Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BURLESQUEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

389

A view from the wings of a typical burlesque show.

an appearance by the company soubrette (originally the saucy maid-

servant in French comedy, the term later came to mean a woman who

sang such parts), another comedy skit, a third chorus, some vaudeville

acrobats, and a choral finale with the entire company, reprising the

earlier numbers. A similar but shorter mix followed the intermission.

This would remain the structure of Minsky shows for the next

two decades.

Nor was such entertainment limited to the East Coast. Burlesque

prospered at such houses as the Mutual Theater in Indianapolis, the

Star and Garter in Chicago, and the Burbank Theatre in Los Angeles.

The Columbia Amusement Company, under the leadership of medi-

cine-show veteran Sam Scribner, operated a circuit called the Eastern

Wheel whose chief rival, the Empire Circuit or Western Wheel, it

absorbed in 1913. Scribner managed to balance business instinct and

a personal goal of creating a cleaner act, and for a time the Columbia

Wheel offered what it called ‘‘approved’’ burlesque while competing

with upstart organizations (such as the short-lived Progressive Wheel)

with its own subsidiary circuit called the American Wheel, whose

‘‘standard’’ burlesque featured cooch dancers, comic patter laced

with double-entendre, and runways for the chorus line extending from

the stage out into the audience (an innovation first imported to the

Winter Garden by Abe Minsky, who had seen it in Paris at the Folies

Bergère). The American Wheel offered 73 acts a year, playing to a

total audience of about 700,000 in 81 theaters from New York

to Omaha.

Though Scribner’s quest for clean burlesque ultimately proved

quixotic, he was neither hypocritical nor alone. The founding editor of

Variety, Sime Silverman, took burlesque shows seriously as an art

form, though he too recognized that this was an uphill fight at best,

writing in a 1909 editorial that ‘‘Were there no women in burlesque,

how many men would attend? The answer is the basic principle of the

burlesque business.’’ (Billboard’s Sidney Wire concurred, flatly

asserting in 1913 that ‘‘Ninety percent of the burlesque audiences go

to burlesque to see the girls.’’) This fact was not lost on the Mutual

Circuit, which arose to put Columbia Entertainment out of business in

the 1920s, nor on the Minskys, whose theaters flourished until the

final crackdown on New York burlesque under Mayor Fiorello

LaGuardia and License Commissioner Paul Moss in 1937.

BURMA-SHAVE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

390

Although the leggy chorus line was an indispensable element of

burlesque shows from the start (and would survive them by a half-

century with the perennial Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall) the

cooch dance became a burlesque standard only after promoter Abe

Fish brought Little Egypt and Her Dancers, a troupe of Syrians

specializing in the sexually suggestive ‘‘awalem’’ dances performed

at Syrian weddings, to the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago

in 1893. The transition from cooch dancer to striptease was gradual.

Soubrettes in the earliest days of burlesque often showed off their

youthful bodies even as they sang and danced in solo numbers, but

some, like Rose Sydell of the Columbia Wheel, were star clotheshorses

instead, displaying breathtakingly elaborate costumes on stage.

Still, as the public responded favorably to more flesh and less

clothing as the years wore on, the soubrette’s song-and-dance role

came to be supplanted by the striptease artist. By 1932, according to

Zeidman, there were ‘‘at least 150 strip principals, of whom about 75

percent were new to the industry.’’ The sudden rise in demand for

strippers was partly a corollary of rising hemlines on the street, so

that, as one writer for Billboard pointed out, ‘‘leg shows lost their sex

appeal and, in self-defense, the operators of burlesque shows intro-

duced the strutting strips . . . as far as the police permitted.’’ (Ironical-

ly it was one police raid in 1934, at the Irving Palace Theatre, that

eliminated runways in New York, somewhat to the relief of theater

owners, for whom they were ill suited to the innuendo and soft

lighting effects that were part and parcel of an effective strip act.)

Star strippers included Sally Rand, whose two-fan dance got a

nod in the popular song ‘‘I’m Like a Fish Out of Water,’’ and Gypsy

Rose Lee, who solved the jammed-zipper menace by holding her

costume together with pins which she would remove one by one and

throw to the audience. (Lee would go on to write a mystery novel, The

G-String Murders, and an autobiography, Gypsy, also made into a

movie). Other celebrated strippers included Anna Smith (said to have

been the first to cross the line between above-the-waist nudity and

baring her bottom), Carrie Finnell, Margie Hart, Evelyn Meyers, and

Ann Corio.

By the late 1930s many burlesque shows had ceased to be much

more than showcases for strippers. A burlesque troupe which would

have had one soubrette and a half-dozen comics at the time of the

World War I now often had at least five or six strippers and as few as

two comics and a straight man. In New York, burlesque was effective-

ly put out of business by LaGuardia and Moss by the end of 1937,

although it survived in New Jersey for a few more years in theaters

served by shuttle buses running from Times Square until its mostly-

male audience was called off to war.

Though many performers from the burlesque circuits toured

with the USO during World War II and the Korean conflict, burlesque

itself barely survived into the postwar world, and most houses were

closed for good by the mid-1950s. (Boston’s Old Howard, vacant for

several years, burned beyond repair in 1961.) In 1968 Ann Corio’s

book This Was Burlesque and Norman Lear’s film The Night They

Raided Minsky’s were released, both nostalgic retrospectives on a

vanished era.

Nevertheless, ‘‘legitimate’’ American entertainment, especially

comedy, owed a lasting debt to burlesque throughout most of the

twentieth century, for many of the nation’s stars had either gotten

their start or worked for some time in the genre, including Fannie

Brice, Eddie Cantor, Lou Costello, Joey Faye, W. C. Fields, Jackie

Gleason, Al Jolson, Bert Lahr, Pinky Lee, Phil Silvers, Red Skelton,

and Sophie Tucker. Burlesque enriched America’s vocabulary as

well, with such terms as bump and grind, flash, milking the audience,

shimmy, and yock.

—Nick Humez

F

URTHER READING:

Alexander, H. M. Strip Tease: The Vanished Art of Burlesque. New

York, Knight Publishers, 1938.

Allen, Ralph G. Best Burlesque Sketches. New York, Applause

Theatre Books, 1995.

Allen, Robert C. Horrible Prettyness: Burlesque and American

Culture. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Corio, Ann. This Was Burlesque. New York, Grosset and Dunlap, 1968.

Lear, Norman, producer. The Night They Raided Minsky’s. Culver

City, MGM-UA Home Video, 1990.

Lee, Gypsy Rose. The G-String Murders. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1941.

———. Gypsy/Gypsy Rose Lee. London, Futura, 1988.

Minsky, Morton. Minsky’s Burlesque. New York, Arbor House, 1986.

Scott, David Alexander. Behind the G-String: An Exploration of the

Stripper’s Image, Her Person, and Her Meaning. Jefferson,

McFarland and Company, 1996.

Smith, H. Allen. Low Man on a Totem Pole. Garden City, Doubleday,

Doran & Company, 1941.

Sobel, Bernard. Burleycue: An Underground History. New York,

Farrar & Rinehart, 1931.

Zeidman, Irving. The American Burlesque Show. New York, Haw-

thorn Books, 1967.

Burma-Shave

From 1925 to 1963, a brushless shaving cream called Burma-

Shave became a ubiquitous and much-loved part of the American

scene—not because of the product itself, but because of the roadside

signs that advertised it in the form of humorous poems. Motorists in

43 states enjoyed slowing down to read six signs spelling out the latest

jingle, always culminating in the Burma-Shave trademark. A typical

example might be ‘‘PITY ALL / THE MIGHTY CAESARS / THEY

PULLED / EACH WHISKER OUT / WITH TWEEZERS / BURMA

SHAVE.’’ The inspiration of Burma-Vita, a family-owned business

in Minneapolis, the signs caught the public fancy with their refreshing

‘‘soft sell’’ approach. The uniqueness of the venue was another plus,

and in time the Burma company took to offering jingles that promoted

highway safety and similar public services—still finishing off, how-

ever, with that sixth Burma-Shave sign. Even the public itself was

eventually invited to help create the jingles. The Burma-Shave

phenomenon was a public relations technique without precedent, and

its popularity was reflected in everything from radio comedy sketches

to greeting cards. Though long gone, the Burma-Shave signs remain a

fondly recalled memory of American life in the mid-twentieth century.

In the early 1920s, the Odell family of Minneapolis, Minnesota,

marketed, albeit without much success, a salve which, because key

ingredients came from Burma, they called Burma-Vita. The next

product that they developed was a refinement of brushless shaving

cream, which they naturally dubbed Burma-Shave. The Shave wasn’t

BURNETTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

391

selling much better than the Vita when family member Allan Odell

happened to notice a series of roadside signs advertising a gas

station—‘‘GAS,’’ ‘‘OIL,’’ ‘‘RESTROOMS,’’ etc.—and he had a

brainstorm. ‘‘Every time I see one of these setups,’’ he thought, ‘‘I

read every one of the signs. So why can’t you sell a product that

way?’’ In the autumn of 1925, the Odells drove their first experimen-

tal signposts into the soon-to-be-freezing soil along the side of two

roads outside Minneapolis. These first serial messages were neither

humorous nor poetic—but they worked. For the first time, the Odells

started receiving repeat orders from druggists whose customers

traveled those two highways.

As their business started thriving, the Odells began to develop

the pithy, light-hearted, rhyming jingles for which Burma-Shave

quickly became famous. Hitherto, advertising orthodoxy had stipulat-

ed that most ad-copy should be verbose and serious. Obviously,

verbosity was out of the question when the medium was a series of

roadside signs instead of a magazine page. And the Odells preferred

not to browbeat their potential customers while they were enjoying a

drive in the country. The result was such refreshingly unpretentious

verse as the following: ‘‘DOES YOUR HUSBAND / MISBEHAVE /

GRUNT AND GRUMBLE / RANT AND RAVE / SHOOT THE

BRUTE SOME / BURMA-SHAVE.’’ Or: ‘‘THE ANSWER TO / A

MAIDEN’S / PRAYER / IS NOT A CHIN / OF STUBBY HAIR /

BURMA-SHAVE.’’ It was discovered that the time it took a driver to

go from one sign to the next afforded him more seconds to absorb the

message than if he were reading an ad in a newspaper. What’s more,

as Alexander Woollcott pointed out, it was as difficult to read just one

Burma-Shave sign as it was to eat one salted peanut. And the

humorous content, so unlike the common run of dreary ad copy,

further served to endear the signs to the driving public. Families

would read them aloud, either in unison or with individual members

taking turns.

Eventually the Burma-Shave jingles were as universally recog-

nized as any facet of contemporary Americana. A rustic comedian

could joke about his hometown being so small that it was located

between two Burma-Shave signs. The signs themselves often figured

in the radio sketches of such notable funnymen as Amos n’ Andy,

Fred Allen, Jimmy Durante, and Bob Hope. The popularity of the

signs encouraged the Odells to devote a certain portion of their jingles

each year to such public service causes as fire prevention and highway

safety, as in: ‘‘TRAIN APPROACHING / WHISTLE SQUEALING

/ PAUSE! / AVOID THAT / RUN-DOWN FEELING!’’ Eventually,

the public was brought into the act via heavily promoted contests that

invited people to come up with their own jingles, many of which were

bought and used. Often, the attention given the signs in the media

amounted to free public relations and goodwill for the Burma-

Shave company.

Ironically, one of the greatest instigators for free publicity was

the company’s announcement in 1963 that they would be phasing out

the signs. Although this news was greeted by a wave of national

nostalgia, the fact was that the Burma-Vita company—one of the last

holdouts against corporate takeovers—had finally allowed itself to be

absorbed into the Phillip Morris conglomerate, and they could no

longer justify the expense of the signs in light of the decreasing return

on its advertising investment. It was simply a different world than the

one in which the Burma-Shave signs had been born, and it was time to

retire them gracefully. While it lasted, their fame had seemed all

pervasive. As one 1942 jingle put it: ‘‘IF YOU / DON’T KNOW /

WHOSE SIGNS / THESE ARE / YOU CAN’T HAVE / DRIVEN

VERY FAR / BURMA-SHAVE.’’ That the mythos of Burma-Shave

has outlasted the physical reality of the signs is evidenced in the fact

that they are still being parodied and imitated to this day—and,

whenever this is done, people still get the joke.

—Preston Neal Jones

F

URTHER READING:

Rowsome, Frank. The Verse by the Side of the Road: The Story of the

Burma-Shave Signs and Jingles. New York and Brattleboro,

Vermont, Stephen Greene Press, 1965.

Vossler, Bill. Burma-Shave: The Rhymes, The Signs, The Times. St.

Cloud, Minnesota, North Star Press, 1997.

Burnett, Carol (1933—)

One of the best-loved comedians of the twentieth century, Carol

Burnett set the standard for the variety shows of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Carol Burnett Show (1967-1979) offered a blend of music and

comedy and showcased the popular stars of the period. The highlight

of the show for many, however, was the opening when Burnett

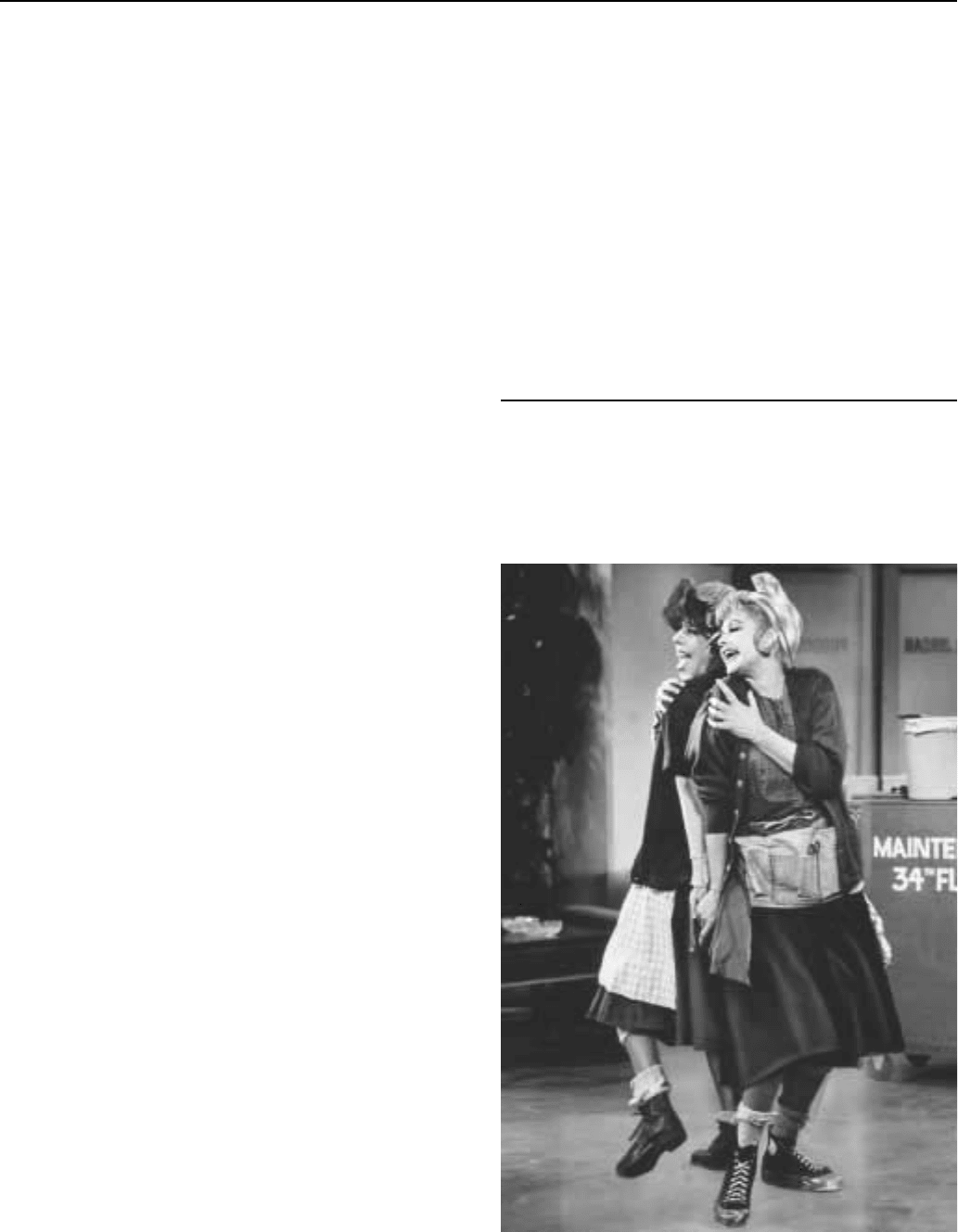

A scene from The Carol Burnett Show.

BURNS AND ALLEN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

392

answered questions from her audience. A number of her characters

have become legend, including the char lady, Eunice, Norma Desmond,

and the gum-chewing, wise-cracking secretary. Perhaps the most

memorable skit of the series took place when Burnett played Scarlet

O’Hara to Harvey Korman’s Rhett Butler. Decked out in her green

velvet curtains, complete with rods, Carol Burnett demonstrated why

she is the queen of comedy. The Eunice skits may have been closer to

Burnett’s own roots than any of the others, allowing her to laugh at the

painful memory of growing up with alcoholic parents and being

constantly torn by the constant bickering of her mother and the

beloved grandmother who raised her. The role of Mama in the Eunice

skits was played by Vicki Lawrence, who won her place on the

Burnett show because of her resemblance to Burnett. After the show

went off the air, Lawrence continued the role in Mama’s Family

(1983-90) and was occasionally visited by Burnett.

Carol Burnett was born on April 26, 1933, in San Antonio,

Texas. Her parents left her with Nanny, her maternal grandmother,

and moved to Hollywood, seeking success, which proved to be

elusive. In her autobiography, One More Time: A Memoir by Carol

Burnett, Burnett traces a history of poverty, disillusionment, and

enduring love growing up in a family that could never seem to deal

with reality. She talks of ‘‘Murphy,’’ a folding bed that was never

folded, as if it were a player in the drama that made up her family life.

Perhaps it was. It represented stability for her, since the bed frequently

contained her grandmother, the most significant influence on her life.

Upon graduating from high school, Burnett had few hopes of realiz-

ing her dream of attending UCLA to pursue an acting career, when an

envelope containing $50 mysteriously showed up in her mail box.

Years later when she wanted to move to New York to pursue a

Broadway career, another benefactor loaned her $1000 with the

stipulations that she pay it back in five years and that she help others

who needed it. The move to New York was fortuitous for Burnett,

allowing her to move both herself and her younger sister toward a

more stable, affluent lifestyle.

Burnett married Don Soroyan, her college boyfriend, in 1955

while striving for success in New York. As her career blossomed, his

did not, and they divorced in 1962. Burnett had achieved her dream of

playing Broadway in 1959 with Once Upon A Mattress, but it was

television that would prove to be her destiny. She began by winning

guest shots on variety shows, such as The Steve Allen Show and The

Garry Moore Show. Her big break came when she was invited to sing

her comedic rendition of ‘‘I Made A Fool of Myself Over John Foster

Dulles’’ on The Ed Sullivan Show. Dulles, of course was the sedate,

acerbic Secretary of State at the time. When Garry Moore won a spot

on the prime time roster, he invited Burnett to come along; she

appeared regularly on his show from 1959 to 1962. She won an Emmy

in 1962, and after that there was no stopping her. In 1963 she married

producer Joe Hamilton, with whom she had three daughters: Carrie,

an actress, Jodie, a businesswoman, and Erin, a homemaker and mom.

Even though Burnett and Hamilton divorced, they remained close

until his death.

Carol Burnett was never afraid to fight for what was important to

her. As a young actress told to call agents and producers after she was

‘‘in something,’’ she put on her own show. As an established actress,

she successfully sued the tabloid, The National Enquirer, for claiming

she was drunk in public. As a mother, she publicly fought to rescue

one of her daughters from drug addiction, and she generously shared

her pain and frustration with others, trying to help those in similar

situations or who were likely to be so. Burnett continues to battle for a

number of charitable causes, including AIDS.

Despite her assured place in the field of comedy, Carol Burnett

broke new ground with such dramatic roles as the mother of a slain

soldier in television’s Friendly Fire (1979). She won critical acclaim

for her hilarious turn as Mrs. Hannigan in the movie version of Annie

(1982). Thirty-five years after winning her first Emmy on The Garry

Moore Show, Burnett won an Emmy for her portrayal of Jamie

Buchman’s mother in the popular television series, Mad About You.

In 1998 Burnett returned to television playing opposite Walter

Matthau in The Marrying Fool. After almost four decades in televison,

Carol Burnett remains an integral part of the American psyche and an

enduring memorial to television’s ‘‘Golden Years.’’

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Burnett, Carol. One More Time: A Memoir by Carol Burnett. Thorndike,

Maine, Thorndike Press, 1986.

Carpozi, George. The Carol Burnett Story. New York, Warner

Books, 1975.

Burnett, Chester

See Howlin’ Wolf

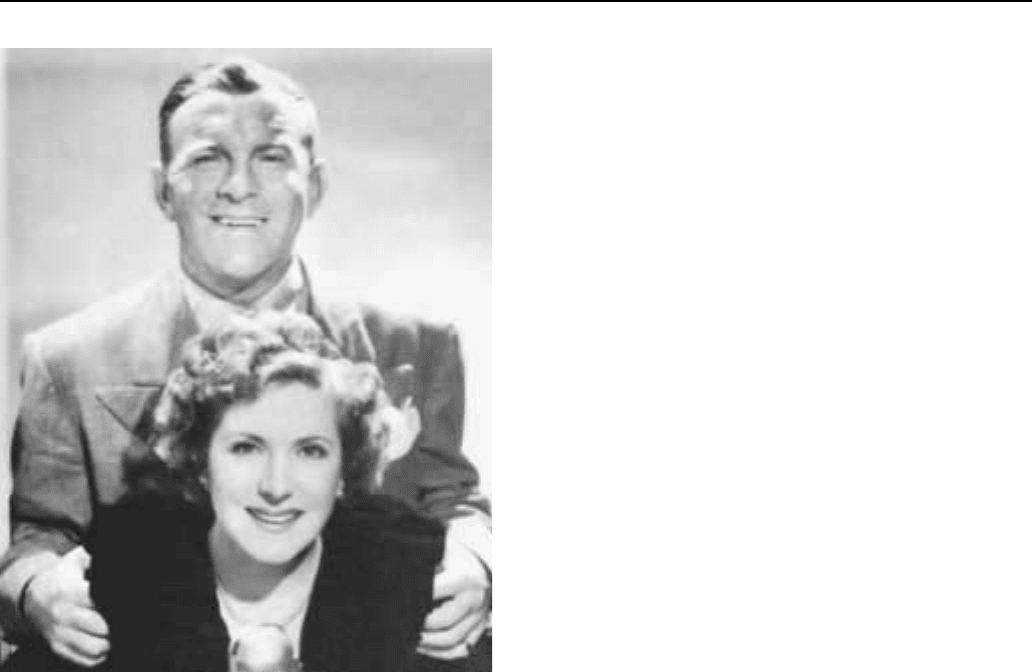

Burns, George (1896-1996), and

Gracie Allen (1895-1964)

George Burns and Gracie Allen formed one of the most re-

nowned husband and wife comedy teams in broadcasting throughout

the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. The cigar-chomping Burns played

straight man to Allen’s linguistically subversive and enchantingly

ditzy housewife in a variety of entertainment media for thirty-five

years. After meeting in 1923 and performing their comedy routine on

the vaudeville circuit and in a few movies, the team reached its

professional peak in broadcasting, first on radio and then on televi-

sion. Their Burns and Allen Show on CBS television from 1950 to

1958 proved particularly innovative as it contained sitcom plots that

were bracketed by Burns’s vaudeville-inspired omniscient narration

and monologues. Their act seemed to be a caricature of their offstage

marriage and working relationship, and the duo openly courted the

conflation. After Allen died in 1964, Burns eventually continued his

career on his own in films and on television specials, but he never

quite got over losing Gracie. He lovingly incorporated his late wife in

his performances and best-selling memoirs, as if encouraging Allen to

remain his lifelong partner from beyond the grave.

Allen was, quite literally, born into show business. Her father,

George Allen, was a song-and-dance man on the West Coast who,

upon retirement, taught dance and gymnastics in a homemade gym in

his backyard. The youngest daughter in the San Francisco-based

Scottish/Irish family of six, Allen first appeared on stage at the age of

three singing an Irish song for a benefit. Her older sisters became

accomplished dancers and while on the vaudeville circuit would

occasionally include Gracie in their act. Gracie’s true gift however,

lay not in song and dance, but in comedy. Recognizing this, she began

to play the fool for her sisters and then as a ‘‘Colleen’’ in an Irish act.

BURNS AND ALLENENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

393

George Burns and Gracie Allen.

Burns also started his career as a child performer. Following a

fairly typical rags-to-riches story of a vaudevillian headliner, Burns

(born Nathan Birnbaum) was the son of a poor Austrian Jewish family

in New York’s Lower East Side. As a small child he performed for

pocket change on street corners and saloons in the neighborhood,

eventually forming a child act, the Pee Wee Quartet, when he was

seven years old. Working in small-time vaudeville by the time he was

a teenager, the aspiring vaudevillian joined a number of comedy

teams under various names including Harry Pierce, Willie Delight,

Nat Burns, and finally, George Burns.

In 1923, Allen and Burns met in Union Hill, New Jersey, while

both were looking for new partners. At the time, Allen was rooming

with Mary Kelly (later to be known as Mary Livingstone), Jack

Benny’s girlfriend. Kelly introduced Allen to Burns, who had just

split with his partner Billy Lorraine. Originally interested in becom-

ing Lorraine’s partner, Allen eventually agreed to try working with

Burns. At first Allen played the straight part, but they quickly

discovered that the audience laughed at Allen much more than Burns.

‘‘I knew right away there was a feeling of something between the

audience and Gracie,’’ said Burns in a 1968 interview. ‘‘They loved

her, and so, not being a fool and wanting to smoke cigars for the rest of

my life, I gave her the jokes.’’ Working for many years as what was

known in the business as a disappointment act—an on-call position

for cancellations—they transformed a traditional ‘‘dumb Dora act’’

into something far more complicated.

After traveling around the country on the Keith-Orpheum circuit

playing onstage lovers, Allen and Burns initiated their offstage

relationship in 1925. Following a somewhat whirlwind courtship, the

pair were married on January 7, 1926. Just as their romance had

solidified into marriage, their act started to crystallize into two very

distinct characters—one frustratingly obtuse and the other patently

down-to-earth. Yet, there was an obvious intelligence behind the

pair’s verbal sparring. Burns, who wrote the majority of their materi-

al, called it ‘‘illogical logic’’—an alternative linguistic universe in

which the character of Gracie was the sole inhabitant. Their act went

on to be highlighted in such films as Fit to Be Tied (1931) and The Big

Broadcast of 1932. But, it was their variety-format radio program The

Adventures of Gracie (later known as Burns and Allen, 1932-1950)

that really won the hearts and minds of American audiences. Playing a

young boyfriend and girlfriend for the program’s first eight years,

they eventually chose to place their characters within the domestic

setting of a Beverly Hills home. This allowed them to introduce new

material and base their characters on their own lives as a middle-aged

married couple raising children in suburbia.

During their years on radio the press focused intently on their

private lives, often trying to answer the question of whether or not

Allen was as daffy as her onstage character. Articles in fan and

women’s magazines covered every detail of the entertainers’ domes-

tic life, including their friendship with fellow luminaries and neigh-

bors the Bennys, as well as their adoption of two children, Sandra and

Ronnie. Burns and Allen were exceptionally adept at using the media

attention they received to extend the narrative of their program into

the realm of ‘‘reality.’’ Not only did they purposely muddy the

distinction between their lives and that of their characters, but they

also played on-air stunts to their maximum effect. For example, in

1933, Gracie began a protracted hunt for her ‘‘missing brother,’’ a

stunt concocted by a CBS executive to raise their ratings. This

enabled her to acquire extra air by guest starring on Jack Benny’s and

Eddie Cantor’s programs under the guise of continuing her search,

and to attract attention from other media outlets. The press played

right along, photographing her looking for her brother at New York

landmarks and printing letters from fans claiming to have had

sightings of him. George Allen, Gracie’s real brother, was forced into

hiding because of the incredible attention and pressure he felt from

radio listeners and the press. In 1940 Allen topped her missing brother

gag by announcing that she would run for president. Campaigning

under the slogan ‘‘Down with common sense, vote for Gracie,’’ the

stunt, which was originally planned as a two-week, on-air gag,

snowballed. The mayor of Omaha offered to host a national ‘‘surprise

ticket party’’ convention for Allen, and the president of the Union

Pacific Railroad gave her a presidential train to travel from Los

Angeles to Omaha in a traditional ‘‘whistle stop’’ campaign.

By the time television became an option for the comedy duo in

the late 1940s, Burns and Allen were among the most well-known and

beloved comedians of their generation. Like most radio stars, they

were initially reluctant to test the new medium. So, in an effort to

avoid television’s taxing weekly production schedule and propensity

to devour material, they scheduled their live program The Burns and

Allen Show to appear only every other Thursday. Although it con-

tained many of the basic elements of their radio show, their television

program’s narrative structure and characterizations became more

nuanced. Besides the few minutes of vaudeville routine that would

end the show (including the now famous lines ‘‘Say goodnight,

Gracie!’’), Gracie and their neighbors would exist solely within the

narrative world of their sitcom. Burns, however, crossed back and

forth between the sitcom set and the edges of the stage from which it

was broadcast. Talking directly to the camera and the studio audience,

BURNS AND ALLEN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

394

Burns would comment on the plot or Gracie’s wacky antics, introduce

a song or dance act, or tell some jokes. He would then jump across the

stage and enter into the plot in progress. Burns came up with this

strategy as a way to link the show together—blending elements of the

variety format with the domestic sitcom. Burns’s technique was

incredibly effective and helped the program last through television’s

tumultuous transition in the mid-1950s from the variety show to the

sitcom, which killed off other once-popular variety programs such as

Texaco Star Theatre.

In 1958, Allen said ‘‘Goodnight, Gracie’’ for the last time. By

retiring from show business because of chronic heart problems, Allen

forced the couple’s run on television to a close. Burns tried to

continue on television playing a television producer in The George

Burns Show, but the program was canceled after only one season. He

attempted to revive his television career after Allen’s death in 1964 of

a heart attack, but almost every program he starred in was short-lived.

It wasn’t until 1975, when Burns was given the co-starring role in The

Sunshine Boys with Walter Matthau, that his career recuperated. He

went on to make a few more films (including the Oh God! films), star

in some television specials, and write several books. He never

remarried and, despite the occasional jokes of his sexual prowess,

remained in love with Gracie. Burns opened his 1988 memoir Gracie:

A Love Story by saying, ‘‘For forty years my act consisted of one joke.

And then she died.’’ Burns passed away in 1996 at the age of one

hundred, famous for his longevity and endless dedication to his wife,

his friends, and his fans.

—Sue Murray

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Gracie, as told to Jane Kesner Morris. ‘‘Gracie Allen’s Own

Story: Inside Me.’’ Woman’s Home Companion. March 1953, 122.

Blythe, Cheryl, and Susan Sackett. Say Goodnight Gracie! The Story

of Burns and Allen. New York, Dutton, 1986.

Burns, George. Gracie: A Love Story. New York, Putnam, 1988.

Burns, George, with Cynthia Hobart Lindsay. I Love Her, That’s

Why! New York, Simon and Schuster, 1955.

Burns, George, with David Fisher. All My Best Friends. New York,

Putnam, 1989.

Wilde, Larry. The Great Comedians Talk about Comedy. New York,

Citadel Press, 1968.

Burns, Ken (1953—)

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns received Oscar nominations

for two early works, Brooklyn Bridge (1981) and The Statue of

Liberty (1986). But it was his miniseries The Civil War (1990) that

brought new viewers to public television and to documentaries and

made Burns the most recognizable documentary filmmaker of all

time. The style of The Civil War merged period images with the

voices of celebrities reading the diaries and letters of Civil War

participants. Burns followed The Civil War with Baseball (1994) and

Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery (1997).

—Christian L. Pyle

Burr, Raymond (1917-1993)

Like so many actors before and after him, Raymond Burr found

one of those roles that he did so much to define, but which, at the same

time, virtually defined him. His portrayal of a lawyer in the mystery

television series Perry Mason, which ran from 1957 to 1966, and in 26

made-for-television movies, set firmly in the minds of the viewing

public what a defense lawyer should look like, how he should behave,

and how trials should transpire. Realistic or not, his success, his

interaction with clients, suspects, the police, and the district attorney,

established in people’s imaginations a kind of folk hero. For many,

‘‘Perry Mason’’ became shorthand for lawyer, as Einstein means

genius or Sherlock Holmes means detective. This compelling image

held sway for years before the profession was subjected to so much

negative scrutiny in real life and in the media. Yet, Burr, again like so

many others, did not achieve overnight fame. His role as Perry Mason

overshadowed decades of hard work in radio, the theater, and films, as

well as his business and philanthropic successes and personal tragedies.

Raymond William Stacy Burr was born on May 21, 1917 in New

Westminster, British Columbia, Canada. When he was six years old,

his parents separated, and his mother took him and his siblings to

Vallejo, California. His earliest taste of acting came in junior high

school drama classes, followed by a theatrical tour in Canada in the

summer of his twelfth year. As he grew up, he held a variety of jobs: in

the Forestry Service, and as a store manager, traveling salesman, and

teacher. He furthered his education in places as diverse as Chungking,

China, Stanford, and the University of California, where he obtained

degrees in English and Psychology. He also worked in radio, on and

off the air, wrote plays for YMCA productions, and did more

stagework in the United States, Canada, and Europe. While he was

working as a singer in a small Parisian nightclub called Le Ruban

Bleu, Burr had to return to the United States when Hitler invaded France.

In the early 1940s, he initiated a long association with the

Pasadena Playhouse, to which he returned many times to oversee and

participate in productions. After years of trying, he landed a few small

roles in several Republic Studios movies, but returned to Europe in

1942. He married actress Annette Sutherland and had a son, Michael,

in 1943. Leaving his son with his grandparents outside London while

Annette fulfilled her contract with a touring company, Burr came

back to the United States. In June 1943, Annette was killed while

flying to England to pick up Michael and join her husband in America

when her plane was shot down.

Burr remained in the United States, working in the theater,

receiving good notices for his role in Duke of Darkness, and signing a

contract with RKO Pictures in 1944. Weighing over 300 pounds, a

problem he struggled with all his life, Burr was usually given roles as

a vicious gangster or menacing villain. Late in the decade he was in

various radio programs, including Pat Novak for Hire and Dragnet

with Jack Webb. A brief marriage that ended in separation after six

months in 1948, and divorce in 1952, was followed by the tragic death

of his son from leukemia in 1953. His third wife died of cancer two

years later. Despite the misfortunes in his personal life, the roles he

was getting in radio, such as Fort Laramie in 1956, and in films,

continued to improve. By the time Perry Mason appeared, he had

been in A Place in the Sun (1951), as the district attorney, which

played a part in his getting the role of Mason, Hitchcock’s Rear

Window (1954), and the cult classic Godzilla (1954). After years of

being killed off in movies, dozens of times, according to biographer

Ona L. Hill, he was about to experience a complete role reversal.

BURRENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

395

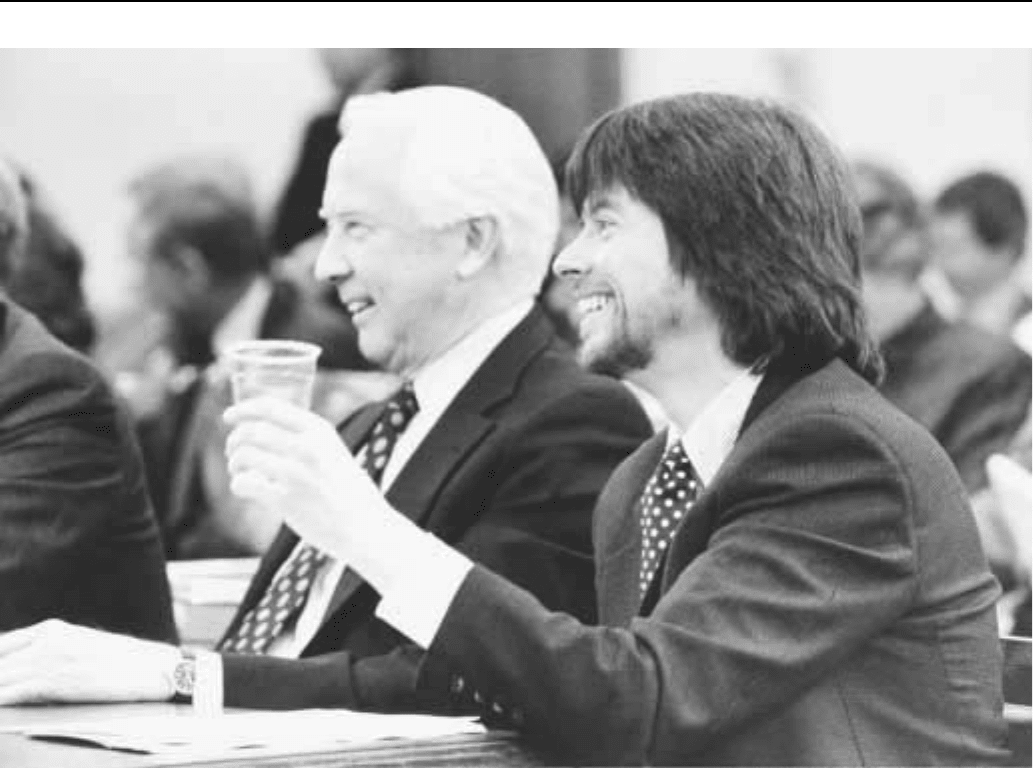

Ken Burns (right) at hearing on Capitol Hill.

The first of over eighty Perry Mason novels by Erle Stanley

Gardner had been published in 1933. Ill served, Gardner felt, by

earlier movie versions of his hero, and dissatisfied with a radio

program which ran for twelve years, he was determined to have a

strong hand in the television series. Burr auditioned for the part of the

district attorney on the condition that he be allowed to try out for the

lawyer as well. Reportedly, Gardner spotted him and declared that he

was Perry Mason. The rest of the cast, Barbara Hale as his secretary

Della Street, William Hopper as private eye Paul Drake, William

Talman as the district attorney, and Ray Collins as Lt. Tragg, melded,

with the crew, into a kind of family that Burr worked hard to maintain.

In retrospect, it is difficult to imagine the program taking any other

form: from its striking theme music to the core ensemble of actors to

the courtroom dramatics. He also gave substance to the vaguely

described character from the books, fighting unrelentingly for his

clients, doing everything from his own investigating to bending the

law and playing tricks in court to clear them and finger the guilty. In

the words of Kelleher and Merrill in the Perry Mason TV Show Book,

he was ‘‘part wizard, part snakeoil salesman.’’

One of the pieces of the formula was that Mason would never

lose a case. One of the shows in which he temporarily ‘‘lost’’

generated thousands of letters of protest. When asked about his

unblemished record, Burr told a fan, ‘‘But madam, you only see the

cases I try on Saturday.’’ Despite many ups and downs, including

hassles between Gardner and the producer and scripts of varying

quality, the show ran for 271 episodes. Though his acting received

some early criticism, Burr eventually won Best Actor Emmys in 1959

and 1961. The program was criticized for casting the prosecutor as the

villain, the police as inept, and the lawyer as a trickster, but most

lawyers, along with Burr, felt that the shows like Perry Mason

‘‘opened people’s eyes to the justice system,’’ according to Collins’

the Best of Crime and Detective TV. Burr developed an interest in law

that resulted in his speaking before many legal groups and a long

association with the McGeorge School of Law.

In March 1967, Burr reappeared on television as wheelchair-

bound policeman Ironside in a pilot that led to a series the following

September. Assembling a crime-solving team played by Don Galloway,

Barbara Anderson, and Don Mitchell, Burr, gruff and irascible, led

them until early 1975 and in 1993’s The Return of Ironside movie. In

1976-77 he starred as an investigative reporter in Kingston Confiden-

tial. Major activities in the early 1980s included a featured role in five

hours of the multipart Centennial and in Godzilla ’85. He was

associated with the Theater Department at Sonoma State University

in 1982 and some programs at California Polytechnic State Universi-

ty. In December 1985, he reprised his most famous role in Perry

Mason Returns, which led to a string of 25 more TV movies.

BURROUGHS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

396

In spite of his busy career and many personal and medical

problems, Burr still found time to become involved in various

business projects and charitable works. In 1965, he purchased an

island in Fuji, where he contributed substantially to improving living

conditions and the local economy. He also grew and sold orchids

there and in other places around the world, and had ventures in

Portugal, the Azores, and Puerto Rico. He collected art, and for

several years helped operate a number of art galleries. During the

Korean War he visited the troops twelve times, and made ten ‘‘quiet’’

trips to Vietnam, usually choosing to stop at far-flung outposts.

Though the latter were controversial, he insisted, according to Hill in

Raymond Burr: ‘‘I supported the men in Vietnam, not the war.’’

Besides financially supporting many relatives and friends over the

years, he had over 25 foster and adopted children from all over the

world, in many cases providing them with medical care and educa-

tional expenses. He was involved in numerous charitable organiza-

tions, including the Cerebral Palsy Association, B’nai B’rith, and

CARE, and created his own foundation for philanthropic, education-

al, and literary causes.

Burr was a complex man. Kelleher and Merrill describe him this

way: ‘‘Approachable to a point, yet almost regally formal. Quiet, but

occasionally preachy. Irreverent yet a student of [religions]. Intensely

serious, yet a notorious prankster . . . [and] generous to a fault.’’

Unquestionably, he worked incessantly, often to the detriment of his

health, seldom resting for long from a myriad of acting, business, and

philanthropic projects. His diligence seems to have been as much a

part of his personality as his generosity. It was in many ways

emblematic of his life and character that, despite advanced cancer, he

finished the last Perry Mason movie in the summer before he died on

September 12, 1993.

—Stephen L. Thompson

F

URTHER READING:

Bounds, J. Dennis. Perry Mason: The Authorship and Reproduction

of a Popular Hero. Westport, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Collins, Max Allan, and John Javna. The Best of Crime and Detective

TV: Perry Mason to Hill Street Blues, The Rockford Files to

Murder, She Wrote. New York, Harmony Books, 1988.

Hill, Ona L. Raymond Burr: A Film, Radio and Television Biography.

Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, Inc., 1994.

Kelleher, Brian, and Diana Merrill. Perry Mason TV Show Book. New

York, St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Riggs, Karen E. ‘‘The Case of the Mysterious Ritual: Murder Dramas

and Older Women Viewers.’’ Critical Studies in Mass Communi-

cation. Vol. 13, No. 4, 1996, 309-323.

Burroughs, Edgar Rice (1875-1950)

Perhaps best known as the creator of Tarzan the Apeman, Edgar

Rice Burroughs did much to popularize science fiction and adventure

fantasy during the first half of the twentieth century. When he turned

to writing in his mid-thirties after a mediocre and varied business life,

Burroughs met with quick success when his first publication, Under

the Moons of Mars, was serialized in All-Story magazine in 1912.

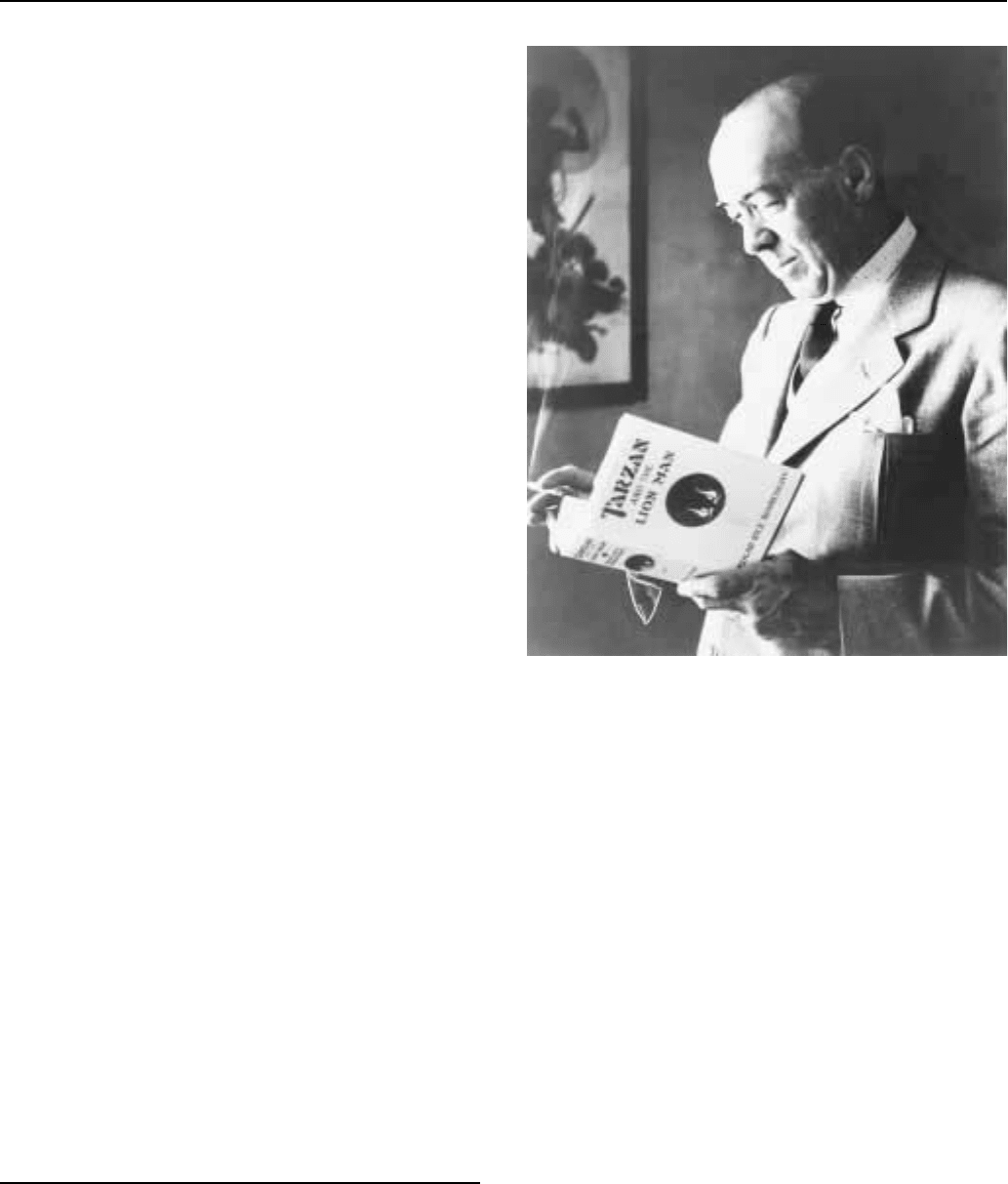

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Noted for his fertile imagination, Burroughs created several imagi-

nary societies for his popular adventure series: one set on Mars, one in

the primitive world called Pellucidar located inside the earth, and

another on Venus. His Tarzan series (started in 1918) was also set in

an imaginary Africa, much to the dismay of some readers. The

constant theme running through Burroughs’ stories was a detailing of

how alien or primitive societies inspired heroic qualities in characters.

Typically Burroughs’ stories depicted powerful men saving beautiful

women from terrible villains. Besides Tarzan, Burroughs’ most

famous character was Virginian gentleman John Carter of his Mars

series, who became the ‘‘greatest swordsman of two worlds.’’ Though

his plots were often predictable and his characters lacked depth,

Burroughs successfully captured readers’ interest in life-and-death

struggles brought on by environmental impediments. His slapdash

depictions of how primitive environments catalyze greatness in

humans have continued to entertain readers and inspire more intricate

science fiction writing.

—Sara Pendergast

F

URTHER READING:

Holtsmark, Erling B. Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston, Twayne Pub-

lishers, 1986.

Zeuschner, Robert B. Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Exhaustive Schol-

ar’s and Collector’s Descriptive Bibliography of American Peri-

odical, Hardcover, Paperback, and Reprint Editions. Jefferson,

North Carolina, McFarland, 1996.

BURROUGHSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

397

Burroughs, William S. (1914-1997)

During the 1950s, William S. Burroughs blazed many trails to

and from the elucidation of human suffering, and his obsession with

the means to this end became an enduring facet of popular culture. He

exuded the heavy aura of a misogynistic, homosexual, drug-addicted

gun nut, both in life and in print. Yet he inspired a generation of

aimless youths to lift their heads out of the sands of academe, to

question authority, to travel, and, most importantly, to intellectualize

their personal experiences.

Born William Seward Burroughs February 5, 1914 in St. Louis,

Missouri, he was the son of a wealthy family (his grandfather

invented the Burroughs adding machine) and lived a quiet mid-

Western childhood. He graduated from Harvard, but became fascinat-

ed with the criminal underworld of the 1930s and sought to emulate

the gangster lifestyle, dealing in stolen goods and eventually mor-

phine, to which he became addicted. He moved to Chicago for a time

to support his habit, then to New York City where, in 1943, he met

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg at Columbia University. He en-

couraged these younger hipster prodigies to write, and they were

impressed by his dark wit and genteel poise wizened through years of

hard living, though they rarely joined him in his escapades.

In 1947 Burroughs entered into a common law marriage to Joan

Vollmer, a Benzedrine addict whom he had also met at Columbia.

They moved to New Orleans where drugs were more easily obtain-

able, and later to Texas where they grew oranges and marijuana,

raised two children (one was Bill’s), and lived in drug-addled poverty.

On the advice of a friend, Burroughs began work on a ‘‘memory

exercise’’ which would become his first book—Junky: Confessions

of an Unredeemed Drug Addict—published in 1953 under the pseu-

donym William Lee.

Then, on September 6, 1951, while in Mexico City on the run

from the law, Bill shot and killed Joan, allegedly during their

‘‘William Tell routine.’’ After a night of heavy drinking, Bill suggest-

ed she place a glass on her head, and he would shoot at it from across

the room. ‘‘Why I did it, I do not know,’’ he later claimed. ‘‘Some-

thing took over.’’ His son went to live with his parents, but Burroughs

was never prosecuted. Instead, he embarked upon a quest to exorcize

what he called ‘‘The Ugly Spirit’’ which had compelled his lifestyle

choices and now convinced him he ‘‘had no choice but to write my

way out.’’

Burroughs fled to South America in search of the mystical drug

yage, and wrote The Yage Letters (1963) to Allen Ginsberg. Soon Bill

was back in New York City, still addicted and on the run, and

eventually ended up in The International Zone of Tangier, Morocco.

He, however, hallucinated ‘‘Interzone,’’ an allegorical city in which

‘‘Bill Lee’’ was the victim, observer, and primary instigator of

heinous crimes against all humanity. He began ‘‘reporting’’ from this

Interzone—a psychotic battleground of political, paranoid intrigue

whose denizens purveyed deceit and humiliation, controlling addicts

of sex, drugs, and power in a crumbling society spiritually malnour-

ished and bloated on excess.

When Kerouac and Ginsberg came to Tangier in 1957, they

found Burroughs coming in and out of the throes of withdrawal. He

had been sending them ‘‘reports,’’ reams of hand-written notes which

they helped to compile into Burroughs’ jarring magnum opus Naked

Lunch (1959), a work he ‘‘scarcely remembers writing.’’ This novel’s

blistering satire of post-World War II, pre-television consumer cul-

ture, and its stark presentation of tormented lost souls, were the talk of

William S. Burroughs

the burgeoning beatnik scene in the States, as were its obscene

caricatures and ‘‘routines’’ that bled from a stream of junk-

sick consciousness.

Burroughs was soon regarded as the Godfather of the Beat

Generation, a demographic that came of age during World War II

while Bill was out looking for dope, and which aimed to plumb the

depths of existence in post-modern America. Mainstream appeal

would prove elusive to these writers, though, until Naked Lunch

became the focus of a censorship trial in 1965. The proceedings drew

attention—and testimony—from such literati as Norman Mailer,

John Ciardi, and Allen Ginsberg, whose reputation had grown as well.

After the furor died down, Naked Lunch remained largely an under-

ground hit. Burroughs also stayed out of sight, though he published

The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and

Nova Express (1964) using an editing technique with which he had

been experimenting in Tangier and called ‘‘cut-ups’’: the random

physical manipulation of preconceived words and phrases into

coherent juxtapositions.

In the 1970s, Burroughs holed up in his New York City ‘‘bunk-

er’’ as his writing became the subtext for his gnarled old junky image.

Though he had been an inspiration to authors, he found himself

rubbing elbows with post-literate celebrity artistes yearning for the

Ugly Spirit. Later, Burroughs enjoyed a spate of speaking tours and

BUSTER BROWN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

398

cameos in films. He also published books revisiting the themes of his

early routines, and in 1983 was inducted into the American Academy

and Institute of Arts and Letters. He later recorded and performed

with John Giorno Poetry Systems, Laurie Anderson, Material, the

Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, and Kurt Cobain of Nirvana,

among others. In the 1990s his face and silhouette, as well as his

unmistakable thin, rattling voice quoting himself out of context, were

used to promote everything from running shoes to personal comput-

ers. He spent most of his last years in seclusion in Lawrence, Kansas,

where he died August 2, 1997.

Burroughs’ influence on popular culture is evident in every

medium, though he is more often referred to than read. From

subversive comedic diatribes on oppressive government to the gritty

realism of crime drama, from the drug chic youth culture enjoys (and

has enjoyed since the early 1960s) to paranoia over past, present, and

future drug wars, Burroughs made hip, literate cynicism both popular

and culpable.

—Tony Brewer

F

URTHER READING:

Caveney, Graham. Gentleman Junkie: The Life and Legacy of Wil-

liam S. Burroughs. Canada, Little Brown, 1998

Miles, Barry. William Burroughs: El Hombrè Invisible: A Portrait.

New York, Hyperion, 1993.

Morgan, Ted. Literary Outlaw: A Life of William S. Burroughs. New

York, Holt, 1988.

Buster Brown

Buster Brown first appeared in the New York Herald on May 4,

1902. Accompanied by his dog Tige, Buster Brown was a mischie-

vous young boy given to playing practical jokes. He resolved weekly

to improve his ways, but always strayed. The strip was the second

major success for Richard Outcault (1863-1928) who had earlier

created the Yellow Kid. Outcault licensed the image and the name of

his character to a wide variety of manufactures and the name Buster

Brown is probably more familiar to Americans as a brand of shoes or

children’s clothing than as the title of a comic strip. Unlike Outcault’s

early work Buster Brown was distinctly a comic strip appearing

weekly in twelve panel full page stories. Once again William Ran-

dolph Hearst lured Outcault to his newspapers and Buster Brown

commencing there January 21, 1906. The resulting court cases over

copyright determined that Outcault owned all subsidiary rights to the

Buster Brown name having purchased them for $2 when he signed

with the Herald to produce the strip. Outcault derived considerable

income from his licensing efforts and his advertising agency, which

produced over 10,000 advertisements for Buster Brown related

products. The last original episode of the strip was published Decem-

ber 11, 1921.

—Ian Gordon

F

URTHER READING:

Gordon, Ian. Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890-1945. Wash-

ington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

This 1969 film, the first deconstructionist Western, set the tone

for future buddy comedies, helped revive the Western film genre, and

made a superstar out of Robert Redford, whose Sundance Institute has

become the major supporter of independent films. Also starring Paul

Newman as Butch and Katherine Ross as Etta Place, and directed by

George Roy Hill, this lighthearted, ‘‘contemporary’’ Western paved

the way for modern Westerns such as Young Guns and The Long Riders.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was based on the lives of

two actual Old West outlaws—Robert Leroy Parker (Butch) and

Harry Longabaugh (Sundance). By the 1890s, Butch was the head of

the largest and most successful outlaw gang in the West, known as

both the Wild Bunch and the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. Butch was

chosen leader based solely on his personality; he was a poor shot who

never killed anyone until later in life. Sundance, who got his nick-

name from spending eighteen months in jail in Sundance, Wyoming,

was a gang member and a phenomenal gunman who, incidentally, did

not know how to swim (a fact yielding the film’s best joke). Based at

their hideout at Hole-in-the-Wall near Kaycee, Wyoming, the gang

members robbed banks and trains throughout the West. When the

railroads hired the Pinkerton Agency to catch the gang and the agency

formed a relentless superposse, Butch, Sundance, and female com-

panion Etta Place moved to South America and bought a ranch in

Argentina. They tried to make an honest living but eventually began

robbing banks in several South American countries. It is believed they

were killed after being trapped by troops in Bolivia—although some

maintain that Butch and Sundance spread the story after another pair

of outlaws was gunned down by Bolivian troops.

Screenwriter William Goldman first came across the Butch

Cassidy story in the late 1950s, and he researched it on and off for the

next eight years. An established novelist, Goldman decided to turn the

story into a screenplay for the simple reason ‘‘I don’t like horses.’’ He

didn’t like anything dealing with the realities of the Old West. A

screenplay would be simpler to write and wouldn’t involve all the

research necessary to write a believable Western novel. From the

outset, this screenplay established itself as more contemporary than

the typical Western or buddy film. In the film, Butch and Sundance do

what typical Western movie heroes never do, such as run away

halfway through the story or kick a rival gang member in the groin

rather than fight with knives or guns. While there had been buddy

films in the past, including those starring Abbott and Costello, and

Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, those films were joke factories, varia-

tions on old vaudeville routines. Part of the challenge for Goldman

was to write dialogue that was funny without being too funny;

nonstop jokes abruptly interrupted by a hail of gunfire would be too

great a transition to expect an audience to make. Goldman found the

right tone, a kind of glib professionalism emphasizing chemistry over

jokes, and it is the chemistry between Newman and Redford that

made the film such a success.

This glib professional tone since has been put to good use in a

number of other films and television shows, as in the 48 Hours and

Lethal Weapon films. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid also led to

the sequel, Wanted: The Sundance Woman, and the prequel, Butch

and Sundance—The Early Years; and Newman and Redford success-

fully teamed up again for The Sting (1973).

—Bob Sullivan