Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BERLEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

229

The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Nevertheless, his infusion of

vaudeville-style humor would impact the form and functions of

television comedy for decades.

Born in Harlem in 1908, Berle (whose birth name was Mendel

Berlinger) was the second youngest of Moses and Sarah (later

changed to Sandra) Berlinger’s five children. His father, a shopkeep-

er, was often sick and unable to work. His mother tried to bring in

money working as a store detective, but it was a very young Milton

who became the real breadwinner of the family. After winning a

Charlie Chaplin imitation contest at the age of five, Sarah became

convinced that her son had an innate comedic talent. As his manager,

she got him work in Biograph-produced silent films, performing

alongside the likes of Pearl White (in the famous Perils of Pauline

serial), Mary Pickford, and Charlie Chaplin. He then performed in a

number of traveling vaudeville ‘‘kid acts’’ and made his first appear-

ance on Broadway in a 1920 production of Floradora. For four years

Berle was teamed with Elizabeth Kennedy in a highly successful boy-

girl comedy act on the Keith-Albee circuit. But, after Kennedy left to

their act to get married, Berle, who was sixteen, found he had grown

too tall to continue performing in kid acts. It was at this point that he

developed his city-slicker, wise-cracking, physically frenetic, adult

stage personality. His new act included a bit of soft-shoe, some

pratfalls, one-liners, impersonations of comedians such as Eddie

Cantor, and, occasionally, a drag performance. By the late 1920s, he

had become a vaudeville headliner and master of ceremonies, often

breaking attendance records at venues such as the famous Palace

Theatre in Manhattan.

As Berle garnered praise for his comic timing and style many of

his fellow comedians complained loudly and bitterly about his

penchant for ‘‘stealing’’ material. Berle countered such accusations

with his firm belief that jokes were public property and by incorporat-

ing his reputation as the ‘‘Thief of Bad Gags’’ into his on-stage

persona. But ironically, just as the comedian’s star was rising in the

early 1930s, vaudeville entered a slump from which it would never

recover. While performing in nightclubs and in Broadway shows,

Berle tried his hand in radio. Yet, unlike other former vaudevillians

such as Jack Benny and Eddie Cantor who found national stardom on

the medium, Berle was never a success on radio—even though he

starred in over six different programs. This was due, in large part, to

Berle’s reliance on physical humor and visual cues instead of scripted

jokes and funny scenarios.

After failing in radio, Berle attempted to parlay his visual talents

into a movie career. Beginning with RKO’s New Faces of 1937, the

comedian completed nine features in six years. Yet, most of them

were ‘‘B’’ pictures and none of them attracted significant numbers at

the box office. Although film allowed Berle to employ the essential

physical cues of his humor, the medium proved too constricting for

him as there was no audience interaction nor was there any room for

ad-libbing or spontaneous pratfalls, elements essential to his perform-

ance style. Instead of seeing the ways in which his comedy was

simply unsuited to the aesthetic characteristics of radio and film, the

comedian (as well as many radio and Hollywood executives) began to

question his appeal to a mass audience. So, Berle returned to what he

knew best—working in front of a live audience in nightclubs and

legitimate theaters.

In the spring of 1948, Berle was approached by Kudner, Texaco’s

advertising agency, to appear as a rotating host on their new television

program. Although the agency had tried out other top comedy names

such as Henny Youngman, Morey Amsterdam, and Jack Carter

during their trial spring and summer, it was Berle that was chosen as

the permanent host of the program for the following fall. It was the

comedian, not the producers, who crafted the format and content on

the show, as, at least for the first year on air, Berle was the program’s

sole writer and controlled every aspect of the production including

lighting and choreography. His program and persona were an imme-

diate hit with a primarily urban audience accustomed to the limited

offerings of wrestling, roller derbys, news, and quiz programs. The

vaudeville-inspired format of Texaco Star Theatre, although popular

on radio, had not yet made it onto television, and Berle’s innovative

and flamboyant style proved irresistible. His aggressive emphasis on

the physical aspects of comedy, slick vaudeville routines, ability to

ad-lib, expressive gestures, and quick tongue made him an enormous

success in an industry looking to highlight visuality and immediacy.

What came to be known as the ‘‘Berle craze’’ not only brought major

profits to NBC and Texaco, it also set off a proliferation of simi-

lar variety shows on television. Berle was rewarded for this with

an unprecedented 30 year contract with NBC guaranteeing him

$200,000 a year.

Berle became infamous with post war audiences for his drag

routines, impersonations, and his constant joking references to his

mother. Berle’s relationship with Sarah was a key element in his on-

and off-stage persona. Almost every article written about Berle

during his years on television included at least one reference to the

loving, but perhaps over-bearing, stage mother. Although reinforcing

a long-standing cultural stereotype of the relationship between Jewish

mothers and their sons, Berle’s constant references to his mother

helped domesticate his image. Often criticized for his inclusion of

sexual innuendoes, ethnic jokes, and other material best suited to an

adult nightclub audience, Berle, his sponsor, and NBC needed to

ensure Texaco’s appeal to a family audience. Although Sarah Berle

helped remind the public of Berle’s familial origins, his own troubled

relationship with his first wife dancer Joyce Matthews threatened to

taint his image as a wholesome family man. After adopting a child

with Berle and then divorcing him twice, Matthews attempted suicide

in the home of theatrical producer Billy Rose, her married lover. This

scandal, along with rumors of Berle’s own extramarital affairs, left

him with a questionable reputation in an age when morality and duty

to one’s family was considered a man’s utmost responsibility.

Just as his personal life was under scrutiny, so was his profes-

sional life. His popularity with audiences was beginning to wane in

the early 1950s and a new style of comedy was on the horizon

threatening to usurp his standing as television’s most prominent face.

In the fall of 1952, after the program’s ratings began to drop and Berle

was hospitalized for exhaustion, the producers of Texaco tried to

revamp the program’s format by placing Berle within a situational

context and introducing a regular cast of characters. This move,

however, did not save the show and Texaco dropped their sponsorship

at the end of that season. Berle acquired a new sponsor and continued

his program as The Buick-Berle Show for two more seasons until it to

was taken off the air.

Although starring in The Milton Berle Show for one season in

1955 and appearing on various television programs and specials in the

late 1950s and early 1960s, Berle never regained his once impenetra-

ble hold on the American television audience. Eventually renegotiating

his contract with NBC in 1965 to allow him to perform on other

networks, Berle made quite a few guest appearances on both comedy

and dramatic programs. In addition, he appeared in a number of films

BERLIN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

230

including The Muppet Movie in 1979 and Woody Allen’s Broadway

Danny Rose in 1984. Since then, he has been honored with numerous

professional awards and in the late 1990s published his own magazine

Milton with his third wife Lorna. Exploiting the nostalgia for the

accouterments of a 1950s lifestyle, the magazine tried, with limited

success, to revive Berle’s persona for a new generation with the motto

‘‘we drink, we smoke, we gamble.’’

—Sue Murray

F

URTHER READING:

Adair, Karen. The Great Clowns of American Television. New York,

McFarland, 1988.

Berle, Milton. B.S. I Love You. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1987.

Berle, Milton with Haskel Frankel. Milton Berle: An Autobiography.

New York, Delacourte, 1974.

‘‘Highlights 48-49 Showmanagement Review: Television Awards.’’

Variety, July 27, 1949, 35.

Rader, Dorothy. ‘‘The Hard Life, the Strong Loves of a Very Funny

Man.’’ Parade magazine, The Boston Globe. March 19, 1989, 6.

Wertheim, Frank. ‘‘The Rise and Fall of Milton Berle.’’ American

History/American Television. John O’Connor, editor. New York,

Fredrick Ungar Publications, 1983, 55-77.

Berlin, Irving (1888-1989)

Irving Berlin’s popular music served as a social barometer for

much of the twentieth century: it marched to war with soldiers,

offered hope and inspiration to a nation in bleak times, and rejoiced in

the good things embodied in the American way of life. It also

provided anthems for American culture in such standards as ‘‘White

Christmas,’’ ‘‘Easter Parade,’’ ‘‘God Bless America,’’ and ‘‘There’s

No Business Like Show Business.’’

Born Israel Baline on May 11, 1888, in Temun, Siberia, Berlin

fled with his family to America to escape the Russian persecution of

Jews. They arrived in New York in 1893, settling in Manhattan’s

Lower East Side. Compelled by poverty to work rather than attending

school, Berlin made money by singing on streetcorners and later

secured a job as a singing waiter at the Pelham Cafe. During this time,

he also began writing songs of his own, and in 1907 he published

‘‘Marie from Sunny Italy,’’ signing the work I. Berlin and thereby

establishing the pseudonym under which he would become so

well known.

Berlin continued his involvement in the burgeoning music

industry as a young man, initially working at odd jobs in the

neighborhood that was becoming known as Tin Pan Alley and

eventually securing a job as a lyricist for the music-publishing firm of

Waterson & Snyder. In 1911, his ‘‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’’

became a huge hit and immediately earned him the title ‘‘King of Tin

Pan Alley.’’ Entirely self-taught as a musician, Berlin developed a

unique musical style by playing only on the black keys. Most of his

early songs were therefore written in the key of F-sharp, but, by using

a transposing keyboard, Berlin was able to compose in various keys.

By the 1920s, Berlin had become one of the most successful

songwriters in the country, despite his lack of formal training.

Opening the Music Box Theater with Joseph N. Schenck and Sam

Harris in 1921, Berlin began to stage his own revues and musical

comedies. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, Berlin, like many

others, lost his fortune. His misfortunes did not last long, and he

returned to the theater with the show, Face the Music (1932). Berlin

received his greatest accolades for the Broadway musical, Annie Get

Your Gun (1946), starring Ethel Merman, which introduced the

undeclared anthem of show business, ‘‘There’s No Business Like

Show Business.’’

Established on the Broadway stage, Berlin’s took his musical

talents to Hollywood, writing the scores for such hit musical films as

Top Hat (1935) and Holiday Inn (1942). One song from Holiday Inn,

‘‘White Christmas,’’ remains even today the best-selling song ever

recorded. Written during World War II, the song’s great appeal lay in

part in its evocation of an earlier, happier time, enhanced greatly by

Bing Crosby’s mellow, wistful delivery.

Berlin’s songs have also served as a rallying cry for the nation

during two world wars. While serving in the army in World War I,

Berlin wrote patriotic songs for the show Yip, Yip Yaphank (1918),

and in 1942 he wrote This Is the Army. The proceeds from perform-

ances of the latter totalled over ten million dollars, and were donated

to the Army Relief Fund. Berlin’s most famous patriotic work

remains the song, ‘‘God Bless America,’’ written initially during

World War I but sung in public for the first time by Kate Smith for an

Armistice Day celebration in 1938.

Berlin also wrote some of the most popular love ballads of the

century. ‘‘When I Lost You’’ was written in honor of his first wife,

who died within the first year of their marriage, and some of his most

poignant songs, including the hauntingly beautiful ‘‘What’ll I Do,’’

‘‘Always,’’ and ‘‘Remember’’ were written for his second wife, the

heiress Ellin Mackay.

Berlin died on September 22, 1989 in New York City. His long,

remarkable life seemed to illustrate that the American Dream was

achievable for anyone who had a vision. He had received awards

ranging from an Oscar to a Gold Medal ordered by President Dwight

D. Eisenhower. He had become an icon of American popular music,

rich and successful, and had helped shape the evolution of that genre

through his use and adaptation of a variety of styles, despite a lack of

education and formal training. Many of his songs had become an

integral part of the tapestry of American life, accompanying repre-

sentative scenes ranging from the idealized world of elegant dances

by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to the humble family fireside

Christmas. It was his role as the spokesman of the American people as

a collective whole—his ability to give voice to their fears, regrets, and

hopes in a most compelling way—that constituted his great contribu-

tion to popular culture of the century.

—Linda Ann Martindale

F

URTHER READING:

Bergreen, Laurence. As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin.

New York, Viking Penguin, 1990.

Ewen, David. Composers for the American Musical Theatre. New

York, Dodd, Mead, 1968.

———. The Story of Irving Berlin. New York, Henry Holt, 1950.

Freedland, Michael. Irving Berlin. New York, Stein and Day, 1974.

Green, Stanley. The World of Musical Comedy. New York, A. S.

Barnes, 1976.

BERNHARDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

231

Irving Berlin

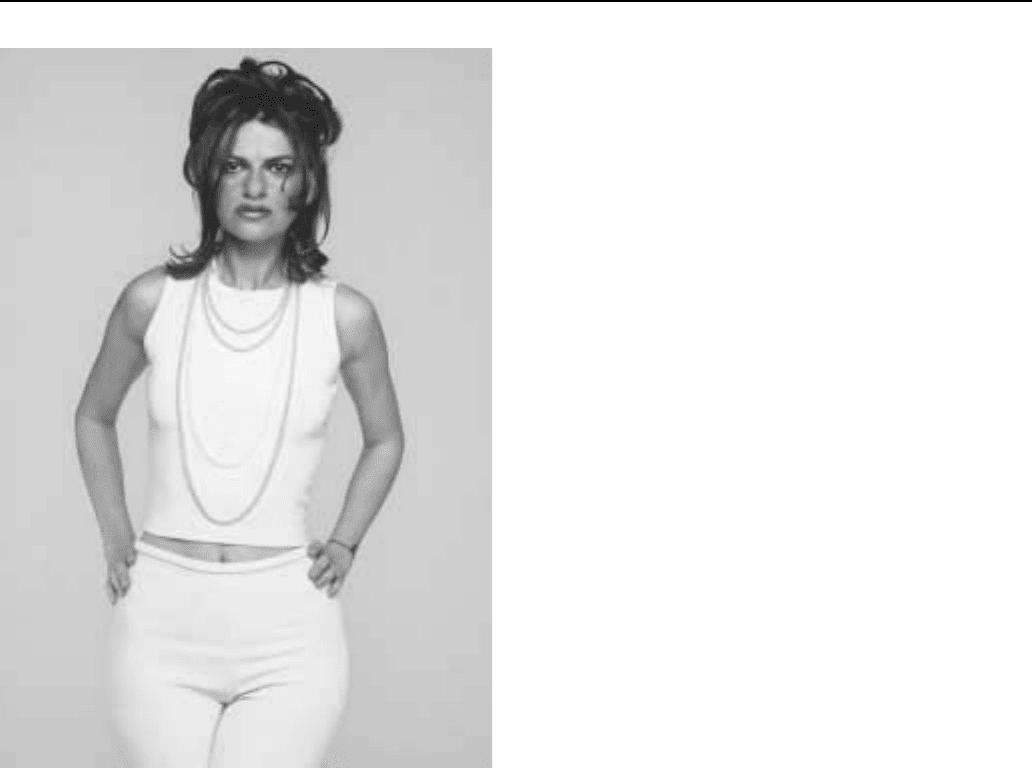

Bernhard, Sandra (1955—)

Sandra Bernhard’s unique appeal derives, in part, from her

resistance to categorization. This Flint, Michigan, native is a comedi-

enne, pop singer, social satirist, and provocateur, often all at the same

time. Her talents—wry humor, offbeat looks, earthy ease in front of

an audience, and powerful singing voice—recall the cabaret and

Broadway-nurtured divahood of Barbra Streisand and Bette Midler;

but while Bernhard has the magnetism of a superstar, she has found

difficulty reaching that peak, insofar as a star is a commodity who can

open a movie, carry a TV show, or sell millions of albums. She has

fashioned a career from the occasional film (Hudson Hawk, 1991) or

TV appearance (Roseanne, Late Night with David Letterman); hu-

morous memoirs (Confessions of a Pretty Lady); a dance album (I’m

Your Woman); and most notably, her acclaimed one-woman stage

shows, Without You I’m Nothing (a film version followed in 1990)

and 1998’s I’m Still Here . . . Damn It! To her fans throughout the

BERNHARD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

232

Sandra Bernhard

1980s and 1990s, Bernhard has been both glamour-girl and truth-

teller; her voice a magical siren’s call from the surly fringes of

mainstream success.

The King of Comedy (1989), the Martin Scorsese film which

introduced Bernhard to the world, encapsulates the entertainer’s

contradictions and special allure. In this dark comedy, Robert DeNiro

and Bernhard play a pair of star-struck eccentrics who hatch a bizarre

plot to kidnap the object of their fantasies, a Johnny Carson-like talk-

show host (Jerry Lewis). As Masha, Bernhard plays her deranged

obsessive compellingly, triumphing as the one bright spot in this

rather sour film, which is widely regarded as one of Scorsese’s lesser

efforts. In it she displays an outsize personality, hilarious comic

delivery, and an undeniable presence, yet instead of offering her a

career in films, Hollywood didn’t seem to know what to make of

Bernhard’s strange gifts (in much the same way that Midler suffered a

dry spell after her stunning debut in The Rose [1979]), and a

mainstream movie career failed to materialize. In the 1990s Bernhard

accepted roles in low-budget independent films such as Inside Mon-

key Zetterland (1993) and Dallas Doll (1995). Television gained her a

wider audience, as with her 1992 HBO special Sandra After Dark.

The performer and the character share the same problem: both

are unnerving in that they expose America’s neurotic preoccupation

with celebrity. As Justin Wyatt writes, ‘‘Bernhard’s film debut as the

maniacal Masha . . . offers a paradigm for the development of her

subsequent career.’’ Bernhard and Masha are not synonymous, yet

they intersect at crucial points: having seized the spotlight by playing

a gangling, fervent girl with stardust in her eyes, Bernhard has

assumed a persona that rests on a love/hate relationship with fame.

Having portrayed a fanatic who, in skimpy underwear, takes off down

a Manhattan street after a star, in her later stage acts Bernhard’s bid

for stardom included facing down her audience in pasties or diapha-

nous get-ups. Finally, after putting her illustrious costar and director

to shame in The King of Comedy as a novice actress, by the late 1990s

Bernhard had become a skilled cult satirist accused of having greater

talents than her world-famous targets.

Onstage, Bernhard is often physically revealed, yet protected

emotionally within a cocoon of irony. Her humor relies on an

exploration of the magical process of star-making, and her own thirst

for this kind of success is just more fodder for her brand of satire. She

both covets fame and mocks it. As New Yorker critic Nancy Franklin

observes, ‘‘It has always been hard to tell where her sharp-tongued

commentary on celebrity narcissism ends and her sharp-tongued

narcissistic celebrity begins.’’ Bernhard’s references to figures in the

entertainment world are trenchant but rarely hateful. When she sets

her sights on various personalities, from Madonna to Courtney Love

to Stevie Nicks, one finds it difficult to separate the envy from the

disapproval, the derision from the adoration, as when she offers her

doting audience the seemingly off-hand remark (in I’m Still Here):

‘‘Tonight, I have you and you and you. And I don’t mean in a Diana

Ross kind of way.’’ She takes Mariah Carey to task for her using

blackness as a commercial pose, and (in Without You I’m Nothing)

gently mocks her idol Streisand, for singing the incongruous lyric to

‘‘Stoney End’’: ‘‘I was born from love and my poor mama worked the

mines.’’ Bernhard casts a doubtful look: ‘‘She worked in the mines?

The diamond mines, maybe.’’

At times one finds it hard to identify her sly anecdotes as entirely

fictional, or as liberal embellishments rooted in a kernel of truth. Even

the seemingly genuine details about palling around with Liza Minnelli or

sharing a domestic scene with Madonna and her baby are delivered in

quotation marks, which is why Bernhard’s art is camp in the truest

sense; if ‘‘the essence of camp,’’ according to Susan Sontag, ‘‘is its

love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,’’ then Bernhard

must qualify as its high priestess. But there’s a catch: she enjoys the

facade almost as much as she enjoys stripping it away.

A few critics find this ambiguity trying, but many more applaud

her ability to negotiate this tightrope successfully. Just as a female

impersonator’s act is comprised of both homage and parody (the

artifice is simultaneously celebration and critique), Bernhard’s take

on fame carries a similarly ambivalent message, its pleasure deriving

from its irresolution. For stardom, this absurdly artificial construct

inspires in the performer deep affection as well as ridicule. She

succeeds in transforming a caustic commentary on fame into a kind of

fame itself, massaging a simulacrum of stardom into bona fide

notoriety. The very tenuousness of her status functions as an asset—

indeed, the basis—for what New York Times critic Peter Marks called

her ‘‘mouth-watering after-dinner vitriol,’’ as he recommended her

show to anyone ‘‘who’s fantasized about taking a trip to the dark side

of People magazine.’’

—Drew Limsky

BERRAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

233

FURTHER READING:

Bernhard, Sandra. Confessions of a Pretty Lady. New York, Harper &

Row, 1988.

Chua, Lawrence. ‘‘Guise and Dolls: Out and About with Sandra

Bernhard.’’ Village Voice. February 6, 1990, 6.

Franklin, Nancy. ‘‘Master of Her Domain.’’ New Yorker. November

16, 1998, 112-113.

Marks, Peter. ‘‘Comedy Whose Barbs Just Won’t Go Away.’’ The

New York Times. November 6, 1998, E3.

Sontag, Susan. ‘‘Notes on Camp.’’ Against Interpretation. New

York, Anchor, 1986, 275-292.

Wyatt, Justin. ‘‘Subversive Star-Making: Contemporary Stardom and

the Case of Sandra Bernhard.’’ Studies in Popular Culture. Vol.

XIV, No. 1, 1991, 29-37.

Bernstein, Leonard (1918-1990)

After his sensational 1943 debut with the New York Philhar-

monic, conductor Leonard Bernstein overnight became an American

folk hero with a mythic hold on audiences. His rags-to-riches story

particularly appealed to a nation emerging from the Depression and

learning about the Holocaust.

Raised in a Hasidic home, Bernstein attended Harvard and

seemed the quintessential Jewish artist struggling against obscurity

Leonard Bernstein

and prejudice. His compositions for the musical theater, such as West

Side Story, became classics, and his classical compositions became

welcome additions to orchestral repertories. He was hailed by mass

audiences for demonstrating that it was possible to treasure the old

while welcoming the new.

Lenny, as Bernstein was popularly known, turned frequent

television appearances into ‘‘Watch Mr. Wizard’’ episodes to explain

classical music. College teachers claimed that he was not an original

thinker and that many of his statements were oversweeping. Nonethe-

less, untold hundreds of thousands of admirers would continue to

revere him, long after his death.

—Milton Goldin

F

URTHER READING:

Secrest, Meryle. Leonard Bernstein: A Life. New York, Knopf, 1994.

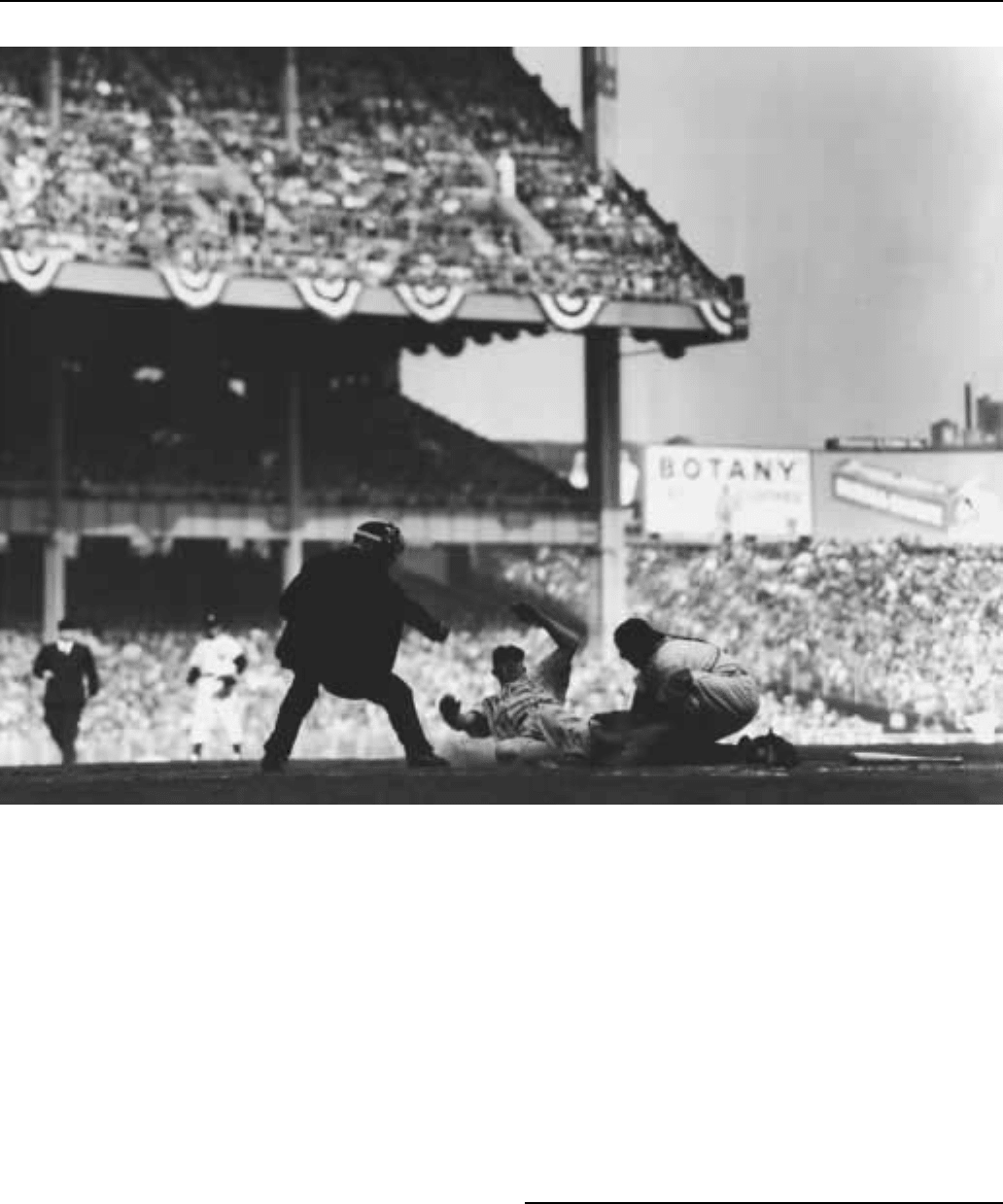

Berra, Yogi (1925—)

Lawrence ‘‘Yogi’’ Berra is one of the most loved figures of the

sporting world. The star catcher for the great New York Yankee

baseball teams of the mid-twentieth century, he has built a legacy as a

dispenser of basic wisdom worthy of his nickname.

Born to Italian immigrants in the ‘‘Dago Hill’’ neighborhood of

St. Louis, Missouri, Berra acquired his moniker as childhood friends

remarked that he walked like a ‘‘yogi’’ snake charmer they had seen

in a movie. He grew up idolizing future Hall of Fame outfielder Joe

‘‘Ducky’’ Medwick of the St. Louis Cardinals, and as a teenager left

school to play baseball with his friend Joe Garagiola. Cardinals

General Manager Branch Rickey signed Garagiola for $500, but did

not think Yogi was worth the money. A scout for the New York

Yankees did, however, and Yogi started playing catcher in their farm

system, until he turned 18 and the navy intervened.

After participating in D-Day and other landings, Berra returned

to the United States and the Yankee farm club. He was noticed and

promoted to the Yankees in 1946 after manager Mel Ott of the rival

New York Giants offered to buy his contract for $50,000. At the time,

Yankees general manager Larry McPhail said of Yogi’s unique

stature that he looked like ‘‘the bottom man on an unemployed

acrobatic team.’’ Jaded Yankee veterans and the New York press

were soon amused to no end by his love for comic books, movies, and

ice cream, and knack for making the classic comments that would

come to be known as ‘‘Berra-isms’’ or ‘‘Yogi-isms.’’ One of the first

came in 1947 when a Yogi Berra Night was held in his honor. Berra

took the microphone and stated, ‘‘I want to thank all those who made

this night necessary.’’

Many more sayings were to follow over the years. He described

his new house thusly: ‘‘It’s got nothing but rooms.’’ When asked why

the Yankees lost the 1960 World Series to the Pittsburgh Pirates, Yogi

answered, ‘‘We made too many wrong mistakes’’ (a quote later

appropriated by George Bush in a televised debate). Asked what time

it is, he replied, ‘‘Do you mean now?’’ Some sayings simply

transcended context, zen-fashion: ‘‘You see a lot just by observing.’’

‘‘If the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be.’’ ‘‘When you get to a fork in

the road, take it.’’ After a time interviewers began making up their

BERRY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

234

Yogi Berra (right) blocking home plate.

own quotes and floating them as ‘‘Yogi-isms.’’ Stand-up comedians

and late-night talk show hosts followed soon after.

A sensitive man, Yogi often seemed genuinely hurt by willful

misquotes and jokes about his appearance and intelligence, but his

serene nature triumphed in the end. He was also a determined

competitor who could silence critics with clutch performances. In

1947, he would hit the first pinch-hit home run in World Series history

as the Yankees beat the Brooklyn Dodgers. When Casey Stengel, a

character in his own right, became the Yankee manager in 1949, Yogi

gained a valuable ally and soon developed into the best catcher of the

time, along with Dodger Roy Campanella. He would go on to set

World Series records for games played and Series won, as well as

leading in hits, doubles, and placing second behind Mickey Mantle in

home runs and runs-batted-in (RBIs). Later, as a manager himself, he

would lead the Yankees in 1964 and the New York Mets in 1973 to the

World Series. Yogi was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.

Managing the Yankees again in 1985, he would be fired after

standing up to tyrannical Yankee owner George Steinbrenner, an

achievement some would liken to a World Series in itself. After not

speaking for 14 years, a period during which Berra would not visit

Yankee Stadium even when his plaque was erected in centerfield, the

pair would suddenly reconcile in early 1999. As Yogi had said about

the 1973 Mets pennant drive, ‘‘It ain’t over ’til it’s over.’’

—C. Kenyon Silvey

F

URTHER READING:

Berra, Yogi, with Tom Horton. Yogi: It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over. New

York, McGraw-Hill, 1989.

Okrent, Daniel, and Steve Wulf. Baseball Anecdotes. New York,

Harper & Row, 1989.

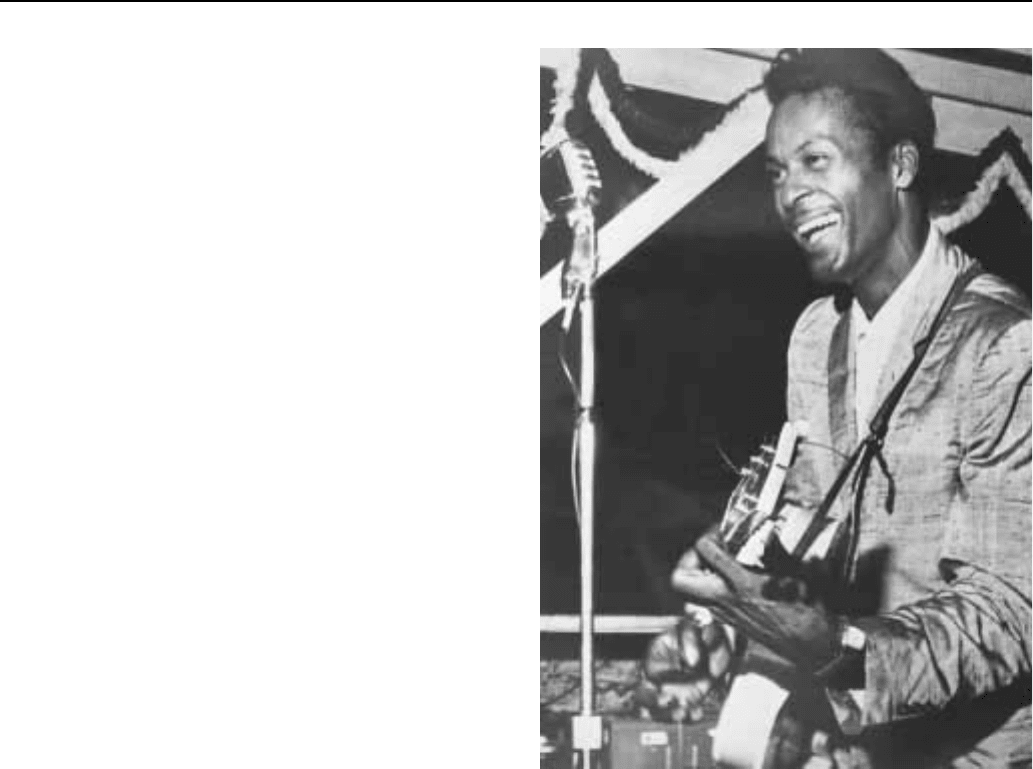

Berry, Chuck (1926—)

Singer, songwriter, and guitarist Charles Edward Anderson

Berry, better known as Chuck Berry, epitomized 1950s rock ’n’ roll

through his songs, music, and dance. ‘‘If you tried to give rock ’n’ roll

another name, you might call it ‘Chuck Berry,’’’ commented John

Lennon, one of the many artists influenced by Berry’s groundbreaking

BERRYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

235

works—others included the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys. A

consummate showman with an electrifying stage style, he originated

such classic songs as ‘‘School Days,’’ in which he proclaimed ‘‘hail,

hail, rock and roll’’ and ‘‘long live rock and roll’’; and ‘‘Rock and

Roll Music,’’ in which he sang: ‘‘It’s gotta be rock and roll music, if

you want to dance with me.’’ Berry was the first black rock ’n’ roll

artist to cross the tracks and draw a significant white audience to his

music. His career was sidetracked, however, with his arrest and

imprisonment on morals charges in 1959.

Berry captured the exuberant teenage spirit of the 1950s in his

music. In the early part of that decade, the precursors of white rock ’n’

roll and the purveyors of black rhythm and blues lived on opposite

sides of the tracks, with the music of each being played on small radio

stations for their respective audiences. Berry combined black rhythm

and blues, white country music, jazz, and boogie woogie into his

style, and his music and lyrics became the catalyst for the music of the

Rolling Stones, Beatles, and Beach Boys. His composition ‘‘Nadine’’

was a mirror of the later style of the Rolling Stones. Berry’s ‘‘Sweet

Little Sixteen’’ was adapted as ‘‘Surfin’ USA’’ by the Beach Boys,

becoming a million dollar single.

Berry was born on October 18, 1926 in St. Louis, Missouri.

(Some sources attribute San Jose, California as his place of birth

based on false information he originally gave his longtime secretary

for a biographical sketch.) As a teenager, Berry was interested in

photography and poetry, until he began performing. He came from a

good home with a loving mother and father but strayed from his home

training, first encountering the juvenile-justice system for a bungled

armed robbery, serving two years in reform school. Upon his release

in 1947, Berry returned home and began work at General Motors

while taking up hair dressing and cosmetology. By 1950, he was

married with two children and had formed a trio with pianist Johnny

Johnson and drummer Ebby Harding. Their group played at the

Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, Illinois, gaining a considerable

reputation in the surrounding area. He also studied and honed his

guitar technique with a local jazz guitarist named Ira Harris. The trio

played for a largely black audience, but with the drop of a cowboy hat,

Berry could switch to country and hillbilly tunes.

Berry traveled to Chicago in 1955, visiting bands and inquiring

about recording. Muddy Waters suggested that he contact Leonard

Chess, president of Chess records. A week later, Berry was back in

Chicago with a demo and subsequently recorded ‘‘Maybellene’’

(originally called ‘‘Ida Mae’’) which rose to the number one spot on

the R&B chart and number five on the pop chart. Almost instantane-

ously, Berry had risen from relative regional obscurity to being a

national celebrity with this crossover hit. From 1955 to 1960, Berry

enjoyed a run of several R&B top-20 entries with several of the songs

crossing over to the pop top-10. ‘‘Thirty Days,’’ ‘‘Roll Over Beetho-

ven,’’ ‘‘Too Much Monkey Business,’’ ‘‘School Days,’’ ‘‘Rock and

Roll Music,’’ ‘‘Sweet Little Sixteen,’’ ‘‘Johnny B. Goode,’’ and

‘‘Almost Grown’’ were not only commercial successes but well

written, engaging songs that would stand the test of time and

become classics.

Berry’s musical influences were diverse. Latin rhythms are

heard in ‘‘Brown-Eyed Handsome Man’’ and in ‘‘Rock and Roll

Music’’; black folk-narrative styles in ‘‘Too Much Monkey Busi-

ness’’; polka and the Italian vernacular in ‘‘Anthony Boy’’; the black

folk-sermon and congregational singing style in ‘‘You Can’t Catch

Me’’; blues à la John Lee Hooker in ‘‘Round and Round’’; and

country music in ‘‘Thirty Days.’’ Instrumentally, his slide and single

string work was influenced by Carl Hogan, guitarist in Louis Jordan’s

Chuck Berry

Tympany Five combo; and by jazz guitarist Charlie Christian and

blues guitarist Aaron ‘‘T-Bone’’ Walker, whose penchant for repeat-

ing the same note for emphasis influenced Berry. Nat ‘‘King’’ Cole

influenced Berry’s early vocal style, and Charles Brown’s influence

is evident in ‘‘Wee Wee Hours.’’ Berry makes extensive use of the

12-bar blues form. He occasionally departs from the blues form with

compositions such as ‘‘Brown-Eyed Handsome Man,’’ ‘‘Thirty Days,’’

‘‘Havana Moon,’’ ‘‘You Can’t Catch Me,’’ ‘‘Too Pooped to Pop,’’

and ‘‘Sweet Little Sixteen.’’ Berry makes extensive use of stop time

as in ‘‘Sweet Little Sixteen,’’ creating a tension and release effect.

Berry was a featured performer on Alan Freed’s radio programs

and stage shows and appeared in the films Go Johnny Go, Mister Rock

and Roll, Rock, Rock, Rock, and Jazz on a Summer’s Day. He also

appeared on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Berry toured as a

headliner on bills with artists such as Carl Perkins, Bill Haley and the

Comets, and Little Richard, among others.

His recording success turned Berry into a wealthy businessman

and club owner, and a developer of his own amusement park. His

quick rise to fame and his robust appetite for women of all races

caused resentment among some whites. In 1959 he allegedly trans-

ported a fourteen-year-old Spanish-speaking Apache prostitute across

state lines to work as a hat checker in his night club outside of St.

Louis. Berry fired her and she protested. A brazenly bigoted first trial

BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

236

ensued and was dismissed, but in the second trial, Berry was convict-

ed and sent to prison, serving two years of a three-year sentence. This

experience left him extremely embittered, with his marriage ruined.

While he survived financially, he became inward, distrustful, and

suspicious of people.

By the time Berry was released in 1964, the British Invasion with

the Beatles and Rolling Stones was in full force; both groups included

Berry’s songs on their albums. He continued to tour, often with pick-

up bands. In 1966, he left Chess Records to record for Mercury, an

association that did not yield any best sellers. He returned to Chess in

1971 and had his first gold record with ‘‘My Ding-a-Ling,’’ a

whimsical, double entendre-filled adaptation of Dave Bartholomew’s

‘‘Toy Bell.’’ In 1972, Berry appeared as a featured attraction in Las

Vegas hotels. By 1979, he had run afoul with the law again and was

sentenced to four months and one thousand hours of community

service for income tax evasion.

During his incarceration in Lompoc, California, he began work

on Chuck Berry: the Autobiography, a book that made extensive use

of wordplay, giving insight into his life, romances, comebacks, and

context for his songs. For his sixtieth birthday celebration, in 1986, a

concert was staged in conjunction with a documentary filming of

Chuck Berry: Hail, Hail, Rock and Roll by producer Taylor Hackford.

The film featured an all-star cast of rock and R&B artists, including

Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones as musical director, plus Eric

Clapton, Linda Ronstadt, Robert Cray, Etta James, and Julian Lennon.

In 1986, Berry was inducted into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

His importance as a songwriter, guitarist, singer, innovator and

ambassador of that genre remains unquestioned. To paraphrase one of

his lines in ‘‘Roll Over Beethoven,’’ Berry’s heart beats rhythm and

his soul keeps on singin’ the blues.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Berry, Chuck. Chuck Berry: The Autobiography. New York, Harmo-

ny Books, 1987.

De Witt, Howard A. Chuck Berry: Rock ’n’ Roll Music. Fremont,

California, Horizon, 1981.

The Best Years of Our Lives

A 1946 film that perfectly captures the bittersweet sense of post-

World War II American society, The Best Years of Our Lives

examines three war veterans as they adjust to new stateside roles.

Former sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March), disillusioned with

his banking career, develops a drinking problem but learns to control

it with the support of his wife Milly (Myrna Loy) and adult daughter

Peggy (Teresa Wright). Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), one-time soda

jerk and bombadier, finds that his wartime skills are now useless and

eventually leaves his self-centered wife Marie (Virginia Mayo) for

Peggy. Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), an ex-sailor who lost his

hands in a shipboard accident, learns to deal with the rudeness of well-

meaning civilians and shapes a new life with his fiancée Wilma

(Cathy O’Donnell). A much-honored film (it won eight Oscars,

including Best Picture), Best Years is a beautiful, simple, and elo-

quent evocation of postwar America.

—Martin F. Norden

F

URTHER READING:

Anderegg, Michael A. William Wyler. Boston, Twayne, 1979.

Gerber, David A. ‘‘Heroes and Misfits: The Troubled Social

Reintegration of Disabled Veterans in The Best Years of Our

Lives.’’ American Quarterly. Vol. 24, No. 4, 1994, 545-74.

Kern, Sharon. William Wyler: A Guide to References and Resources.

Boston, G. K. Hall, 1984.

Norden, Martin F. The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical

Disability in the Movies. New Brunswick, Rutgers University

Press, 1994.

Bestsellers

As a group bestsellers conjure an image of lowbrow literature, of

escapist fiction—bodice rippers, multi-generation epics, courtroom

melodramas, and beach novels. Although books of all sorts, including

nonfiction, cartoon anthologies, and genuine literature routinely

make the bestseller lists in America, bestsellers have always been

dismissed as popular reading. In 80 Years of Best Sellers authors

Alice Payne Hackett and James Henry Burke assert that, ‘‘Best-

selling books are not always the best in a critical sense, but they do

offer what the reading public wants,’’ and the truth is that bestseller

status is more often associated with Danielle Steele than Sinclair

Lewis, even though both have published best-selling novels.

Tracking and reporting the best-selling books in America offi-

cially began in 1895. Publishing of all sorts experienced a boom in the

1890s for a variety of reasons, including cheaper paper, substantial

improvements in the printing press, a high literacy rate, better public

education systems, and an increase in book stores and public libraries.

Popular tastes were also shifting from educational books and other

nonfiction to works of fiction; an 1893 survey of public libraries

showed that the most frequently borrowed books were novels, which

at that time were largely historical fiction with overtones of adven-

ture, e.g. The Last of the Mohicans, Lorna Doone, The House of the

Seven Gables. The first list of best-selling novels in America ap-

peared in a literary magazine titled The Bookman in 1895. The best-

selling novel that year was Beside the Bonnie Brier Bush by one Ian

Maclaren. Although the phrase ‘‘best seller’’ was not used by The

Bookman at this time; it seems to have been coined about a decade

later by Publishers Weekly in an interview with a successful book

dealer. Bookman referred to the novels on its first list as being sold

‘‘in order of demand’’ and started referring to ‘‘Best Selling Books’’

in 1897. Publishers Weekly began to run its own list of bestsellers in

1912, by which time the term was in general usage. The first several

bestseller lists were dominated by European novels, with an average

of only two or three American novels per year. While many European

authors were undoubtedly popular with American readers and Euro-

pean settings were more glamorous, the primary reason that there

were few highly successful American novelists was U.S. copyright

law, which prior to 1891 had made it far less expensive to publish

books written by Europeans than by Americans.

BESTSELLERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

237

The existence of bestseller lists had an immediate effect on

American publishers, who began to devise ways to promote their

novels and ensure them bestseller status. The novel The Honorable

Peter Stirling, written by Paul Leceister Ford and published in 1897,

was selling very poorly until its publisher spread rumors that the book

was based on President Grover Cleveland; the book saw a drastic

increase in readership and 228,000 copies were sold that year. The

1904 novel The Masquerade was the first book to be published

without an author credit; speculation as to who ‘‘anonymous’’ might

be—it was novelist Katherine Cecil Thurston—increased public

awareness of the novel and it was one of the top ten sellers of its year.

The gimmick of publishing an anonymous book was used repeatedly

throughout the century; the success of Primary Colors in 1996

indicates that it has remained an effective marketing device.

Two significant literary genres made their first appearances on

the list in 1902. Owen Wister’s The Virginian—which became a

genuine publishing phenomenon over time, remaining continuously

in print for over thirty years—was at the height of its success in 1902.

Booksellers were ordering one thousand copies per day. The Virginian

created a market for western novels; western fiction became a staple

of the list when Zane Grey’s The Lone Star Ranger was published in

1915 and the western audience has never truly disappeared. Arthur

Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles was not just the first

Sherlock Holmes book to achieve bestseller status but was the first

work of detective fiction to do so as well. The first American suspense

novelist to reach the year’s top ten list was Mary Roberts Rinehart in

1909. Not all turn of the century bestsellers were escapist fiction,

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, the famous muckraking exposé of the

American meat packing industry, became a bestseller in 1906.

When Publishers Weekly began publishing its own list of

bestsellers in 1912, it separated nonfiction from fiction. A third

category, simply titled ‘‘war books,’’ was added for the duration of

World War I. Books about the European conflict sold extremely well

and appear to have created a larger market for nonfiction reading in

general, since sales of nonfiction books increased in post-World War

I America. A similar increase occurred after World War II, when self-

help books began to appear regularly on the bestseller lists. Emily

Post’s Etiquette, first published in 1923, demonstrated that a nonfic-

tion bestseller can be recognized as a definitive reference source and

remain in print almost indefinitely

Since the 1910s, bestseller status has been determined in the

same way. Several publications, most notably Publishers Weekly and

more recently the New York Times Book Review, publish weekly lists

of the ten best-selling fiction and nonfiction books in America. The

lists originally referred only to cloth, or hardbound, books; separate

lists for paperbacks were added in the 1960s. Information is gathered

from book stores around the United States, so the list of bestsellers

does refer to books sold, not just books distributed (as was the case

with the record industry for decades). Because most books stay on the

list for multiple weeks, approximately forty-five to fifty books reach

either list per year. The method of determining which books are

bestsellers has been criticized. The lists reflect what is selling well at

any given week, so that a book that sold slowly but steadily, such as

The Betty Crocker Cookbook, which is one of the highest selling

books of all time, might never appear on a bestseller list. Likewise, it

is possible for an author to sell millions of books during a career

without ever having one be designated a bestseller. Most of the sales

figures are gathered from larger book stores so that smaller stores,

which frequently have more literary clientele, have little input into the

lists. Substantial advance publicity from a publisher can almost

certainly boost sales for a week or two, creating an artificial bestseller.

Finally, book club editions are not taken into account when compiling

the lists; the Book of the Month Club and the Literary Guild, founded

in 1926 and 1928 respectively, have accounted for a large percentage

of book sales each year, as have many other book clubs and mail order

sources, all without being included in the bestseller statistics. Still, the

bestseller lists remain a fairly accurate barometer of what America is

reading at any given time.

Even by the 1920s, certain patterns were beginning to emerge on

the lists. There was the phenomenon known as ‘‘repeaters’’—authors

who could be counted on to produce one best-selling book after

another. Edna Ferber in the 1930s, Mickey Spillane in the 1950s,

Harold Robbins in the 1960s, and John Grisham in the 1990s were all

repeaters whose publishers knew that practically anything they wrote

would become a bestseller. John O’Hara took the concept of repeating

to its extreme; not only did he write a bestseller every year or two for

most of his career but his publisher, Random House, always released

the book on the same date, Christmas Eve, to build a steady market.

‘‘Repeaters’’ are important to publishers, who need certain and

dependable sales successes, so the practice of paying large advances

to such authors is common and widespread. In contrast to the

repeaters, some authors have only one or two bestsellers and never

produce another. This phenomenon can be hard to explain. Some

authors only produce one novel: Margaret Mitchell never wrote

another after the enormous success of Gone with the Wind; Ross

Lockridge committed suicide shortly after the publication of Raintree

County. But others try to repeat their earlier successes and fail, so that

while someone like Kathleen Winsor may write many books during

her lifetime, only Forever Amber is successful. Bestsellers are very

attuned to popular taste; an author has to be strongly in synch with

national attitudes and concerns to produce a bestseller. After a few

years have passed, author and society might not be so connected.

Another phenomenon may affect both repeaters and authors of

solitary bestsellers: fame for best-selling writers and their books can

be remarkably short-lived. For every Daphne du Maurier, well

remembered years after her death, there is a George Barr McCutcheon;

for every Peyton Place there is a Green Dolphin Street. Decades ago

Rex Beach and Fannie Hurst were household names, each with

multiple bestsellers; someday Dean Koontz and Jackie Collins might

have lapsed into obscurity. Again, this might be attributed to the

popular nature of the bestseller; best-selling novels are frequently so

topical and timely that they tend to become dated more rapidly than

other fiction. They are rarely reprinted after the initial burst of

popularity is over and slip easily from the public memory. Of course,

on some occasions when the novel remains well known the author

might not, so that everybody has heard of Topper but no one

remembers Thorne Smith and everybody is familiar with A Tree

Grows in Brooklyn while few recall it was written by Betty Smith.

Specific genres of books are more likely to become bestsellers

and since the beginning of the bestseller lists, certain categories have

dominated. Among the most common bestseller types are the histori-

cal novel, the roman à clef, the exposé novel, and the thriller.

The first best American bestsellers were long romantic novels

that provided escapist reading to their audiences while appearing to be

at least slightly educational; all were set in the past and most were set

in Europe. Gradually American settings began to dominate, particu-

larly the American frontier, but the historical novel has remained an

extremely popular type of fiction and has changed relatively little

since its earliest appearance. There is usually some romance at the

BETTER HOMES AND GARDENS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

238

core, with complications that keep it from being resolved for hun-

dreds of pages. The novel is often built around a significant historical

event; the Civil War has been an especially popular setting. Great

attention is given to detail and many historical novelists spend years

researching an era before writing about it. Some variations of the

historical novel would include the multi-generational saga, which

follows a family for several decades and generations, such as Ed-

na Ferber’s Cimarron; the religious epic, such as Charles Shel-

don’s In His Steps, a fictionalized life of Christ that introduced the

phrase ‘‘What would Jesus do?’’; and the historical adventure, as

seen in much of Kenneth Roberts’s many fictional accounts of

westward expansion.

Literally ‘‘book with a key,’’ the roman à clef is a work of fiction

that is obviously based on real people; the ‘‘key’’ is determining who

was the inspiration for the novel. Obviously, for the book to be

successful it has to be easy for the reader to guess who it is supposed to

be about; it takes no great deductive ability to realize, for example,

that the presidential widow in Jacqueline Susann’s Dolores is based

on Jacqueline Onassis. Harold Robbins is the most successful author

of the roman à clef, having written about Harold Hughes (The

Carpetbaggers), Lana Turner (Where Love Has Gone), and Hugh

Hefner (Dreams Die First), among others. More literary examples of

the roman à clef include two genuine bestsellers, Sinclair Lewis’s

Elmer Gantry, based on Billy Sunday and Aimee Semple McPherson;

and Robert Penn Warren’s fictionalized account of Huey Long, All

the King’s Men.

The exposé novel examines a major American institution and

purports to tell readers exactly how it works; of course, these novels

always contain copious amounts of sex and intrigue no matter how

dull their subject matter might appear. Arthur Hailey’s Airport, for

example, presents a romantic triangle between a pilot, his wife, and

his pregnant mistress (one of his flight attendants); a bomb on board

the plane; and an emergency landing in a snowstorm. Hailey is the

recognized leader of the exposé novel, having also written Wheels,

Hotel, and The Moneychangers, among others. Some exposé novels

have the added attraction of being written by someone who actually

worked within the industry, giving them an insider’s view which they

presumably pass along to their readers. Joseph Wambaugh, the police

officer turned author is perhaps the best known of these. It has become

fairly common to hire a celebrity to use their name on an exposé

novel, which is then written in collaboration with a more professional

author, as was done with Ilie Nastase’s The Net and model Nina

Blanchard’s The Look.

Ever since The Hound of the Baskervilles, mysteries and sus-

pense novels of some sort have been common on the list. It was not

until the publication of John LeCarre’s The Spy Who Came in from the

Cold in 1964, however, that publishers recognized thrillers as a

popular fiction form. Thrillers can be distinguished from mysteries by

the fact that there is no puzzle to solve; the appeal of the novel lies in

waiting to see what will happen to the characters. Crime novels

like those of Elmore Leonard (Get Shorty) are frequently catego-

rized as thrillers, but so are courtroom novels like John Grisham’s

The Firm and Scott Turow’s Above Suspicion; technology based

works like Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October; Lawrence

Sanders’s (The First Deadly Kiss) and Thomas Harris’s (Silence of

the Lambs) dissections of serial murder; and war novels like Len

Deighton’s Bomber.

Beginning in the 1970s there were fewer privately owned

publishing houses; many have merged and some have been bought

buy larger conglomerates. Bestsellers are now seen as part of a

corporation’s synergy; that is, a best-selling novel is part of a package

that includes movie and/or television adaptations. Television in

particular has proven an avid customer for adaptation rights; as fewer

bestsellers are made into motion pictures, the television medium,

which can provide longer running times that presumably allow more

faithful adaptations, has produced hundreds of made for television

movies and mini-series from best-selling novels. Television’s interest

in the bestseller can be traced to ABC’s highly regarded production of

Irwin Shaw’s Rich Man, Poor Man in 1976. Given the variety of

businesses that may now be contained under one corporate umbrella,

it is not uncommon for one conglomerate to publish a book in

hardcover, publish the paperback edition as well, and then produce

the film or television adaptation. In fact, many publishing houses take

such a possibility into consideration when reviewing manuscripts.

The most popular works within any society would not necessari-

ly be its best; nevertheless, the reading habits of the American public

say much about its culture. If Irving Wallace, Mario Puzo, Janet Daly,

and Leon Uris are not the greatest authors of the twentieth century,

they have still provided millions of readers with a great deal of

pleasure. The best-selling novel might better be evaluated not as a

work of literature but as a significant cultural byproduct, an artifact

that reveals to subsequent generations the hopes and concerns of

the past.

—Randall Clark

F

URTHER READING:

Boca, Geoffrey. Best Seller. New York, Wyndham Books, 1981.

Hackett, Alice Payne and James Henry Burke. 80 Years of Best

Sellers, 1895-1975. New York, Bowker, 1977.

Hart, James D. The Popular Book. Berkely, University of California

Press, 1961.

Sutherland, John. Bestsellers. London, Routledge and Keegan

Paul, 1981.

Better Homes and Gardens

Taking on a snazzy new style, establishing its own website, and

accentuating the acronym BH&G can not alter entirely the role that

Better Homes and Gardens has played in constructing American

ideals of domesticity, home life, and gender roles throughout the

twentieth century. In 1913, Edwin T. Meredith introduced the idea of

a new magazine within an advertisement contained in his magazine,

Successful Farming. The small, discreet ad titled ‘‘Cash Prizes for

Letters about Gardening’’ also made a simple request of readers:

‘‘Why not send fifty cents for a year’s subscription to ‘Garden, Fruit

and Home’ at the same time?’’ In truth no such magazine yet existed;

nor would it be published until 1922. Meredith began publishing

Fruit, Garden and Home before altering the name in 1924 to Better

Homes and Gardens. By facilitating the dialogue that has constructed

the ideal of housing, Better Homes and Garden helped to define

exactly where home and life come together in the American experience.

The impermanence of American life, of course, befuddled many

observers from the nation’s outset. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in the

1830s that ‘‘in the United States a man builds a house in which to

spend his old age and he sells it before the roof is on. . . .’’ A great deal

of interest and attention was paid by upper and upper-middle-class