Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BUCKLEYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

379

Morrow, and syndicated by the New York Times. None of these latter

ventures was particularly successful, and more recent attempts to

revive Buck Rogers have been even less so.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Dille, Robert C., editor. The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the

25th Century. New York, Chelsea House, 1969.

Goulart, Ron. The Adventurous Decade. New Rochelle, Arlington

House, 1975.

Sheridan, Martin. Comics and Their Creators. Boston, Hale, Cush-

man and Flint, 1942.

Buckley, William F., Jr. (1925—)

William F. Buckley Jr. found fame as the voice of conservatism.

Founder of the National Review, the conservative journal of opinion

of which he was editor-in-chief until 1990, Buckley also worked as an

influential political advisor and popular novelist. Buckley aptly

described the effect of his National Review through his character

Boris Bolgin in his spy novel Who’s on First. ‘‘‘Do you ever read the

National Review, Jozsef?’, asks Boris Bolgin, the chief of KGB

counter intelligence for Western Europe, ‘It is edited by this young

bourgeois fanatic. Oh, how they cried about the repression of the

counter-revolutionaries in Budapest! But the National Review it is

also angry with the CIA for—I don’t know; not starting up a Third

World War, maybe? Last week—I always read the National Review,

it makes me so funny mad—last week an editorial said’—he raised his

head and appeared to quote from memory—‘The attempted assassi-

nation of Sukarno last week had all the earmarks of a CIA operation.

Everybody in the room was killed except Sukarno.’’’

William Frank Buckley, Jr. was born in New York City in 1925

into a wealthy Connecticut family of Irish decent. He grew up in a

devout Christian Catholic atmosphere surrounded by nine brothers

and sisters. He attended Millbrook Academy in New York and then

served as a second lieutenant in World War II. After his discharge in

1946 he went to Yale bringing with him, as he wrote, ‘‘a firm belief in

Christianity and a profound respect for American institutions and

traditions, including free enterprise and limited government.’’ He

found out that Yale believed otherwise. After graduating with honors

in 1950, he published the public challenge to his alma mater God and

Man at Yale in 1951. It brought him instant fame. He claimed that

Yale’s ‘‘thoroughly collectivist’’ economics and condescending views

towards religion could only lead towards a dangerous relativism, a

pragmatic liberalism without a moral heart. What America required

and conservatism must supply was a fighting faith, noted David

Hoeveler in Watch on the Right, and William ‘Bill’ Buckley, Jr. was

just the man for the job.

In 1955 he founded the National Review, creating one of the

most influential political journals in the country. His syndicated

column, On the Right, which he started to write in 1962, has made its

weekly appearance in more than 300 newspapers. Not only in print

has he been America’s prime conservative voice, Buckley also hosts

the Emmy award-winning show Firing Line—Public Broadcasting

Service’s longest-running show—which he started in 1966. The

Young Americans for Freedom Movement (1960) which aimed at

conservative control of the Republican Party was Buckley’s brain-

child. He has written and edited over 40 books which include political

analyses, sailing books and the Blackford Oakes spy novels and has

been awarded more than 35 honorary degrees. In 1991 he received the

Presidential Medal of Freedom. As a member of the secretive

Bilderberg Group and the Council on Foreign Relations—founded in

1921 as an advisory group to the President—he also plays an

important political advisory role. His spy novels, however, show most

clearly how much he perceived the Cold War to be essentially a

spiritual struggle.

Remarking to his editor at Doubleday, Samuel Vaughan, that he

wanted to write something like ‘Forsyth,’ Vaughan expected a

Buckley family saga in Galsworthy’s Forsythe Saga tradition. But

Buckley was referring to Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal

and produced Saving the Queen, which made the best-seller lists a

week before its official publication date. After watching the anti-CIA

movie Three Days of the Condor, Buckley—who himself worked

briefly (nine months) as a CIA covert agent—set out to write a book in

which ‘‘the good guys and the bad guys were actually distinguish-

able.’’ That history is the ‘‘final’’ fiction is one of the themes of his

Blackford Oakes novels that always take as their starting point an

historical ‘‘fact.’’ But his main interest lay in countering the charges

that there was no moral difference between Western intelligence and

its Soviet counterpart. In his Craft of Intelligence, former CIA

Director Allen Dulles, who figures frequently in Buckley’s novels,

claimed that ‘‘Our intelligence has a major share of the task of

neutralizing hostile activities. Our side chooses the objective. The

opponent has set up the obstacles.’’ Buckley frames it differently in

his novel Stained Glass: ‘‘Our organization is defensive in nature. Its

aim is to defeat your aggressive intentions. You begin by the

dissimilarities between Churchill and Hitler. That factor wrecks all

derivative analogies.’’

Buckley’s conservatism is deeply spiritual but never orthodox.

In a direct contradiction of conservative and Republican politics, he

claimed in a 1996 cover story of the National Review ‘‘The War on

Drugs Is Lost,’’ that ‘‘the cost of the drug war is many times more

painful, in all its manifestations, than would be the licensing of drugs

combined with an intensive education of non-users and intensive

education designed to warn those who experiment with drugs.’’ In his

syndicated column he wrote of his sister’s cancer chemotherapy and

her need for medical marijuana. Buckley’s public stand and personal

drama are closely related. In Watch on the Right, David Hoeveler sees

this communal and familial conservative pathos as a defining quality

of Buckley’s character: ‘‘The conservative movement for Buckley

was a family affair, it flourished with friendships within and struck

forcefully at the enemy without.’’ Nine of the ten Buckley children at

one time contributed to the National Review.

Being Catholic always mattered more to him than being conser-

vative, Gary Willis noted in his Confessions of a Conservative. When

asked in an Online Newshour interview about his book Nearer, My

God: An Autobiography of Faith, how his Christian belief influenced

his views on conservatism, he laughed his reply: ‘‘Well, it’s made me

right all the time.’’

—Rob van Kranenburg

F

URTHER READING:

Buckley, William F., Jr. God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of

Academic Freedom. Chicago, Regnery, 1951.

BUCKWHEAT ZYDECO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

380

———. Nearer, My God: An Autobiography of Faith. New York,

Doubleday, 1997.

———. Saving The Queen. New York, Doubleday, 1976.

———. Stained Glass. New York, Doubleday, 1978.

———. Who’s on First. New York, Doubleday, 1980.

Dulles, Allen. The Craft of Intelligence. New York, Harper and

Row, 1963.

Hoeveler. J. David, Jr. Watch on the Right: Conservative Intellectuals

in the Reagan Era. Madison, The University of Wisconsin

Press, 1991.

Willis, Gary. Confessions of a Conservative. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1979.

Buckwheat Zydeco (1947—)

Stanley ‘‘Buckwheat’’ Dural, Jr. is one of the premier perform-

ers and representatives of the black Creole dance music of southwest

Louisiana known as zydeco. In 1979, after playing for nearly three

years in Clifton Chenier’s band, he added Zydeco to his nickname and

formed the Ils Sont Partis Band, which takes its title from the

announcer’s call at the start of each horse race at Lafayette’s Evangeline

Downs, in the heart of French-speaking Louisiana. An accomplished

accordionist, Buckwheat has perhaps done more than anyone else to

popularize zydeco and increase its appeal within a wider popular

culture. He played for President Clinton’s inaugural parties and for

the closing ceremonies of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. His

tunes now find their way on to television commercials and movie

soundtracks, but even multiple Grammy Award nominations have not

diminished his allegiance to what he calls his ‘‘roots music.’’

—Robert Kuhlken

F

URTHER READING:

Nyhan, Patricia, Brian Rollins, David Babb, and Michael Doucet. Let

the Good Times Roll! A Guide to Cajun & Zydeco Music. Portland,

Maine, Upbeat Books, 1997.

Tisserand, Michael. The Kingdom of Zydeco. New York, Arcade

Publishing, 1998.

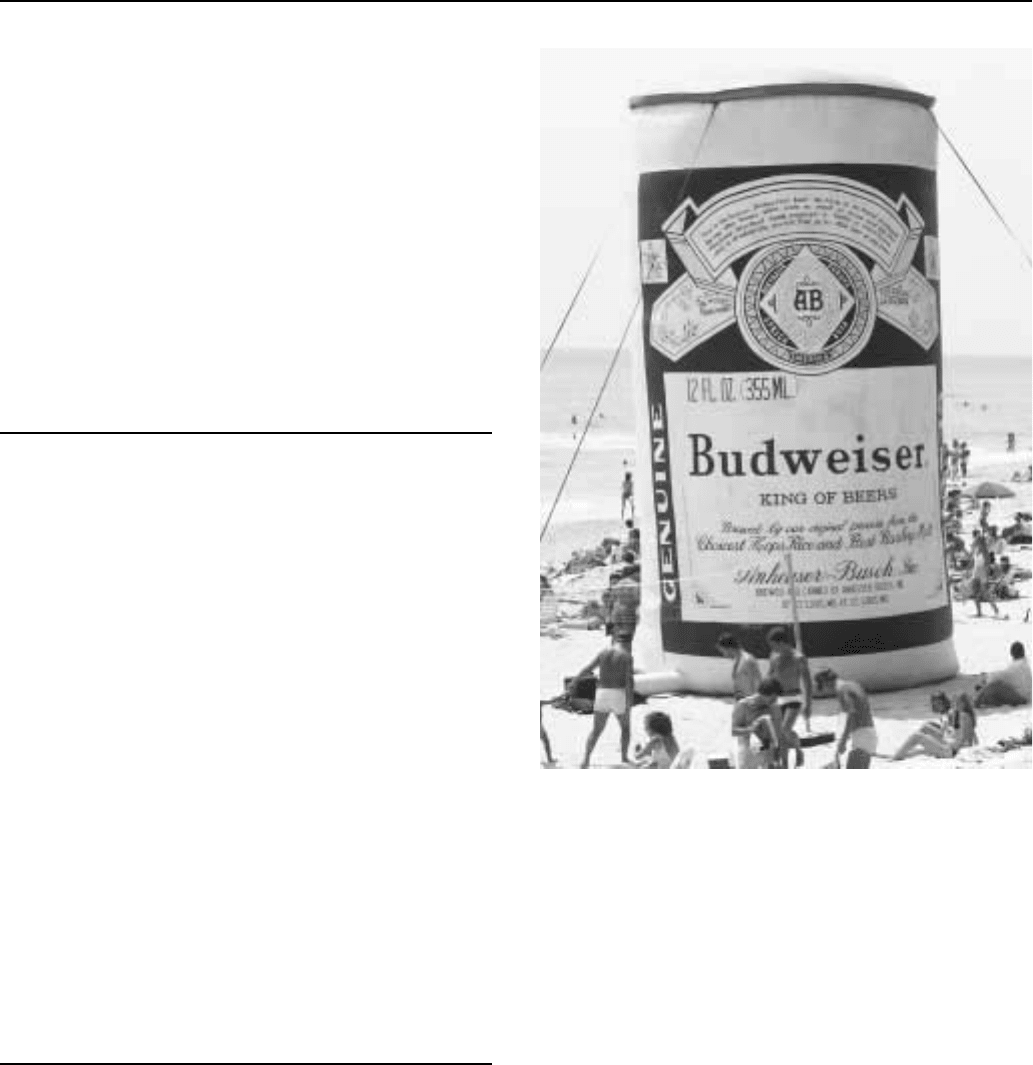

Budweiser

Along with Coca-Cola, Budweiser beer is America’s drink. One

out of five alcoholic drinks sold in America is a Bud, and, now that the

King of Beers is being sold in more than 60 countries worldwide,

Budweiser is the world’s most popular beer. This lightly-hopped,

smooth lager has a long history in the United States, but it was

beginning in the 1970s that Budweiser became a true icon of

American culture, thanks to a model of commercial development that

is the envy of the world. Faced with increasing competition from the

Miller Brewing Company, Budweiser parent Anheuser-Busch began

putting the Budweiser name everywhere: on coolers, blimps, and

boxer shorts; on football games, car races, and other sports. The

company’s carefully crafted advertising campaigns were equally

ubiquitous: ‘‘This Bud’s for you’’; ‘‘Budweiser . . . The King of

A large, inflatable Budweiser beer can on Cocoa beach in Florida.

Beers’’; the Bud Bowl; the Budweiser frogs and lizards; and, of

course, the Budweiser Clydesdales all kept the Budweiser brands

alive in the consumers’ mind. The brewery bought the St. Louis

Cardinals baseball team and opened theme parks in Florida and

Virginia; these were family entertainments, but the ties to the beer

brands were always evident. Such marketing tactics were backed by

the most efficient beer production and distribution systems in the world.

The Anheuser-Busch brewing company traced its history back to

St. Louis breweries in the mid-1800s. In 1865, the brewery produced

8,000 barrels; these numbers grew quickly when Budweiser Lager

Beer was introduced in 1876. The brewing company expanded

horizontally, purchasing bottlers and glass companies. Soon it con-

trolled all the means for producing its beer and in 1901 Anheuser-

Busch was well on its way to being America’s brewery, breaking the

million-barrel mark for the first time with 1,006,494 barrels. With the

nation under the grips of National Prohibition in 1920, the brewery

unveiled Budweiser near-beer (selling 5 million cases) and began

manufacturing ice cream. With the retraction of Prohibition in 1933

the company introduced the Budweiser Clydesdales, which have

remained an icon of the company’s commitment to tradition. In the

1950s, the company implemented plans to open Busch drinking

gardens in various cities, in an attempt to tap into a European

tradition. In addition, advertising gimmicks became a significant part

BUFFALO SPRINGFIELDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

381

of Bud’s appeal. From the Clydesdales of the 1930s, advertisers

welcomed ‘‘Bud Man’’ in 1969, a campaign which sought to tie the

beer to gender roles and expectations of masculinity. Today, Budweiser

still uses the saying ‘‘This Bud’s for you,’’ but it most often aims

toward a broader, un-gendered public with advertising gimmicks

such as the ‘‘Bud Bowl’’ and talking frogs. Budweiser was also one of

the first beers to incorporate requests for responsible-drinking in its

advertisements in the late 1980s.

In 1980 Budweiser made history by expanding into the global

marketplace with agreements to brew and sell in Canada, Japan, and

elsewhere. This corporate development fueled Anheuser-Busch’s

staggering rise in production, which exceeded 100 million barrels per

year in the late 1990s and gave the company nearly half of all beer

sales worldwide and around 40 percent of beer sales in the United

States. Budweiser—along with the brand extensions Bud Light, Bud

Dry, and Bud Ice—is thus poised to become to the rest of the world

what it already is to the United States: a mass-produced, drinkable

beer that symbolizes the ‘‘good life’’ made possible by corporate

capitalist enterprise. Beer purists and fans of locally-produced

microbrews may decry the bland flavor and lack of body of the

world’s best-selling beer, but millions of beer drinkers continue to put

their money down on the bar and ask for a Bud.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Budweiser.com.’’ http://www.budweiser.com. April 1999.

Hernon, Peter, and Terry Ganey. Under the Influence: The Unauthor-

ized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1991.

Plavchan, Ronald Jan. A History of Anheuser-Busch, 1852-1933.

New York, Arno Press, 1976.

Price, Steven D. All the King’s Horses: The Story of the Budweiser

Clydesdales. New York, Viking Penguin, 1983.

Rhodes, Christine P., editor. The Encyclopedia of Beer. New York,

Henry Holt & Co., 1997.

Yenne, Bill. Beers of North America. New York, Gallery Books, 1986.

Buffalo Springfield

Despite releasing three accomplished albums which were inno-

vative and influential exemplars of the ‘‘West Coast sound’’ of the

mid- to late 1960s, Buffalo Springfield only had a limited impact on

the public consciousness during its brief and tempestuous heyday.

However, the continued cultural resonance of their solitary hit single,

‘‘For What It’s Worth,’’ combined with the subsequent critical

acclaim and commercial success of its alumni, has ensured Buffalo

Springfield of a somewhat mythical status in popular music history.

The genesis of Buffalo Springfield proceeded slowly through

various musical styles and right across the North American continent.

Stephen Stills and Richie Furay met in folk music mecca Greenwich

Village, and first played together in an eccentric nine-man vocal

ensemble called the Au Go Go singers, which released an obscure

album in 1964. Fellow singer-songwriter Neil Young encountered

Stills in Ontario, and Furay in New York, before befriending bassist

Bruce Palmer on the Toronto coffee-house music scene. Young and

Palmer joined a blues-rock group, The Mynah Birds, which was

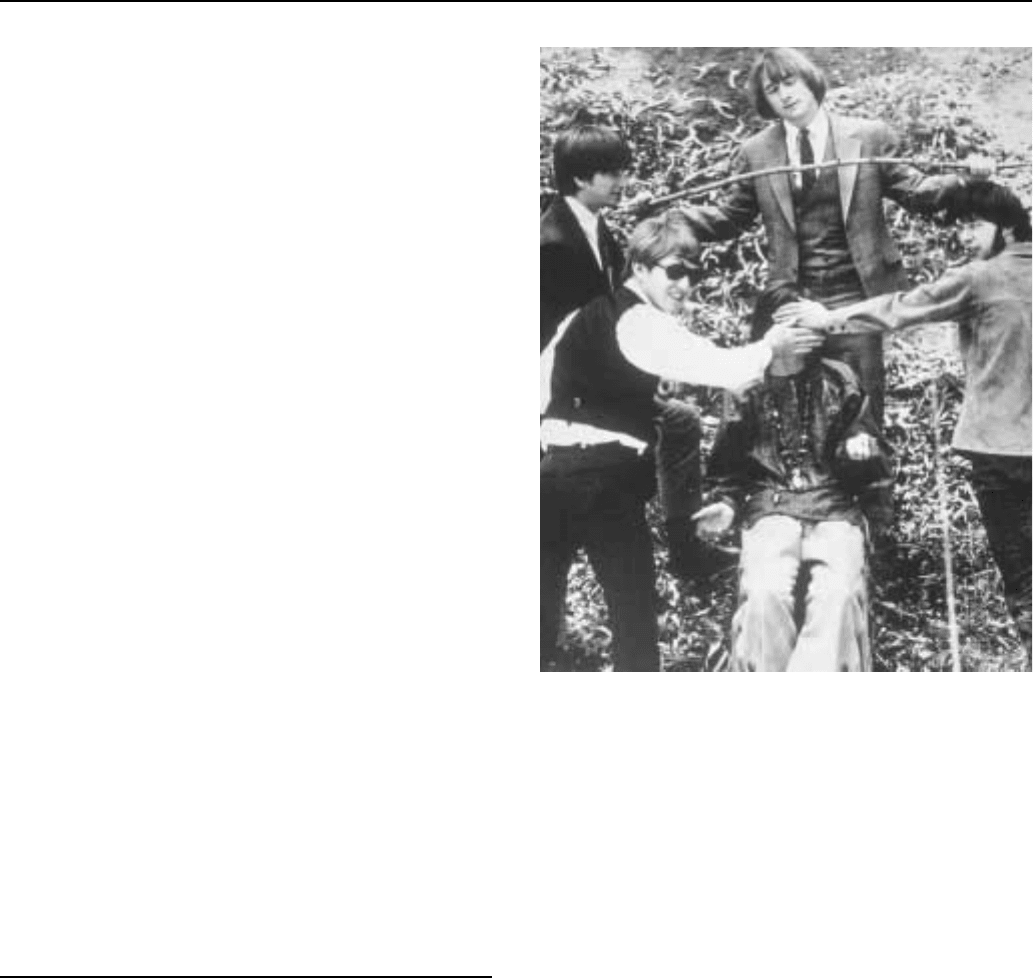

Members of the group Buffalo Springfield c. 1967, featuring Stephen

Stills (top) and Neil Young (right).

briefly signed to Motown in 1965. The four young musicians finally

came together as a group when Stills and Furay spotted the two

Canadians in a Los Angeles traffic jam in early 1966. Supplemented

by another Canadian, experienced session drummer Dewey Martin,

the fledgling Buffalo Springfield were, in the words of Johnny Rogan,

‘‘potentially the most eclectic unit to appear on the West Coast scene

since the formation of the Byrds.’’

Byrds’ bassist Chris Hillman arranged for Buffalo Springfield to

play at the prestigious Los Angeles club Whisky A Go Go, and the

gigs immediately attracted such local luminaries as David Crosby, the

Mamas and Papas, and Sonny and Cher. Furay, Stills and Young

would later assert that Buffalo Springfield peaked during these early

live appearances, and that by comparison, in Young’s words, ‘‘All the

records were great failures.’’ The band released the first of those

records in July 1966, Young’s precocious ‘‘Nowadays Clancy Can’t

Even Sing’’ backed with Stills’ ‘‘Go and Say Goodbye.’’ The single

was not a commercial success, but it provides a suitable example of

the contrast at this time between Stills’ stylish but typical ‘‘teenybop’’

narratives of young love, and Young’s more lyrically obtuse reper-

toire. As Stills later noted, ‘‘He [Young] wanted to be Bob Dylan and

I wanted to be The Beatles.’’

Buffalo Springfield’s eponymous debut album was released in

February 1967. The lyrics to Young’s ‘‘Burned,’’ ‘‘Out of My Mind’’

and ‘‘Flying on the Ground Is Wrong’’ all alluded to the effects of

fashionable psychedelic drugs. Buffalo Springfield achieved com-

mercial success with their next single, ‘‘For What It’s Worth,’’ which

reached number 7 on the national chart. An artistic leap for Stills, the

BUFFETT ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

382

song was a coolly sardonic study of the violent action of police against

hippy protesters on Sunset Strip in late 1966. Though ‘‘For What It’s

Worth’’ captured the significance of the conflict between the authori-

ties and the emerging ‘‘counterculture,’’ the single’s sales were

concentrated in California, suggesting that middle America had little

empathy with such provocative lines as ‘‘What a field day for the heat

[police]/A thousand people in the street.’’

By early 1967, Buffalo Springfield was riven with problems.

Palmer had been charged with possession of drugs and deported back

to Canada, and Young began to work with former Phil Spector

associate Jack Nietzsche. The group played an acclaimed concert

with Palmer and without Young at the Monterey Pop Festival in June

1967. Renegade Byrd David Crosby substituted for Young at this

legendary zenith of the hippy era. Young returned to Buffalo Spring-

field in September 1967 and the band released their second long-

player. Though Rolling Stone pertinently observed that ‘‘This album

sounds as if every member of the group is satisfying his own musical

needs,’’ the diverse and ambitious Buffalo Springfield Again is an

acknowledged classic. The album included Young’s impressionistic

six-minute collage ‘‘Broken Arrow,’’ Stills’ guitar and banjo epic

‘‘Bluebird,’’ and ‘‘Rock ’n’ Roll Woman,’’ an ode to Jefferson

Airplane singer Grace Slick co-written by Stills and Crosby.

Buffalo Springfield unravelled in early 1968: Palmer was busted

and deported again in January, and in March, Young, Furay and the

latest bassist, Jim Messina, were arrested on a drugs charge with

Cream member Eric Clapton. When Buffalo Springfield finally

disbanded in May, Rolling Stone cited ‘‘internal hassle, extreme

fatigue coupled with absence of national success and run-ins with the

fuzz.’’ The hippy argot rather disguised the extent to which the

internecine egotism of Stills and Young, even more than the drug

busts, had dissolved Buffalo Springfield. It was left to Furay and

Messina to organise tracks recorded at the end of 1967 for the

inevitably inconsistent Last Time Around, released in August 1968

after Buffalo Springfield had disbanded.

Stills joined Crosby in the prototypical ‘‘supergroup’’ Crosby,

Stills and Nash; Young became a significant solo artist and occasion-

ally augmented CSN; and Furay and Messina formed the country-

rock outfit Poco. A reunion of the original members occurred in 1982,

but it never advanced beyond rehearsals. Despite being inducted into

the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1997, Buffalo Springfield remains

disproportionately represented in popular culture by ‘‘For What It’s

Worth,’’ a standard of the soundtracks to many documentaries and

movies (Good Morning Vietnam, Forrest Gump) about the cultural

conflicts of the 1960s. In 1998, the song was more imaginatively

utilised by rap group Public Enemy in the title song for the film He

Got Game. Stills’ famous riff and lyrics were combined with the

rhymes of Public Enemy’s frontman, Chuck D, in an inspired meeting

of two radically different forms and eras of political popular music.

—Martyn Bone

F

URTHER READING:

Einarson, John, with Richie Furay. For What It’s Worth: The Story of

Buffalo Springfield. Toronto, Quarry Press, 1997.

Jenkins, Alan, editor. Neil Young and Broken Arrow: On a Journey

Through the Past. Bridgend, Neil Young Appreciation Socie-

ty, 1994.

Rogan, Johnny. Neil Young: The Definitive Story of His Musical

Career. London, Proteus, 1982.

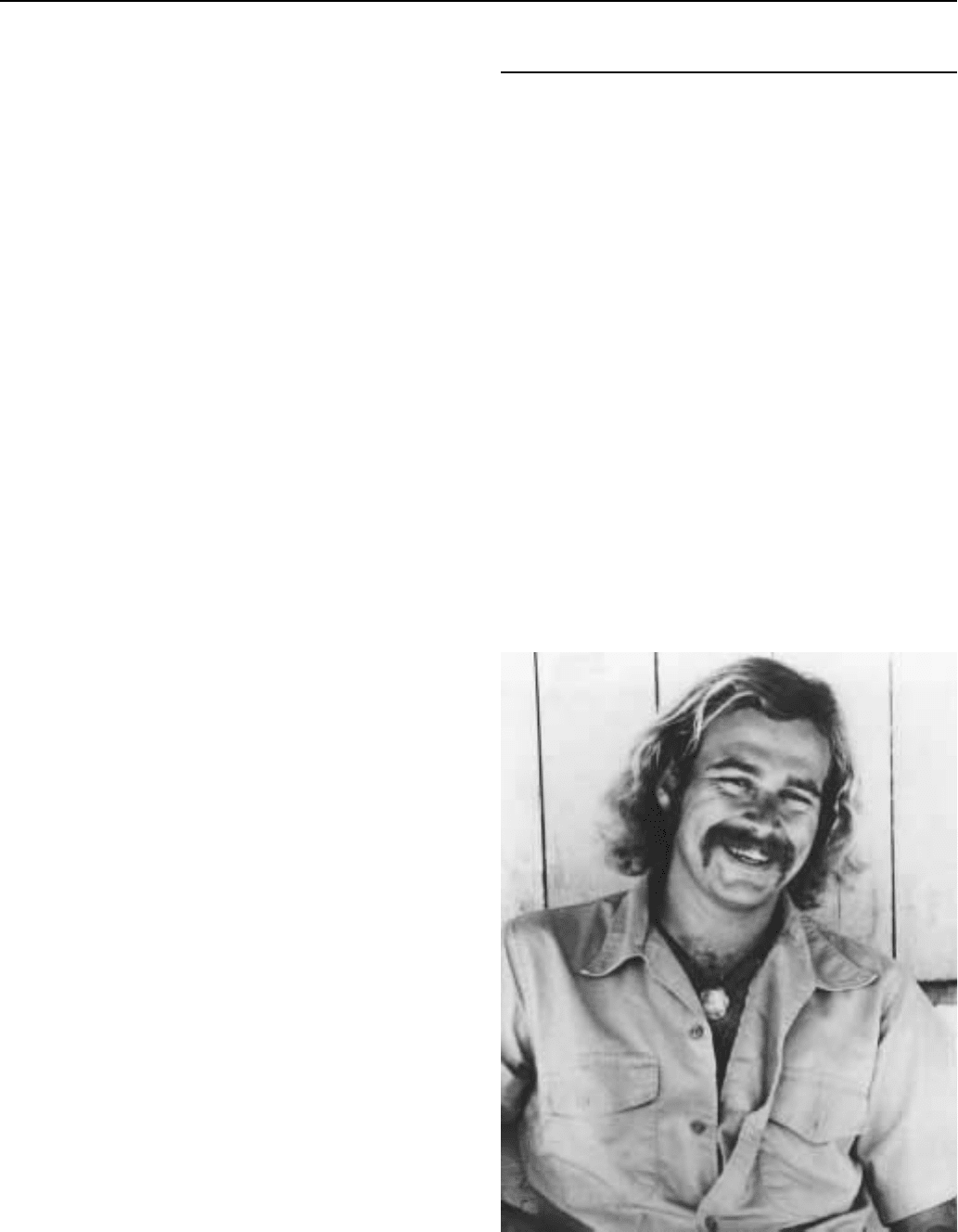

Buffett, Jimmy (1946—)

Devoted fans—affectionately dubbed Parrot Heads—find es-

capism in Jimmy Buffett’s ballads, vicariously experiencing through

his strongly autobiographical songs Buffett’s life of beaches, bars,

and boats. Yet Buffett’s life has been far more than rum-soaked nights

and afternoon naps in beachside hammocks. Even though Buffett

relishes his image of ‘‘the professional misfit,’’ this millionaire

‘‘beach bum’’ is actually an ambitious and clever entrepreneur.

Born on Christmas Day, 1946 in Pascagoula, Mississippi, Jim-

my Buffett spent most of his youth in the Catholic school system in

Mobile, Alabama. During college he learned to play the guitar and

started singing in clubs. While attending the University of Southern

Mississippi, about 80 miles from New Orleans, Buffett played

regularly at the Bayou Room on Bourbon Street. Once he had a taste

of performing, his life course was set. Even though he married and

took a job at the Mobile shipyards after college, Buffett continued to

spend his nights playing at hotel cocktail lounges.

Lacking the money to move to Los Angeles, where Jimmy had a

job offer at a club, the Buffetts moved instead to Nashville. Buffett

made a living by writing for Billboard magazine, but he also contin-

ued to write new songs. The first of these songs to get recorded was

‘‘The Christian?’’ on Columbia Records’ Barnaby Label. In 1970,

Buffett recorded an album, Down to Earth, for the Barnaby label.

Sales were so disappointing that Barnaby did not release Buffett’s

next album, High Cumberland Jubilee, recorded in 1971, until 1977.

Buffett hired a band and toured in an attempt to promote his first

Jimmy Buffett

BUGS BUNNYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

383

album, but within a few months he ran out of money. Career

frustrations took a toll on his marriage.

In his mid-twenties, Buffett found himself broke, divorced, and

hating Nashville. Then in 1971, Jimmy Buffett took a trip that

changed his life and his music. Fellow struggling singer Jerry Jeff

Walker invited Buffett down to his home in Summerland Key, just 25

miles from Key West. It was the beginning of Key West’s ‘‘decade of

decadence,’’ and Buffett quickly immersed himself in the Conch

subculture’s nonstop party that they referred to as the ‘‘full-tilt

boogie.’’ To maintain the freedom of his new lifestyle Buffett ran up

bar tabs, literally played for his supper, and got involved in the local

cottage industry—drug smuggling.

The lifestyle and the local characters became the substance of

Buffett’s songs. The first of the Key West-inspired songs appeared in

1973 when he landed a record deal with ABC/Dunhill and recorded A

White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean. The tongue-in-cheek ‘‘The

Great Filling Station Holdup’’ made it to number 58 on Billboard’s

country charts. The most infamous song from the album, ‘‘Why Don’t

We Get Drunk (and Screw),’’ became a popular jukebox selection

and the favorite Buffett concert sing-along song.

ABC’s rising star, Jim Croce, died in 1973, and the record

company looked to Jimmy Buffett to fill his shoes. They even

promoted Buffett’s next album, 1974’s Living and Dying in 3/4 Time,

with a fifteen-minute promotional film that showed in ABC-owned

theaters. ‘‘Come Monday’’ made it all the way to number 30 on the

billboard pop charts. For years, Buffett had been making reference to,

even introducing, his mythical Coral Reefer Band. In the summer of

1975 he put together an actual Coral Reefer Band to tour and promote

his third ABC/Dunhill album, A1A. The album contains ‘‘A Pirate

Looks at Forty,’’ which became a central tale in the mythos Buffett

was spinning, and a virtual theme song for every Buffett fan as they

neared middle age. 1976’s Havana Daydreamin’ got good reviews

and fed the frenzy of his growing cult following; but it was 1977’s

Changes in Latitude, Changes in Attitude that was the defining

moment of his career. The album’s hit single, ‘‘Margaritaville,’’

stayed in the Billboard Top 40 charts for fifteen weeks, peaking at

number eight. That summer ‘‘Margaritaville’’ permeated the radio

and Buffett opened for the Eagles tour. The exposure helped Changes

in Latitude, Changes in Attitude go platinum.

The song ‘‘Margaritaville’’ gave a name to the place fans

escaped when they listened to Jimmy Buffett’s music. And

Margaritaville was wherever Jimmy Buffett was playing his music,

be that Key West, Atlanta, or Cincinnati. Supposedly it was at a

concert in Cincinnati in the early 1980s that Eagles bassist Timothy B.

Schmidt looked out at the fans in wild Hawaiian shirts and shark fin

hats and dubbed them Parrot Heads. By the late 1980s the Parrot Head

subculture had grown to the point that Buffett had become one of the

top summer concert draws. The concerts were giant parties with

colorful costumes, plentiful beer, and almost everyone singing along

out of key with the songs they knew by heart. The concerts were more

about the experience than about hearing Jimmy Buffett sing.

Buffett soon found ways to extend the experience beyond the

concerts. Although he continued to average an album a year, he also

began to develop diverse outlets for his creativity, and aggressively

marketed the Margaritaville mythos. The Caribbean Soul line of

clothing appeared in 1984, and in 1985 he opened Jimmy Buffett’s

Margaritaville store in Key West. A few months after opening the

store, he sent out a 650 copy initial mailing of Coconut Telegraph, a

combination fan newsletter and advertising flyer for Buffett parapher-

nalia. It was in the April 1985 issue that the term Parrot Head was first

officially used to refer to Buffett’s fans. By the end of the decade, the

newsletter had 20,000 subscribers.

Buffet reasoned that anyone who wanted to read his newsletter

would buy a book with his name on it. His first literary effort, in 1988,

was Jolly Mon, a children’s book he co-wrote with his daughter

Savannah Jane. The following year, Buffett’s collection of short

stories, Tales from Margaritaville, became a bestseller. His first

novel, Where is Joe Merchant?, warranted a six figure advance and

became a bestseller in 1992. By this time Buffett had opened a

Margaritaville cafe next to the store in Key West. Eventually, he

opened Margaritaville clubs and gift shops in New Orleans, Charles-

ton, and Universal Studios in Florida.

More than anything else, Jimmy Buffett is a lifestyle artist.

Whether it be a Caribbean meal, a brightly colored shirt, a CD, or a

live performance, Buffett transports his fans to the state of mind that

is Margaritaville.

—Randy Duncan

F

URTHER READING:

Eng, Steve. Jimmy Buffett: The Man from Margaritaville Revealed.

New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Humphrey, Mark, and Harris Lewine. The Jimmy Buffett Scrapbook.

New York, Citadel Press, 1995.

Ryan, Thomas. The Parrot Head Companion: An Insider’s Guide to

Jimmy Buffett. Secaucus, New Jersey, Carol Publishing, 1998.

Bugs Bunny

One of the most beloved animated characters of all time, Bugs

Bunny proved the likable combination of casual and wise guy who

speaks insouciantly with a Brooklyn accent (voiced by Mel Blanc).

Bugs has been both comic aggressor and straight man, but his essence

is that he is always sympathetic, responding only to provocation (a

character wants to eat him, wants him as a trophy, as a good luck

piece, as an unwilling participant in an experiment, etc.). Bugs never

engages an opponent without a reason, but once he is engaged, it’s a

fight to the finish with Bugs the comic winner. He can be mischie-

vous, cunning, impudent, a rascally heckler, a trickster, saucy, and

very quick with words, but he is never belligerent and prefers to use

his wits rather than resort to physical violence.

An embryonic version of Bugs first appeared in Ben Hardaway’s

1938 cartoon ‘‘Porky’s Hare Hunt,’’ in which the rabbit is a screwy

tough guy in the wacky and wild tradition of early Daffy Duck. The

character is given a screwball, Woody Woodpecker kind of laugh,

hops about wildly, and even flies, using his ears as propellers. He has

Bugs’ penchant for wisecracks (‘‘Here I am, fatboy!’’), as well as

Bugs’ occasional appeals to sympathy (‘‘Don’t shoot!’’). He also

expresses Bugs’ later catchphrase (borrowed from Groucho Marx in

Duck Soup), ‘‘Of course you realize, this means war!’’ However, the

white hare is also more aggressively wacky than the later character

and would torment his opponents mercilessly.

The character was designed by former Disney animator Charlies

Thorsen, and although unnamed in the cartoon itself, was christened

Bugs Bunny because the design sheet for director Ben ‘‘Bugs’’

BUMPER STICKERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

384

Hardaway was designated ‘‘Bugs’ Bunny.’’ Hardaway also guided

the hare through his second outing (and his first in color) in ‘‘Hare-um

Scare-um.’’ Director Frank Tashlin alleged that ‘‘Bugs Bunny is

nothing but Max Hare, the Disney character in ’The Tortoise and the

Hare.’ We took it—Schlesinger took it, whoever—and used it a

thousand times.’’ While both are brash and cocky characters, Bugs

was both wilder and funnier, eventually developing into a very

distinctive character. Animator and later director Robert McKimson

redesigned Bugs Bunny into the modern figure seen in the 1990s.

Bugs faced a number of antagonists over the years, the most

famous being Elmer Fudd (voiced by Arthur Q. Bryan), a large-

headed hunter with a speech impediment. The pair were first teamed

by Charles ‘‘Chuck’’ Jones in ‘‘Elmer’s Candid Camera,’’ with

Elmer stalking the ‘‘wascally wabbit’’ with a camera instead of his

usual gun. The team was then appropriated by Fred ‘‘Tex’’ Avery for

‘‘A Wild Hare,’’ in which some of Bugs’ rougher edges were

softened to make him less loony and annoying. Avery also coined

Bugs’ signature opening line, ‘‘Eh, what’s up, Doc?’’ as a memorably

incongruous response to a hunter preparing to pepper him with bullets.

Bugs really hit his stride under the direction of Bob Clampett in

such cartoons as ‘‘Wabbit Trouble,’’ ‘‘Tortoise Wins by a Hare,’’

‘‘What’s Cooking, Doc?,’’ ‘‘Falling Hare,’’ and ‘‘The Old Grey

Hare.’’ Clampett’s Bugs was one of the funniest and wildest incarna-

tions of the character and is much more physical than he later became.

These cartoons were later compiled into a feature, Bugs Bunny

Superstar, where Clampett took sole credit for inventing Bugs Bunny.

This did not set well with Jones, who when it came time to assemble

The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie credited every Bugs Bunny

director except Clampett.

Director Friz Freleng specialized in pitting Bugs against Yo-

semite Sam, a runt-sized alter ego of Freleng himself equipped with

an oversized hat, eyebrows, and mustache. Freleng found that Elmer

Fudd was too sympathetic and wanted to create an outright villain in

Sam. Sam’s attempts to get the better of Bugs, the varmint, were

eternally and comically frustrated. Sam made his first appearance in

‘‘Hare Trigger,’’ and Freleng’s Bugs and Sam won an Academy

Award for their teaming in ‘‘Knighty Knight Bugs.’’

However, Bugs’ finest interpreter was Chuck Jones, who always

felt that the rabbit should be motivated to wreak his mischief by an

antagonist who tries to push the supposedly timid woodland creature

around. Jones found his conception of Bugs materializing in ‘‘Case of

the Missing Hare,’’ ‘‘Super-Rabbit,’’ and ‘‘Hare Conditioned.’’

Jones and gag man Michael Maltese created terrific comic sparks by

allowing Bugs to play straightman to the forever frustrated Daffy

Duck whose plans to get Bugs shot instead of himself constantly go

awry. Three titles stand out: ‘‘Rabbit Fire,’’ ‘‘Rabbit Seasoning,’’

and ‘‘Duck! Rabbit! Duck!’’

Jones also created the musically based classic Bugs cartoons

‘‘Long-Haired Hare,’’ ‘‘Rabbit of Seviolle,’’ ‘‘Baton Bunny’’ and

‘‘What’s Opera, Doc?’’ as well as using the character to parody the

conventions of fairy tales, science fiction, and other genres in

‘‘Haredevil Hare,’’ ‘‘Frigid Hare,’’ ‘‘Bully for Bugs,’’ ‘‘Beanstalk

Bunny,’’ and ‘‘Ali Baba Bunny.’’ These are among the funniest

cartoons ever created and ample reason for Bugs’ enduring popularity.

—Dennis Fischer

F

URTHER READING:

Beck, Jerry, and Will Friedwald. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies.

New York, Henry Holt, 1989.

Jones, Chuck. Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated

Cartoonist. New York, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1989.

———. Chuck Reducks. New York, Warner Books, 1996.

Lenburg, Jeff. The Great Cartoon Directors. New York, De Capo

Press, 1993.

Maltin, Leonard. Of Mice and Magic. New York, New American

Library, 1980.

Bumper Stickers

The bumper sticker was first used after World War II when new

developments in plastic materials led to the production of paper strips

with adhesive on the back which allowed them to be fastened onto car

bumpers. The first bumper stickers were used almost exclusively

during political campaigns to promote candidates and parties. This

continued until the mid-1960s when personal statements such as

‘‘Make Love, Not War’’ or ‘‘America—Love It Or Leave It’’ began

to appear. The bumper sticker has become a form of folk broadcast-

ing, allowing anyone who owns a car to send out a slogan or message

to anyone who happens to read it. Ranging from the serious to the

satirical, many of the popular messages which appear on bumper

stickers can offer valuable information about Americans’ attitudes

and concerns over religion, politics, regionalism, abortion, the envi-

ronment, or any other debatable issue.

—Richard Levine

F

URTHER READING:

Gardner, Carol W. Bumper Sticker Wisdom: America’s Pulpit Above

the Tailpipe. Oregon, Beyond Words Publishing, 1995.

Harper, Jennifer. ‘‘Honk if You Love Bumper Stickers.’’ Washington

Times. July 26, 1988, p. E1.

Bundy, Ted (1946-1989)

Ted Bundy, perhaps the most notorious serial killer in American

history, was executed amidst much media attention in Florida on the

morning of January 24, 1989, for the murder of a 12 year-old girl. At

the time of his execution, Bundy had also been convicted for the

murders of two Florida State University students and was confessing

to the murders of more than 20 other women across the length of the

United States. Investigators, however, suspect Bundy actually com-

mitted anywhere between 36 to 100 murders in a killing spree that

may have begun when he was a teenager in the Pacific Northwest and

ended in north Florida. The media spectacle and public celebration

outside the walls of the Florida death-house where Bundy was

executed climaxed a long-term public fascination with one of the

country’s most photogenic, charismatic, and seemingly intelligent

multiple murderers. Details of Bundy’s gruesome murders, his re-

markable escapes from police custody, and his ‘‘fatal attraction’’

for women have all managed to circulate throughout American

popular mythology.

Ted Bundy’s early history is at once ordinary and portentous.

Bundy was born Theodore Robert Cowell on November 24, 1946, to

Eleanor Louise Cowell in a home for unwed mothers in Burlington,

BUNDYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

385

A car encrusted with bumper stickers.

Vermont. Ostracized by community and family after her pregnancy

became an open secret, Louise traveled from her parents in Philadel-

phia to give birth to Ted, left him at the home in Burlington for a few

months to discuss Ted’s future with her family, and then finally

brought Ted back to the Cowell house. Three years after that, Louise

moved with Ted to Tacoma, Washington, to stay with his uncle Jack,

a man whose education and intelligence Bundy much admired as he

grew up. In Tacoma, Louise met and married a quiet man named

Johnnie Bundy, and Ted’s last name became Bundy. Much of the

literature on Bundy, both popular and academic, focuses on the fact

that his mother Louise was unwed and that the father’s identity to this

day remains a matter of conjecture. Bundy himself frequently

downplayed the significance of his illegitimacy to his chroniclers, but

he also on occasion implied how his youthful discovery that he was a

‘‘bastard’’ forever changed him.

Also debated in the extensive Bundy literature is the extent to

which emotional and/or physical abuse distorted his development. All

through the years of Bundy’s public notoriety, he and some of his

immediate family members insisted that, for the most part, his

childhood was a loving, harmonious time. Since a series of psychiat-

ric examinations of Bundy in the 1980s, however, doctors such as

Dorothy Lewis have brought to light more of Bundy’s early domestic

traumas and many have come to believe that Bundy was emotionally

damaged by witnessing his grandfather’s alleged verbal and some-

times physical rages against family members. In any event, it seems

clear that Bundy developed a fascination for knives and stories of

murder quite early in his life—as early as three years of age. During

his adolescence, Bundy became secretly obsessed with pornography,

voyeurism, and sexually violent detective magazines.

As Bundy matured into a young man, he consciously cultivated

an image or public face not dissimilar to how he perceived his uncle

Jack: refined, educated, witty, public spirited, and stylish. Early on, he

became active in community church events and the Boy Scouts. He

later achieved modest academic success in high school and college,

eventually attaining admission to law school. He became a worker for

the Washington State Republican Party, strongly impressing then

Governor Dan Evans. He manned the phone lines at a suicide

crisis center and (ironically) studied sexual assault for a Seattle

investigatory commission.

Much of Bundy’s image making seemed designed to manipulate

women in particular. Though the level of Bundy’s sex appeal has been

exaggerated and romanticized by the media, particularly in the highly

rated 1986 NBC television movie The Deliberate Stranger (where he

was played by handsome actor Mark Harmon), Bundy did engage in a

number of romantic relationships during his life. Again, it has become

standard in Bundy lore to focus on his relationship with a beautiful,

BUNDY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

386

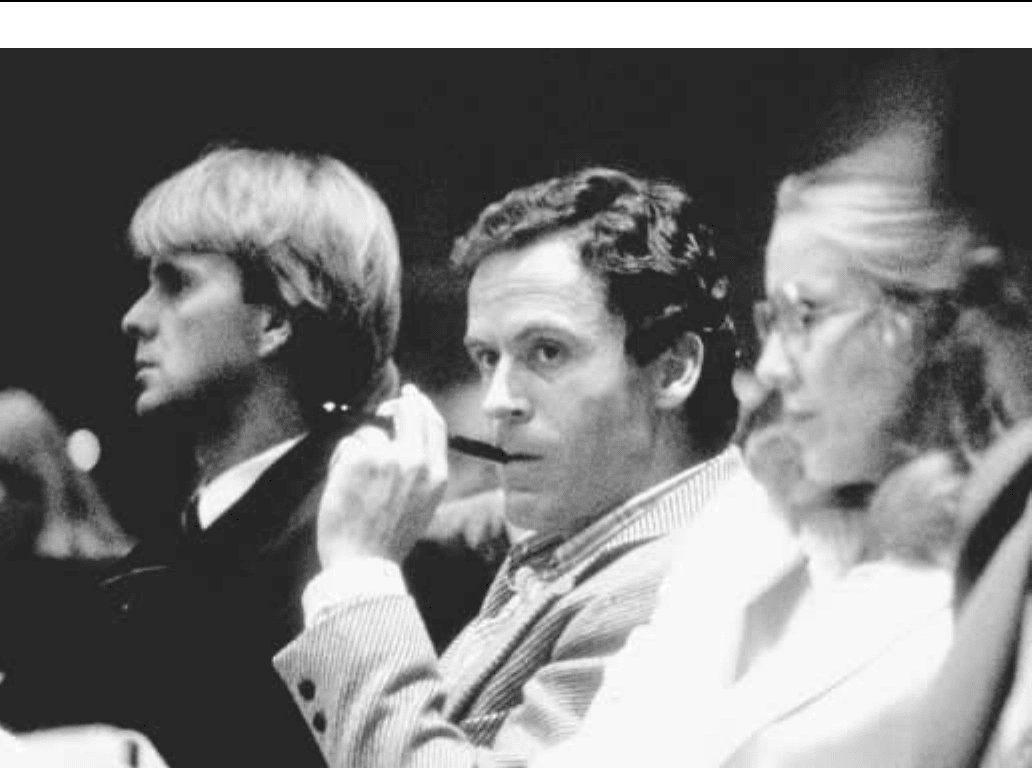

Ted Bundy (center) at his trial, 1979.

wealthy student when he was a junior in college. When the woman

jilted Bundy, he vowed to become the kind of sophisticated man who

could win her back. When they subsequently became engaged, Bundy

coldly rejected her. According to writers such as Ann Rule, this

woman is the physical and cultural prototype of Bundy’s victims, who

tended to be pretty, longhaired, and privileged co-eds. Another of

Bundy’s long-term lovers, a woman who wrote about her life with

Bundy under the penname of Liz Kendall, has become publicly

emblematic of the female intimates in Bundy’s life who were so

damaged by the revelation that he had killed dozens of women and yet

remain strangely compelled by the memory of his personality. Even

after his 1976 conviction for kidnapping a Utah woman brought

Bundy to the national spotlight as a suspected serial killer, he

continued to attract favorable female attention, eventually marrying a

woman named Carole Boone in a bizarre courtroom ceremony during

his second murder trial in 1980.

Bundy’s criminal career stretched from coast to coast. He began

murdering young college women in Washington State in 1974, either

by sneaking into their homes in the middle of the night to abduct and

kill them or by luring them with feigned helplessness and/or easy

charm from the safety of a crowd into his private killing zone. He next

moved on to Utah, where he attended law school by day and killed

women by night. He also committed murders in Colorado and Idaho

during this time. In August of 1975, Bundy was arrested for a traffic

violation and while he was in custody, police investigators from Utah

and Washington compared notes and realized that Bundy was a viable

suspect in the multi-state series of murders and kidnappings. Bundy

was convicted in the kidnapping and assault of a young Utah woman,

sent to prison, and later extradited to Colorado to stand trial for

murder. During a lull in the legal proceedings at a courthouse in

Aspen in 1977, Bundy escaped from an open window and remained

free for five days. Recaptured, Bundy again escaped six months later,

this time from a county jail. The second escape was not discovered for

hours—time enough for Bundy to be well on his way to his eventual

destination at Florida State University (FSU) in Tallahassee. At FSU,

Bundy killed two sorority women in the Chi Omega House and

shortly thereafter killed a 12 year-old girl in Lake City. These were

the last of Bundy’s murders.

Bundy’s arrest and conviction for the Florida murders twice

earned him the death penalty: in 1979 and 1980. His appeals lasted for

years, but it became apparent in late 1988 that Bundy would be

executed in January of 1989. In a desperate ploy to buy more time,

Bundy began confessing details of select murders to investigators

from across the country, including Robert Keppel, one of the original

detectives assigned to Bundy’s murders in the Pacific Northwest.

Bundy also granted a widely publicized videotaped interview to

BURGER KINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

387

evangelist James Dobson, during which Bundy blamed the pernicious

influence of pornography for the murders. In spite of the last-minute

confessions, however, Bundy was executed in ‘‘Old Sparky,’’ Flori-

da’s electric chair, as a mob of spectators outside Raiford Prison

waved signs with such slogans as ‘‘Burn Bundy Burn’’ and ‘‘Chi-O,

Chi-O, It’s Off to Hell I Go.’’

—Philip Simpson

F

URTHER READING:

Kendall, Elizabeth. The Phantom Prince: My Life with Ted Bundy.

Seattle, Madrona, 1981.

Keppel, Robert D., and William J. Birnes. The Riverman: Ted Bundy

and I Hunt for the Green River Killer. New York, Pocket

Books, 1995.

Larsen, Richard W. Bundy: The Deliberate Stranger. New York,

Pocket Books, 1986.

Michaud, Stephen G., and Hugh Aynesworth. The Only Living

Witness: A True Account of Homicidal Insanity. New York,

Signet, 1984.

———. Ted Bundy: Conversations with a Killer. New York,

Signet, 1989.

Rule, Ann. The Stranger Beside Me. New York, Signet, 1981.

Winn, Steven, and David Merrill. Ted Bundy: The Killer Next Door.

New York, Bantam, 1980.

Bungalow

Though we may say so of the American ranch house, the

bungalow serves as the archetypal style of American housing. As

ideas of homemaking and house planning took shape around the turn

of the twentieth century, designers sought a single style that embodied

the evolving American ideals in a form that could be dispersed

widely. While the sensibility of home design may have seemed

modern, it in fact grew out of a regressive tradition known as the Arts

and Crafts movement. The bungalow—meaning ‘‘in the Bengali

style’’—with its simplicity of design and functionality of layout,

proved to be the enduring product of modernist thought combined

with traditional application.

In the late nineteenth century, massive industrial growth cen-

tered Americans in cities and often in less than desirable abodes. The

arts and crafts movement argued for society to change its priorities

and put control back in human hands. One of the most prominent

popularizers of the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States

was Gustav Stickley. Inspired by William Morris and others, Stickley

began publishing The Craftsman in 1901 in hopes of initiating a social

and artistic revolution. Reacting against industrialization and all of its

trappings (from tenement squalor to the dehumanization of labor),

Stickley offered readers designs for his well-known furniture and

other materials—all handmade. The plans in The Craftsman led

naturally to model houses, featuring both interior and exterior plans.

The Stickley home, wrote the designer-writer, was a ‘‘result not of

elaborating, but of elimination.’’ Striking a Jeffersonian chord, Stickley

sought a design that would fulfill what he called ‘‘democratic

architecture’’: a way of living for all people. The design for this

unpretentious, small house—usually one-storied with a sloping roof—

became known as bungalow and would make it possible for the vast

majority of Americans to own their own home.

The homes of such designs played directly into a growing

interest in home management, often referred to as home economics.

At the turn of the twentieth century, American women began to

perceive of the home as a laboratory in which one could promote

better health, families, and more satisfied individuals with better

management and design. The leaders of the domestic science move-

ment endorsed simplifying the dwelling in both its structure and its

amenities. Criticizing Victorian ornamentation, they sought some-

thing clean, new, and sensible. The bungalow fulfilled many of these

needs perfectly.

While popular literature disseminated such ideals, great Ameri-

can architects also attached the term to the greatest designs of the

early 1900s. Specifically, brothers Charles and Henry Green of

California and the incomparable Frank Lloyd Wright each designed

palatial homes called bungalows. Often, this terminology derived

from shared traits with Stickley’s simple homes: accentuated

horizontality, natural materials, and restraint of the influence of

technological innovation. Such homes, though, were not ‘‘democrat-

ic’’ in their intent.

The most familiar use of ‘‘bungalow’’ arrived as city and village

centers sprawled into the first suburbs for middle-class Americans,

who elected to leave urban centers yet lacked the means to reside in

country estates. Their singular homes were often modeled after the

original Stickley homes or similar designs from Ladies’ Home

Journal. Housing the masses would evolve into the suburban revolu-

tion on the landscape; however, the change in the vision of the home

can be traced to a specific type: the unassuming bungalow.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Clark, Clifford Edward, Jr. The American Family Home. Chapel Hill,

University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream. Cambridge, MIT Press, 1992.

Burger King

Burger King is a fast-food restaurant franchise that, along with

McDonald’s, has come to typify the U.S. ‘‘hamburger chain’’ con-

cept that saw thousands of identical outlets spring up along the

nation’s highways after World War II and, later, in cities and towns

from coast to coast and around the world. With its orange-and-white

signs, Burger King, the ‘‘Home of the Whopper,’’ was founded in

Miami in 1954 by James McLamore and David Edgerton. Its first

hamburgers were sold for 18 cents, and its flagship burger, the

Whopper, was introduced in 1957 for 37 cents. Opened a year before

rival McDonald’s was franchised, Burger King was the first among

the fast food drive-ins to offer indoor dining. By 1967, when the

Pillsbury Corporation bought the company, there were 274 Burger

King restaurants nationwide, employing more than 8,000 people. As

of the end of 1998, there were 7,872 restaurants in the United States

and 2,316 in more than 60 countries selling 1.6 billion Whopper

sandwiches each year. Despite complaints from nutritionists about

the fatty content of fast-food meals, many time-pressed consumers

prefer them for their convenience and economy.

BURLESQUE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

388

Burger King carved out its own niche in fast-food merchandis-

ing by means of several factors: its distinctive Whopper product, a

cooking method that relies on flame-broiling instead of frying, and

the company’s aggressive and creative advertising campaigns. Even

so, Burger King remains a distant second to its chief competitor,

holding only 19 percent of the market compared to McDonald’s 42

percent. The two fast-food giants have long had an ongoing rivalry,

each claiming superior products, and even marketing competitive

versions of each others’ sandwiches. One of Burger King’s most

successful advertising campaigns in the 1970s mocked the uniformity

and inflexibility of its rival’s fast-food production with the slogan,

‘‘Have it Your Way,’’ implying that customized orders were more

easily available at Burger King than at McDonald’s.

In 1989, Pillsbury was bought by a British firm, Grand Metro-

politan (now Diagio), which acquired Burger King in the bargain.

Knowing little about the American tradition of fast food, the British

corporation tried to ‘‘improve’’ on the burger/fries menu by offering

sit-down dinners with waiters and ‘‘dinner baskets’’ offering a variety

of choices. This well-intentioned idea sent profits plummeting, and

Burger King did not truly recover for nearly a decade. Also in the late

1990s, Burger King, in cooperation with government attempts at

welfare reform, joined an effort to offer employment to former

welfare clients. Critics pointed out that fast-food restaurant jobs in

general are so low-paid and offer such little chance of advancement

that their usefulness to individual workers is limited. Occasionally the

defendant in racial discrimination suits, the corporation that owns

Burger King was taken to task in 1997 by the Congressional Black

Caucus for discriminatory practices against minority franchise own-

ers. The company has increased its investments in African-American

banks and its support for efforts of the fledgling Diversity Foods in

Virginia in its efforts to become one of the largest black-owned

businesses in the United States.

Despite Burger King’s second position after McDonald’s, the

market for fast food is large. Perhaps one of Burger King’s own past

slogans sums up the outlook of the franchise best, ‘‘America loves

burgers, and we’re America’s Burger King.’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

McLamore, James W. The Burger King: Jim McLamore and the

Building of an Empire. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Burlesque

The word ‘‘burlesque’’ can refer either to a type of parody or to a

theatrical performance whose cast includes scantily-clad women. The

second art form grew out of the first: ‘‘burla’’ is Italian for ‘‘trick,

waggery,’’ and the adjective ‘‘burlesca’’ may be translated as ‘‘ludi-

crous.’’ Borrowed into French, ‘‘burlesque’’ came to mean a takeoff

on an existing work, without any particular moral agenda (as opposed

to satire). The genre enjoyed a robust life on the French stage

throughout the nineteenth century, and found ready audiences in

British theaters as well.

The first American burlesques were imports from England, and

chorus lines of attractive women were part of the show almost from

the start. In 1866, Niblo’s Garden in New York presented The Black

Crook, its forgettable plot enlivened, as an afterthought, by some

imported dances from a French opera, La Biche au bois. Public

reception was warm, according to burlesque historian Irving Zeidman:

‘‘The reformers shrieked, the ’best people’ boycotted it,’’ but the

bottom line was ‘‘box receipts of sin aggregating over $1,000,000 for

a profit of $650,000.’’ The show promptly spawned a host of

imitations—The Black Crook Junior, The White Crook, The Red

Crook, The Golden Crook—capitalizing shamelessly, and profitably,

on Niblo’s success.

Two years later an English troupe, Lydia Thompson and Her

Blondes, made their New York debut at Woods’ Museum and

Menagerie on 34th St., ‘‘sharing the stage,’’ writes Zeidman, ‘‘with

exhibitions of a live baby hippopotamus.’’ The play this time was

F.C. Burnand’s classical travesty Ixion, in which the chorus, cos-

tumed as meteors, eclipses, and goddesses, thrilled the audience by

flashing their ruffled underpants in the Parisian can-can style.

The Thompson company was soon hired away to play at Niblo’s

in an arabesque comedy called The 40 Thieves. The orientalist turn

soon worked its way into other shows, including those of Madame

Celeste’s Female Minstrel Company, which included numbers such

as ‘‘The Turkish Bathers’’ and ‘‘The Turkish Harem.’’ (Even as late

as 1909, Millie De Leon was being billed as ‘‘The Odalisque of the

East,’’ i.e., the East Coast.) Orientalism was just one avenue down

which American burlesque in the last three decades of the nineteenth

century went in search of its identity in a tireless quest for plausible

excuses to put lots of pretty women on stage while still managing to

distinguish itself from what were already being called ‘‘leg shows.’’

Minstrelsy and vaudeville were fair game; so were ‘‘living pictures,’’

in which members of the troupe would assume the postures and props

of famous paintings, preferably with as little clothing as could be

gotten away with. (This method of art-history pedagogy was still

being presented, with a straight face, half a century later as one of the

attractions at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.)

By the turn of the century, burlesque shows could be seen on a

regular schedule at Manhattan’s London Theatre and Miner House

and across the East River in Brooklyn at Hyde and Behman’s, the

Star, and the Empire Theatres. Philadelphia offered burlesque at the

Trocadero, 14th Street Opera House, and the Arch, Kensington, and

Lyceum Theatres. Even staid Boston had burlesque at the Lyceum,

Palace, and Grand Theatres as well as the Howard Atheneum, where

young men who considered themselves lucky to catch a glimpse of an

ankle if they stood on street corners on rainy days (according to

Florence Paine, then a young businesswoman in the Boston shoe

trade), ‘‘could go to see women who wore dresses up to their knees.’’

(And wearing tights; bare legs would not come until later, even in

New York.)

A ‘‘reputable’’ burlesque show of the Gay Nineties, according to

Zeidman, might have a program such as was offered by Mabel

Snow’s Spectacular Burlesque Company: ‘‘New wardrobes, bright,

catchy music and pictures, Amazon marches, pretty girls and novelty

specialty acts.’’ By 1917, according to Morton Minsky (proprietor, as

were several of his brothers, of a famous chain of New York

burlesque houses) the basic ingredients of burlesque were ‘‘girls,

gags, and music.’’ Minsky describes in detail the first time he saw one

of his brothers’ burlesque shows at the Winter Garden that year, the

first half of which included a choral number (with much kicking of

legs in unison, Minsky notes), a comedy skit, a rendition of Puccini’s

‘‘Un bel di,’’ a turn by a ‘‘cooch dancer’’ (or hootchy-kootch,

vaguely derived from Near Eastern belly dancing and the prototype of

what would later be called ‘‘exotic dancing’’), a serious dramatic

sketch about a lad gone wrong who commits suicide, a second chorus,