Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHARLIE’S ANGELSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

479

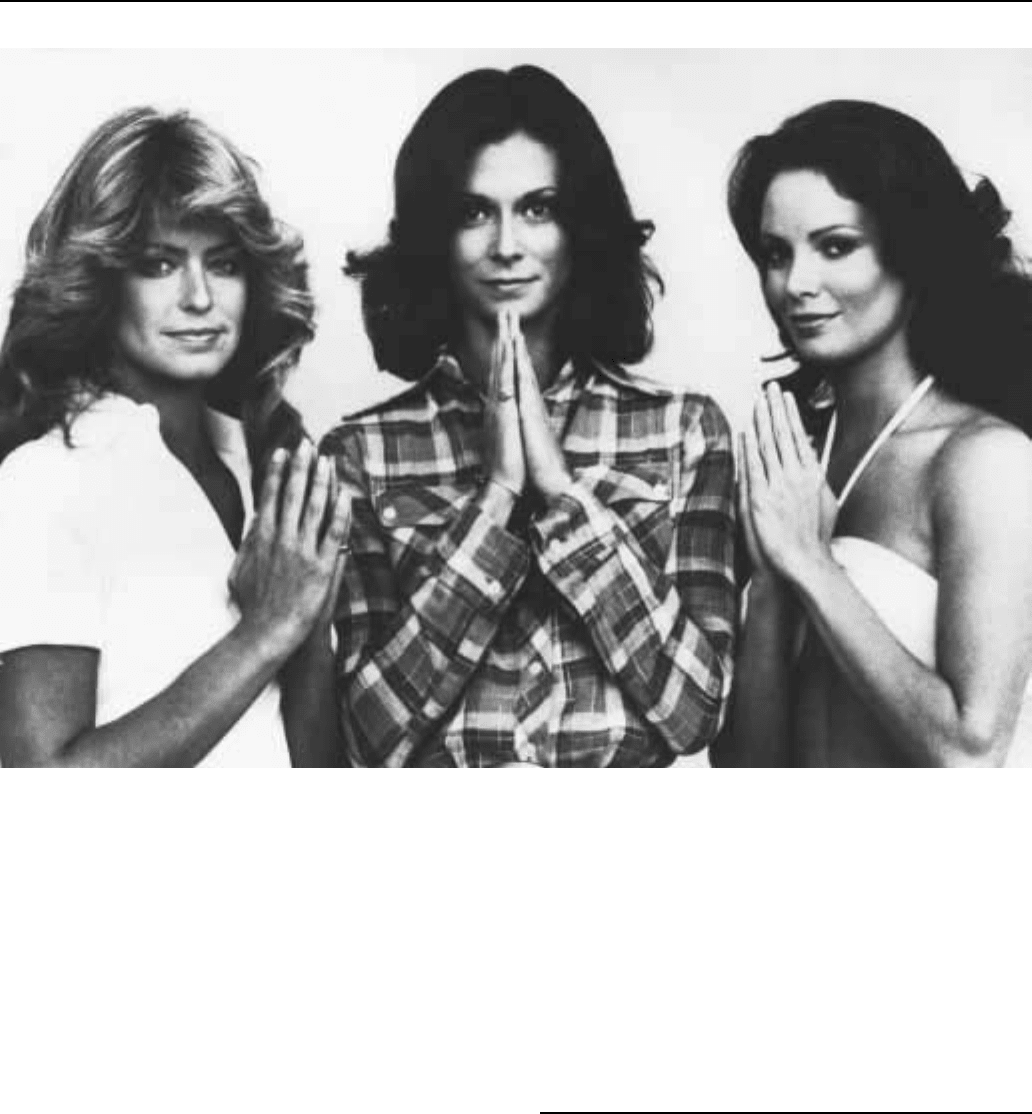

Charlie’s Angels: (from left) Farrah Fawcett-Majors, Kate Jackson, and Jaclyn Smith.

As Jim Harmon has pointed out in The Great Radio Comedians,

‘‘The humor (of Bergen and McCarthy) sprang from (an) inevitable

misunderstanding between a rather scholarly man and a high-school

near-dropout with native wit and precocious romantic interests. What

resulted was wildly comic verbal fencing, perfect for the sound-

oriented medium.... Exasperating to some adults, but we who were

children at the time loved it.’’ Not unlike Groucho Marx, Charlie

appealed to listeners of all ages because he could get away with saying

something naughty or insulting to parental and authority figures. With

such catch phrases as ‘‘Blow me down!,’’ Charlie endeared himself to

generations of listeners and viewers, and paved the way for many

successful ventriloquism acts that followed. Bergen’s skill as a

comedy writer was such that he purposefully let Charlie have all the

laughs. When asked once whether he ever felt any hostility toward

Charlie, Bergen replied, ‘‘Only when he says something I don’t

expect him to say.’’

In 1978, ten days after announcing his retirement, Edgar Bergen

died. In his will, the ventriloquist had donated Charlie to the Smithso-

nian. In addition to the memory of decades of laughter, Bergen also

bequeathed to the world of show business his daughter, actress/writer/

photographer Candice Bergen.

—Preston Neal Jones

F

URTHER READING:

Bergen, Candice. Knock Wood. Boston, G. K. Hall, 1984.

Bergen, Edgar. How to Become a Ventriloquist. New York, Grosset &

Dunlap, 1938.

Harmon, Jim. The Great Radio Comedians. Garden City, N.Y.,

Doubleday, 1970.

Charlie’s Angels

Despite its pretensions as a prime-time detective show featuring

three women as ‘‘private eyes,’’ Charlie’s Angels was primarily

about glamour and bare skin. This proved to be a winning combina-

tion for the ABC network from 1976 to 1981 when the show broke

into the top ten of the Nielson ratings in its first week and improved its

position with each subsequent airing. While this success was due, in

no small part, to the machinations of ABC’s programming genius

Fred Silverman, who put it up against two short-lived, male dominat-

ed adventure shows—Blue Knight and Quest—one cannot discount

the appeal of three pretty women to viewers of both sexes.

CHARM BRACELETS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

480

Yet, the program’s concessions to its female audience were slim.

Beyond the symbolic breakthrough of having three women perform-

ing in roles normally reserved for men, while paying attention to

fashions and hairstyles, most of the show was dedicated to keeping

male viewers in a state of titillation and expectation. While likening

Charlie to little more than a glorified ‘‘pimp,’’ feminist journalist

Judith Coburn commented in a 1976 article that Charlie’s Angels was

one of the most ‘‘misogynist’’ shows that the networks had ever

produced. ‘‘Supposedly about strong women, it perpetuates the

myth most damaging to women’s struggle to gain professional

equality: that women always use sex to get what they want, even on

the job.’’

Generally, the plots revolved around the three sexy female

detectives who have left the police department to work for an unseen

boss named Charlie (John Forsythe) who conveyed his assignments

by telephone and through an assistant named John Bosley (David

Doyle). Each weekly episode usually called for one of the three

women to appear in a bikini or shorts within the first few minutes of

the show to hook the male viewers. After that, most of the stories

would be set in exotic locations such as Las Vegas, Palm Springs, or

other areas within easy reach of Los Angeles to provide ample

opportunities for the ‘‘Angels’’ to strip down to bare essentials while

ostensibly staying within the confines of the shows’ minimal plots.

Yet, ironically, all of the sex was in the dialogue. While viewers

reveled in the sight of three gorgeous women in a variety of scanty

attire, they never saw them in bed. This might detract from their status

as consummate professionals in the detective business. According to

the show’s publicity, the angels were more than simply pretty faces,

sexy tummies, and cascading hair, they were martial arts experts, race

car drivers, and shrewd poker players. Of the initial cast, Sabrina

(Kate Jackson), was the multilingual, intellectual type; Jill Munroe

(Farrah Fawcett-Majors) the physical, action-oriented member, and

Kelly Garrett (Jaclyn Smith), the former showgirl, was the cool

experienced ‘‘been around’’ member of the team who provided calm

leadership under pressure.

The idea for the show originated with producers Aaron Spelling

and Leonard Goldberg, who had previously specialized in action

adventure shows normally dominated by the gritty realism of the

inner city. But these were dominated by male policemen and private

detectives. In an effort to compete with an upsurge of female

dominated action series such as Police Woman, The Bionic Woman,

andWonder Woman, Spelling and Goldberg decided to inject the

traditional private detective genre with a dose of feminine pulchritude

with three gorgeous women who not only solved crimes but looked

great doing it.

Although the show was initially intended to feature Kate Jack-

son, then the best known actress of the three, it was Farrah Fawcett-

Majors who became the most recognizable icon. Due to some

‘‘cheesecake’’ publicity photos, including a swimsuit poster that

quickly appeared on the bedroom walls of every thirteen-year-old boy

in America, and a mane of cascading blonde hair, Farrah quickly

became a fad, appearing on T-shirts and on toy shelves as Farrah dolls

swept the nation. She became caught up in the publicity and left the

show after the first season in hopes of capitalizing on her fame and

becoming a movie star. Spelling and Goldberg replaced her in 1977

with Cheryl Ladd as her younger sister Kris Munroe and the show

continued unimpeded.

—Sandra Garcia-Myers

F

URTHER READING:

Hano, Arnold. ‘‘They’re Not Always Perfect Angels.’’ TV Guide.

December 29, 1979, 19-23.

O’Hallaren, Bill. ‘‘Stop the Chase—It’s Time for My Comb-Out.’’

TV Guide. September 25, 1976, 25-30.

‘‘TV’s Superwomen.’’ Time. November 22, 1976, 67-71.

Charm Bracelets

While charms and amulets, trinkets and tokens to ward off evil,

were worn on the body in ancient Egyptian civilization and virtually

every other early culture, the twentieth-century charm is far removed

from such apotropaic forms. Rather, modern charms are often signs of

travel, place, and popular culture, suggesting sentiment and affinity

more than prophylaxis. Their peak came in the 1930s when silver or

base-metal charms could be accumulated over time and in hard times

constituted affordable jewelry. Bakelite and other new materials

could also make charms even less expensively. By the 1950s, charm

bracelets were chiefly associated with high-school girls and the

prospect of being able in high-school’s four years to fill all the links of

a bracelet with personal mementos. A 1985 fad for the plastic charm

bracelets of babies—letter blocks and toys—worn by adults for

infantilizing effect lasted less than a year.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Congram, Marjorie. Charms to Collect, Martinsville, New Jersey,

Dockwra Press, 1988.

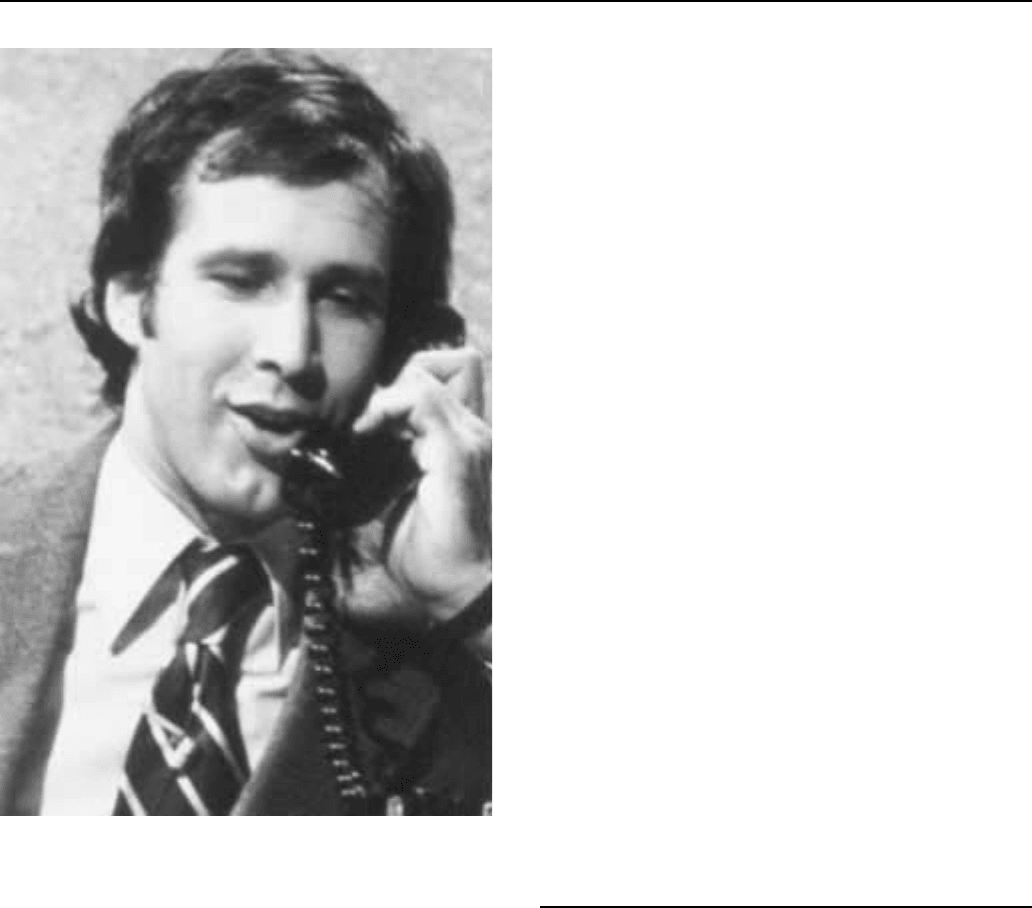

Chase, Chevy (1943—)

Comedian, writer, and actor Chevy Chase met instant critical

success and stardom on Saturday Night Live(SNL), first coming to

public attention as the anchor of the show’s ‘‘Weekend Update’’

news spoof with his resounding ‘‘Good evening. I’m Chevy Chase,

and you’re not!’’ His mastery of the pratfall, deadpan outrage, and

upper-class demeanor made him a standout from the rest of the SNL

cast, and only a year later, Chase was Hollywood-bound and starring

in movies that capitalized on his SNL persona. Chase appeared as a

guest host of SNL in February 1978, and the show received the

highest ratings in its history.

Born Cornelius Crane Chase (his paternal grandmother gave him

the nickname Chevy) on October 8, 1943, in New York City, Chase

earned a bachelor’s degree from Bard College in 1967. He worked on

a series of low-level projects, developing his talents as a comedy

performer and writer. In 1973 he appeared in the off-Broadway

National Lampoon’s Lemmings, a satire of the Woodstock festival, in

which he portrayed a rabid motorcycle gang member and a John

Denver type singing about a family freezing to death in the Rockies.

In 1974 he wrote and performed for National Lampoon’s White

House Tapes and the National Lampoon Radio Hour. Chase went to

Hollywood in 1975, where he wrote for Alan King (receiving the

Writers Guild of America Award for a network special) and The

Smothers Brothers television series.

CHAUTAUQUA INSTITUTIONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

481

Chevy Chase on Saturday Night Live.

While in a line for movie tickets, Chase met future SNL producer

Lorne Michaels, who was so entertained by Chase’s humor that he

offered him a job writing for the new show, which debuted October

18, 1975. In addition to writing, however, Chase moved in front of the

camera, sometimes with material he had written for ‘‘Weekend

Update’’ just minutes before. Besides this role, he most famously

appeared as President Gerald Ford. His impersonation focused on

pratfalls, and served to create an image of a clumsy Ford, which the

president himself enjoyed: Ford appeared in taped segments of one

episode of SNL declaring ‘‘I’m Gerald Ford, and you’re not.’’ Chase

won two Emmys—one for writing and one for performing—for his

SNL work, but his standout success on a show that was supposed to

rely on a repertory of actors led to strained relations with the equally

popular John Belushi, Michaels, and other colleagues, especially

since Chase was not being paid as a performer but as a writer. Chase

left SNL in October 1976 and, tempted by movie offers, moved back

to California.

In 1978, Chase’s first major movie, Foul Play, received mixed

reviews, but his name was enough to ensure that it was profitable. The

movies that followed, including Caddyshack and Oh Heavenly Dog

(both in 1980) also made some money, but Chase himself made

negative comments about their artistic quality. In 1983, returning to

his comedy roots, Chase starred as Clark Griswold, a role perfectly

suited to his deadpan humor, in National Lampoon’s Vacation. The

movie was a great success and has since been followed by three sequels.

About this time, the actor also was coping with substance-abuse

problems. Like many other early alumni of SNL, he was exposed to

drugs early in his career, but he also had become addicted to

painkillers for a degenerative-disk disease that had been triggered by

his comic falls. He was able to wean himself from drugs through the

Betty Ford clinic in the late 1980s. In the meantime, he continued to

star in movies such as Fletch (1985).

His career began to flag at the start of the 1990s. Chase was heard

to remark that he missed the danger of live television, so it came as no

surprise to those that knew him that he took a major risk in launching

The Chevy Chase Show, a late-night talk show which was one of

several efforts by comedians in 1993 to fill the void left by the

retirement of Johnny Carson. Like many of the others, it was soon

canceled. Since then, Chase has made a number of attempts to revive

his movie career. He made the fourth Vacation movie (Vegas Vaca-

tion) in 1997 and began work on a new Fletch movie in 1999. Many

critics, however, see him as just going through the motions, cashing in

on his name and characters before it is too late. The public, however,

still thinks of him as Chevy Chase, man of many falls and

few competitors.

—John J. Doherty

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Chase, Chevy.’’ Current Biography Yearbook. Edited by Charles

Moritz. New York, H. W. Wilson Co., 1979.

Hill, Doug, and Jeff Weingrad. Saturday Night: A Backstage History

of Saturday Night Live. New York, Beech Tree, 1986.

Murphy, Mary. ‘‘He’s Chevy Chase and They’re Not.’’ TV Guide.

August 28-September 3, 1993, 14-17.

The Chautauqua Institution

During its first eighty years, more famous men and women,

including American presidents, appeared under the auspices of the

Chautauqua Institution, located on the shore of Lake Chautauqua in

an obscure part of northwestern New York, than at any other place in

the country. Built in 1874, Chautauqua was headquarters for a

phenomenally successful late nineteenth-century religious and mass

education movement that satisfied a deep hunger throughout America

for culture and ‘‘innocent entertainment’’ at reduced prices.

Philosopher William James visited the site in 1899 and was

astonished by the degree to which its small-town values informed

nationwide programs. The institution reflected the inexhaustible

energies and interests of two founders, Lewis Miller, a wealthy

Akron, Ohio, manufacturer of farm machinery (and Thomas A.

Edison’s future father-in-law), and John Heyl Vincent, who at eight-

een had been licensed in Pennsylvania as a Methodist ‘‘exhorter and

preacher.’’ Both had grown up in rural America, and both were

especially knowledgeable about the tastes and yearnings of their

fellow citizens.

Long before James’s visit, Miller had helped finance revival

meetings in a hamlet near Lake Chautauqua, but attendance had

CHAVEZ ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

482

declined. While searching for a way to continue his vision of the

Lord’s work, Miller read some of Vincent’s writings, came to the

belief that financial salvation was attainable if some new purpose for

the site could be found, and contacted Vincent. Vincent disliked

razzle-dazzle evangelism but agreed that training young men and

women as Sunday school teachers could be the worthy purpose that

Miller sought.

A Sunday School Assembly was formed and enjoyed immediate

success. However, a looming problem was that as the school’s

enrollment steadily increased, so did concerns about chaperoning

students. Miller and Vincent feared possible scandals in sylvan

glades, unless idle time could be filled with regular and wholesome

educational and entertainment programs. To direct such activities,

they engaged William Rainey Harper, an Ohio-born educator, who

would later be John D. Rockefeller’s choice to serve as president of

the University of Chicago.

Like Miller and Vincent, Harper never opposed an idea because

it was new or unproven. Four years after the Sunday School Assembly

began operations the Chautauqua Literary Scientific Circle came into

being. One measure of its success was that within twenty years, ten

thousand reading circles, all of which took their lead from the

institution’s example, were operating throughout America. One fourth

were in villages of fewer than five hundred people, and Chautauqua

served them diligently, providing reading lists and other materials.

But innovations at Chautauqua did not stop with the training of

Sunday school teachers and reading circles. As early as 1883, it

chartered itself as a university and would remain one for twelve years,

until established universities began to offer summer courses. Some

three hundred ‘‘independent’’ or loosely affiliated similar institutions

used Chautauqua as a model without charge by the institution. As

early as 1885, a Chautauqua Assembly was held in Long Beach,

California, where rollers breaking on wide stretches of white sand and

bracing sea air further encouraged those who sought spiritual and

intellectual enlightenment during summer months.

For the benefit of those who could not afford travel to New York,

California, or independent Chautauquas, ‘‘tent chautauquas’’ came

into being. A tent would be pitched in a meadow and lecturers

engaged to inform locals on history, politics, and other subjects of

general as well as religious interest. Among the speakers, William

Jennings Bryan is said to have given fifty lectures in twenty-eight

days. The average price for admission was fifty cents, and no drinking

or smoking was allowed. A Methodist Dining Tent or Christian

Endeavor Ice Cream Tent supplied all refreshments.

Just after the turn of the century, Chautauqua was a ‘‘cultural

phenomenon with some of the sweep and force of a tidal wave,’’

wrote historian Russell Lynes. Women, who heretofore had little

chance to attend college, for the first time had an organization aware

of their educational needs that sought to begin opening up opportuni-

ties for them. By 1918, more than a million Americans would take

correspondence courses sponsored by the institution. A symphony

orchestra was created there, and in 1925 George Gershwin composed

his Concerto in F in a cabin near the Lake.

In the late 1920s, however, the advent of the automobile and the

mobility it offered the masses seemed to signal Chautauqua’s end.

Not only were untold millions abandoning stultifying small towns for

the temptations of metropolises, but those who stayed put had easy

access to cities for year-round education and entertainment.

In 1933 the institution went into receivership. Somehow it

refused to die. By the early 1970s, with buildings in disrepair and

attendance lagging, it appeared finally to be in its death throes—at

which point it renewed its existence. Richard Miller, a Milwaukee

resident and great-grandson of founder Lewis Miller, became chair-

man of the Chautauqua board. He began an aggressive fund-raising

campaign and built up financial resources until at the end of the

twentieth century the institution had $40 million and held pledges of

another $50 million from wealthy members.

More importantly, the Chautauqua Institution reached out for

new publics even as it preserved its willingness to continue a tradition

of serving people with insatiable curiosity about the world in which

they lived and a never-ending need for information. Although the tone

of its evangelical heritage remained, Catholics were welcome, about

20 percent of Chautauquans were Jews, and members of the rapidly

expanding black middle class were encouraged to join.

‘‘This is a time of growth,’’ declared eighty-five-year-old Alfreda

L. Irwin, the institution’s official historian, whose family had been

members for six generations, in 1998. ‘‘Chautauqua is very open and

would like to have all sorts of people come here and participate. I

think it will happen, just naturally.’’

—Milton Goldin

F

URTHER READING:

Harrison, Harry P. (as told to Karl Detzer). Culture under Canvas:

The Story of Tent Chautauqua. New York, Hastings House, 1958.

Lynes, Russell. The Taste-Makers. New York, Harper, 1954.

Smith, Dinitia. ‘‘A Utopia Awakens and Shakes Itself.’’ New York

Times. August 17, 1998, E1.

Chavez, Cesar (1927-1993)

Rising from the status of a migrant worker toiling in the

agricultural fields of Yuma, Arizona, to the leader of America’s first

successful farm worker’s union, Cesar Chavez was once described by

Robert F. Kennedy as ‘‘one of the heroic figures of our time.’’

Although by nature a meek and humble man known more for his

leadership abilities than his public speaking talents, Chavez appealed

to the conscience of America in the 1970s by convincing seventeen

million people to boycott the sale of table grapes for five consecutive

years. Chavez’s United Farm Workers Organizing Committee

(UFWOC) spearheaded the drive for economic and social justice for

Mexican and Mexican American farm workers. Lending their support

for this cause was a wide cross section of Americans, including

college students, politicians, priests, nuns, rabbis, protestant minis-

ters, unionists, and writers. By forming one of the first unions to fight

for the rights of Mexican Americans, Chavez became an important

symbol of the Chicano movement.

It would be a vast understatement to say that Chavez rose from

humble beginnings. Born in 1927, Chavez spent his early years on his

family’s small farm near Yuma. When his parents lost their land

during the Great Depression, they moved to California to work in the

fields as migrant workers. Young Chavez joined his parents to help

harvest carrots, cotton, and grapes under the searing California sun.

The Chavez family led a nomadic life, moving so often in search of

migrant work that Cesar attended more than thirty elementary schools,

many of which were segregated. By seventh grade, Cesar dropped out

of school to work in the fields full time.

CHAVISENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

483

Following service in the U.S. Navy during World War II,

Chavez moved to Delano, California, with his wife Helen Fabela. It

was in Delano that Chavez made the decision to take an active role in

improving the dire working conditions of migrant workers. In 1952,

Chavez became a member of the Community Service Organization,

which at the time was organizing Mexican Americans into a coalition

designed to confront discrimination in American society. Chavez’s

job was to register Mexican Americans in San Jose to vote, as well as

serve as their liaison to immigration officials, welfare boards, and

the police.

It was in the early 1960s, however, that Chavez began working

exclusively to ameliorate the economic and labor exploitation of

Mexican American farm workers. He formed the Farm Workers

Association in 1962, which later became the National Farm Workers

Association (NFWA). By 1965, 1,700 families had joined the NFWA,

and during that same year the organization had convinced two major

California growers to raise the wages of migrant workers. After the

NFWA merged with an organization of Filipino workers to form the

United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC), the UFWOC

in 1966 launched a campaign picketing grape growers in Delano who

paid low wages. This campaign, which nationally became known as

La Huelga (The Strike), proved to be the defining moment in

Chavez’s work as a labor activist. The highly publicized five-year

strike against grape growers in the San Joaquin, Imperial, and

Coachella valleys raised America’s consciousness about the condi-

tions of migrant workers and transformed Chavez into a national

symbol of civil disobedience. By holding hunger strikes, marches,

and sit-ins, as well as having himself arrested in order to gain attention

to his cause, Chavez led a boycott that cost California grape growers

millions of dollars. In 1970, the growers agreed to grant rights to

migrant workers and raised their minimum wage.

La Huelga was the first of many successful boycotts that Chavez

organized on behalf of grape and lettuce pickers, and he also fought

for the civil rights of African Americans, women, gays, and lesbians.

Although membership in the UFWOC eventually waned, Chavez

remained a beloved figure in the Mexican American community and

nationally represented the quest for fairness and equality for all

people. When Chavez died on April 23, 1993, at the age of sixty-six,

expressions of bereavement were received from a host of national and

international leaders, and a front-page obituary was published in the

New York Times.

—Dennis Russell

F

URTHER READING:

Dunne, John Gregory. Delano: The Story of the California Grape

Strike. New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967.

Ferriss, Susan, and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar

Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement. New York, Harcourt

Brace, 1997.

Levy, Jacques. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. New

York, W. W. Norton, 1975.

London, Joan, and Henry Anderson. So Shall Ye Reap: The Story of

Cesar Chavez and the Farm Workers’ Movement. New York,

Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1970.

Matthiessen, Peter. Sal Si Puedes: Cesar Chavez and the New

American Revolution. New York, Dell Publishing Co., 1969.

Taylor, Ronald B. Chavez and the Farm Workers. Boston, Beacon

Press, 1975.

Chavis, Boozoo (1930—)

As the leading exponent of a unique musical tradition known as

zydeco, Boozoo Chavis is a genuine artist who is inextricably

enveloped within the regional landscapes of his culture. Lake Charles,

Louisiana, sits at the western apex of a roughly triangular area of

south Louisiana that is home to the black French-speaking population

known as Creoles. Here, among the horse pastures and the patchwork

fields of rice and sweet potatoes, Boozoo Chavis learned to play ‘‘la-

la music’’ on the accordion for the rural house dances that formed the

centerpiece of Creole social life. When the urbanized sounds of

rhythm and blues caught on among local blacks, it was Chavis who

first successfully blended traditional la-la songs with a more contem-

porary bluesy sound and with lyrics sung in English. In 1954 he

recorded the now classic ‘‘Paper in My Shoe,’’ which told of poverty

but with a beat that let you deal with it. Along with Clifton Chenier

who recorded ‘‘Ay Tete Fee’’ the following year, Boozoo Chavis is a

true pioneer of zydeco music.

In an unfortunate turn of events, Chavis felt he did not receive

what was his due from making that early record, and left off pursuing

music as an avocation, turning instead to raising race horses at ‘‘Dog

Hill,’’ his farm just outside Lake Charles. Though he continued to

play for local parties and traditional Creole gatherings such as Trail

Rides, he did not begin playing commercially again until 1984. Since

coming out of semi-retirement he has not wasted any time, however,

and has recorded some seven albums loaded with pure gems. Hey Do

Right! is titled after the nickname for his daughter Margaret.

Wilson Anthony Chavis was born October 23, 1930 some 60

miles east of the Lake Charles area where he would grow up. He does

not recall where his peculiar nickname came from, but it is a moniker

widely recognized among legions of zydeco fans today—caps and t-

shirts in south Louisiana proclaim in bright letters: ‘‘Boozoo, that’s

who!’’ Even as he approaches his seventieth birthday, Chavis still

knows how to work a crowd. Whether it is in the cavernous recesses

of a legendary local club like Richard’s in Lawtell or Slim’s Y-Ki-Ki

in Opelousas, or commanding an outdoor stage at the congested New

Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Boozoo performs like the sea-

soned professional he has become, with great vigor and joie de vivre.

He characteristically runs through a long sequence of tunes one after

another, without even taking a break. His trademark clear plastic

apron keeps the sweat from damaging the bellows of his diatonic

button accordion, which he still prefers over the piano key instrument

that is more common among zydeco artists of his generation. Every

Labor Day, Boozoo hosts a picnic at Dog Hill which is open to the

public, thereby continuing the tradition of rural house dances where

zydeco began. Numerous bands contribute to the day’s entertainment,

and Boozoo always plays last, making the final definitive statement of

what this music is all about.

Afraid of flying, he mainly limits touring to places within easy

driving distance of Lake Charles, to all points between New Orleans

and Houston, the extremities of zydeco’s heartland. But with increas-

ing recognition of his talent and position as leading exponent of

zydeco, Chavis has begun to travel more widely, heading for locations

like New York, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, or Seattle. No

CHAYEFSKY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

484

matter where he plays, Boozoo has never strayed from the recognition

that zydeco is first and foremost dance music. His songs include many

of the old French waltzes and two-steps from earlier times, but are

always spiced up a bit in his inimitable fashion. In a recently

published book, zydeco observer Michael Tisserand characterized

Boozoo’s playing as a ‘‘punchier, more percussive style.’’ Thematically,

Chavis stays close to home, writing songs about his family, friends,

farm, and beloved race horses that sport names such as ‘‘Camel’’ and

‘‘Motor Dude.’’

In the face of ever more urban and homogenizing influences on

zydeco, Boozoo Chavis remains rooted in the music’s rural traditions.

He is just as likely to be fixing up the barn or working with his horses

as playing at a dance or a concert. While a half-serious, half in jest

controversy has simmered over the years regarding who should

follow the reign of Clifton Chenier as the King of Zydeco, most

cognoscenti agree that of all the leading contenders for the crown,

Boozoo Chavis is most deserving of the accolade. He is the perennial

favorite at the Zydeco Festival in Plaisance, Louisiana, where he often

waits in the shade of the towering live oaks to greet his many fans and

sign autographs. His music, like the person that he is, is the real article.

—Robert Kuhlken

F

URTHER READING:

Broven, John. South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous.

Gretna, Louisiana, Pelican Publishing, 1983.

Nyhan, Patricia, et al. Let the Good Times Roll! A Guide to Cajun &

Zydeco Music. Portland, Maine, Upbeat Books, 1997.

Tisserand, Michael. The Kingdom of Zydeco. New York, Arcade

Publishing, 1998.

Chayefsky, Paddy (1923-1981)

Distinguished playwright, novelist, and screenwriter Paddy (born

Sidney) Chayefsky was a major force in the flowering of post-World

War II television drama, sympathetically chronicling the lives and

problems of ordinary people. His most famous piece of this period is

Marty, about the love affair between two homely people, which

became an Oscar-winning film in 1955. Bronx-born and college

educated, he attempted a career as a stand-up comic before military

service, and began writing when wounded out of the army. The most

acclaimed of his Broadway plays is The Tenth Man (1959), drawing

on Jewish mythology, but he found his wider audience through

Hollywood, notably with original screenplays for The Hospital (1971)

and Network (1976), both of which won him Academy Awards and

revealed that he had broadened his scope into angry satire. He

controversially withdrew his name from the 1980 film of his novel

Altered States (1978), which he had adapted himself, and died a

year later.

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Considine, Shaun. Mad as Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy

Chayefsky. New York, Random House, 1994.

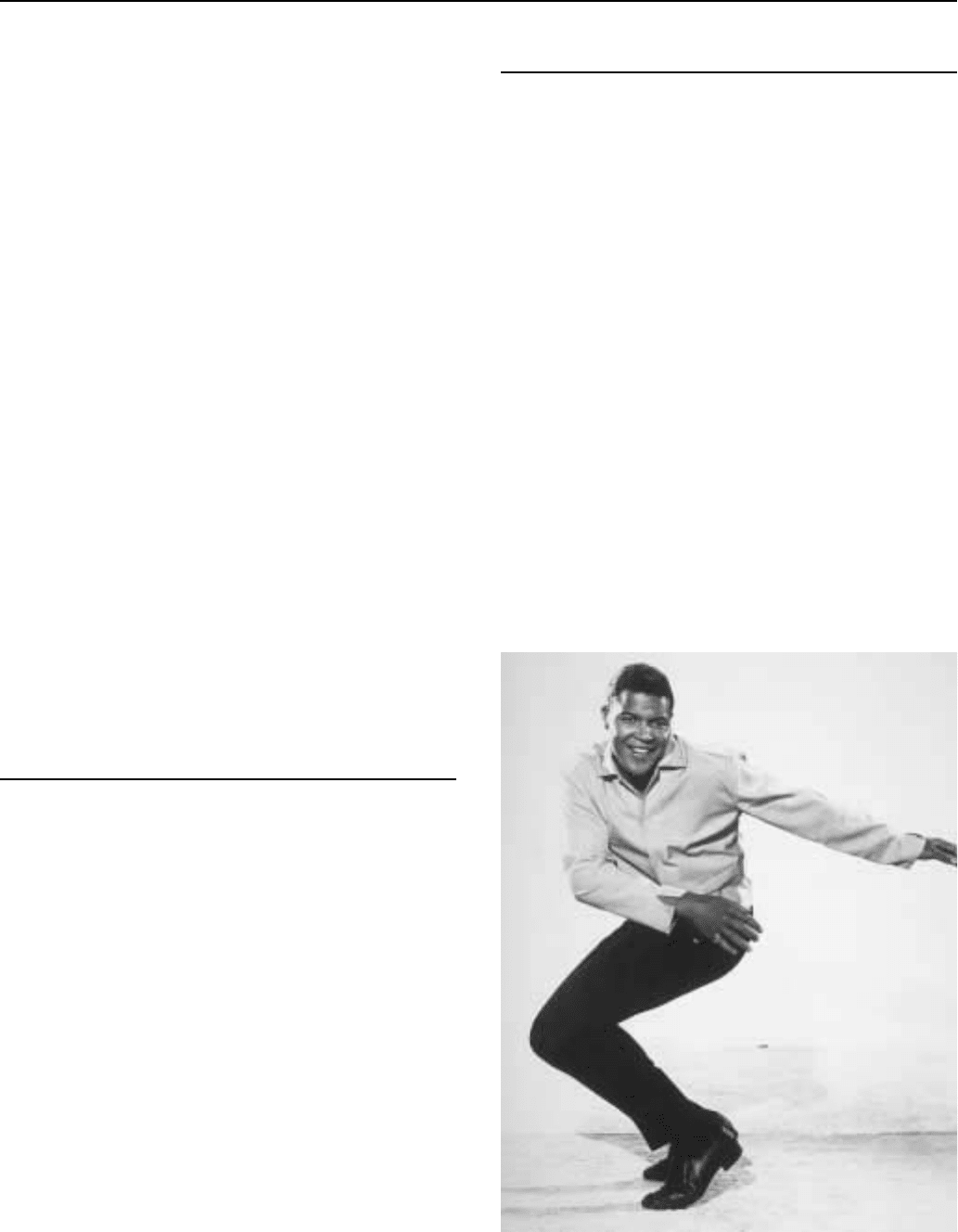

Checker, Chubby (1941—)

One of several popular male vocalists to emerge from the

Philadelphia rock ’n’ roll scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s,

Chubby Checker was the chief beneficiary of the fervor created by the

dance known as the Twist.

Checker was born Ernest Evans on October 3, 1941 in Spring

Gully, South Carolina, the child of poor tobacco farmers. At the age of

nine he moved to Philadelphia and eventually began working at a

neighborhood produce market where he acquired his famous nick-

name ‘‘Chubby’’ from his employer. Evans’ big break, however,

came at age 16 while working at a local poultry market. Proprietor

Henry Colt overheard Evans singing a familiar tune as he went about

his work. Colt was impressed with Evans’ talent and referred him to a

songwriter friend named Cal Mann who was, at that time, working

with Dick Clark.

Dick Clark and his American Bandstand had a lot to do with the

popularity of many Philadelphian singers who frequently appeared on

the program. Frankie Avalon, Bobby Rydell, Fabian, and Checker

were among the teen idols who careers took off after they gained

exposure to millions of American teenagers via television. Checker

was one of very few black teen idols of that period, however. In his

case, even his stage name derived from contact with Dick Clark. Clark

and his wife were looking for someone to impersonate Fats Domino

for an upcoming album. Hoping to give Evans’ career a boost, Clark’s

wife is said to have dubbed the young performer ‘‘Chubby Checker’’

because the name sounded like Fats Domino.

Chubby Checker

CHEECH AND CHONGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

485

The song entitled ‘‘The Twist’’ was originally released as the

flip side of a 45 rpm single by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, a

popular R&B singing group. Checker released ‘‘The Twist’’ as an A-

side on the Parkway label in August 1960, aggressively promoting the

record and the dance in personal appearances and on television.

Numerous Chubby Checker performances on programs like the

Philadelphia-based American Bandstand helped fuel both the Twist

Craze and Checker’s career.

Chubby Checker’s recording of ‘‘The Twist’’ went to #1 on the

Billboard Top 40 charts in mid-September, 1960. Eager to capitalize

on the success of that record, Checker released several other Twist-

related singles such as ‘‘Let’s Twist Again,’’ ‘‘Twist It Up,’’ and

‘‘Slow Twistin’.’’ In fact, almost all of his records were dance tunes,

such as the #1 hit ‘‘Pony Time,’’ ‘‘The Hucklebuck,’’ ‘‘The Fly,’’

and the #2 hit ‘‘Limbo Rock.’’

Several films were produced in an attempt to cash in on the

popularity of the Twist, and Chubby Checker was the star of two of

them. Alan Freed’s Rock around the Clock and Don’t Knock the Rock

were the first rock ’n’ roll exploitation films ever made, back in 1956;

in 1961 Chubby Checker starred in Twist around the Clock and Don’t

Knock the Twist, remakes of the Freed films made after only five

years had passed. Checker also went on to appear in other movies

such as Teenage Millionaire.

Perhaps as a result of the Twist movies being released in the

second half of 1961, the Twist craze resurfaced and Checker’s version

of ‘‘The Twist’’ was re-released by Parkway. The record was even

more successful the second time around, and ‘‘The Twist’’ was the

first #1 record of 1962. This is the only case during the rock ’n’ roll era

of the same record earning #1 on the Top 40 on two different occasions.

Four months later, in May 1962, Chubby Checker was awarded a

Grammy for best rock and roll recording of 1961, ostensibly for

‘‘Let’s Twist Again.’’ The latter was a moderate (#8) hit in 1961, but

in no sense the best rock ’n’ roll song of the year. Checker’s

triumphant re-release of ‘‘The Twist’’ did set a new record, but that

achievement took place in 1962, and technically the song was not

eligible for a 1961 Grammy.

Chubby Checker continued to release singles and albums of rock

and roll, primarily dance music. Although he had a few more hits,

such as ‘‘Limbo Rock’’ in 1962, no subsequent dances were ever as

good to Checker as the Twist had been. By the end of 1965 he had

placed 22 songs on the Top 40, including seven Top Ten hits, but his

best period was over by the end of 1962.

Since the mid-1970s Checker has benefitted from another trend,

oldies nostalgia. Along with many other former teen idols, Checker

has seen a resurgence of his career at state fairs and on oldies tours,

playing the old songs again for a multi-generational audience.

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Australian Fan Site of Chubby Checker.’’ http://www.ozemail.

com.au/~facerg/chubby.htm. February 1999.

Morrison, Tonya Parker. ‘‘Chubby Checker: ’The Wheel that Rock

Rolls On,’’’ American Press, 30 October 1998.

Nite, Norm N. Rock On Almanac. 2nd edition. New York,

HarperPerennial, 1992.

Stambler, Irwin. The Encyclopedia of Pop, Rock and Soul. Revised

edition. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. 6th edition. New

York, Billboard Books, 1996.

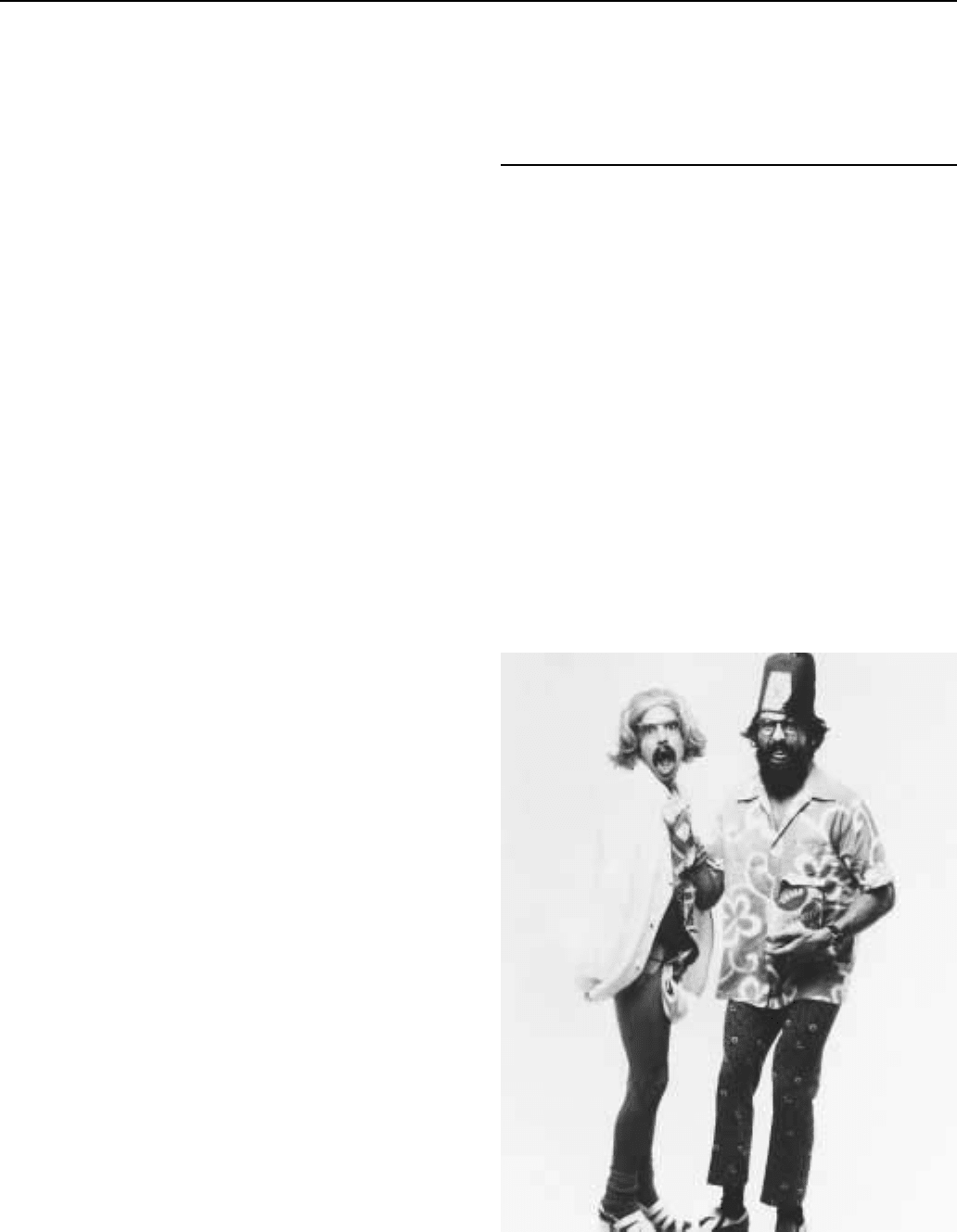

Cheech and Chong

Cheech and Chong were a comedy team of the early 1970s that

opened for rock bands, recorded a series of popular comedy albums,

performed on the college circuit, and appeared in their own movies.

Their comedy routines consisted largely of ‘‘doper jokes,’’ reflecting

the drug culture and scatological humor of the 1960s. Richard

‘‘Cheech’’ Marin (1946—) and Tommy Chong (1938—) met in 1968

in Vancouver, British Columbia, where Cheech had fled to avoid the

U.S. draft during the Vietnam War. Together they co-founded an

improv group called City Works, and performed in a nightclub owned

by Chong’s brother. By 1970 they were known as Cheech and Chong,

and were performing in nightclubs in Toronto and Los Angeles.

Canadian-born Tommy Chong, half Chinese and half Scottish-

Irish, was playing the guitar in a band called Bobby Taylor and the

Vancouvers when he met Cheech, who started out singing with the

band. Cheech, born of Mexican parents in South Central Los Angeles,

grew up in Granada Hills, near the San Fernando Valley. The duo

recorded several successful comedy albums in the early 1970s. In

1971, Cheech and Chong was nominated for a Grammy for Best

Comedy Recording, and their 1972 album Big Bambu retained the

record of being the largest-selling comedy recording for many years.

Los Cochinos won the Grammy for Best Comedy Recording in 1973.

Cheech Marin (left) and Tommy Chong

CHEERLEADING ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

486

Their humor, although very vulgar at times, was entertaining, with

Cheech playing a jaunty marijuana smoking dopehead, and Chong

playing a burned out, laid back musician.

Their successful movies of the late 1970s and early 1980s

became doper cult classics. Up in Smoke was released in 1978,

Cheech & Chong’s Next Movie in 1980, and Cheech & Chong’s Nice

Dreams in 1981. In these three movies they play simple-minded pot

heads, or left over hippies, but their comic teamwork has been

compared to Laurel and Hardy. The screenplays were written by both

Cheech and Chong, with the directing done primarily by Chong. Their

last films together were Things Are Tough All Over (1982), in which

they both play dual roles; Still Smokin’ (1983); The Corsican Brothers

(1984), in which they go ‘‘straight’’; and Cheech and Chong Get

Out of My Room, directed by Cheech in 1985 for the cable

channel Showtime.

The pair split up in 1985, and from there Tommy Chong’s career

fizzled. He starred in the 1990 film Far Out Man, which bombed, and

he tried stand-up comedy in 1991 without much success. Cheech

Marin, on the other hand, went on to a successful career as a director

and actor in several films and television shows. His film Born in East

L.A. (1987) has become a classic among Mexican Americans and is

often included in academic classes of Chicano Studies. In the 1990s

he received small supporting roles in several films, including a well-

received part in the hit Tin Cup, starring Kevin Costner, and played

the television role of Joe Dominquez in Nash Bridges.

—Rafaela Castro

F

URTHER READING:

Chong, Thomas, and Cheech Marin. Cheech and Chong’s Next

Movie. New York, Jove Publicatons, 1980.

Goldberg, Robert. ‘‘From Drugs to Duels: Cheech and Chong Go

Straight’’. Wall Street Journal. July 24, 1984.

Menard, Valerie. ‘‘Cheech Enjoys Second Career in TV.’’ Hispanic.

Vol. 9, No. 9, 1998, 12-14.

Mills, David. ‘‘Tommy Chong: Reefer Sadness.’’ Washington Post.

June 15, 1991, C1.

Cheerleading

Few archetypes so exemplify every stereotype of women in

modern culture as that of the cheerleader. An uneasy juxtaposition of

clean-cut athlete, ultra-feminine bubble-headed socialite, skilled dancer,

and buxom slut, the cheerleader is at the same time admired and

ridiculed, lusted after and legitimized by everyone from junior high

school girls to male sports fans. Though cheerleading began as an all-

male domain, and there are still male cheerleaders, it is for girls that

the role of cheerleader is a rite of passage, whether to be coveted or

scorned. Public figures as widely diverse as Gloria Steinem, John

Connally, and Paula Abdul spent part of their early years urging the

crowd to cheer for their athletic team.

Cheerleading as we know it began in November 1898 at a

University of Minnesota football game, when an enthusiastic student

named Johnny Campbell jumped up to yell:

Rah, Rah, Rah

Sku-u-mah

Hoorah, hoorah

Varsity, varsity

Minn-e-so-ta!

The idea caught on, and in the early 1900s at Texas A&M,

freshmen, who were not allowed to bring dates to athletic events,

styled themselves as yell leaders, with special sweaters and mega-

phones. They became so popular, especially with women, that soon

the juniors and seniors took the role away from the freshmen.

Only men took on the highly visible role of cheerleading until

after World War II, when women began to form cheerleading squads,

wearing demure uniforms with skirts that fell well below the knee. In

the late 1940s, the president of Kilgore College in Texas had the idea

of creating an attractive female dancing and cheering squad as a tactic

to keep students from going to the parking lot to drink during half

time. He hired a choreographer, commissioned flashy costumes, and

the idea of cheerleading as a sort of sexy show-biz entertainment took

off. By the 1990s, there were over three million cheerleaders nation-

wide, almost all of them female.

Cheerleading means different things on the different levels it is

practiced. In junior high, high school, and college, cheerleading is

very much a social construct. Cheerleading tryouts appeal to girls for

many reasons. Some seek the prestige and social status afforded those

who make the cut. These chosen few are admired by the boys and

envied by the girls as they represent their school at games and hobnob

with the boys’ elite—the athletic teams. Those who are rejected after

tryouts often experience deep humiliation. Of course there are many

who reject the school status hierarchies and who view the cheerlead-

ers as shallow snobs rather than social successes. Another way to

view cheerleaders is as strong athletes who seek recognition in one of

the only areas acceptable for females. In fact, in many schools, prior

to the Title IX laws of the 1970s, there were no athletic teams for girls,

and cheerleading was the only outlet where girls could demonstrate

athletic skill.

Many supporters of cheerleading stress the athletic side of

cheerleading and the strength required to perform the jumps and

gymnastic feats that accompany cheers. There are local and national

cheerleading competitions, where squads compete and are judged on

creativity, execution, degree of difficulty, and overall performance.

Over the years, cheerleading has developed from simple gestures and

jumps to difficult gymnastic stunts and complex dance routines. As

the athletic skill required to become a cheerleader has increased, so

has the number of cheerleading-related injuries. In 1986, the reputa-

tion of cheerleading suffered when two cheerleaders in different

schools were involved in major accidents within a week. A young

woman was killed and a young man paralyzed while practicing their

cheerleading stunts. A Consumer Product Safety Commission study

in 1990 found 12,405 emergency room injuries that year were

related to cheerleading, prompting parental demands for greater

safety precautions.

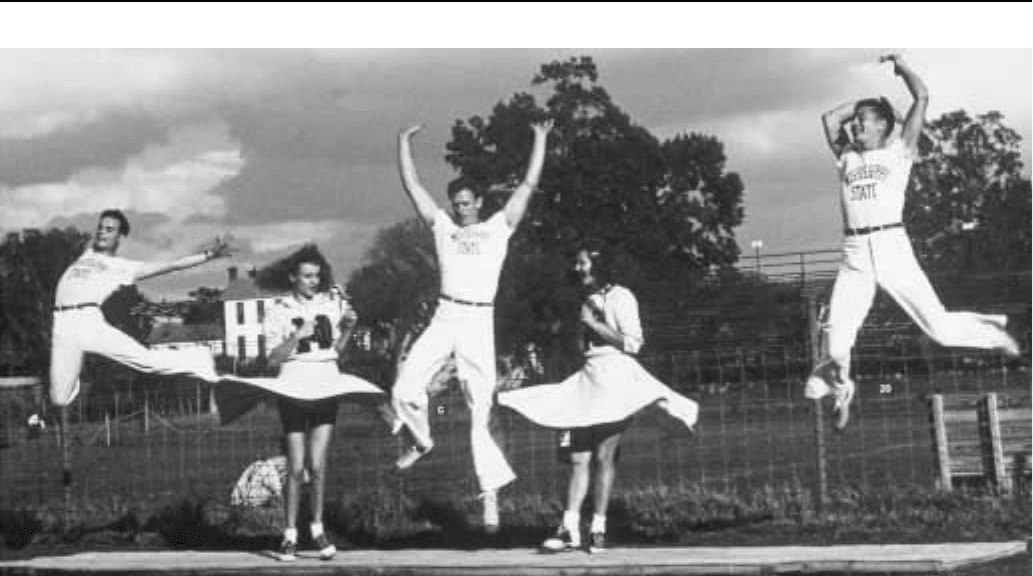

Another sort of cheerleading is found in professional sports.

While fitting a standard mold of attractiveness is one of the primary

requisites of any sort of cheerleading, the professional squads have

taken it to extremes. Tryouts for squads like the Dallas Cowboy

Cheerleaders, the New Orleans Saints’ Saintsations, and the Buffalo

Bills’ Buffalo Jills, seem almost like auditions for a Broadway play,

with hundreds of flamboyantly made-up dancers and performers

competing for a few openings. The cheerleaders perform for exposure

and love of their team rather than money. In an industry where the

CHEERLEADINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

487

A group of cheerleaders from Mississippi State University.

athletes might earn millions, most cheerleaders are paid only ten to

twenty-five dollars a game. Some are able to acquire contracts for

local advertising to supplement their income, and some hope to go on

to show business careers, but for many, just as in high school, it is the

admiration of the crowd and the identification with the team that is

the payoff.

It is in the professional arena that the risqué side of cheerleading

has received the most publicity. Because cheerleaders are almost

always chosen for standard good looks and shapely bodies in addition

to whatever skills may be required, even in high schools, rumors of

immorality circulate. In the professional squads, where outfits are

often skimpy and the routines flirtatious, the rumors are even more

graphic. Though most squads advertise a high moral standard, the

stereotype of the sexpot cheerleader has been hard to defeat. Movies

such as the XXX rated Debbie Does Dallas contribute to this, as did

the 1979 Playboy Magazine spread featuring nude photos of a

fictional cheerleading squad called the Texas Cowgirls.

Cheerleading has also grown into a big business. In the 1950s, a

former Texas high school cheerleader named James Herkimer (he

developed a cheerleading jump called the ‘‘herkie’’) founded the

National Cheerleader Association. The NCA is a for-profit enterprise

based in Dallas that runs hundreds of cheerleading camps nationwide,

teaching young aspiring cheerleaders jumping and cheering skills at a

reasonable rate. The cost of the camps is kept low, but the cheerleading

squads who attend the camps usually purchase their uniforms and

other accoutrements from the NCA-affiliated National Spirit group.

Since it costs about $200 to outfit the average cheerleader, 3 million

cheerleaders represent a sizable market, and by the 1990s, the NCA

was grossing over 60 million dollars a year.

The huge profits have attracted competition. In the 1970s, Jeff

Webb, a former protégé of James Herkimer, began his own company

in Memphis, the Universal Cheerleading Association, and its parent

company, the Varsity Spirit Corporation. While Herkimer has clung

to the classic cheerleading style, with athletic jumps and rhythmic

arm motions, Webb opted for a more modern approach; his camps

teach elaborate gymnastic stunts and dance routines, and his supply

company markets flashier uniforms and specialty items. Varsity

Spirit Corp. has even expanded abroad, signing a deal in Japan, where

cheerleading is very popular. Though NCA and UCA are the largest,

the expanding ‘‘school spirit industry’’ has prompted the creation of

many other cheerleading camp/supplier companies.

Because cheerleaders play such an important role in many

schools, cheerleading has become a battleground for social issues. In

1969 over half of the public school students in Crystal City, Texas,

staged a walkout for twenty-eight days in protest of their school’s

racist policies concerning cheerleader selection. In a district where 85

percent of the students were Chicano, it was not unusual for only one

Chicana cheerleader to be selected. The students’ action was success-

ful and it was the root of the Chicano movement organization, Raza

Unida. In 1993, four cheerleaders on a high school squad in Hempstead,

Texas, found they were pregnant. Only one was allowed to return to

cheering; she had an abortion, and she was white. The other students,

who were African American, fought the decision with the support of

the National Organization for Women and the American Civil Liber-

ties Union. They were finally reinstated. In 1991, another student

charged the University of Connecticut with discrimination when they

dropped her from the cheering squad for being, at 130 pounds, over

the weight limit. Her suit resulted not only in her reinstatement but in

the abolition of the weight requirement.

The fierce competition surrounding cheerleading has been docu-

mented in a cable-TV movie starring Holly Hunter in the title role of

The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-

Murdering Mom. The movie takes playful liberties with the true story

of Wanda Holloway, who plotted to have the mother of her daughter’s

CHEERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

488

cheerleading rival killed. Journalists in Texas, where cheerleading is

taken seriously, were surprised only by the fact that Holloway

presumed that the murder would prevent the rival from trying out for

the squad. The media is full of other such stories: the New Jersey

cheerleaders who in 1998 fed the opposing squad cupcakes filled with

laxatives, and the South Carolina cheerleaders who spiced up a

1995 Florida competition by holding their own private contest—

in shoplifting.

Cheerleaders are easy targets for satire, their raison d’être

construed as boosterism, and they are often stereotyped as being

stupid and superficial. In 1990, the University of Illinois was prompt-

ed to take the soft-core sexual image of cheerleaders seriously. Noting

the high rate of sexual assault on campus, a university task force

recommended banning the cheerleaders, the Illinettes, because the

all-female squad maintained a high-profile image as sexual objects. In

this light, it is easy to see that male cheerleading is a distinctly

different phenomenon; men in letter sweaters with megaphones

yelling and doing acrobatics clearly fill a different role than scantily-

clad women doing the same yells and acrobatics.

Debate continues over whether cheerleaders are athletes or

bimbos; whether cheerleading is, in itself, a sport, or an adjunct to the

real (mostly male) sports. Some women devote their lives to

cheerleading, for themselves or their daughters; some women con-

demn it because it turns women into boosters at best and sex objects at

worst. Some men delight in watching the dances of the flamboyant

squads at half-time; some men see them as a distraction to the game

and belive they should be abolished. And in junior high and high

schools across the country, girls, even many who profess not to care,

still train to perform difficult routines for tryouts and anxiously watch

bulletin boards to see if they made the squad.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American

Culture. Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling Green State University

Popular Press, 1995.

Ralston, Jeannie. ‘‘Rah! Power.’’ Texas Monthly. Vol. 22, No. 10,

October, 1994, 150.

Scholz, Suzette, Stephanie Scholz, and Sheri Scholz. Deep in the

Heart of Texas: Reflections of Former Dallas Cowboy Cheerlead-

ers. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Cheers

Cheers was the longest-running and most critically acclaimed

situation comedy on 1980s television. Combining physical and verbal

gags with equal dexterity, Cheers turned the denizens of a small

Boston bar into full-fledged American archetypes. By the end of the

show’s run, author Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., was moved to call Cheers the

‘‘one comic masterpiece’’ in TV history. The author of many comic

fiction classics added, ‘‘I wish I’d written [Cheers] instead of

everything I had written. Every time anybody opens his or her mouth

on that show, it’s significant. It’s funny.’’

Cheers was set at a Boston bar of the same name owned by Sam

Malone (Ted Danson), a good-looking former relief pitcher for the

woebegone Boston Red Sox whose career was cut short by a drinking

problem. His alcoholism under control, he reveled in his semi-

celebrity and status as a ladies’ man. Tending bar was Sam’s old Red

Sox coach, the befuddled Ernie Pantuso (Nicholas Colasanto), a

character obviously modeled on baseball great Yogi Berra. In early

1985, Colasanto suddenly died. He was replaced behind the bar by an

ignorant Indiana farm boy, Woody Boyd (Woody Harrelson). Carla

Tortelli (Rhea Perlman) was the foul-mouthed waitress; a single

mother, she bore several children out of wedlock during the show’s

eleven-year run. To one woman she threatened, ‘‘You sound like a

lady who’s getting tired of her teeth.’’ The bar’s regulars were the

pathetic Norm Peterson (George Wendt), a perpetually unemployed

accountant trapped in a loveless marriage to the unseen Vera; and

the equally pathetic Cliff Clavin (John Ratzenberger), the resident

trivia expert and career postal worker, who still lived with his

domineering mother.

In the series’ first episode Diane Chambers (Shelley Long), a

pretentious, well-to-do graduate student, was abandoned at the bar by

her fiancé en route to their wedding. Sam offered her a job waitressing,

thus beginning one of the most complex romances in prime time TV

history. Sam and Diane swapped insults for most of the first season,

and a volley of insults on the season’s last episode culminated in their

first kiss. They consummated their relationship in the first episode of

the second season:

SAM: You’ve made my life a living hell.

DIANE: I didn’t want you to think I was easy.

Yet Sam and Diane never tied the knot. Diane left Sam and

received psychiatric help from Dr. Frasier Crane (Kelsey Grammer),

with whom she promptly fell in love. Diane and Frasier planned a

European wedding, but she left him at the altar. By the 1986-87

season Sam and Diane were engaged when, on the eve of their

wedding, Diane won a sizable deal to write her first novel. Sam

allowed her to leave for six months to write, knowing it would

be forever.

Sam sold the bar to go on a round-the-world trip. He humbly

returned to become the bartender for the bar’s new manager, Rebecca

Howe (Kirstie Alley), a cold corporate type. The bar was now owned

by a slick British yuppie, Robin Colcord, who had designs on

Rebecca. When Robin was arrested for insider trading, Sam was able

to buy back the bar for a dollar.

Life went on for the Cheers regulars. Dumped by Diane, the

cerebral Frasier grew darker and more sarcastic, barely surviving a

marriage to an anal-retentive, humorless colleague, Lilith (Bebe

Neuwirth). Sam and Rebecca enjoyed a whirlwind romance and

contemplated having a baby together out of wedlock. Carla married a

professional hockey player, who was killed when a Zamboni ran over

him. Woody fell in love with a naive heiress, and by the final season

won a seat on the Boston City Council. Norm and Cliff remained

loyal customers, serving as Greek chorus to the increasingly

bizarre happenings.

Despite the wistful theme song (‘‘Sometimes you want to go /

Where everybody knows your name’’), the characters were frequent-

ly cruel to one another. Norm once stood up for the unpopular Cliff

this way: ‘‘In his defense, he’ll probably never reproduce.’’ During

one exchange Carla asked Diane, ‘‘Did your Living Bra die of

boredom?’’ They also engaged in elaborate practical jokes; Sam