming below, or a row of huge rising

bananas. No individual dancer ever did anything that could be

interpreted as a sexual act.

In Berkeley’s dance numbers there is very little actual dancing. It

is the camera that executes the most interesting choreography. Berke-

ley was unconcerned with dance as physical expression and preferred

BERLE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

228

to focus his creative efforts on cinematic tricks. The simple moves

and tap dancing in Berkeley’s routines were taught to the dancers by

his assistants. Berkeley was not interested in the talents of so-

lo dancers, but in how he could use numerous bodies to form

magnificent designs.

In 1939, when Warner Bros. lost interest in producing big

musicals, Berkeley went to MGM where he continued to create his

signature-style dance sequences for films such as Lady Be Good

(1941). He was also given the opportunity to both choreograph and

direct three Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland vehicles, Babes in Arms

(1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), and Babes on Broadway (1941).

By the mid-1940s, Berkeley-esque movie musicals—those with

flimsy plots interrupted by abstract movement sequences—were on

their way out in favor of musicals in which the songs and dances were

integrated with the drama. The demand for Berkeley’s work gradually

diminished. He retired in 1954 but returned to create numbers for the

1962 circus extravaganza, Jumbo.

By 1970, though the public had long tired of gigantic film

musicals, there developed a resurgence of interest in Berkeley’s work,

seen as camp yet appreciated within the period’s wave of 1930s

nostalgia. Berkeley was interviewed extensively during this period,

while his films were shown on late-night television and in numerous

retrospectives. The 1971 revival of No, No, Nanette reintroduced

Broadway audiences to old-style, large-scale, tap-dance routines

reminiscent of Berkeley’s heyday. Though he made no artistic

contribution to this production, he was hired as an advisor, as it was

thought Berkeley’s name would boost ticket sales.

While Berkeley’s work was light entertainment, his personality

had a dark side, evidence of which can be found in aspects of his films

as well as in his unsuccessful suicide attempts, his inability to

maintain relationships (having been married six times), and his

excessive drinking: in 1935 Berkeley was tried for the murders of

three victims of his intoxicated driving. Some of Berkeley’s dances

indicate an obsession with the death of young women, including his

favorite sequence—‘‘Lullaby of Broadway’’ from Gold Diggers of

1935—which ends with a woman jumping to her death from atop

a skyscraper.

On March 14, 1976, Berkeley died at his home in California.

Though his oeuvre is an indelible part of the popular entertainment

culture of the 1930s—as he so brilliantly satisfied Americans’ escap-

ist needs during one of the country’s bleakest eras—his bewitching,

dream-like realms peopled by abstract forms made of objectified

women intrigue and influence each generation of spectators and

visual artists that revisits his films.

—Lisa Jo Sagolla

F

URTHER READING:

Delamater, Jerome. Dance in the Hollywood Musical. Ann Arbor,

Michigan, UMI Research Press, 1981.

Pike, Bob, and Dave Martin. The Genius of Busby Berkeley. Reseda,

California, Creative Film Society, 1973.

Rubin, Martin. Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of

Spectacle. New York, Columbia University Press, 1993.

Thomas, Tony, and Jim Terry with Busby Berkeley. The Busby

Berkeley Book. Greenwich, Connecticut, New York Graphic

Society, 1973.

Berle, Milton (1908—)

Milton Berle, a former vaudevillian, film actor, and radio

comedian, was television’s first real star. Credited with selling over a

million television sets during his first years hosting the weekly

Tuesday night NBC program Texaco Star Theatre, Berle became post

war America’s beloved ‘‘Uncle Miltie.’’ Since Texaco Star Theatre

first aired in 1948, only a year after the three major networks first

began broadcasting programming on the new medium, much of

Berle’s urban audience was watching television in communal envi-

rons—in neighbors’ homes, in taverns, and in community centers. A

1949 editorial in Variety magazine heralded the performer for his

impact on the lives of city viewers: ‘‘When, single handedly, you can

drive the taxis off the streets of New York between 8 and 9 on a

Tuesday night; reconstruct neighborhood patterns so that stores shut

down Tuesday nights instead of Wednesdays, and inject a showman-

ship in programming so that video could compete favorably with the

more established show biz media—then you rate the accolade of

‘Mr. Television.’’’

Yet, the brash, aggressive, ethnic, and urban vaudeville style that

made him such a incredible phenomenon during television’s early

years were, ironically, the very traits that lead to his professional

decline in the mid-1950s. As television disseminated into suburban

and rural areas, forever altering audience demographics, viewers

turned away from Berle’s broad and bawdy antics and towards the

middle-class sensibilities of domestic sitcoms such as I Love Lucy and

Milton Berle