Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CAGNEYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

409

state on the emotional neglect of his parents during childhood. He

revealed that ‘‘On stage, I could hide behind the characters and

inanimate objects I created. Off stage, with my real personality for all

to see, I was a mess . . . I couldn’t believe that anyone could like me

for myself.’’

Despite his public proclamation of being cured, Caesar contin-

ued to suffer. After his second television program was taken off the air

in 1957 because it no longer could compete against ABC’s The

Lawrence Welk Show, the comedian’s mental and physical health

declined even further. Although he returned to television a few more

times during his career, he was never quite the same. During the 1960s

and 1970s he appeared in bit roles in movies such as Grease, History

of the World, Part I, and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but he

spent most of his time in isolation grappling with his problems. It

wasn’t until 1978 that he had completed his recovery. In his seventies

he continued to nurture a small but respectable movie career in The

Great Man Swap and Vegas Vacation, but he remained best known

as one of the most intelligent and provocative innovators of

television comedy.

—Susan Murray

F

URTHER READING:

Adair, Karen. The Great Clowns of American Television. New York,

McFarland, 1988.

Caesar, Sid. Where Have I Been? An Autobiography. New York,

Crown Publishers, 1982.

Caesar, Sid, as told to Richard Gehman. ‘‘What Psychoanalysis Did

for Me.’’ Look. October 2, 1956, pp. 49, 51-52.

Davidson, Bill. ‘‘Hail Sid Caesar!’’ Colliers. November 11, 1950,

pp. 25, 50.

Cagney and Lacey

The arrival of Cagney and Lacey in 1982 broke new and

significant ground in television’s ever-increasing proliferation of

popular cop series in that the stars were women—a pair of undercover

detectives out there with New York’s finest, unafraid to walk into the

threat of violence, or to use a gun when necessary. Effectively, writers

Barney Rosenzweig, Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday offered

audiences a female Starsky and Hutch, cleverly adapting the nuances

of male partner-and-buddy bonding to suit their heroines. Although

jam-packed with precinct life and crime action, the series was

character driven, with careful attention given to the private lives of the

two detectives, sharply contrasted for maximum interest in both the

writing and the casting. Mary Beth Lacey, dark-haired, New York

Italian working-class, combined her career with married life and the

struggle to raise her children; Christine Cagney, more sophisticated,

more ambitious, single, blonde, and very attractive, struggled with a

drinking problem. The relationships between them and their male

colleagues were beautifully and realistically brought to life by Tyne

Daly and Sharon Gless, respectively. Gless was a late addition,

brought in to counter criticisms that the show was too harsh and

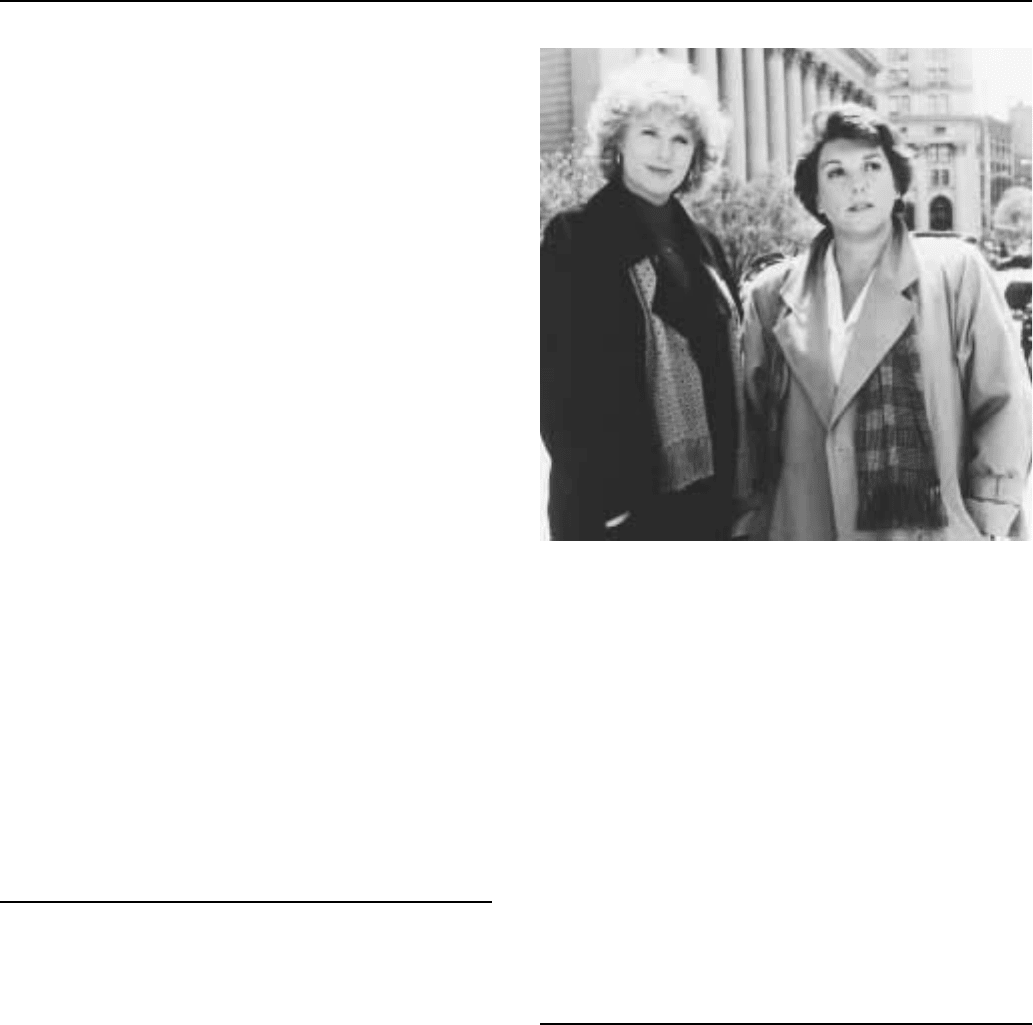

Sharon Gless (left) and Tyne Daly in a scene from the television movie

Cagney and Lacey: The Return.

unfeminine: Loretta Swit had played Cagney in the pilot, followed by

Meg Foster in the short first series, which failed to find favor in its

depiction of women in so unglamorous a context. However, with

Gless in tow, the show’s treatment of female solidarity and hard-

hitting issues won the CBS show a huge popular following, and lasted

for seven seasons until 1988.

—Nickianne Moody

F

URTHER READING:

Fiske, John. ‘‘Cagney and Lacey: Reading Character Structurally and

Politically.’’ Communication. Vol. 9, No. 3/4, 1987, 399-426.

Cagney, James (1899-1986)

One of the greatest tough-guy personas of twentieth-century

film, James Cagney worked hard to refine his image to meet his

responsible Catholic background. The result was a complex set of

characters who ranged from the hard-working immigrant striving to

make his way in America, to the American hero of Cold War times

who fought to preserve our way of life against Communist infiltrators.

Cagney’s various personas culminated in one as different from the

others as can be imagined—he began to play characters on the edge of

(in)sanity. It is his image as a tough guy, however, that is most enduring.

In 1933, during the filming of Lady-Killer, Darryl F. Zanuck sent

a memo to his crew of writers in which he detailed the studio’s

requirements for the Cagney persona: ‘‘He has got to be tough, fresh,

hard-boiled, bragging—he knows everything, everybody is wrong

but him—everything is easy to him—he can do everything and yet it

CAGNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

410

James Cagney in a scene from the film White Heat.

is a likeable trait in his personality.’’ During the 1930s, Cagney’s

uptempo acting style—the rat-a-tat-tat of his reedy voice—and his

distinctly Irish-puck appearance, created a decidedly lower-East side

aura. He was a city boy.

Cagney was born in New York City on July 17, 1899. Although

studio publicity promoted stories about a tough east-side upbringing

and life above a saloon, Cagney was, in fact, raised in the modest

middle-class neighborhood of Yorkville. Two of his brothers became

doctors. On screen, however, Cagney played tough guys—characters

who were immigrants fighting to fit in identified.

Public Enemy, Cagney’s first starring role, remains famous for

an enduring still of Cagney, with lips pursed, hair awry, and eyes

enraged, smashing a grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s face. But it was Tom

Powers’ contempt for assimilation that alarmed educators and re-

formers. In 1932, armed with the Payne Fund Studies, a group of

reformers feared that immigrant youths over identified with certain

screen stars and surrendered their parents’ values for falsely ‘‘Ameri-

canized’’ ones. In his popularization of the Payne report, Henry James

Forman echoed these fears when he identified one second-generation

Italian youth’s praise for Cagney: ‘‘I eat it. You get some ideas from

his acting. You learn how to pull off a job, how he bumps off a guy and

a lot of things.’’

Because of the uproar from reformers and the ascendancy of

President Roosevelt and his accompanying call for collective action,

Warner Brothers shifted their image of Cagney. He no longer embod-

ied lost world losers but common men fighting to make it in America.

And Cagney’s image of fighting to make it spoke to New York’s

immigrants (Italians, Jews, Poles, Slavs), who in 1930 comprised

54.1 percent of New York City’s households. From 1932-39 (a period

in which he made 25 films), Cagney represented an ethnic in-

between. As an Irish-American, he was an icon for immigrants

because he represented a complex simultaneity—he was both a part of

and apart from Anglo-Saxon society. In a series of vehicles, Cagney

was the outlaw figure, a character who did not want to conform to the

dictates of the collective, and yet, through the love of a WASPish

woman or the demands of the authoritative Pat O’Brien (the Irish cop

figure in Here Comes the Navy [1934] and Devil Dogs of the Air

[1935]) Cagney harnessed his energies to communal good.

CAKEWALKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

411

Regardless of how Cagney’s image was read by immigrants,

sociologists, and reformers, he was not happy with how he perceived

Zanuck and the Warner Brothers’ script writers had structured his

persona. A devout Catholic and a shy, soft-spoken man off-screen, he

was tired of roughing up women and playing street punks on screen.

Three times (1932, 1934, 1936) he walked off the studio lot to protest

his typecasting. In March 1936, Cagney won a breech of contract suit

against Warner Brothers, and later that year signed with Grand

National where he filmed Great Guy (1936) and Something to Sing

About (1937). Unfortunately, neither effort changed his persona, and

with Grand National falling into receivership, Cagney returned to

Warner Brothers.

To enhance Cagney’s return, Warner Brothers immediately

teamed him with old pal and co-star Pat O’Brien in Angels With Dirty

Faces (1938). As Rocky Sullivan, Cagney received an Academy

Award nomination and the New York Critics Award for best actor.

The film’s most memorable scene features Cagney’s death-row walk

in which his ‘‘performance’’ switches the Dead End Kids’ alle-

giances from one father figure (Cagney) to another (O’Brien). It is

an explosive moment of ambiguity in which a character destroys

his reputation for the audience in the film (the Kids) but gains,

through his sacrifice, saintliness from the audience in the theater

(largely immigrant).

By the 1940s, Cagney’s image had radically changed under the

pressures of the Martin Dies’ ‘‘Communist’’ innuendoes. With war

raging in Europe the competing images in Cagney’s persona (the

anarchic individual at odds with the collective; the Irish-American

trying to make it in WASP—White Anglo-Saxon Protestant—socie-

ty) were transformed into a homogenized pro-United States figure.

The plight of the immigrant was replaced by Warner Brothers’ all-

American front to the Axis. Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) culminated

the change as Cagney was galvanized into a singing, dancing super-

patriot. Cagney won an Academy Award for this dynamic performance.

Following a second try at independence (United Artists, 1943-

48), the post-World War II Cagney struggled to maintain a contempo-

rary persona. Much of his New York City audience had grown up and

moved to the suburbs. Too old and lace-curtain Irish to remain an

ethnic in-between, the post-war Cagney bifurcated into two types: a

strong-willed patriarch or a completely insane figure who needed to

be destroyed. White Heat mirrored the switch in emphasis. No longer

was Cody Jarret fighting to realize the immigrant dream; instead he

fought a mother complex.

On March 18, 1974 more than 50 million Americans watched

Cagney accept the American Film Institute’s second annual life-time

achievement award. Although he had fought Zanuck, Wallis, and the

studio’s construction of his ‘‘tough, fresh, hard-boiled’’ image, he

embraced it during the tribute. In his acceptance speech Cagney

thanked the tough city boys of his past: ‘‘they were all part of a very

stimulating early environment, which produced that unmistakable

touch of the gutter without which this evening might never have

happened.’’ James Cagney died on Easter Sunday, 1986.

—Grant Tracey

F

URTHER READING:

Forman, Henry James. Our Movie Made Children. New York,

MacMillan, 1933.

Kirstein, Lincoln (as Forrest Clark). ‘‘James Cagney.’’ New Theater.

December, 1935, 15-16, 34.

McGilligan, Patrick. Cagney: The Actor as Auteur. San Diego, A.S.

Barnes, 1982.

Naremore, James. Acting for the Cinema. Berkeley, University of

California Press, 1988.

Sklar, Robert. City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield. New Jersey,

Princeton University Press, 1992.

Tynan, Ken. ‘‘Cagney and the Mob.’’ Sight and Sound. May,

1951, 12-16.

Cahan, Abraham (1860-1951)

The flowering of Jewish-American fiction in the 1950s and

1960s had its origin in the pioneering work of Abraham Cahan:

immigrant, socialist, journalist, and fiction writer. With William

Dean Howells’ assistance, Cahan published Yekl: A Tale of the New

York Ghetto (1896) and The Imported Bridegroom (1898). But it is

The Rise of David Levinsky (1917) that is his masterwork. Using

Howells’s Rise of Silas Lapham as his model, Cahan explores an

entire industry (ready-made clothing) and immigrant experience

(Eastern European Jews) by focusing on a single character and his

bittersweet ascent from Russian rags to Manhattan riches. A major

work of American literary realism, The Rise of David Levinsky is also

an example of reform-minded Progessivism and began as a series of

sketches in McClure’s Magazine alongside the work of muckrakers

Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell. Although he is best remembered for

this one novel (rediscovered in 1960 thanks to the popularity of a later

generation of postwar Jewish-American writers), Cahan’s most influ-

ential act was the founding of the world’s leading Yiddish newspaper,

the Jewish Daily Forward, in 1902.

—Robert A. Morace

F

URTHER READING:

Chametsky, Jules. From the Ghetto: The Fiction of Abraham Cahan.

Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1977.

Marowitz, Sanford E. Abraham Cahan. New York, Twayne, 1996.

Cakewalks

An elegant and stately dance created by African slaves on

Caribbean and North American plantations, the cakewalk enjoyed a

long history. During slavery, plantation owners judged the dance and

the finest dancer was rewarded with a cake. It became the first

African-American dance to become popular among whites. The

cakewalk was features in several contexts including the minstrel show

finale, early black musicals including Clorindy, or The Origin of the

Cakewalk in 1898 and The Creole Show in 1899, and on ballroom

floors thereafter. The cakewalk embodied an erect body with a quasi-

shuffling movement that developed into a smooth walking step.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Cohen, Selma Jeanne, ed. International Encyclopedia of Dance. New

York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

CALDWELL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

412

Emery, Lynne Fauley. Black Dance in the United States from 1619 to

1970. Palo Alto, California, 1972.

Caldwell, Erskine (1903-1987)

Although Erskine Caldwell gradually descended into obscurity,

during his heyday in the 1930s and 1940s his books were perennial

best-sellers. Notorious for the explicit sexuality in his novels about

Southern poor whites, Caldwell withstood several obscenity trials and

saw his work banned on a regular basis. Caldwell’s trademark

mixture of sex, violence, and black humor garnered various reactions.

Southerners in particular felt that Caldwell pandered to stereotypes of

the South as a land of ignorance, sloth, and depravity, but many

respected literary critics saw burlesque humor, leftist political activ-

ism, or uncompromising realism in Caldwell’s writing. Caldwell’s

major fiction included Tobacco Road (1932), God’s Little Acre

(1933), Kneel to the Rising Sun and Other Stories (1935), Trouble in

July (1940), and Georgia Boy (1943). In addition to novels and short

stories, Caldwell coauthored a number of photograph-and-text books

with his second wife, photographer Margaret Bourke-White, the most

popular of which were You Have Seen Their Faces (1937) and Say, Is

This the U.S.A.? (1941).

Caldwell was born in rural White Oak, Georgia. He inherited his

social conscience from his father, a minister in the rigorous Associat-

ed Reformed Presbyterian Church. Because of his father’s ministry,

Caldwell’s family moved frequently, and their financial situation was

often strained. Caldwell had little formal education. His mother

taught him at home during his early childhood, and he never formally

graduated from high school. He later spent brief periods at three

different colleges but never obtained a degree. After a long series of

odd jobs and some newspaper work for the Atlanta Journal, Caldwell

moved to Maine in 1927 to concentrate on writing fiction. He would

never again live in the South, though he made occasional visits for

documentary projects or creative inspiration.

Caldwell’s early years in Maine were spent in utter poverty. His

first three books attracted little attention, but his fourth, Tobacco

Road, defined his career and made him rich. Published in 1932,

Tobacco Road featured Jeeter Lester and family, a brood of destitute

sharecroppers in rural Georgia. The dysfunctional Lester clan starved

and stole and cussed and copulated throughout the book, which

initially received mixed reviews and posted lackluster sales. Jack

Kirkland changed all that when he translated Tobacco Road into a

phenomenally successful Broadway play. The play ran from Decem-

ber of 1933 through March of 1941, an unprecedented seven-year

stretch that was a Broadway record at the time. Touring versions of

the play traveled the nation for nearly two decades, playing to packed

houses throughout the country. Caldwell’s book sales skyrocketed.

Through the 1940s Caldwell’s books continued to sell well in

dime-store paperback versions with lurid covers, but reviews of his

new books were increasingly harsh. Though he continued writing at a

prolific pace, Caldwell was never able to repeat the critical success of

his earlier work. The quality of his work plummeted, and his

relationships with publishers and editors, often strained in the past,

deteriorated further.

Despite Caldwell’s waning literary reputation, he had a lasting

impact on American popular culture. A pioneer in the paperback book

trade, he was one of the first critically acclaimed writers to aggres-

sively market his work in paperback editions, which were considered

undignified at the time. Most of Caldwell’s astonishing sales figures

came from paperback editions of books that were first published in

hardback years earlier. These cheap editions were sold not in bookstores,

but in drug stores and magazine stands; consequently they reached a

new audience that many publishers previously had ignored. Sexually

suggestive covers aided Caldwell’s sales and forever changed the

marketing practices for fiction. His censorship battles made Caldwell

a pivotal figure in writers’ battles for First Amendment rights.

Without question, however, Caldwell’s greatest legacy has been his

depiction of Southern poor whites. The Lesters have been reincarnat-

ed in The Beverly Hillbillies, Snuffy Smith, L’il Abner, The Dukes of

Hazzard, and countless other poor white icons. Though its origin

seems largely forgotten, the term ‘‘Jeeter’’ survives as a slang

expression for ‘‘poor white trash.’’

—Margaret Litton

F

URTHER READING:

Cook, Sylvia Jenkins. Erskine Caldwell and the Fiction of Poverty.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University, 1991.

MacDonald, Scott, editor. Critical Essays on Erskine Caldwell.

Boston, G. K. Hall, 1981.

Miller, Dan B. Erskine Caldwell: The Journey from Tobacco Road.

New York, Knopf, 1995.

Mixon, Wayne. Erskine Caldwell: The People’s Writer. Charlottes-

ville, University of Virginia Press, 1995.

Silver, Andrew. ‘‘Laughing over Lost Causes: Erskine Caldwell’s

Quarrel with Southern Humor.’’ Mississippi Quarterly. Vol. 50,

No. 1, 1996-97, 51-68.

Calloway, Cab (1907-1994)

Known as ‘‘The Hi-De-Ho Man,’’ jazz singer, dancer, and

bandleader Cab Calloway was one of the best-known entertainers in

the United States from the early 1930s until his death in 1994.

Calloway’s musical talents, however, were only part of the story.

His live performances at Harlem’s Cotton Club became legendary

because of Calloway’s wild gyrations, facial expressions, and

entertaining patter.

Born Cabell Calloway on Christmas Day, 1907, in Rochester,

New York, Calloway spent most of his childhood years in Baltimore.

The younger brother of singer Blanche Calloway, who made several

popular records in the early 1930s before retiring, Cab discovered

show business during his teen years, frequenting Chicago clubs while

attending that city’s Crane School. When Calloway encountered

financial difficulties, he naturally turned to moonlighting in the same

clubs, first as an emcee and later as a singer, dancer, and bandleader.

Although Calloway was attending law school and his hopes for a

career in that field looked promising, he elected to drop out and try to

make it as a singer and dancer. He led a successful Chicago group, the

Alabamians, who migrated to New York but found the competition

CALVIN AND HOBBESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

413

Cab Calloway

too harsh to survive. Calloway had better luck with his next group, the

Missourians, appearing in the Broadway revue Connie’s Hot Choco-

lates in 1929.

Soon after, Calloway was offered a position as the headline act at

the Cotton Club, and he readily accepted. He also had begun record-

ing, and in 1931 produced his best-known single, ‘‘Minnie the

Moocher.’’ Minnie and her companion, Smokey Joe, were the first of

many fictional characters Calloway invented to entertain his audi-

ences. He continued Minnie’s saga with such ‘‘answer’’ records as

‘‘Minnie the Moocher’s Wedding Day’’ and ‘‘Mister Paganini,

Swing for Minnie,’’ which took a satirical look at classical music. He

continued to develop his talents as a jazz singer and was one of the

first ‘‘scat’’ singers, improvising melodies while singing nonsense

lyrics. Blessed with a wide vocal range, Calloway employed it to his

fullest advantage, especially on his famous ‘‘hi-de-ho’’ songs, which

included ‘‘You Gotta Hi-De-Ho’’ and the ‘‘Hi-De-Ho Miracle Man.’’

Calloway’s orchestra was a showcase and proving ground for

some of the most prominent musicians in the history of jazz. Walter

‘‘Foots’’ Thomas, Doc Cheatham, Danny Barker, Dizzy Gillespie,

and Ike Quebec, among many others, gained notoriety by appearing

with Calloway, who paid higher salaries—and demanded better

work—than any other bandleader.

Calloway had so much visual appeal that he was cast in several

movies, including Stormy Weather (1943). More recently, Calloway

played a thinly veiled version of himself in the 1980 blockbuster The

Blues Brothers, dispensing fatherly advice to protagonists Jake and

Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd) as well as turning in a

spectacular performance of ‘‘Minnie the Moocher’’ at the film’s climax.

Although the single ‘‘Blues in the Night’’ was a major hit in

1942, Calloway found little commercial success after the Depression

years. With the end of the big-band era after World War II, Calloway

reluctantly disbanded his orchestra in 1948 and thereafter performed

solo or as a featured guest in other groups. His love of entertaining led

him to continue performing for fans until his death in 1994.

—Marc R. Sykes

F

URTHER READING:

Calloway, Cab, and Bryant Rollins. Of Minnie the Moocher and Me.

New York, Crowell, 1976.

Calvin and Hobbes

Imaginative, hilariously drawn, at times philosophical—all the

while retaining a child’s perspective— this daily and Sunday comic

strip has been compared to the best of the classic comics. Written and

drawn by Bill Watterson, Calvin and Hobbes debuted in 1985 and

featured the adventures of Calvin, a hyperactive, overly imaginative,

bratty six-year-old, and his best friend, the stuffed tiger Hobbes.

Other regularly appearing characters included Calvin’s stressed out

parents; Susie Derkins, the neighborhood girl; Miss Wormwood, the

much put-upon school teacher; Mo, the school bully; and Rosalyn, the

only baby-sitter willing to watch Calvin.

Part of the charm of the strip was the fact that Watterson often

blurred the distinction between what was imaginary and what was

‘‘real.’’ Calvin saw his tiger as real. When Calvin and Hobbes were

by themselves, Watterson drew Hobbes as a walking tiger with fuzzy

cheeks and an engaging grin. When another character appeared with

Calvin and Hobbes, Hobbes was drawn simply as an expressionless

stuffed tiger. The ‘‘real’’ Hobbes was more intellectual than Calvin

and also liked to get ‘‘smooches’’ from girls, unlike the girl-hating

Calvin (though both were founding members of G.R.O.S.S.—Get Rid

of Slimy girlS).

Unlike Dennis the Menace, Calvin and Hobbes went beyond the

hijinks of a holy terror. It explored childhood imagination and the

possibilities of that imagination. For instance, one of Calvin’s chief

toys besides Hobbes was a large cardboard box. When it was right

side up, the box was a time machine that transported Calvin and

Hobbes back to the Jurassic. When Calvin turned it over, the box

became the transmogrifier, which could transmogrify, or transform,

Calvin into anything he wished. The transmogrifier was later convert-

ed into a duplicator, producing lots of Calvins. Imagination sequences

such as these have been imitated by other comic strips such as Jim

Borgman and Jerry Scott’s Zits.

Calvin’s imaginary world contained other memorable characters

and devices. Calvin became the fearless Spaceman Spiff whenever he

needed to escape the doldrums of school or the rebuke of his parents,

who clearly loved but did not always like Calvin, a view of the family

different from many others seen on the comics page. Calvin would

don a cape and cowl and become Stupendous Man. His repertoire also

included a tyrannosaur, or Calvinosaur, a robot, and a werewolf.

Calvin also liked to sit in front of the television set, a behavior

Watterson satirized, evidencing his contempt of television as opposed

to personal imagination.

Most of the strips featured Calvin’s antics, such as hitting Susie

with a snowball or running away from his mother at bath time. Other

CAMACHO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

414

common gags included his reluctance to eat dinner, his hatred of

school and homework, and his antagonism toward Rosalyn. Calvin

also enjoyed building deformed or dismembered snowmen on the

front lawn. Besides these gags, though, the strip would at times deal

with the philosophical nature of humanity as seen by a child and a

tiger. Given the names of the characters, this was only to be expected.

The comic strip’s title characters are named after John Calvin and

Thomas Hobbes. Calvin was a Protestant reformer famous for his

ideas on predestination and the sovereignty of God. Calvin believed

men, and children, to be sinners. Hobbes, author of the Leviathan,

believed in submission to the sovereign of the state, since he too

believed men were evil. Watterson occasionally commented on such

issues between his two characters, usually as they headed down a hill

in either a wagon or a sled.

Watterson ended Calvin and Hobbes in 1995. Watterson was

known to dislike the deadlines, commercialization, and restraints of

syndicated comics, which most likely motivated his retirement. While

Watterson never permitted merchandising of his Calvin and Hobbes

characters, Calvin and Hobbes reprints remained in stores, and Calvin

images, though most likely unlicensed, continued to be displayed in

cars and trucks. Calvin and Hobbes collections include Something

under the Bed Is Drooling (1988), Yukon Ho! (1989), and The Calvin

and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book (1989).

Like Gary Larson of The Far Side, Watterson had a unique honor

bestowed on him by the scientific community. On one adventure,

Calvin and Hobbes explored Mars. When the Mars Explorer sent back

pictures of Mars, NASA scientists named two of the Mars rocks

Calvin and Hobbes.

—P. Andrew Miller

F

URTHER READING:

Holmen, Linda, and Mary Santella-Johnson. Teaching with Calvin

and Hobbes. Fargo, North Dakota, Playground Publishing, 1993.

Kuznets, Lois Rostow. When Toys Come Alive. New Haven, Con-

necticut, Yale University Press, 1994.

Watterson, Bill. Calvin and Hobbes. New York, Andrews and

McMeel, 1987.

Camacho, Héctor ‘‘Macho’’ (1962—)

In 1985, boxer Héctor Camacho, known for his flashy style and

flamboyant costuming as a ‘‘Macho Man’’ and ‘‘Puerto Rican

Superman,’’ became the first Puerto Rican to have won the World

Boxing Championship (WBC) and World Boxing Organization (WBO)

championships in the lightweight division. Born in Bayamón, Puerto

Rico, in 1962, Camacho won 40 of his first 41 fights culminating with

his victory over José Luis Ramos for the WBC lightweight champion-

ship. In 1987, Camacho moved up to the super lightweight division, in

which he fought only seven sluggish battles before retiring in 1994.

The two highlights of this latter career were his victory over World

Boxing Association (WBA) lightweight champion Ray ‘‘Boom Boom’’

Mancini in 1989 and his 1992 fight with Julio César Chávez for a $3

million payoff.

—Nicolás Kanellos

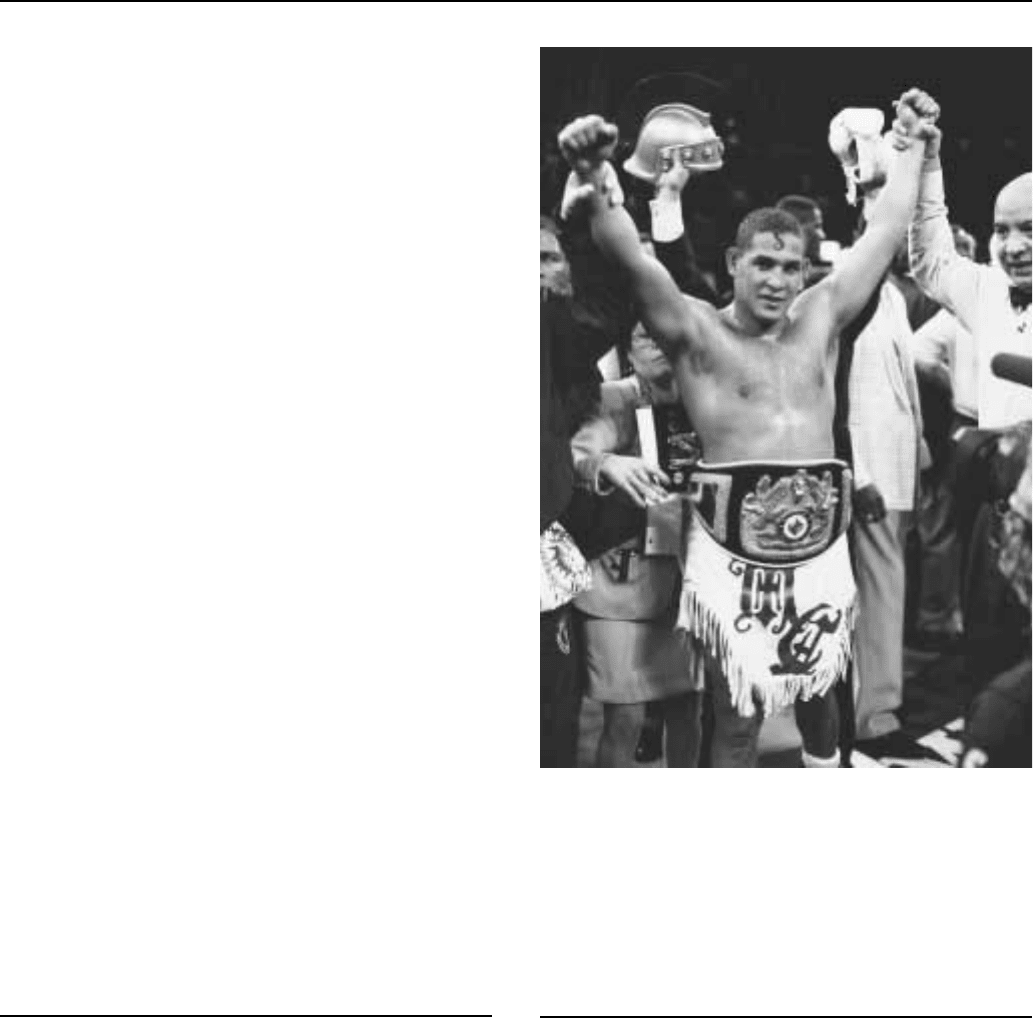

Héctor “Macho” Comacho

FURTHER READING:

Tardiff, Joseph T., and L. Mpho Mabunda, editors. Dictionary of

Hispanic Biography. Detroit, Gale, 1996.

Camelot

Camelot, a musical by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe

based on T.H. White’s version of the Arthurian romance The Once

and Future King, was one of the most successful Broadway musicals

of the 1960s. The original production starred Julie Andrews, Richard

Burton, and Robert Goulet. Songs included ‘‘I Wonder What the King

Is Doing Tonight,’’ ‘‘Camelot,’’ ‘‘How to Handle a Woman,’’

‘‘C’est Moi,’’ and ‘‘If Ever I Would Leave You.’’ The 1967 film

version featured Richard Harris, Vanessa Redgrave, and Franco

Nero. Camelot contemporized the era of King Arthur and made the

legend accessible and appealing to 20th-century audiences through

the use of 1960s popular music styles, a skillful libretto, and well-

known performers. The influence of Camelot extended well beyond

the musical theater. It became a symbol of the administration of

President John F. Kennedy, an era—like that of King Arthur—whose

days were cut tragically short. The Oxford History of the American

CAMPENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

415

People (1965) even ends with a quote from the show: ‘‘Don’t let it be

forgot that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that

was known as Camelot.’’

—William A. Everett

F

URTHER READING:

Citron, Stephen. The Wordsmiths: Oscar Hammerstein 2nd & Alan

Jay Lerner. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Everett, William A. ‘‘Images of Arthurian Britain in the American

Musical Theater: A Connecticut Yankee and Camelot.’’ Sonneck

Society Bulletin. Vol. 23, No. 3, 1997, 65, 70-72.

Lerner, Alan Jay. The Street Where I Live. New York, W.W.

Norton, 1970.

Camp

‘‘Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste; that there

exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste.’’ In her well known 1964

piece, Notes on Camp, Susan Sontag summarized the fundamental

paradox that occupies the heart of ‘‘camp,’’ a parodic attitude toward

taste and beauty which was at that time emerging as an increasingly

common feature of American popular culture. Avoiding the drawn-

out commentary and coherence of a serious essay format, Notes on

Camp dashes off a stream of anecdotal postures, each adding its own

touches to an outline of camp sensibility. ‘‘It’s embarrassing to be

solemn and treatise-like about Camp,’’ Sontag writes. ‘‘One runs the

risk of having produced a very inferior piece of Camp.’’ And she was

right. To take camp seriously is to miss the point. Camp, a taste of bad

taste which languishes between parody and self parody, doesn’t try to

succeed as a serious statement of taste, but stages its own failure as

taste by doing and overdoing itself. In this way, failure is camp’s

greatest triumph and to take it away through a serious analysis would,

for Sontag, be tantamount to an annihilation of the subject. In fact,

since camp’s self-parody leaves no durable statement of taste, it

should only be spoken of as a verb: ‘‘camping,’’ the act of subverting

a taste by exaggerating its pomp and artifice to the point of absurdity.

Writing in 1964, Sontag already had a short history of popular

camp to reflect upon. From the mid 1950s, a peculiar sense of the

beauty of bad taste had crept into American culture thorough the

pages of MAD magazine and the writings of Norman Mailer—a

parodic smirk that would creep across the face of counter culture of

the 1960s and ultimately etch itself deeply into the American cultural

outlook. By the mid 1960s, camp’s triumphs were many: the glib,

colorful, and disposable styles of Pop gave way to the non-conformity

of hippie camp, which in turn inspired 1970s glam-rock camp, the

biting camp of punk and the irony and retro of the 1980s and 1990s

camp, while throughout the inflections of gay and drag camp were

never far away. In each case, camp’s pattern is clear: camp camps

taste. Less a taste in itself, more an attitude toward taste in general,

camp’s failed seriousness exaggerates to absurdity the whole posture

of serious taste, it ‘‘dethrones seriousness,’’ and reveals the vanity

and folly that underlies every expression of taste. And camp’s failure

is contagious. By affirming style over substance, the artifice of taste

over the content of art, and by undermining one’s own posture of good

taste by exaggerating its vanity and affect, camp exposes the lie of

taste in general—without confronting it with a superior standard.

Sontag writes: ‘‘Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of

ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t

argue that the good is bad or the bad is good. What it does is to offer

for art (and life) a different—a supplementary—set of standards.’’

Free from seriousness, camp can be cruel or kind: at moments camp

offers a boundless carnival of generosity to anyone willing to don a

disguise and share in the pomp and pretense that is taste, while at other

moments camp’s grotesque vanity might fly into jealous rage at the

competitor, the campier than thou, that threatens to rain on the charade.

Sontag traces camp to its origins as a gay sensibility in the

writings of Oscar Wilde and Jean Genet, who sought to dethrone the

seriousness of Victorian literary convention and the tastes of the

French bourgeoisie. In America, camp largely emerged from the need

to dethrone the conformity and banality of the consumer culture of the

1950s. ‘‘Pop’’ styles sprang out of a reaction to the conformity

imposed by the mass-produced culture provided by a ‘‘society of

abundance,’’ which unconvincingly advocated the virtues and pleas-

ures of life in a world of consumer goods. By the 1960s, that promise

was less and less convincing, and the adornments of the suburban

home seemed sadly inadequate as stand-ins for human satisfaction.

The colorful, flamboyant and garish styles of ‘‘Pop’’ provided some

relief for an American middle class increasingly inundated with

‘‘serious’’ consumer tastes in which it had no trust. In Britain a group

of painters calling themselves The International Group (whose mem-

bers included Richard Hamilton, John McHale, and Magda Cordell)

set out to sing the praises of the new culture of plenty in a slightly off-

key refrain: Hamilton’s famous 1956 collage of a suburban living

room asks with a conspicuous sincerity, ‘‘Just What Is It That Makes

Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?’’ The piece lampoons

the optimism and complacency of the new domestic bliss, while

celebrating its artifice. Camping the Americanization of the 1950s,

British Pop spread quickly to the garrets of New York where Roy

Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol quickly picked up the

trick of praising the land of opulence with the tongue squarely in

the cheek.

‘‘Pop’’ resonated in the mainstream of American cultural life

with the first of what would be many terrifically successful British

Invasions. Dethroning the ‘‘good taste’’ of mass culture with stylish

overkill, pop clothing, decoration, and graphics were exaggerated,

colorful and garish, silly and trite. The fashions of Mary Quant, the

photography of David Bailey, and ultimately the music of the Rolling

Stones and the Beatles offered stylistic excess as the antidote to the

‘‘square’’ tastes of the older generation. The pop-psychedelic expres-

sions of later years would confirm the superiority of mockery over

taste. The fad Vogue dubbed ‘‘Youthquake’’ trumpeted the shallow

excessiveness of a youthful taste as an endorsement of style over

substance—a camping of mass culture. Commercial imagery, camped in

this way, shaped the counter culture of the 1960s, from the Beatles’

Sergeant Pepper album cover to Warhol’s soup cans to the garish

colors of psychedelic attire to the magazine clipping collages that

covered many a teenager’s bedroom walls: camping was at once

subversive, clever, and affirming of one’s taste for bad taste. One

image in particular expresses this camping of mass culture that was

the achievement of Pop: Twiggy, the slim and youthful British model

who took Madison Avenue by storm in 1967, was pictured in a New

Yorker article posing in Central Park, surrounded by children, all of

whom wore Twiggy masks, photographic representations of the face

of the model. Camping the artifice of mass stardom had become part

of stardom itself.

CAMPBELL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

416

It was, however, the camp of the drag queen that would ultimate-

ly triumph in the counter culture, and claim the camp legacy for the

next decade. As early as Warhol’s Factory days, where Manhattan

drag queens like Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn were featured

prominently in such films as Chelsea Girls (1966), drag had always

had a cozy relationship with the counter culture. The relationship

became closer after the Stonewall riots of 1969, when drag style

emerged as the motif that gave rock a disturbing and intriguing gender

ambiguity. By the early 1970s, rock became increasingly open to

camp inflections of drag: Mick Jagger developed a strutting, effemi-

nate stage presence; David Bowie, Elton John, and Alice Cooper

brought excess and artifice together with gender ambiguity that was

taken directly from lively drag scenes and the queens who populated

the 1970s gay scene. The raucous screenings of Jim Sharman’s 1974

Rocky Horror Picture Show and John Waters’ 1973 Pink Flamingos

remain an enduring rite of college frat life.

As the 1970s wore on, New Wave and Punk movements drew on

camp’s preoccupation with dethroning the seriousness of taste. Such

early punk acts as the New York Dolls sharpened the whimsy of

Sharman’s Dr. Frankenfurter character into a jarring sarcasm, less

playful and flamboyant, more the instrument of an outraged youth,

cornered by the boredom and banality of a co-opted counter-culture, a

valueless society and the diminished hopes of a job market plagued by

economic recession. Unlike the witticisms of Wilde and the flourish

of Marc Boland and other dandies of glam rock, Punk’s version of

camp was meant to sting the opponent with a hideous mockery of

consumer pleasure. The Sex Pistols’ Holiday in the Sun album begins

with a droning comment on low budget tourism: ‘‘cheap holiday in

other people’s misery,’’ while the B-52s’ manic celebration of the

faux leisure of consumerism chided the ear with shrill praises of

‘‘Rock Lobster’’ and ‘‘Girls of the U.S.A.’’ Punk camp, however,

would have to be de-clawed before it could achieve mainstream

influence, which ultimately happened in the early 1980s with the

invasion (again from Britain) of such campy ‘‘haircut’’ acts as Duran

Duran and Boy George’s Culture Club. The effect of punk camp on

American popular culture has yet to be fully understood, though it

seems clear that ironic distance (cleansed of punk’s snarl) became a

staple of the culture of the 1980s and 1990s. Retro (a preferred terrain

of camp, which finds easy pickings in tastes already rendered ‘‘bad’’

by the relentless march of consumer obsolescence) preoccupied the

1980s, where the awkward styles of the 1950s could be resurrected in

such films as Back to the Future, and every aging rock star from Paul

McCartney to Neil Young could cop a 50s greaser look in an effort to

appear somehow up to date, if only by appealing to the going mode

of obsolescence.

If irony and detachment had by the 1990s become defining

features of the new consumer attitude, the camping of America is

partly to blame, or credit. However, the 1990s also witnessed an

unprecedented mainstreaming of drag in a manner quite different

from that of the 1970s. In the 1990s, figures like Ru Paul and films

like Wigstock signaled the visibility of drag styles worn by the drag

queens themselves, not by straight rockstars taking a walk on the wild

side. That drag could metamorphose over twenty years from a

psychological aberration and criminal act to a haute media commodi-

ty testifies to the capacity of American culture to adjust to and absorb

precisely those things it fears most. In the camping of America, where

the abhorrent is redeemed, the drag queen fares well.

—Sam Binkley

F

URTHER READING:

Roen, Paul. High Camp: A Gay Guide to Camp and Cult Films. San

Francisco, Leyland Publications, 1994.

Ross, Andrew. ‘‘Uses of Camp.’’ In No Respect: Intellectuals and

Popular Culture. New York, Routledge, 1989.

Sontag, Susan. ‘‘Notes on Camp.’’ In Against Interpretation. New

York, Laurel, 1966.

Campbell, Glen (1936—)

After establishing himself as a reputable session guitarist for acts

including the Monkees and Elvis Presley in the early 1960s, Glen

Campbell came into his own as a country vocalist with a decided pop

twist. Delivering pieces by ace songwriters like Jimmy Webb, Camp-

bell’s hit singles of the mid-1960s—most notably ‘‘Witchita Line-

man’’ and ‘‘By the Time I Get To Phoenix’’—fused the steel guitar

sound of country with lilting string arrangements. By the early 1970s,

Campbell had placed a number of singles in the upper tiers of both pop

and country charts, and was even given the helm of his own popular

variety show, The Glen Campbell Good Time Hour, but after ‘‘South-

ern Nights,’’ his final number one hit, Campbell kept a relatively

low profile.

—Shaun Frentner

F

URTHER READING:

Campbell, Glen, with Tom Carter. Rhinestone Cowboy: An Autobiog-

raphy. New York, Villard, 1994.

Campbell, Naomi (1971—)

Discovered while shopping in 1985, British model Naomi Camp-

bell became an instant success in the United States, where she

metamorphosed from a sweet schoolgirl into a polished—and, many

would say, primadonna—professional. Her long dark hair, fey eyes,

and feline figure established her as the first and for a long time the

only black supermodel; her looks were distinctively African in origin

but appealed to conservative Caucasian consumers as well. Her 1994

novel about the fashion business, Swan, focused primarily on white

characters but made an impassioned argument in favor of widening

modeling’s ethnic base; she also recorded an album and starred in

other artists’ music videos. Guarding her stardom jealously, Camp-

bell sometimes refused to appear in fashion shows alongside other

black models, and she was known for making outrageous demands for

hotel rooms and entertainment. Campbell eventually had to face

accusations of abuse from modeling agencies and a former assistant.

—Susann Cokal

F

URTHER READING:

Campbell, Naomi. Swan. London, Heinemann, 1994.

Gross, Michael. Model: The Ugly Business of Beautiful Women. New

York, William Morrow & Company, 1995.

CAMPINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

417

Tresniowski, Alex. ‘‘Out of Fashion.’’ People. November 23,

1998, 132-40.

Camping

Humans tamed the first campfires over 500,000 years ago, and

the word ‘‘camp’’ itself comes from the Latin campus, or ‘‘level

field,’’ but recreational camping as a popular cultural practice did not

emerge in the United States until the end of the nineteenth century,

when large numbers of urban residents went ‘‘back to nature,’’

fleeing the pressures of industrialization and increased immigration

for the temporary pleasures of a primitive existence in the woods.

The camping movement began in earnest in the mid-nineteenth

century, when upper-class men from New York, Boston, and other

northeastern cities traveled to the Catskills, the Adirondacks, and the

White Mountains to hunt, fish, and find solace in the beauty and

sublimity of untrammeled nature. Encouraged by such books as

William H. H. Murray’s Adventures in the Wilderness; or, Camp-life

in the Adirondacks (1869), these men sought to improve their moral

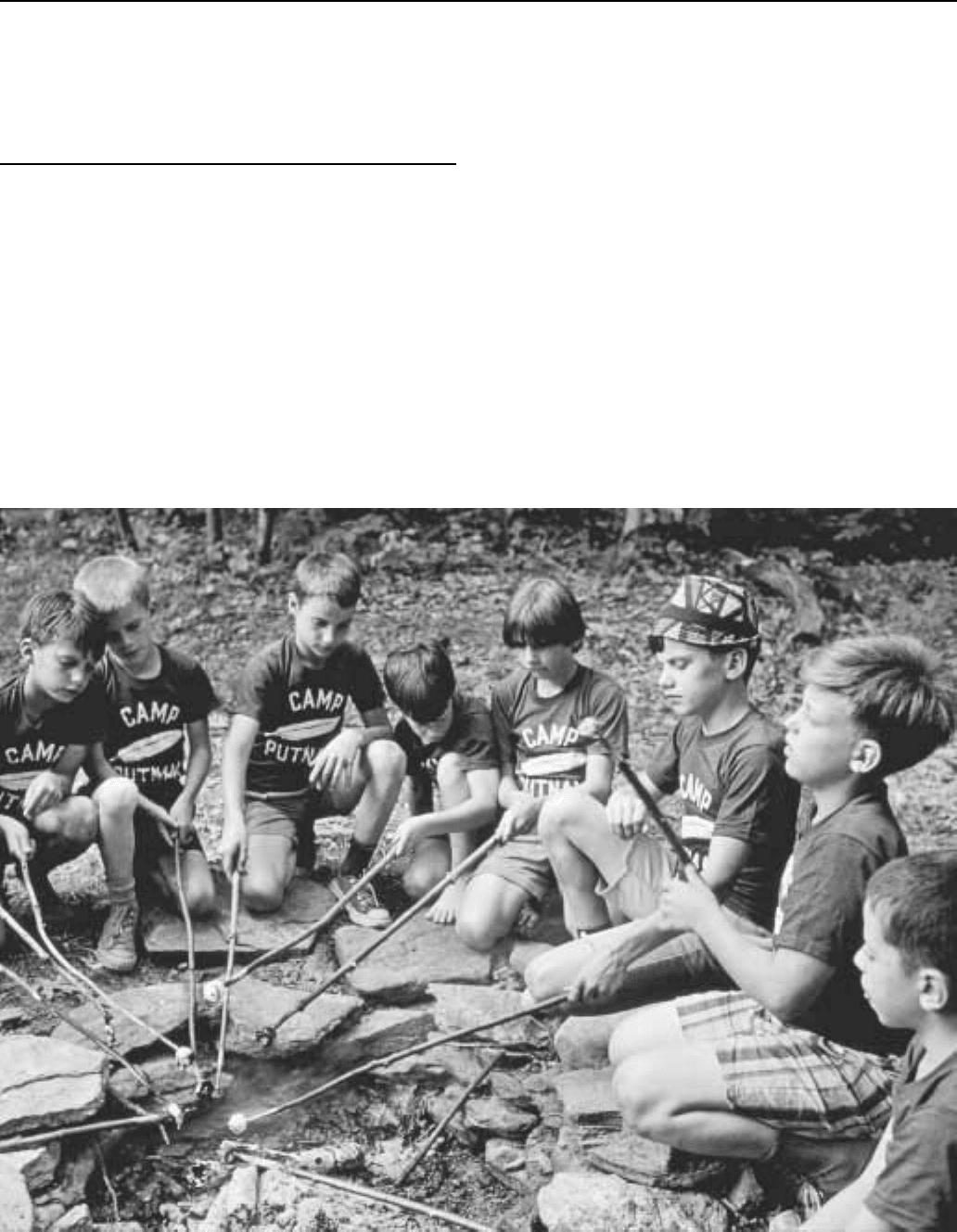

A group of boys at camp toasting marshmallows over an open fire.

and physical health and test their masculinity against the wilderness,

much as their working-class brethren had tested it on the battlefields

of the Civil War. They also set the tone of nostalgic nationalism that

would characterize camping throughout the twentieth century, identi-

fying themselves with idealized images of the pioneer frontiersmen as

rugged individualist and the American Indian as Noble Savage.

By the end of the nineteenth century, and especially after the

‘‘closing of the frontier’’ in 1890, camping had developed into an

established middle-class activity, one that relied as much on cities and

industries as it sought to flee them. Its increasing popularity could be

seen in the formation of outdoor clubs, such as the Boone and

Crockett Club (1887) and the Sierra Club (1892); the publication of

camp manuals, such as George W. Sears’s Woodcraft (1884) and

Horace Kephart’s Camping and Woodcraft (1906); and the appear-

ance of related periodicals, such as Forest and Stream (1873), Outing

(1882), and Recreation (1894). Easy access to remote areas was made

possible by the railroads, and the growth of the consumer culture—as

evidenced by the development of department stores, such as Mont-

gomery Ward (1872), and the mail-order business of Sears, Roebuck

(1895)—provided campers with the proper gear for their wilderness

voyages. At the same time, however, many campers supported the

CANCER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

418

conservation and preservation movements, which helped to establish

the first national parks and forests.

The same forces of urbanization and industrialization that influ-

enced the popularity of recreational camping among adults also

affected the development of organized camping for children and

young people. Although a long summer vacation made sense for a

rural, agricultural population, technological advancements, and the

expansion of the cities made this seasonal break from compulsory

education increasingly obsolete in the late nineteenth century. Never-

theless, many schools continued to close for the months of June, July,

and August, and parents, educators, and church leaders were forced to

look elsewhere for ways to keep children occupied during the hot

summer months. Camp provided the perfect solution.

The first organized camping trip in the United States is said to

have occurred in 1861, when Frederick William Gunn and his wife

supervised a two-week outing of the Gunnery School for Boys in

Washington, Connecticut, but the first privately operated camp did

not appear until 1876, when Joseph Trimble Rothrock opened a camp

to improve the health of young boys at North Mountain in Luzerne

County, Pennsylvania. The oldest continuously operating summer

camp in the United States—‘‘Camp Dudley,’’ located on Lake

Champlain—was founded in 1886 by Sumner F. Dudley, who had

originally established his camp on Orange Lake, near Newburgh,

New York. By 1910, the organized camping movement had grown

extensive enough to justify the founding of the American Camp-

ing Association, which by the 1950s boasted more than five

thousand members.

Classifiable as either day camps or residential camps, summer

camps have generally provided a mixture of education and recreation

in a group-living environment in the out-of-doors, and their propo-

nents have claimed that the camps build character, encourage health

and physical fitness, enhance social, psychological, and spiritual

growth, and foster an appreciation for the natural world. The majority

of camps have been run by nonprofit organizations, such as the Boy

and Girl Scouts, Camp Fire Girls, Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs, 4-H Clubs,

Salvation Army, YMCA, YWCA, YM-YWHA, and churches, syna-

gogues, and other religious groups. Others have been private camps

run by individuals and corporations, or public camps run by schools,

municipal park and recreation departments, and state and federal

agencies. Especially notable in the twentieth century has been the

advent of innumerable special-interest camps, such as Christian and

Jewish camps, sports camps, computer camps, language camps, space

camps, weight-loss camps, and camps for outdoor and arts education.

Recreational camping developed in parallel with organized

camping in the early twentieth century, influenced in part by the

popularity of such nature writers as Henry David Thoreau, John Muir,

and John Burroughs. Equally influential was the mass-production of

the automobile and the creation of the modern highway system, which

led to the development of motor camping and the formation of such

organizations as the American Automobile Association, the Recrea-

tional Vehicle Association, and the Tin Can Tourists of America. The

growth of camping reached a milestone in the 1920s, with camping

stories being written by Ernest Hemingway and Sinclair Lewis; new

products being developed by L. L. Bean and Sheldon Coleman

(whose portable gas stove appeared in 1923), and the first National

Conference on Outdoor Recreation being held in 1924.

The postwar suburbanization of the United States, combined

with advances in materials technology and packaging, helped to turn

camping into a mass cultural activity in the late twentieth century, one

whose popularity not only affected the management of natural areas

but also called into question its own reason for being. Nearly ten

million recreational vehicles, or RVs, were on the road in the late

1990s, forcing national parks to install more water, sewer, and power

lines and close less desirable tent-camping sites. Meanwhile, the

introduction of aluminum-frame tents in the 1950s, synthetic fabrics

in the 1960s, freeze-dried foods in the 1970s, chemical insect repel-

lents in the 1980s, and ultra-light camp stoves in the 1990s allowed

campers to penetrate further into the backcountry, where they often

risked disturbing ecologically sensitive areas. With the invention of

cellular telephones and global positioning satellites, however, many

campers have begun to wonder whether their days as primitive

recreators may in fact be numbered, and whether it will ever again be

possible to leave technology and civilization behind for the light of an

evening campfire and the silence of a beeperless world.

—Daniel J. Philippon

F

URTHER READING:

Belasco, Warren James. Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to

Motel, 1910-1945. 1979. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1997.

Eells, Eleanor. History of Organized Camping: The First 100 Years.

Martinsville, Indiana, American Camping Association, 1986.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman, ed. A Worthy Use of Summer: Jewish

Summer Camping in America. With Karen S. Mittelman. Intro.

Chaim Potok. Philadelphia, National Museum of American Jew-

ish History, 1993.

Kephart, Horace. Camping and Woodcraft: A Handbook for Vacation

Campers and Travelers in the Wilderness. Rev. ed. Intro. Jim

Casada. 1917. Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Kraus, Richard G., and Margaret M. Scanlin. Introduction to Camp

Counseling. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1983.

Schmitt, Peter J. Back to Nature: The Arcadian Myth in Urban

America. Foreword by John R. Stilgoe. 1969. Baltimore, Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1990.

Cancer

Cancer is not a single disease, but rather a monster with many

faces. Doctors and scientists have listed more than 200 varieties of

cancer, each having different degrees of mortality, different means of

prevention, different hopes for a cure. Carcinomas hit mucous mem-

branes or the skin, sarcomas attack the tissues under the skin, and

leukemia strikes at the marrow—and these are just a few varieties of

cancer. Cancers are all characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation

of cells under pre-existing tissues, producing abnormal growths. Yet

popular attitudes toward cancer have been less bothered with medical

distinctions than with providing a single characterization of the

disease, evoking a slow and painful process of decay that comes as a

sort of punishment for the patient. ‘‘Cancerphobia’’ is, as Susan

Sontag and James T. Patterson have shown, deeply rooted in

American culture.

Cancer is a very ancient disease, dating back to pre-historic

times. Archeological studies have allowed scientists to detect breast

cancer in an Egyptian mummy, while precise descriptions of different