Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BUTKUSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

399

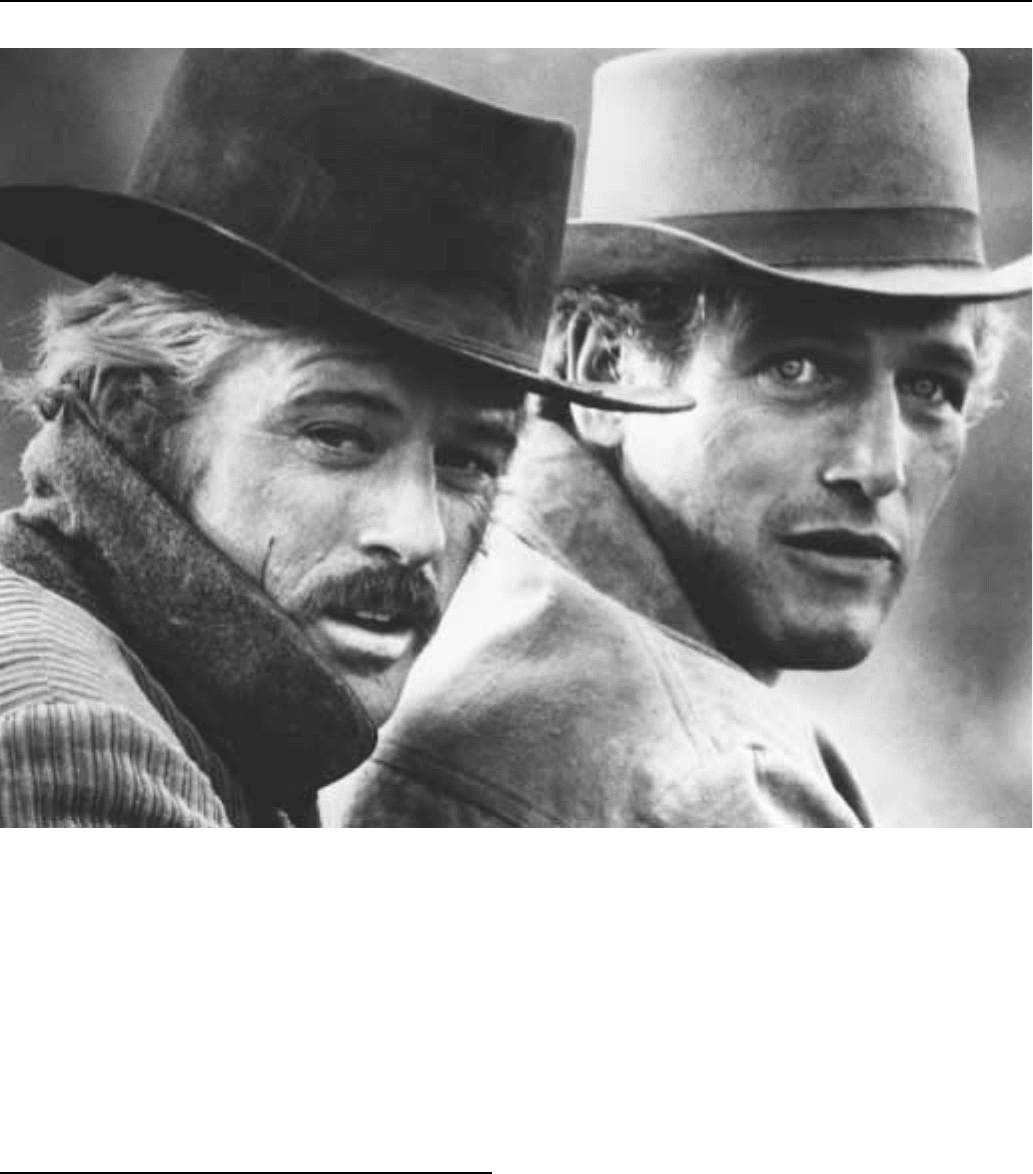

Robert Redford (left) and Paul Newman in a scene from the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

FURTHER READING:

Goldman, William. Adventures in the Screen Trade. New York,

Warner Books, 1983.

———. Four Screenplays with Essays. New York, Applause

Books, 1995.

Wukovits, John. Butch Cassidy. New York, Chelsea House Publish-

ing, 1997.

Butkus, Dick (1942—)

If a Hollywood scriptwriter were authoring a football movie and

needed to conjure up an ideal name for a hard-nosed middle lineback-

er who breakfasted on nails and quarterbacks, he could do no better

than Dick Butkus. Not only was Butkus, who played in the National

Football League between 1965 and 1972, the dominant middle

linebacker of his era, but he singlehandedly redefined the position.

What made him extra-special was his well-earned reputation for

being one of the toughest and most feared and revered players ever to

play the game. Butkus also brought a high level of intelligence and

emotion to the playing field, which only embellished his physical talents.

If the stereotypical quarterback is a pretty boy who comes of age

in a sun-drenched Southern California suburb, Butkus’ background

fits that of the archetypal dirt-in-your-fingernails linebacker or tackle:

he grew up on Chicago’s South Side, as the ninth child in a blue-collar

Lithuanian family. He attended the University of Illinois, where he

won All-America honors in 1963 and 1964; in the latter year, he was a

Heisman Trophy runner-up. In 1965, the 6′3″, 245-pounder was a

first-round draft pick of the Chicago Bears. During his nine-year

career with the Bears, which ended prematurely in 1973 due to a

serious knee injury, Butkus had 22 interceptions, was All-NFL for

seven years, and played in eight Pro Bowls.

On the football field he was all seriousness, and a picture of non-

stop energy and intensity. Butkus would do whatever was necessary

to not just tackle an opponent but earn and maintain everlasting

respect. He was noted for his ability to bottle up his anger between

Sundays, and free that pent-up fury on the playing field. Occasionally,

however, he was not completely successful in this endeavor, resulting

in some legendary alcohol-soaked escapades involving his pals and

teammates along with tiffs with sportswriters and in-the-trenches

BUTLER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

400

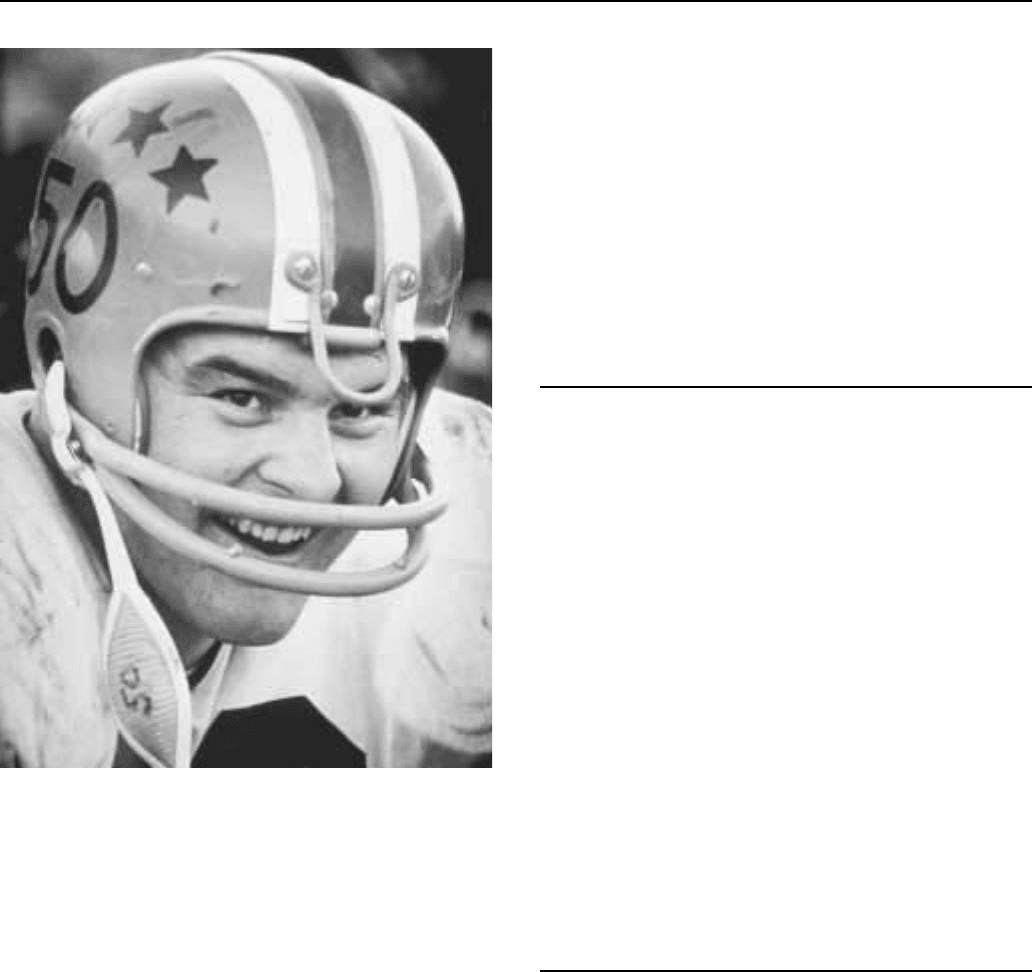

Dick Butkus

haggling with Bears owner-coach George Halas. Of special note is his

long-standing feud with Dan Jenkins of Sports Illustrated, who wrote

a piece in which he labeled Butkus ‘‘A Special Kind of Brute with a

Love of Violence.’’

After retiring from the Bears, Butkus became a football analyst

on CBS’s NFL Today and went on to a career as a television and film

actor. He would win no Oscar nominations for his performances in

Hamburger. . . The Motion Picture, Necessary Roughness and Grem-

lins 2: The New Batch, and no Emmy citations for My Two Dads, The

Stepford Children, Superdome and Half Nelson. But his grid creden-

tials remain impeccable. Butkus entered the Football Hall of Fame in

1979, and is described in his biographical data as an ‘‘exceptional

defensive star with speed, quickness, instinct, strength . . . great

leader, tremendous competitor, adept at forcing fumbles.... People

[still] should be talking about the way Dick Butkus played the game,’’

noted broadcaster and ex-NFL kicker Pat Summerall, over a quarter

century after Butkus’ retirement. Along with fellow linebackers Ted

Hendricks, Willie Lanier, Ray Nitschke, Jack Hamm, Jack Lambert,

and Lawrence Taylor, he was named to NFL’s 75th Anniversary Team.

Ever since 1985, the Dick Butkus Award has been presented to

the top collegiate linebacker. Herein lies Butkus’ gridiron legacy. To

the generations of football players in the know who have come in his

wake—and, in particular, to all rough-and-tumble wannabe defensive

standouts—Dick Butkus is a role model, an icon, and a prototypical

gridiron jock.

—Rob Edelman

F

URTHER READING:

Butkus, Dick, and Pat Smith. Butkus; Flesh and Blood: How I Played

the Game, New York, Doubleday, 1997.

Butkus, Dick, and Robert W. Billings. Stop-Action. New York,

Dutton, 1972.

Butler, Octavia E. (1947—)

As the premier black female science fiction writer, Octavia E.

Butler has received both critical and popular acclaim. She describes

herself as ‘‘a pessimist if I’m not careful, a feminist, a Black, a former

Baptist, an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecuri-

ty, certainty and drive.’’ Butler’s stories cross the breadth of human

experience, taking readers through time, space, and the inner work-

ings of the body and mind. She frequently disrupts accepted notions

of race, gender, sex, and power by rearranging the operations of the

human body, mind, or senses. Ironically, her significance has been

largely ignored by academics. Her notable books include Kindred,

Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Dawn and Parable of the Sower. She

has won the coveted Hugo and Nebula awards for ‘‘Speech Sounds’’

and ‘‘Bloodchild,’’ and in 1995 was awarded a MacArthur ‘‘Genius’’

grant for pushing the boundaries of science fiction.

—Andrew Spieldenner

F

URTHER READING:

Salvaggio, Ruth. Octavia Butler. Mercer Island, Washington, Starmont

House, 1986.

Butterbeans and Susie

The married couple Jodie (1895-1967) and Susie Edwards

(1896-1963), performing as Butterbeans and Susie, were among the

most popular African American musical comedy acts of the mid-

twentieth century. From 1917 until Susie’s death in 1963, they toured

regularly. Their act featured double entendre songs, ludicrous cos-

tuming, domestic comedy sketches, and Butterbeans’ famous ‘‘Hee-

bie Jeebie’’ dance. Racial segregation shaped their career in impor-

tant ways—their recordings were marketed as ‘‘Race’’ records, and at

their peak they played primarily in segregated venues. Their broad

humor exploited racial stereotypes in a manner reminiscent of min-

strel shows. Yet within the world of African American show business

such strategies were common, and clearly Butterbeans and Susie’s

antics delighted African American audiences. Butterbeans and Susie

achieved success by working with dominant racial images within the

discriminatory racial structures of America.

—Thomas J. Mertz

BUTTONSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

401

FURTHER READING:

Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in Blackface: A Source Book on Early

Black Musical Shows. Metuchen, New Jersey, The Scarecrow

Press Inc., 1980.

Buttons, Red (1919—)

In 1952, The Red Buttons Show was widely acclaimed as the

most promising new show on television, and its star was featured on

the cover of Time Magazine. Millions of children did their versions of

Buttons’s theme song, hopping and singing ‘‘Ho! Ho!, He! He!, Ha!

Ha! . . . Strange things are happening.’’ Indeed, strange things did

happen. By the end of the second season the show’s popularity had

declined and CBS dropped it. It did no better when NBC briefly

picked up the show the following season. Buttons was out of work in

1957 when he was selected to play the role of Sergeant Joe Kelly in

the film Sayonara. He won an Academy Award as best supporting

actor for this tragic portrayal and went on to appear in 24 other movies.

Born Aaron Chwatt in the Bronx borough of New York City in

1919 and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he was the son

of an immigrant milliner. He contracted the show business bug when

he won first place in an amateur-night contest at age 12. By age 16 he

was entertaining in a Bronx tavern as the bellboy-singer, and the

manager, noting his bright-colored uniform, gave him the stage name

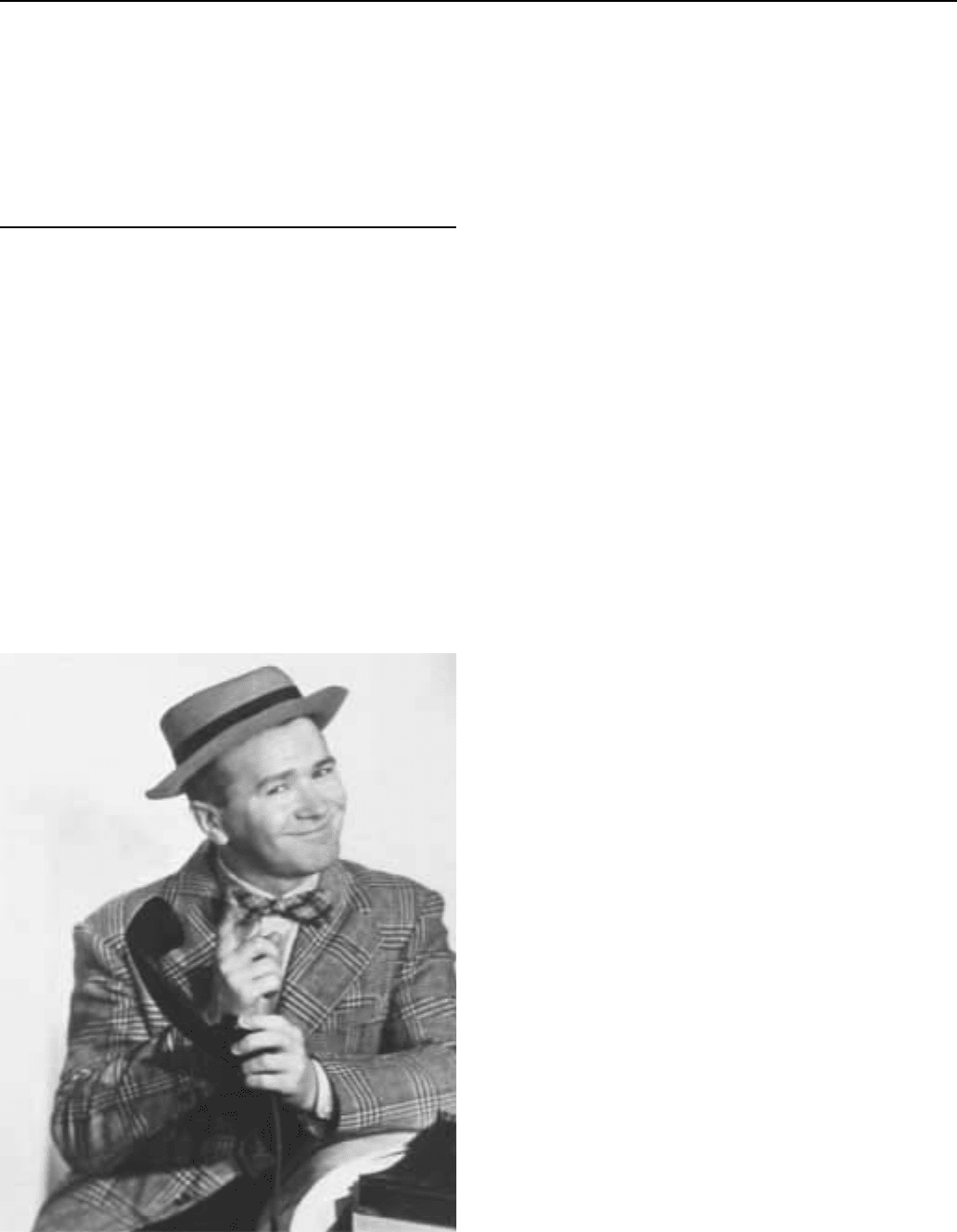

Red Buttons

of Red Buttons. Adding stand-up comedy to his talents, Buttons

worked in Catskill Mountain resorts and later joined a burlesque

troupe as a baggy-pants comic.

Buttons made his Broadway debut in 1942, playing a supporting

role in a show called Vickie. When he was drafted for World War II

service in the army, he was assigned to special services as an

entertainer. He appeared in the stage and film productions of Winged

Victory, a patriotic show designed to encourage the purchase of

war bonds.

When CBS offered a contract in 1952 for The Red Buttons Show,

a broad experience in show business had prepared Buttons well. He

had already developed some of his most popular characters—a

punchy boxer named Rocky Buttons, a lovable little boy named the

Kupke Kid, a hapless, bungling German named Keeglefarven, and the

jinxed, luckless Sad Sack. He also did husband-and-wife sketches

with Dorothy Joiliffe (later with Beverly Dennis and Betty Ann

Grove) in a style to be emulated by George Gobel in the late 1950s.

When the show moved to NBC, it started as a variety show, but

the format was soon changed to a situation comedy. Buttons played

himself as a television comic who was prone to get into all kinds of

trouble. Phyllis Kirk, later to become a star in Broadway musicals,

played his wife; Bobby Sherwood was his pal and television director,

and newcomer Paul Lynde played a young network vice president

who had continual disputes with the star. Dozens of writers worked on

the show at various times, but nothing seemed to click, and it was

scratched after one season.

After his Tony Award success with the movie Sayonara, But-

tons’s Hollywood career took off. Appearing in Imitation General,

The Big Circus, and One Two Three led in 1961 to a role in that year’s

Hollywood blockbuster, the film portrayal of the World War II

invasion of Normandy, The Longest Day. Buttons is remembered for

his portrayal of a lovable, sad sack paratrooper whose parachute is

impaled on a church steeple in a small French town, leaving him

hanging while the camera recorded his animated facial expressions.

He is also remembered for his comic role in the 1966 remake of

Stagecoach, starring Bing Crosby and Ann Margaret. He received an

Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor in 1969 for

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? This was a grim tale about a

marathon dance contest during the Great Depression. He was also

featured in the 1972 underwater disaster saga, The Poseidon Adventure.

Frequent guest spots on television talk shows and the continua-

tion of his film career as a both a comic and serious character actor

until 1990 kept Buttons before the public. He had an extended and

important career in show business, but some remember that on the

networks he was never able to fulfill the exalted promise of his first

show in its first season.

—Benjamin Griffith

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network TV Shows: 1946 to Present. New York,

Ballantine, 1981.

Inman, David. The TV Encyclopedia. New York, Perigee, 1991.

McNeil, Alex. Total Television: A Comprehensive Guide to Pro-

gramming from 1948 to the Present. New York, Penguin, 1991.

BYRDS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

402

The Byrds

The Byrds began as a folk-rock band in 1965 led by Jim

McGuinn (later renamed Roger following his conversion to Subud).

The harmonies arranged by David Crosby and McGuinn’s electric

twelve-string guitar gave them a rich, fresh sound. Often described as

the American Beatles, The Byrds were nevertheless distinctly origi-

nal. On their first two albums, Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn!

Turn! (1965), they covered Bob Dylan and traditional folk songs, and

wrote their own material. On ‘‘Eight Miles High’’ (1966) McGuinn

exhibited the influence of Indian ragas and the improvisational style

of John Coltrane. The Byrds explored a psychedelic sound on Fifth

Dimension (1966) and Younger than Yesterday (1967). They contin-

ued in the folk/psychedelic style on The Notorious Byrd Brothers

(1968), but Crosby left halfway through the recording of this album,

later forming Crosby, Stills, and Nash. The Byrds’ next album,

Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968), detoured into country-western.

Throughout the next five albums, the band suffered numerous person-

nel changes. McGuinn remained the only original member, but

somehow the newcomers persuaded him to continue recording coun-

try music and The Byrds abandoned their exploratory spirit. They

disbanded in 1973. Today The Byrds are remembered for the classics

of their folk and psychedelic period, some of which were immortal-

ized in the film Easy Rider (1969).

—Douglas Cooke

F

URTHER READING:

Fricke, David. Liner notes for The Byrds. New York, Columbia

Records, 1990.

Rogan, Johnny. Timeless Flight: The Definitive Biography of the

Byrds. London, Scorpion Publications, 1981.

403

C

Cabbage Patch Kids

The Cabbage Patch Kids doll-craze was an unprecedented

phenomenon among children and their parents that swept America

during the 1980s, reflecting, perhaps, the cultural leanings of an era

intent on expressing family values. By comparison with the Cabbage

Patch collecting mania, later collectors of the mass-marketed Beanie

Babies, Tamogotchis, and Tickle Me Elmos in the 1990s had it easy.

The 16-inch, soft-bodied Cabbage Patch dolls, the ultimate

‘‘must have’’ toy, were in such high demand during the 1983

Christmas season that the $25 retail Kids were ‘‘adopted’’ on the

black market for fees as high as $2,000. Toy manufacturer Coleco

Industries never expected that their homely, one-of-a-kind Kids—

complete with birth certificates and adoption papers—would be the

impetus behind department-store stampedes across the country, re-

sulting in sales of over six million dolls during their first nine months

on the market.

Xavier Roberts, a dollmaker in Columbus, Georgia, began

‘‘adopting’’ his Little People—soft-sculpture, handmade Cabbage

Patch prototypes—out of Babyland General Hospital in 1979. Rob-

erts’ gimmicks—from adoption papers and pledges, to hiring ‘‘doc-

tors’’ and ‘‘nurses’’ to deliver dolls from Babyland’s indoor Cabbage

Patch every few minutes to the delight of visitors—won his company,

A Cabbage Patch Kid complete with birth certificate.

Original Appalachian Artworks, a licensing deal with Coleco in late

1982. By the late 1980s, Roberts’ hand-signed Little People were

worth up to 60 times their original $75-200 cost. When Coleco filed

for bankruptcy in May 1988, Mattel (one of the manufacturers who

had passed on licensing rights to the dolls in 1982) took over the

Cabbage Patch license.

The mythos that Roberts created for his Cabbage Patch Kids—

born from a cabbage patch, stork-delivered, and happy to be placed

with whatever family would take them—encouraged the active

participation of parents and children alike, and fostered strong faith in

the power of fantasy, but the American public’s reaction to the dolls

was anything but imaginary. By virtue of their homely, one-of-a-kind

identities, and the solemnity with which buyers were swearing to

adoption pledges (due in no small part to the dolls’ scarcity), Cabbage

Patch Kids became arguably the most humanized playthings in toy

history: some ‘‘parents’’ brought their dolls to restaurants, high chair

and all, or paid babysitters to watch them, just as they would have

done for real children.

The psychological and social effects of the Kids of the Cabbage

Patch world were mixed. Adoption agencies and support groups were

divided over the advantages and disadvantages that the dolls offered

their ‘‘parents.’’ On one hand, they complained that the yarn-haired

dolls both desensitized the agony that parents feel in giving children

up for adoption, and objectified adoptees as commodities acquired as

easily as one purchases a cabbage. On the other hand, psychologists

such as Joyce Brothers argued that the dolls helped children and

adults alike to understand that we do not have to be attractive in order

to be loved. The dolls, proponents argued, helped erase the stigma that

many adopted children were feeling before the Kids came along.

When before Cabbage Patch Kids did American mass-market

toy consumers demand one-of-a-kind, personalized playthings? Who

since Xavier Roberts has been at once father, creator, publicist, and

CEO of his own Little ‘‘Family’’? Cabbage Patch Kids’ popularity

hinged on a few fundamental characteristics: a supercomputer that

ensured that no two Kids had the same hair/eye/freckle/name combi-

nation, Roberts’ autograph of authenticity stamped on each Cabbage

tush, an extended universe of over 200 Cabbage-licensed products,

and the sad truth that there were never enough of them to go around.

—Daryna M. McKeand

F

URTHER READING:

Hoffman, William. Fantasy: The Incredible Cabbage Patch Phe-

nomenon. Dallas, Taylor Publishing, 1984.

Sheets, Kenneth R., and Pamela Sherrid. ‘‘From Cabbage to Briar

Patch.’’ U.S. News and World Report. July 25, 1988, 48.

Cable TV

Considering the fact that in the late 1990s many experts view

existing television cables as the technological groundwork for what

may be the most important and far reaching media innovations since

CABLE TV ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

404

the printing press, the origins of cable television are quite humble. In

the early 1950s millions of Americans were beginning to regularly

tune in their television sets. However, a large number of Americans in

rural areas were not able to get any reception. Just as these folks

wanted TV, so too did television companies want them, for the more

people that watched, the more money the networks (ABC, CBS, and

NBC) and their advertisers made. Hence, the advent of community

antennae television (CATV), commonly known as ‘‘cable TV,’’ a

system in which television station signals are picked up by elevated

antennas and delivered by cables to home receivers. By the late 1990s

the majority of American households were cable subscribers. Be-

cause of cable’s rise to prominence, the ways in which Americans are

entertained have been irrevocably transformed. Furthermore, many

people think that in the twenty-first century new innovations utilizing

cable technology will lead to revolutionary changes in the ways in

which Americans live their daily lives.

In the early years of cable many saw it as an additional venue

through which to offer more viewing choices to consumers. But for

the most part, in the 1950s and 1960s the Federal Communications

Commission (FCC) was reluctant to grant licenses to cable operators,

ostensibly due to fear of putting the mostly local UHF stations out of

business. It is likely, however, that pressure on the FCC from the

networks, who didn’t want additional competition, also played a role

in the FCC’s reluctance to grant licenses to cable operators. While

there was some optimism about the possibilities for cable TV in the

early 1950s, in the early 1960s the progress of cable television was

slowed to a near standstill by a series of court cases. At issue was

whether or not the FCC had control over cable broadcasts, which were

transmitted through cables rather than airwaves. Cable companies

were literally pirating the broadcasts of local stations, which legiti-

mately threatened their existence. Although the cable industry won

some early cases, heavy pressure from the networks resulted in the

FCC declaring itself as having jurisdiction over cable broadcasts.

Cable companies fought the ruling, but the courts upheld it. The FCC

established prohibitive regulations that severely limited cable TV’s

growth potential, thus protecting the financial interests of local

stations and, more importantly, the networks.

However, in 1972 the FCC finally began allowing satellite

transmissions to be used by cable TV operators, which resulted in the

beginning of the cable revolution when a small Time Warner subsidi-

ary named Home Box Office (HBO) transmitted the motion picture

Sometimes a Great Notion over a cable system in Wilkes-Barre,

Pennsylvania. Although it would be three years before HBO became a

national presence, that first transmission altered forever the shape of

American television by paving the way for commercial cable service,

which first became widely available to consumers in 1976. Early

cable customers generally had to have a satellite dish in order to pick

up the signals. The dish provided a better picture than traditional TV,

as well as a greater number of stations, but it proved to be cost

prohibitive to too many customers for it to be financially successful.

Cable providers quickly adapted and created a system in which a

cable could be attached to just about anyone’s TV, provided one lived

in an area where cable TV was available. Providers soon realized that

most people would willingly pay a monthly fee for better reception

and more channels. Public demand for cable TV grew so fast that

companies could barely keep up with demand. In 1972 there were

only 2,841 cable systems nationwide. By 1995 that number had

grown to 11,215. Concurrently, the percentage of households sub-

scribing to cable service jumped from 16.6 percent in 1977 to nearly

70 percent in 1998.

By the mid-1970s the commercial possibilities of cable became

apparent. The problem for cable operators was how to attract an

audience to their channels when the networks were already free and in

nearly every home in America. Conversely, the networks could see

that cable would only become more prevalent. The question for them

was how could they get in on the cable bonanza. The solution was

both ingeniously simple and immensely profitable. The networks

agreed to sell their old shows to the cable networks, who would in turn

run them endlessly; thus was born the concept of ‘‘syndication.’’ For

a while this arrangement worked quite well. The networks, on the

basis of their original programming, continued to dominate the

market, especially during the lucrative 8 PM to 11 PM time slot

known as ‘‘Prime Time’’ because of the amount of people (consum-

ers) that watch during those hours. The cable networks were able to

enjoy profitability because even though they paid exorbitant franchise

fees for the rights to broadcast the networks’ old shows, they didn’t

have to invest in costly production facilities.

As a result of this arrangement between networks and cable

operators, an interesting thing happened among the American popu-

lace. Whereas previous generations of TV viewers were generally

only aware of the TV shows that originated during the lifetime,

beginning in the late 1970s Americans became TV literate in a way

they had never been before. Americans who came of age after the rise

of cable soon became generally conversant in all eras of television

programming. Fifteen year olds became just as capable of discussing

the nuances of The Honeymooners, I Love Lucy, and Star Trek as they

were the shows of their own era. Partly because of cable, television

trivia has become shared intelligence in America; however, this

shared cultural knowledge is not necessarily a good thing, for it has,

for many, been learned in lieu of a more traditional and useful

humanistic and/or scientific education. Accordingly, in the late 1990s

Americans are collectively more uninformed about the world in

which they live than at any other time in the twentieth century, which

can be attributed at least in part to the fact that most Americans spend

much more time watching TV than they do reading all forms of

printed media combined. Cable was originally thought to have great

potential as an educational tool. But even though there are a few cable

networks that educate as well as entertain, for the most part cable

stations are just as subservient to advertising dollars as their network

counterparts. As a result, advertising dollars play a large role in

dictating the direction of cable programming, just as they do on

network television.

For a number of years cable networks were content to run a

combination of old network programming, a mix of relatively new

and old Hollywood movies, and occasional pay-per-view events such

as concerts and sporting events. The first cable network to gain a

national foothold was Ted Turner’s TBS ‘‘Superstation,’’ which ran a

format similar to that of the networks, sans original programming. But

by the early 1980s it became clear to most cable operators that in order

to achieve the financial success they desired cable channels were

going to have to come up with their own programming. Thus was born

the greatest period of television programming innovation seen to that

point. Since their ascent to television dominance in the early 1950s,

the networks attempted to appeal to as a wide a general audience as

possible. The cable networks correctly assumed that they couldn’t

compete with the networks by going after the same type of broad

audience. Instead, they followed the example set by radio after the rise

of television in the early 1950s: they developed specific subject

formats that mixed syndicated and original programming and attract-

ed demographically particular target audiences for their advertisers.

CABLE TVENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

405

Americans quickly had access to an unprecedented quantity of

television stations; unfortunately, in most cases television’s quality

did not rise concurrently.

Nevertheless, many of the resulting stations have contributed

significantly to the direction of American popular culture. The herald

of cable TV’s importance to popular culture was a channel known as

Music Television, or MTV. Started in 1981, its rise to success was as

meteoric as it was astonishing. For American youth MTV became

their network, the network that provided the soundtrack for the trials

and tribulations of youths everywhere. Michael Jackson and Madon-

na’s status as cultural icons would not be so entrenched were it not for

their deft use of MTV as a medium for their videos. Beavis and

Butthead would have never caused such a ruckus among concerned

parents were it not for MTV. And the music industry, which was

flagging in the early 1980s, might not have survived were it not for

MTV, which was a virtual non-stop advertisement for recording

artists. Neither the ‘‘grunge’’ revolution started in the early 1990s by

the incessant playing of Nirvana’s ‘‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’’ video

nor the ensuing gangster rap, hip hop, and swing movements would

have occurred were it not for MTV. The trademark jump cutting

found in MTV videos has crossed over to become common place in

network television and Hollywood movies. But perhaps the most

important realization was for advertisers, who suddenly had unlimit-

ed access to a youthful audience never before thought to be a viable

consumer market. MTV’s audience specific success opened the

floodgates for the cable channels that followed.

Among the many cable channels that have made their mark on

American culture are the themed channels such as ESPN and ESPN 2,

Court TV, C-SPAN, The Weather Channel, Comedy Central, Black

Entertainment Television, The Animal Channel, Lifetime, Arts &

Entertainment, and the Food Channel. In addition, seemingly count-

less news channels have followed on the heels of Ted Turner’s Cable

News Network (CNN), which made its debut in 1980. There are also a

number of shopping channels, on which companies can not only hawk

their products, but sell them directly to the people as well. For

advertisers, cable has greatly increased access to the American

buying public, which has resulted in immense profits.

And yet, despite its inarguably providing countless and diverse

contributions to popular culture, ranging from the wall to wall

televising of O.J. Simpson’s murder trial and President Clinton’s

impeachment to a mainstream venue for South Park, The Simpsons,

and endless wrestling events, many find it difficult to characterize

cable’s overall contribution to American culture as positive. Clearly

television is an incredible medium for entertainment and advertising,

but as William F. Baker and George Dessart argue in Down the Tube:

An Inside Account of the Failure of American Television, that it

should be used almost exclusively for such purposes is a tragedy.

Regrettably, television’s potential as an educational tool has never

been realized. For every Ken Burns documentary there are a hundred

episodes of The Jerry Springer Show. As a result, the rise of cable has

only increased the size of the vast wasteland that is television.

After the success of so many cable stations, the networks

realized they were missing out on the financial gold mine. They

profited from the sale of their shows to cable networks, but the real

money came from ownership. However, it was illegal for a network to

own a cable system. But in 1992 the FCC dropped this regulation; the

networks could now own cable systems. What followed was literally

a feeding frenzy, as the networks both battled with each other to buy

existing cable networks and scrambled to start their own. What

resulted was the illusion of even greater choice for the American

viewing public. Although there were way more channels, there

weren’t appreciably more owners due to the fact that the networks

quickly owned many of the cable systems. Despite their claims to the

contrary, in actuality, in the late 1990s the networks controlled

television almost as much as they always had.

In 1992 Vice President Al Gore began singing the praises of

‘‘the information superhighway,’’ a synthesis of education, goods,

and services to be delivered through American televisions via existing

cable systems. Cable has always offered the possibility of two-way

communications. With the proper devices, Americans could send out

information through their cables as well as receive it. The technology

was not new, but its implementation was. Although at the time Gore

was considered by many to be a futuristic dreamer, industry insiders

quickly saw that two-way, or ‘‘interactive,’’ TV could be the wave of

the future. By incorporating interactive technology, cable TV could

transform American TVs into incredible machines capable of being a

TV, a computer, a superstore, a stereo, a library, a school, a telephone,

a post office, a burglar alarm, and a fire alarm all at once. However, a

relatively obscure computer network known as the ‘‘internet’’ al-

ready utilized two way phone lines to provide its users with interac-

tive ability. The phone companies saw the internet’s potential and

beat cable TV to the punch. By the late 1990s the internet was in as

many as half of all American homes and businesses. But phone lines

aren’t as effective at transferring information as cables. Fortunately

for the phone companies, FCC deregulation in the early 1990s made it

possible for them to own cable networks as well. Whether we want it

or not, it is just a matter of time before interactivity comes to

American televisions. But, judging by how fast and pervasively the

once free form internet became commercialized, it is hard to say

whether interactive TVs will change lives for the better or just

intensify the already oppressive amount of advertising to which

Americans are constantly subjected.

In addition to the networks and phone companies buying cable

networks, in the early 1990s other corporations began purchasing the

networks and phone companies. The reign of independent cable

mavericks such as Ted Turner gave way to a new age of corporate

cable barons. By the late 1990s cable and network television was

largely controlled by a half dozen massive media conglomerates, one

of which is Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., which owns countless

companies, including Twentieth Century Fox studios, the Los Ange-

les Dodgers, and Fox Television. The money making possibilities for

corporations like Murdoch’s are virtually endless. For example, Fox

TV not only features new episodes of its own original shows, such as

The X Files and The Simpsons, it also runs them endlessly once

they’re syndicated. The L.A. Dodgers frequently appear on Fox’s

Major League Baseball broadcasts. And Twentieth Century Fox

feature films routinely make their television debuts on Fox TV. All of

these activities result in profits for the parent company, Fox News

Corp. Furthermore, corporate ownership can threaten what integrity

TV has, as evidenced in the summer of 1998 when Disney, which

owns ABC, reportedly killed a negative ABC Nightly News story

about how Disney World’s lack of background checks resulted in

their hiring criminals. Although the ownership of television was

largely in the hands of relatively few monopolies, in the late 1990s

there was growing public and government rumblings about the

increasing ‘‘conglomeratization’’ of America, which led to the back-

lash and subsequent anti-trust case against Bill Gates’s Microsoft

CADILLAC ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

406

Corporation. But as of 1999 cable television’s many channels are in

the hands of a few and, despite appearances, Americans’ TV options

remain quite limited.

As James Roman writes in Love, Light, and a Dream: Televi-

sion’s Past, Present, and Future, the pioneers of cable television

‘‘could never have realized the implications their actions would come

to have on the regulatory, economic, and technological aspects of

modern communications in the United States.’’ In 1999 cable televi-

sion is America’s dominant entertainment and information medium,

and, due to the fact that 70 percent of Americans subscribe to some

form of cable TV, will remain so for the foreseeable future. For cable

subscribers, the future is approaching at breakneck speed. Without

consulting the public, the conglomerates have already made their

decisions concerning the direction of cable TV; in only a few short

years fully interactive television will almost certainly become a

reality and American life, for better or worse, will likely experience

changes in ways not yet imagined. And what about the 30 percent of

those for whom cable, either for financial or geographical reasons, is

not an option? Will they be able to compete in an increasingly

interactive world or will they be permanently left behind? Will the

advent of interactive TV create yet another social group, the techno-

logically disadvantaged, for whom a piece of the pie is not a realistic

aspiration? Is it at all possible that the people who have cable will defy

all prognostications and not embrace the new technologies that will

purportedly change their lives for the better? As of 1999 these remain

unanswerable questions but it is likely that the direction of American

popular culture in the early twenty-first century will be dictated by

their outcome.

—Robert C. Sickels

F

URTHER READING:

Baker, William F., and George Dessart. Down the Tube: An Inside

Account of the Failure of American Television. New York, Basic

Books, 1998.

Baldwin, Thomas F., D. Stevens McVoy, and Charles Steinfield.

Convergence: Integrating Media, Information & Communication.

Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications, 1996.

Baughman, James L. The Republic of Mass Culture: Journalism,

Filmmaking, and Broadcasting in America since 1941. Baltimore,

The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Bray, John. The Communications Miracle: The Telecommunication

Pioneers from Morse to the Information Superhighway. New

York, Plenum Press, 1995.

Davis, L. J. The Billionaire Shell Game: How Cable Baron John

Malone and Assorted Corporate Titans Invented a Future Nobody

Wanted. New York, Doubleday, 1998.

Dizard, Wilson, Jr. Old Media New Media: Mass Communications

in the Information Age. White Plains, New York, Longman

Press, 1994.

Frantzich, Stephen, and John Sullivan. The C-Span Revolution.

Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Roman, James. Love, Light, and a Dream: Television’s Past, Present,

and Future. Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 1996.

Whittemore, Hank. CNN: The Inside Story. Boston, Little, Brown, 1990.

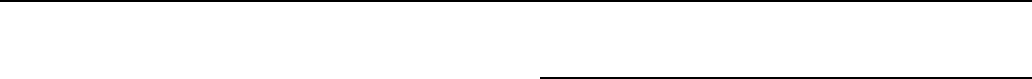

Cadillac

For several decades of the twentieth century, the Cadillac, a car

made by General Motors’ luxury automobile division, was the most

enduring symbol of middle-class achievement for status-conscious

Americans. Nowhere is the past and somewhat faded glory of the

Cadillac sedan more visible than in the affluent suburbs of Detroit,

where silver-haired retired automotive-industry executives and their

elegantly-coiffed wives, each stylized living relics of another era, can

still be seen tooling around in dark-hued Sevilles, while in other such

enclaves of prosperity across America, luxury cars from Germany

and Japan have long dominated this demographic.

The most popular luxury carmaker in the United States began its

history in 1902 in Detroit as one of the many new, independent

automobile companies in town. Founded by Henry Leland, who gave

it the name of the seventeenth-century French explorer who had

founded Detroit, Cadillac earned a devoted following with a reputable

and technologically innovative engine. Absorbed into the General

Motors family in 1909, the carmaker enhanced its reputation over the

years by numerous engineering achievements. For instance, Cadillac

was the first car company to successfully use interchangeable parts

that fit into the same model and did not require costly hand-tooling. In

1912, a new Cadillac was introduced with the Delco electric ignition

and lighting system. The powerful V-8 engine was also a Cadillac

first, and its in-house advertising director (the man who later founded

the D’Arcy MacManus agency), began using the advertising slogan

‘‘Standard of the World.’’ Another print ad, titled ‘‘The Penalty of

Leadership,’’ made advertising history by never once mentioning

Cadillac by name, a master stroke of subtlety.

Harley Earl, the legendary automotive designer, began giving

Cadillacs their elegant, kinetic look in the 1920s. He is credited with

introducing the first tailfin on the new designs in the late 1940s,

inspired in part by the fighter planes of World War II. A decade later,

nearly all American cars sported them, but Cadillac’s fins were

always the grandest. Purists despised them as style gimmicks, but the

public adored them. In the postwar economic boom of the 1950s the

Cadillac came to be viewed as the ultimate symbol of success in

America. They were among some of the most costly and weightiest

cars ever made for the consumer market: some models weighed in at

over 5,000 pounds and boasted such deluxe accoutrements as im-

ported leather seats, state-of-the-art climate and stereo systems, and

consumer-pleasing gadgets like power windows. The brand also

began to take hold in popular culture: Chuck Berry sang of besting

one in a race in his 1955 hit ‘‘Maybellene,’’ and Elvis Presley began

driving a pink Caddy not long after his first few chart successes.

Cadillac’s hold on the status-car market began to wane in the

1960s when both Lincoln and Chrysler began making inroads with

their models. Mismanagement by GM engendered further decline.

Cadillac production reached 266,000 cars in 1969, one of its peak

years. That model year’s popular Coupe DeVille (with a wheelbase of

over ten feet) sold for $5,721; by contrast the best-selling Chevrolet,

the Impala, had a sticker price of $3,465. There were media-generated

rumors that people sometimes pooled their funds in order to buy a

Cadillac to share. In the 1970s, the brand became indelibly linked

with the urban American criminal element, the ride of choice for

pimps and mob bosses alike. Furthermore, more affluent American

car buyers began preferring Mercedes-Benz imports, and sales of

CADILLACENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

407

The 1931 Cadillac

such German sedans (BMW and Audi also grew in popularity) began

to eclipse Cadillac. The car itself ‘‘became the costume of the

nouveau-riche—or the arrivistes, rather than those who enjoyed

established positions of wealth,’’ wrote Peter Marsh and Peter Collett

in Driving Passion: The Psychology of the Car. ‘‘People who are

busy clambering up the social ladder still imagine that those at the top

share their reverence for Cadillacs.’’

Combined with the spiraling away of the brand’s cachet, the

periodic Middle East oil crises of the decade made ‘‘gas guzzlers’’

such as the heavy V-8 Cadillacs both expensive and unfashionable.

Furthermore, mired in posh executive comfort and unable to respond

to the market, Detroit auto executives failed to direct the company

toward designing and making smaller, more fuel-efficient luxury

cars. Engineering flaws often plagued the few such models that were

introduced by Cadillac—the Seville, Cimarron, and Allante—and

gradually the brand itself began to be perceived as a lemon. GM

allowed Cadillac to reorganize in the early 1980s, and the company

somewhat successfully returned to the big-car market by the mid-

1980s, but by then had met with a new host of competition in the

field—the new luxury nameplates from the Japanese automakers,

Acura, Lexus, and Infinity.

Still, the Caddy remains a symbol of a particularly American

style and era, now vanished. When U.S. President Richard Nixon

visited the Soviet Union in May of 1972, he presented Premier Leonid

Brezhnev with a Cadillac Eldorado, which the Communist leader

reportedly very much enjoyed driving around Moscow by himself.

The Cadillac Ranch, outside of Amarillo, Texas, is a peculiarly

American art-installation testament to the make: it consists of vintage

Caddies partially buried in the Texas earth, front-end down.

—Carol Brennan

F

URTHER READING:

Editors of Automobile Quarterly Magazine. General Motors: The

First 75 Years of Transportation Products. Princeton, New Jersey,

Automobile Quarterly Magazine and Detroit, General Motors

Corporation, 1983.

Esquire’s American Autos and Their Makers. New York, Esquire, 1963.

Jorgensen, Janice, editor. Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands, Volume

3: Durable Goods. Detroit, St. James Press, 1994.

Langworth, Richard M., and the editors of Consumer Guide. Encyclo-

pedia of American Cars, 1940-1970. Skokie, Illinois, Publications

International, 1980.

Marsh, Peter, and Peter Collett. Driving Passion: The Psychology of

the Car. Boston, Faber, 1986.

CAESAR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

408

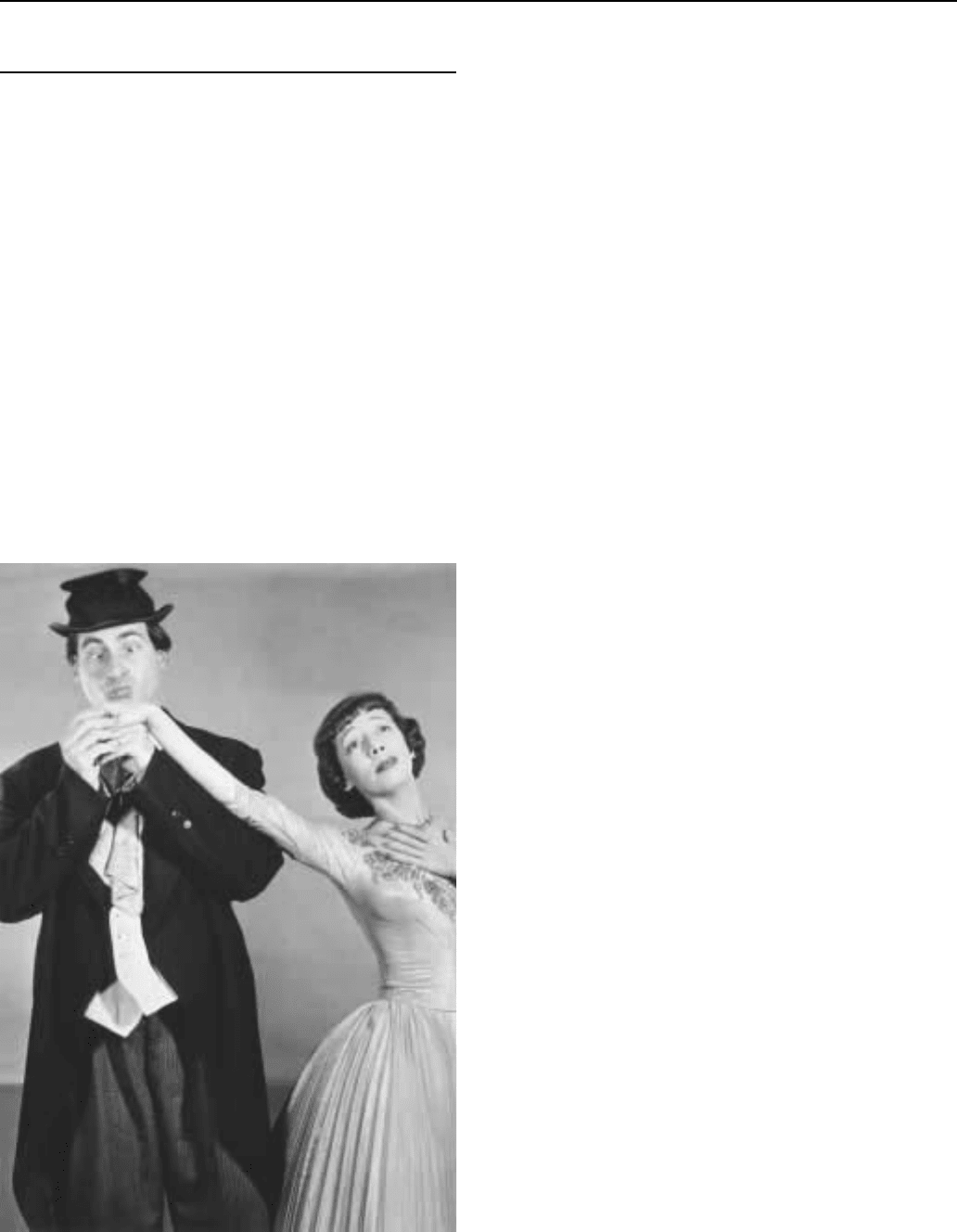

Caesar, Sid (1922—)

Sid Caesar was one of the most familiar and talented television

performers of the 1950s. His skills as a dialectician, pantomime, and

monologist made him a favorite of the critics and a fixture on

Saturday night television from 1950 to 1954. Along with co-star

Imogene Coca and a writing staff that included Carl Reiner, Mel

Brooks, Larry Gelbart, and a young Woody Allen, Caesar captivated

the new television audience with film parodies, characterizations, and

sitcom-style sketches on NBC’s Your Show of Shows. Caesar was also

infamous for his dark side, an apparent byproduct of his comedic

brilliance. A large man, carrying up to 240 pounds on his six-foot-

one-inch frame, articles in the popular press described his eating and

drinking habits as excessive and his mood as mercurial. In an age

when many top comedy television performers suffered physical and

mental breakdowns from the exacting demands of live television

production, Caesar stood out as a damaged man prone to self-

destruction and addiction. He was one of the first broadcast stars to

talk openly about his experiences in psychotherapy.

Surprisingly, Caesar did not begin his career in entertainment as

a comedian, but rather as a saxophonist. Brought up in Yonkers, New

York, by European Jewish immigrant parents, as a child Caesar

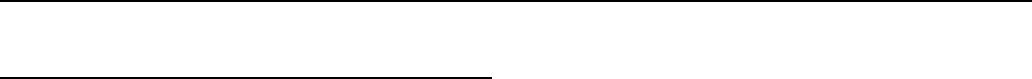

Sid Caeser and Imogene Coca

developed his abilities as a dialectician by mimicking the voices of

the Italian, Russian, and Polish émigrés who patronized his parents’

restaurant. But it was the customer who left behind an old saxophone

in the restaurant who had the most direct impact on Caesar’s career as

an entertainer. The young Caesar picked up the instrument and over

the years became an accomplished musician. After graduating from

high school, Caesar moved to Manhattan, played in various orches-

tras, and took summer work at Jewish hotels in the Catskills (com-

monly known as the ‘‘borscht belt’’). Although contracted as a

musician, he began to appear in the hotel program’s comedy acts as a

straight man and was so successful that he eventually decided to

emphasize his comedic skills over his musical talent.

Theatrical producer Max Liebman, who worked with Caesar on

revues in the Catskills and Florida, was central to Caesar’s entry into

the nascent medium of television. After years performing on stage, in

nightclubs, and in the Coast Guard recruiting show ‘‘Tars and Spars’’

(later made into a Hollywood film), the budding comedian was paired

with Imogene Coca in Liebman’s production ‘‘Admiral Broadway

Revue.’’ At Liebman’s prodding, NBC President Pat Weaver saw the

show, and he signed the entire cast and staff to do a television version

of their production under the same title. But the program’s sponsor,

Admiral, a major manufacturer of television sets, found the program

too expensive for its limited advertising budget. Weaver encouraged

Liebman to give television another try, using most of his original cast

and staff for a ninety-minute Saturday night program eventually titled

Your Show of Shows. Premiering in February of 1950 and following

on the heels of shows such as Texaco Star Theatre, Your Show of

Shows was conceived as a fairly straightforward vaudeville-style

variety program. However, with its talented cast and writing staff, the

show developed into more than just slapstick routines, acrobatic acts,

and musical numbers. Although ethnic jokes, borscht-belt-style mono-

logues, and sight gags were considered central to the success of early

variety programs, Caesar proved that these basics could be incorpo-

rated into a highly nuanced and culturally rich program that would

appeal to popular and high culture tastes simultaneously. His film

parodies and array of characters such as jazz musician Progress

Hornsby, the German Professor, and storyteller Somerset Winterset

became the most popular and memorable aspects of the show.

As a result of his unique talents, critics began to call Caesar

television’s Charlie Chaplin, and one usually tough critic, John

Crosby of the New York Herald Tribune, considered the comedian

‘‘one of the wonders of the modern electronic age.’’ Yet, despite such

ardent admiration, Caesar could not quiet the insecurities that had

plagued him since childhood. Known for his overindulgence of both

food and alcohol, it was said that Caesar would finish off a fifth or

more of Scotch daily. In an attempt to control his addiction, doctors

prescribed sedatives. However, the ‘‘cure’’ fueled the drinking habit

as Caesar took his medication with his daily dose of alcohol. This

combination intensified his bouts with depression and worsened the

quick temper that often revealed itself on the set or in writing meetings.

The season after Your Show of Shows ended its run in 1954,

Caesar immediately returned to television with Caesar’s Hour on

Monday nights on NBC. Although many of his problems were well-

known in the industry and by his fans, in 1956 he spoke on the record

about his emotional issues and subsequent entry into psychoanalysis

in an article in Look magazine. Claiming that analysis had cured him

of his depression and addiction, Caesar blamed his psychological