Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Asher, George M., ed. Henry Hudson the Navigator. London: Hakluyt

Society

, 1860.

Johnson, Donald S., and Philip Turner, eds. Charting the Sea of Dark-

ness:

The F

our Voyages of Henry Hudson. New York: Kodansha

International, 1995.

P

owys, Llewelyn. Henry H

udson. N

ew York: Harper and Brothers,

1928.

Thomson, George Malcolm. The Search for the North-West Passage.

New Yor

k: Macmillan, 1975.

Hudson’s Bay Company

The Hudson’s Bay Company, founded in London in 1670

to develop the fur trade of British North America, estab-

lished British claims to northern and western Canada (see

C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

)

and opened western lands to settlement. The original char-

ter granted rights to “the Company of Adventurers from

England trading into the Hudson’s bay.”

The company was founded by English noblemen and

merchants with the help of two disgruntled French fur

traders, Médard Chouart, sieur des Groseilliers, and Pierre

Esprit Radisson, who agreed to work for Charles II (r.

1660–85). The original charter provided exclusive trading

rights for all lands drained by rivers flowing into Hudson

Bay, an area of almost 1.5 million square miles. Company

traders probed deep into the Canadian interior, trading guns,

knives, and other manufactured objects for furs, especially

beaver pelts. Although not organized for settlement, the

company required hundreds of employees, most of whom

were brought from Ireland and Scotland as indentured ser-

vants (see

INDENTURED SERVITUDE

). They frequently mar-

ried native women, and their families formed a distinct

ethnic group, the Métis, by 1800. Conflict with the French,

who claimed the same lands, was endemic. A series of colo-

nial wars, culminating in the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63),

led to complete British control of Canada and a free hand for

the Hudson’s Bay Company. With the demise of the French

threat, in 1779 the North West Company was formed in

Montreal to challenge the Hudson’s Bay Company’s domi-

nance of the fur trade. In order to compete, each company

extended its network of fortifications, trading posts, Indian

contacts, and transportation routes, thus opening isolated

western settlements to further European contact. After open

warfare between the two companies in the wake of the estab-

lishment of the R

ED

R

IVER COLONY

(1812), the rivals even-

tually merged and were reorganized (1821), retaining the

Hudson’s Bay Company name and extending the original

charter to include the Pacific Northwest and the Arctic.

As western Canada enticed larger numbers of settlers,

the fur trade declined as a major commercial enterprise, and

124124 HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY

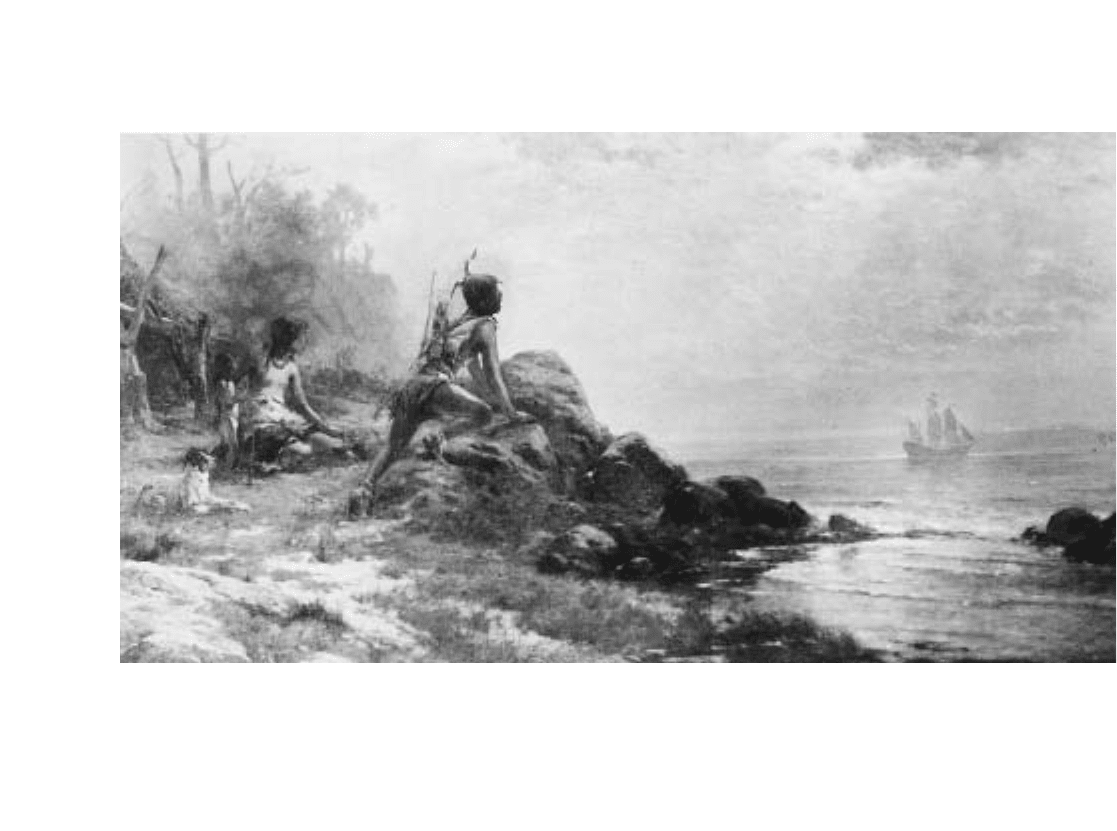

A romanticized view of American Indians first sighting Henry Hudson as he sails into NewYork Bay, September 11, 1609.After

many years of fruitlessly searching for the Northwest Passage, Hudson was in the pay of the Dutch East India Company in 1609

when he established Dutch claims to the region of modern NewYork.

(Painting by Edward Moran, ca. 1908/Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-107822])

the United States surfaced as a potential threat, company

administration of the huge area became untenable. In 1869,

the British government negotiated a settlement with the

Hudson’s Bay Company that transferred the company’s

lands to the newly formed Dominion of Canada (1867). In

return, the company received £300,000, a grant of some

45,000 acres around its 120 trading posts, and continued

trading privileges on the western plains. With the fur trade

almost dead by 1875, the company diversified its interests,

shifting greater resources into real estate and retail market-

ing operations and maintaining its position as one of the

largest private companies in Canada. In the wake of reces-

sion, in 1986 and 1987 the company sold its fur-auction

houses and petroleum interests in order to raise cash and

intensify the retailing and real estate sectors that have kept

the company solvent in the years since World War II.

Further Reading

Galbraith, John S. The Hudson’s Bay Company as an Imperial Factor,

1821–69. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

P

r

ess, 1957.

———. “Land Policies of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1870–1913.”

Canadian Historical Review 32 (March 1951): 1–21.

M

acKay, Douglas. The Honourable Company: A History of the Hud-

son’

s Bay Company. 2d rev. ed. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart,

1949.

N

e

wman, Peter C. Company of Adventurers. 2 vols. New York: Viking,

1985, 1987.

———. E

mpire of the Bay: The Company of Adventurers That Seized a

Continent. New York: Penguin, 2000.

Rich, E. E. Hudson’s Bay Company, 1670–1870. 3 v

ols. Toronto:

M

cClelland and Stewart, 1960.

Woodcock, George. The Hudson’

s Bay Company. Toronto: Collier-

Macmillan Canada, 1970.

Hughes, John Joseph (1797–1864) religious leader

As bishop (1838–50) and archbishop of New York

(1850–64), John Hughes was among the most influential

figures in what Roger Daniels calls the “Hibernization of the

American Roman Catholic Church.” As the first Catholic

archbishop of New York, he was an outspoken defender of

the Catholic Church, eloquently articulating its compati-

bility with traditional American political principles.

Hughes emigrated from northern Ireland to the

United States in 1817. After attending Mount Saint Mary’s

Seminary in Philadelphia, he was ordained in 1826. He

favored Irish nationalism generally but opposed violent

means of promoting it. During the 1830s, he waged a vig-

orous press debate with Protestant leaders over the ques-

tion of the validity of lay control of Catholic Church

property. After moving from Philadelphia to New York in

1838, Hughes campaigned vigorously against Protestant

influence in the nonsectarian public schools. Once he

became archbishop of New York in 1850, he was the pri-

mary spokesperson for the Catholic Church in defense of

nativist attacks from the Know-Nothing Party (see

NATIVISM

). Increasingly, he served the needs of the

Catholic hierarchy rather than the Irish themselves, though

he did continue to promote such organizations as the Irish

Emigrant Society, the Emigrant Savings Bank, and the

Ancient Order of Hibernians. Hughes’s influence grew

during the Civil War (1861–65), helping to shift the bal-

ance of ethnic influence within the church from French to

Irish clergy. Although Hughes was not an abolitionist, he

remained a firm unionist. He undertook a mission to

France on behalf of President Abraham Lincoln (1863)

and helped to quell the New York draft riots (1863).

125HUGHES, JOHN JOSEPH 125

An 1890s advertisement for the Hudson’s Bay Company

encourages Klondike prospectors to purchase the company’s

stores. After the decline of the fur trade in the 1870s, the

company diversified its economic interests and moved

extensively into commercial marketing.

(Library of Congress,

Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-104304])

Further Reading

Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860. 1938.

Reprint, Chicago: Q

uadrangle Books, 1964.

Braun, Henry A. Most Reverend John Hughes: First Archbishop of New

Yor

k. N

ew York: Dodd Mead, 1892.

D

olan, Jay. The Immigrant Church. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1975.

Lannie, Vincent P. Public M

oney and Parochial Education: Bishop

H

ughes, Governor Seward, and the New York School Controversy.

Cleveland, Ohio: Press of Case Western Reserve University,

1968.

S

haw

, Richard. Dagger John: The Unquiet Life and Times of Archbishop

John H

ughes of New York. New York: Paulist Press, 1977.

Huguenot immigration

French citizens who embraced the Protestant teachings of

the 16th-century reformation were known as Huguenots.

Because they were unwelcome in Catholic France, hun-

dreds of thousands left their native land, with several thou-

sand eventually making their way to the British colonies in

North America. Huguenots, generally prosperous and well

educated, were among the immigrant groups who were

rapidly assimilated into the dominant English culture of

America.

Huguenots attempted to settle in Florida (near present-

day St. Augustine), the Carolinas, and the Guanabara Bay

(in present-day Brazil) during the late 16th century, but

none of the settlements was successful. The first Huguenots

to settle successfully in the Americas sailed from the

Netherlands early in the 17th century, and a small number

followed throughout the century. Following Louis XIV’s

revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), which had guar-

anteed freedom of worship, several hundred thousand

Huguenots migrated to Holland, Prussia, and Britain, and

several thousand of these eventually made their way to the

Americas by the end of the 17th century. The exact number

is greatly disputed, in part because immigration records

were not routinely kept and because Huguenots often came

by way of a third country. Their favored destinations were

New York (New Rochelle and N

EW

Y

ORK

, N

EW

Y

ORK

),

Massachusetts (Oxford and Salem), Virginia, and the Car-

olinas (Charleston). Huguenots maintained their French

church traditions into the second generation but by the

1750s, began to rapidly integrate with English-language

Protestant churches. By the time of the American Revolu-

tion (1775–83), most Huguenots had lost their distinc-

tiveness, having married into English families, adopted the

English language, and adapted to the commercial and agri-

cultural developments of their regions. This process was

made easier by their relatively high social standing before

leaving France, many having been aristocrats and trained

artisans. Few Huguenots settled in Canada, as the French

government prohibited their permanent residence in N

EW

F

RANCE

.

Further Reading

Baird, Charles. History of the Huguenot Emigration to America. 2 vols.

1885. R

eprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1998.

Butler, Jon. The Huguenots in America: A Refugee People in New World

Society

. C

ambridge, Mass.: H

arvard University Press, 1983.

Golden, Richard M. The Huguenot Connection. Doordrecht, Nether-

lands: Mar

tinus Nijhoff, 1988.

Tobias, Leslie. “Manakin Town: The Development and Demise of a

French Protestant Refugee Community in Colonial Virginia,

1700–1750.” M.A. thesis, College of William and Mary, 1982.

Hull-House See A

DDAMS

,J

ANE

.

Hungarian immigration

One of the largest ethnic immigrant groups of the great

migration between 1880 and 1914, Hungarians built one of

the most cohesive ethnic identities in the New World. Accord-

ing to the 2000 U.S. census and the 2001 Canadian census,

1,398,724 Americans and 267,255 Canadians claimed Hun-

garian ancestry. The largest Hungarian concentrations in the

United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries were in

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Cleveland, and Youngstown, Ohio;

C

HICAGO

; P

HILADELPHIA

; and N

EW

Y

ORK

City. As later

generations aged, they frequently moved, most often to Cali-

fornia and Florida. Canadian cities with the largest Hungar-

ian population are T

ORONTO

and Vancouver.

Modern Hungary occupies 35,600 square miles in east

central Europe. It is bordered by Slovakia and Ukraine to the

north; Austria to the west; Slovenia, Yugoslavia, and Croa-

tia to the south; and Romania to the east. In 2002, the pop-

ulation was estimated at 10,106,017. The people are

ethnically divided, mainly between Hungarians (90 per-

cent), Gypsies (4 percent), and Germans (3 percent); 68 per-

cent are Roman Catholic; 20 percent, Calvinist; 5 percent,

Lutheran; and 5 percent, Jewish. The middle Danube River

basin was settled in the late ninth century by Asian warriors

known as Magyars, the name still used by Hungarians for

their group. The Magyars converted to Christianity around

1000. Although eventually abandoning seminomadic pas-

toralism and establishing a settled kingdom, their history in

the strategic Carpathian basin was full of conflict, princi-

pally with Slavs, whose lands they had invaded; Germans,

who were in the process of expanding eastward; and the

Ottoman Turks, who were pushing north from their home-

land in Anatolia. By the late 16th century, most of Hungary

was brought under the control of the Austrian Habsburgs.

After an abortive revolution in 1848–49 led by the dynamic

Lajos Kossuth, in 1867, Hungarians were finally granted

equal status with Austrians under the Austrian emperor. The

Dual Monarchy thereby created the Austro-Hungarian

Empire. The Hungarian portion of the empire was a micro-

cosm of the whole, made up of many ethnic groups, includ-

ing Germans, Slovaks, Gypsies, Serbs, Croats, and

126126 HUGUENOT IMMIGRATION

Romanians. After the Austro-Hungarian Empire was

defeated in World War I (1914–18), independent Hungary

was greatly reduced, stripped of most regions not predomi-

nantly inhabited by Magyars. The country joined forces

with Nazi Germany in an attempt to regain lost territories

during World War II (1939–45) and quickly fell under

Soviet control in the aftermath of the war. Although pro-

Soviet communists were temporarily driven from power in a

1956 revolt, the Soviet army invaded the country, savagely

suppressing the rebellion, leading to the exodus of some

200,000 Hungarians who became refugees, mostly in Aus-

tria. As the most liberal of all the Soviet satellites during the

COLD WAR

, Hungary moved relatively smoothly into inde-

pendence as the Soviet Union lessened its grip in 1989 and

quickly began to attract foreign investment.

There are accounts of notable Hungarians in North

America as early as the A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION

(1775–83).

At least one Hungarian was a part of Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s

expedition to North America in 1583. Between the 17th

and mid-19th centuries, a number of prominent Hungari-

ans came as individuals to America and generally left glow-

ing accounts of their experiences. Agoston Haraszthy not

only praised the new country in Journey to North America

(1844) but set an example that hundreds of thousands of

H

ungarians later follo

wed, bringing his family to settle per-

manently in California, where he established the new viti-

culture industry. The first significant occurrence of group

migration came in 1849–50, when several thousand Hun-

garian nationalists—the “forty-niners”—fled the country

following a failed revolution and settled in the United States.

Under Austrian domination, Hungary found itself in the

midst of a far-reaching social transformation as a result of

the abolition of serfdom. This freed the rural worker from

the land but also absolved welfare obligations of the land-

lord. The continued predominance of large estates through-

out most of the country made owning enough land to guard

against want virtually impossible for the rural proletariat.

U.S. railway and steamship agents took advantage of these

conditions, sending agents and propaganda into the

remotest regions of the country.

As impoverished Hungarians looked to emigration, they

relied on support from their extended family of aunts, uncles,

cousins, and in-laws. Despite the fact that Hungarian immi-

gration was driven by overpopulation and economic impov-

erishment—factors common to most European countries in

the 19th century—Hungary nevertheless sent a dispropor-

tionate number of migrants to the United States and Canada

prior to World War I. The first great wave came between

1880 and 1914, when more than 1.5 million Hungarians

immigrated to the United States, with more than 800,000

coming between 1900 and 1910. Most came from rural areas

but worked in American mines and factories, hoping one day

to return to their homeland. Maintaining such close ethnic

ties, they frequently were slow to assimilate.

As a result of the restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924), immigration between the world wars was greatly

reduced, to a total of about 40,000. As a result of World War

II, tens of thousands of Hungarians became displaced per-

sons, and about 25,000 entered the United States between

1945 and 1956, most under provisions of the D

ISPLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

(1948). A further phase of Hungarian immi-

gration was initiated with the abortive revolution against

Soviet control in 1956, leading to the admission of about

36,000 “fifty-sixers” who were admitted to the United States

as refugees. Between the revolt and independence in 1989,

about 18,000 Hungarians immigrated to the United States,

most because of dissatisfaction with communist politics and

economies. Following the demise of Soviet influence in

1989, Hungary went through a difficult economic transition

to market capitalism, leading to the exodus of many young

and well-educated professionals. Between 1989 and 2002,

the annual average immigration was about 1,000.

Large-scale Hungarian immigration to Canada began

somewhat later than to the United States, in conjunction

with the mass migration to Canada’s southern neighbor. The

first Hungarians arriving on the newly opened prairies of

present-day Manitoba in 1885 came by way of the Pennsyl-

vania coal mines, with the support of the Canadian Pacific

Railway. Although many eventually left the Assiniboia dis-

trict in what is now Alberta and Saskatchewan, by 1903,

the railway reached the settlement bringing more settlers

directly from Hungary. Canada was seen by Hungarian

church and social leaders as a potentially healthy alternative

to the harsh industrial landscape of the United States. By

World War I there were a half-dozen Hungarian settlements

in Canada, most in present-day Saskatchewan, but only

about 10,000 settlers. Facing the harsh realities of life under

the punitive Treaty of Trianon ending World War I, Hun-

garians found new reasons to immigrate. Most would have

preferred the United States, but restrictive immigration poli-

cies all but halted the flow there in the 1920s. Canada there-

fore became the foremost destination for Hungarians

coming to the New World. About 30,000 immigrated to

Canada between World War I and World War II, most

under a Railway Agreement by which Canadian railways

and the Canadian government sought agricultural settlers

for the western prairies. With few good farmsteads remain-

ing, most Hungarian immigrants gradually settled in central

Canada, specifically in Hamilton, Toronto, Welland, Wind-

sor, Montreal, and surrounding areas, where they became

active in ethnic, political, and mutual aid societies.

Canada admitted almost 12,000 Hungarian refugees

between 1946 and 1956, with most settling in Ontario and

other eastern cities. The revolt of 1956 led to the final mass

migration of Hungarians to Canada, more than 37,000 in

1956 and 1957. In both migrations, there were large per-

centages of well-educated professionals, which began to alter

the perception of Hungarians as poor agriculturalists and

127HUNGARIAN IMMIGRATION 127

128

ease the process of assimilation. Of 48,715 Hungarian

immigrants in Canada in 2001, fewer than 5,000 came

between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Dirk, Gerald. Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunity.

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977.

D

r

eisziger, N. F., ed., with M. L. Kovács, Paul Bôdy, and Bennet

Kovrig. Struggle and Hope: The Hungarian-Canadian Experience.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

G

latz, Ferenc, ed. Hungarians and Their Neighbors in Modern Times,

1867–1950. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

G

rácza, R

ezsoe, and Margaret Grácza. The Hungarians in America.

Minneapolis, Minn.: Lerner, 1969.

K

eyserlingk, R

obet H., ed. Breaking Ground: The 1956 Hungarian

Refugee M

ovement to Canada. Toronto: York Lanes, 1993.

Kósa, John. Land of Choice:

The Hungarians in Canada. Toronto: Uni-

versity of

Toronto Press, 1957.

Kovács, Martin. Esterházy and Early Hungarian Immigration to

Canada. Regina: Canadian Plains S

tudies, 1974.

Lengyel, Emil. Americans from Hungary. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott,

1948.

Miska, J

ohn. Canadian Studies on Hungarians, 1886–1986. Regina:

Canadian Plains Research Center, 1987.

Patrias, Carmela. The Hungarians in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian His-

torical Association, 1999.

———. Patriots and Proletarians: Politicizing Hungarian Immigrants

in I

nter

war Canada. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press,

1994.

P

uskás, J

ulianna. From Hungary to the United States (1880–1914).

Budapest, Hungary: Akademiai Kiado, 1982.

Romanucci-Ross, L., and G. DeVos., eds. Ethnic Identity: Creation,

Conflict, and Accommodation. 3d ed.

Walnut Creek, Calif:

AltaMira Press, 1995.

Széplaki, Joseph, ed. The Hungarians in A

merica, 1583–1974: A

Chronology and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publica-

tions,1975.

T

ezla, Albert. The Hazardous Quest: Hungarian Immigrants in the

U

nited S

tates, 1895–1920. Budapest, Hungary: Corvina, 1993.

Várdy

, Steven B. The Hungarian Americans. Boston: Twayne, 1985.

———. The Hungarian Experience in North America. New York and

P

hiladelphia: Chelsea H

ouse, 1990.

Weinstock, S. A. Acculturation and Occupation: A Study of the 1956

H

ungarian R

efugees in the United States. The Hague, Nether-

land: Nijhoff

, 1969.

Hutterite immigration (Hutterian Brethren

immigration)

The Hutterian Brethren (Hutterites) are a communal

Anabaptist P

r

otestant sect that emigrated en masse from

Russia to the United States in the 1870s. Large numbers of

them then moved to the southern Canadian prairies begin-

ning in 1919. They were one of the few ethnic communi-

ties to retain most of the distinctive features of their religious

and ethnic roots throughout the 20th century. In 2003,

there were approximately 36,000 Hutterites living in 434

“colonies” in North America. In Canada, they were concen-

trated in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba; in the

United States, most of the colonies were in South Dakota

and Montana.

Emerging from the Anabaptist movement of the Protes-

tant Reformation in 1528, the Hutterite Brethren, like the

Amish (see A

MISH IMMIGRATION

) and Mennonites (see

M

ENNONITE IMMIGRATION

), believed in adult baptism and

in pacifism. They also lived communally, holding all goods

in common, a practice that often put them at odds with

their neighbors. Originally German-speaking Swiss, they

migrated to Moravia, in the present-day Czech Republic. In

1536, their leader, Jacob Hutter, was burned at the stake,

leading to an ongoing migration in search of refuge. Hut-

terites were hardworking and well organized and thus fre-

quently welcomed in other lands. They were nevertheless

viewed with suspicion and envy, especially during hard eco-

nomic times. Their communal lifestyle and use of Tyrolean

German continued to set them apart from the native inhab-

itants around them. As a result, they were persecuted and

driven successively from Austria, Moravia, Slovakia, Tran-

sylvania (Romania), and Wallachia (Romania). During the

18th century, most Hutterites migrated to the Ukraine,

where the Russian czar promised freedom of worship and

freedom from military service.

When Russian guarantees were rescinded in the

1870s, the Hutterites began a mass migration to the

United States and Canada. Between 1874 and 1877, vir-

tually all Hutterites—approximately 1,300—immigrated

to the Dakota Territory. Several hundred left the commu-

nal church, eventually merging with more liberal Men-

nonites, though most retained their traditional social

organization. Persecuted and fearing conscription during

World War I (1914–18), a large group of Hutterites deter-

mined to move to Canada in 1918, founding six colonies

in southern Manitoba and nine in southern Alberta.

Although restrictions were placed on Hutterite immigra-

tion (1919–22) and on land purchases in Alberta

(1942–72), their rural, isolated colonies prospered.

Further Reading

Gross, Leonard. The Golden Years of the Hutterites. Scottdale, Pa.:

Herald Press, 1980.

H

ostetler, John A. Hutterite Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Uni-

v

ersity P

ress, 1974.

Janzen, William. Limits on L

iberty: The Experience of Mennonite, Hut-

terite, and D

oukhobor Communities in Canada. Toronto: Univer-

sity of T

oronto Press, 1990.

Ryan, John. The Agricultur

al E

conomy of Manitoba Hutterite Colonies.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1977.

128 HUTTERITE IMMIGRATION

Icelandic immigration

Sharing a common North Atlantic heritage with Canada,

Iceland became one of the few source countries to send more

immigrants to Canada than to the United States. It was also

one of the few countries whose emigration virtually ceased

by 1910. According to the U.S. census in 2000 and the

Canadian census in 2001, 42,716 Americans and 75,090

Canadians claimed Icelandic origins. California and Wash-

ington State had the largest number of Icelandic settlers in

the United States, while Ontario, Manitoba, and British

Columbia had the largest populations in Canada.

Iceland is an island country in the North Atlantic

Ocean, occupying 38,700 square miles. Its nearest neighbors

are Greenland, about 200 miles to the west, and the Faeroe

Islands of Denmark, about 250 miles to the east. In 2002,

the population was estimated at 277,906. About 95 percent

are Icelandic, mainly descended from Norwegians and Celts,

and some 95 percent are Protestant, mostly Evangelical

Lutheran. Iceland was an independent republic from 930

to 1262, when it joined with Norway. Denmark incorpo-

rated Norway in 1380, and with it Iceland. Direct Danish

rule lasted until 1918, when Iceland was granted autonomy

under the Danish king. The last ties with the Danish Crown

were finally severed in 1944, when Iceland became an inde-

pendent republic. The Althing (assembly), is the world’s old-

est surviving parliament.

A few dozen Mormon converts from Iceland immi-

grated to Utah after 1854, but no large-scale migration fol-

lowed. The greatest period of migration for Icelanders was

the 1870s. Spurred by harsh conditions, unproductive soil,

and a number of volcanic eruptions, several thousand Ice-

landers settled in Canada, most along the western shore of

Lake Winnipeg in what was then the Northwest Territories.

With a delay in establishment of territorial government, the

Icelanders were given permission to form their own admin-

istrative unit known as New Iceland in 1878. Self-govern-

ment lasted until 1887, when the new Manitoba

government took over. In 1878, about 30 families moved

from New Iceland to North Dakota, joining fewer than 200

Icelandic immigrants who had settled in Wisconsin and

Minnesota earlier in the decade. From their base in Win-

nipeg, which boasted an Icelandic population of 7,000 dur-

ing the late 19th century, Icelanders began to spread

throughout the wheat lands of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

It is impossible to say exactly how many Icelanders came to

North America during the 19th century, as they were usually

counted as Danes. It is estimated conservatively that about

10,000 immigrated to Canada and about half that number

to the United States. As conditions improved in Iceland after

1900, immigration declined dramatically. In 2001, only 415

Icelander immigrants resided in Canada, and more than half

of these arrived before 1970. Immigration to the United

States averaged about 130 per year between 1992 and 2002.

Further Reading

Arnason, David, and Vincent Arnason, ed. The New Icelanders: A

North American Community

. Winnipeg, Canada: Turnstone

P

ress, 1994.

129

4

I

Arngrímsson, Gudjón. N´yja Ísland: Saga of the Journey to New Ice-

land. Winnipeg, Canada: Turnstone Press, 1997.

Bjornson, V

al. “Icelanders in the United States.” In Scandinavian

Review 64, no

. 3 (September 1976): 39–41.

Kristjanson, W

ilhelm. The Icelandic People in Manitoba: A Manitoba

Saga. W

innipeg, Canada: Wallingford Press, 1965.

Palmer, H. “Escape fr

om the Great Plains: The Icelanders in North

Dakota and Alberta.” Great Plains Quarterly 3, no. 4 (Fall 1983):

219ff

.

Pennings, M

argaret. “The Big Store: The Story of Icelandic Immigra-

tion in America,” B.A. thesis, University of Minnesota.

Regan, A. “Icelanders.” In They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s

E

thnic G

roups. Ed. S. Thernstrom. St. Paul: Minnesota Histori-

cal Society P

ress, 1981.

Rosenblad, Esbjörn, and Rakel Sigurdardó Hir-Rosenblad. Iceland

fr

om P

ast to Present. Trans. Alan Crozier. Reykjavík: 1993.

The Settlement of New Iceland. Rev. ed. Winnipeg, Canada: Manitoba

C

ultur

e, History, and Citizenship, Historic Resources Branch,

1997.

Thorson, P. V. “Icelanders.” In Plains F

olk: North Dakota’s Ethnic His-

tor

y. Eds. W. C. Sherman and P. V. Thorson. Fargo: North

Dakota I

nstitute for Regional Studies, 1986.

Walters, Thorstina Jackson. Moder

n Sagas: The Story of the Icelanders in

A

merica. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies,

1953.

illegal immigration

Until the 1990s, the term most commonly used for those

who entered the United States illegally was illegal alien. An

alien was defined by the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZA

-

TION

S

ERVICE

(INS) as “any person not a citizen of the

United States.” Any alien who enters and resides in the

country in violation of immigration law is an illegal alien.

During the 1990s, the government and governmental

authorities increasingly used the term unauthorized resident

as a synonym. The term most commonly used in Canada is

undocumented migrant. Aliens, whether legal or illegal, still

enjo

y most of the rights and pr

otections afforded by both

governments. Unlike citizens, however, they are subject to

deportation for breaches of the law. As potential immigrants

around the world began to perceive the potential for secur-

ing better jobs, education, and health care in the 1970s in

the United States and Canada and increasingly found means

for getting there, illegal immigration became a major policy

concern. It also led to a new wave of anti-immigration

activism, particularly in the American Southwest, and a

public debate that had still not been resolved in the first

decade of the 21st century.

Until 1917, the United States had a largely open immi-

gration policy; the biggest immigration questions revolved

around legal, rather than illegal, immigration. Between

1875 and 1917, a number of restrictive measures were

passed to exclude prostitutes, convicts, “lunatics,” “idiots,”

and the indigent (see I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(1906); P

AGE

A

CT

), but these affected few people. More significant were

the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882) and the G

ENTLE

-

MEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

(1907), which led to the exclusion of

most Chinese and Japanese laborers. Although some labor-

ers found their way into the country, mainly through colo-

nial Hawaii, where they were still allowed as laborers, illegal

immigration did not affect the country generally. The tight

restrictions of the E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

of 1921 and

the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924, however, led to a flood of

illegal immigration in the 1920s. Canada offered some

cooperation, but Mexico was unresponsive, and Chinese

immigrants especially continued to pour across both bor-

ders. As early as 1904, Bureau of Immigration inspectors

routinely patrolled almost 2,000 miles of Mexican border,

but the 75 agents assigned to the task were scarcely able to

prevent illegal entry. With drastically reduced quotas fol-

lowing the immigration reform of 1924 came establishment

of the U.S. B

ORDER

P

ATROL

, an enforcement agency of the

Department of Labor.

The dramatic increase in immigration after 1965 was in

large measure a function of the provisions of the I

MMIGRA

-

TION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965 and government

perception of

COLD WAR

needs to exclude especially Cubans

and Vietnamese from the ordinary provisions of immigra-

tion policy. At the same time, however, illegal immigration

exploded, as legal migrant laborers under the Bracero Pro-

gram became illegal immigrants once the program was

ended (1965). With the INS understaffed and U.S. employ-

ers exempt from criminal prosecution for hiring illegal

immigrants, cheap foreign labor continued to pour into the

country. Between 1970 and 1997, more than 30 million ille-

gal immigrants were apprehended, though deportations

were often difficult, and millions more eluded interception

and entered the labor force.

The number of unauthorized immigrants in the United

States rose dramatically in the 1990s. An INS report of

February 1997 showed that there were an estimated 5 mil-

lion illegal immigrants in the United States as of October

1996; four years later, the number had risen to 7 million

(8.7 million according to the U.S. Census Bureau), further

heightening the public debate over American responsibility

toward poor, illegal immigrants. Almost 70 percent of unau-

thorized residents in 2000 were from Mexico, and another

14 percent from El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Hon-

duras, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic. About 40

percent entered with tourist or worker visas but failed to

return to their home countries when the visas expired. After

years of debate, the U.S. Congress passed the I

LLEGAL

I

MMI

-

GRATION

R

EFORM AND

I

MMIGRANT

R

ESPONSIBILITY

A

CT

in 1996, which increased the Border Patrol, provided for

stiffer penalties in trafficking undocumented aliens, and

made deportation easier. In March 2000, Vice President Al

Gore proposed to expand the 1986 Immigration Act, which

granted residency to immigrants who had lived continu-

130130 ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION

ously in the United States since 1972, to include those who

had lived in the United States since 1986. As a result, some

500,000 undocumented immigrants were granted residency.

Canadian economic opportunities were fewer than in

the United States, the attitude toward non-British immi-

grants more hostile, and the distances greater, so the inci-

dence of illegal immigration was less and had less national

impact. With the rapid progress of decolonization around the

world, however, and passage of the

IMMIGRATION REGULA

-

TIONS

of 1967, two significant waves of undocumented

immigration occurred. Between 1970 and 1973, more than

200,000 people applied for landed immigrant status. Under

Section 34 of the regulations, it became permissible to apply

within Canada and be guaranteed the right of appeal if

denied. Thousands of potential immigrants from around the

world took advantage of this administrative loophole, realiz-

ing that there would be a huge backlog of cases that would

permit settlement. With up to 8,700 applications a month by

October 1972, the Canadian government revoked Section 34

while offering the Adjustment of Status Program, essentially

an amnesty. By the end of 1973, about 52,000 previously

undocumented immigrants had been granted landed immi-

grant status. With economic depression looming in 1980,

public opposition to immigration began to increase, along

with the number of undocumented immigrants. Most of the

increase involved claims for refugee status, many of which

were bogus and clearly designed to give undocumented

immigrants an opportunity to gain a foothold in Canada (see

H

ONDURAN IMMIGRATION

). Provisions of B

ILL

C-55 and

B

ILL

C-84, which went into effect in 1989, streamlined the

refugee determination process, increased penalties for those

transporting undocumented migrants, and enhanced the

government’s powers of deportation. By the late 1990s, some

were estimating that as many as 16,000 illegal immigrants

were entering Canada annually, at a cost of up to $50,000 in

social benefits for each immigrant.

With many of the 19 hijackers involved in the terrorist

bombings of S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001, being illegal aliens, the

debate over illegal immigration was renewed in both the

United States and Canada, and more stringent measures

were introduced for screening and tracking immigrants and

for deporting illegal aliens. In the first decade of the 21st

century, illegal immigration from Mexico was the top U.S.

concern and led to high-level discussions between the two

governments. Canada’s biggest concern was human traffick-

ing from China and the high number of refugee claims by

Chinese immigrants.

See also

NATIVISM

.

Further Reading

Campbell, Charles M. Betrayal and Deceit: The Politics of Canadian

Immigr

ation. West Vancouver, Canada: Jasmine Books, 2000.

Corcoran, M

ary. Irish Illegals: Transients between Two Societies. West-

port, Conn.: G

reenwood Press, 1993.

Corona, Bert. Bert Corona Speaks on La Raza Unida Party and the “Ille-

gal A

lien” Scare. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972.

Espenshade, T

. J. “A Short History of U.S. Policy toward Illegal Immi-

gration.” Population T

oday 1

8, no. 2 (February 1990): 6–9.

Haines, David W., and Karen E. Rosenblum. Illegal Immigration in

America: A R

eference Handbook. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood

Press, 1999.

K

yle, David, and Rey Koslowski, ed. Global Human Smuggling: Com-

par

ativ

e Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

2001.

K

wong, P

eter. Forbidden Workers: Illegal Chinese Immigrants and Amer-

ican Labor. N

ew York: New Press, 1998.

Malkin, M

ichelle. Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists,

Criminals and O

ther Foreign Menaces to Our Shores. New York:

Regner

y, 2002.

Smith, Paul J., ed. Human Smuggling: Chinese Migrant Trafficking

and the Challenge to A

merica

’s Immigration Tradition. Washing-

ton, D.C.: Center for Strategic and I

nternational Studies, 1997.

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant

Responsibility Act

(IIRIRA) (United States)

(1996)

As part of a 1996 initiative to curb illegal immigration, the

U.S. Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and

I

mmigrant R

esponsibility Act (IIRIRA). The measure

authorized a doubling of the number of U.S. B

ORDER

P

ATROL

agents between 1996 and 2001 (5,000 to 10,000)

and the building of additional fences along the U.S.-Mexi-

can border south of San Diego, in California. It also pro-

vided tougher penalties for those engaged in document

fraud and alien smuggling and greater controls on public

welfare provided to illegal aliens. The most controversial

aspects of the measure involved the streamlining of deten-

tion and deportation hearings. This enabled illegal aliens

to be deported without appeal to the courts, unless they

could demonstrate a realistic fear of persecution in their

home country. A review of decisions was required within

seven days but could be conducted by telephone or tele-

conference.

President Bill Clinton did not favor many of the harsh-

est elements of the measure and sought to reverse them

through vigorous promotion of the U.S.-Mexican Bina-

tional Commission and its Working Group on Immigra-

tion and Consular Affairs. Clinton also strongly supported

passage of the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central Ameri-

can Relief Act (NACARA), which effectively granted

amnesty to many Central American refugees whose status

had remained ambiguous since the 1980s civil war in

Nicaragua. In 1999, the Supreme Court let stand lower

court rulings allowing appeal to the courts. The harsher pro-

visions of the IIRIRA led to introduction in Congress of a

bill called the Restoration of Fairness in the Immigration Act

of 2000, which sought to eliminate retroactive consideration

of minor crimes and to provide for adequate judicial review

131ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION REFORM AND IMMIGRANT RESPONSIBILITY ACT 131

of judgments. As of mid-2004, the proposed act remained in

committee.

Further Reading

Espenshade, T. J., J. L. Baraka, and G. A. Huber. “Implications of the

1996 W

elfare and Immigration Reform Acts for U.S. Immigra-

tion.” Population and D

e

velopment Review 23, no. 4 (December

1997): 769–801.

Reimers, David. Unwelcome Strangers: American Identity and the Turn

Against I

mmigr

ation. New York: Columbia University Press,

1998.

Immigration Act (Canada) (1869)

Seeking to encourage economic development in the new

dominion, Canada’s first piece of immigration legislation

was designed to attract productive immigrants. With immi-

grant entry now under the auspices of the Ministry of Agri-

culture, the act was intended to ensure safe passage for

immigrants, to regulate abuses commonly perpetrated

against the new arrivals by unscrupulous businessmen, and

to encourage settlement. The measure was nevertheless a

failure, as most immigrants continued on to the United

States.

The Immigration Act contained few restrictions. It pro-

hibited entry of paupers unless the shipmaster provided

temporary support. In 1872, the measure was amended to

prohibit criminals. The act required those soliciting business

from immigrants to obtain a license. Boardinghouses were

required to clearly post their rates. The measure also pro-

vided for government agents to assist immigrants in arrang-

ing lodging and making connections to their chosen

destinations. This service eventually led to the establishment

of reception centers in Halifax, Nova Scotia; Montreal and

Quebec, Quebec; Kingston and Toronto, Ontario; and

Winnipeg, Manitoba, where temporary lodging and meals

could be found, along with advice regarding local labor

opportunities and transportation. The government provided

discount passage rates for domestic workers, who were in

high demand. Benevolent societies such as the Women’s

National Immigration Society ensured that the protection of

women was a priority, leading to 1892 amendments pro-

hibiting seduction by ships’ crew members. Special agents

also were provided to assist women in port, and special rail-

cars were designated for transportation to other parts of

Canada.

Further Reading

Johnson, Stanley C. A History of Emigr

ation from the United Kingdom

to North America, 1763–1912. London: G. Routledge, 1913.

Kealey

, Linda, ed. A Not Unreasonable Claim: Women and Reform in

Canada, 1880s–1920s. T

oronto: Women’s Press, 1979.

K

elley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

Histor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Toronto P

ress, 1998.

Parr, Joy. Labouring Childr

en: B

ritish Immigrant Apprentices to

Canada, 1869–1924. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University

Pr

ess, 1980.

Prentice, Alison, and Susan Trofimenkoff, eds. The N

eglected Majority:

E

ssays in Canadian Women’s History. 2 vols. Toronto: McClelland

and S

tewart, 1985.

Immigration Act (Canada) (1906)

The capstone of Minister of the Interior Frank Oliver’s

immigration policy, the Immigration Act of 1906 consoli-

dated all Canadian immigrant legislation, thus making it

easier for “the Department of Immigration to deal with

undesirable immigrants.” The measure greatly expanded

the number of exclusion categories, gave legislative weight

to the process of deportation, and set the tone for the gen-

erally arbitrary expulsion of undesirable immigrants that

characterized Canadian policy throughout much of the

20th century.

Among the excluded categories of immigrants were

prostitutes and others convicted of crimes of “moral turpi-

tude”; epileptics, the mentally challenged, and the insane;

the hearing, sight, and speech impaired; and those with

contagious diseases. The act also made the transportation

companies responsible for the costs of deportation of both

illegal immigrants and those who became public burdens

within two years of arrival. The minister of the interior was

given the authority to deny entry to anyone not arriving

directly from the land of his or her birth or citizenship, a

measure implemented by P.C. 27 in 1908 and used to

effectively deny entry to Japanese and Chinese citizens

who had first traveled to Hawaii. Most important, the

1906 Immigration Act established an arbitrary system in

which a board of inquiry named by the minister of the

interior passed judgment on admissibility, while all appeals

were heard by the minister. The powers of the immigration

service were also greatly enhanced by enabling it to pass

any regulation “necessary or expedient” for attaining the

measure’s “true intent.” Although Liberals and industrial-

ists generally preferred a more open policy, the prevailing

mood in the country was one of caution, seeking to avoid

many of the urban problems associated with the relatively

open immigration policies of the United States.

Further Reading

Johnson, Stanley C. A History of Emigr

ation from the United Kingdom

to North America, 1763–1912. London: G. Routledge, 1913.

Kealey

, Linda, ed. A Not Unreasonable Claim: Women and Reform in

Canada, 1880s–1920s. T

oronto: Women’s Press, 1979.

K

elley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

Histor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Toronto P

ress, 1998.

Parr, Joy. Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to

C

anada, 1869–1924. M

ontreal: McGill–Queen’s University

Press, 1980.

132132 IMMIGRATION ACT (CANADA) (1869)

Immigration Act (Canada) (1910)

A number of orders-in-council and regulations pursuant to

the 1906 I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

were further codified in the

Immigration Act of 1910, which granted the cabinet wide

discretionary power to regulate all areas of immigration. The

measure expanded the prohibited immigrant categories of

1906 to include those who would advocate the use of “force

or violence” to create public disorder, the “immoral,” and

charity cases who had not received clearance from either the

superintendent of immigration in Ottawa or the assistant

superintendent of emigration in London. This act also intro-

duced the three-year residency requirement for establishing

“domicile.” Until domicile was established, an immigrant

was subject to deportation if judged “undesirable.” The

duties of the boards of inquiry were expanded, and medical

examinations were conducted on those coming by land, as

well as sea. While the act did not single out particular racial

or ethnic groups, Section 38 did allow the cabinet to restrict

“immigrants belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the

climate or requirements of Canada.” This remained the eth-

nic basis for Canadian immigration policy until 1967.

Orders-in-council later in the year demonstrated the wide

power of the cabinet, establishing a $200 head tax on Asian

immigrants (P.C. 926) and a $25 monetary requirement for

entry (P.C. 924).

Further Reading

Johnson, Stanley C. A History of Emigration from the United Kingdom

to N

orth America, 1763–1912. London: G. Routledge, 1913.

Kealey

, Linda, ed. A Not Unreasonable Claim: Women and Reform in

C

anada, 1880s–1920s. Toronto: Women’s Press, 1979.

Kelley

, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

Histor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Tor

onto Press, 1998.

Parr, Joy. Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to Canada,

1869–1924. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1980.

Immigration Act (Canada) (1919)

In the wake of World War I (1914–18; see W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

) and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in

Russia, and in the midst of an economic depression, the

Canadian government amended its I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of

1910 to protect against subversive activities and to limit the

entry of those who might become involved in them. The

revisions were supported by the business community, which

had previously supported a more liberal policy. According to

the president of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association,

while Canada had millions of “vacant acres” that needed

population, “it is wiser to go slowly and secure the right

sort of citizens.”

Under Section 3 of the new Immigration Act, an order-

in-council excluded entry of emigrants from countries that

had fought against Canada during the war. The list of inad-

missible immigrants was also expanded to include alco-

holics, those of “psychopathic inferiority,” mental “defec-

tives,” illiterates, those guilty of espionage, and those who

believed in the forcible overthrow of the government or who

“disbelieved” in government at all. At the same time, revi-

sions made it easier to deport immigrants. If it could be

shown that an immigrant fell into an inadmissible class

upon arrival in Canada, he or she was no longer safe from

deportation after five years. Furthermore, the cabinet was

authorized to prohibit entry to members of any race, class,

or nationality because of contemporary economic condi-

tions or because they were not likely to be assimilable

because of “peculiar habits, modes of life and methods of

holding property,” a provision invoked against the entry of

Hutterites (see H

UTTERITE IMMIGRATION

), Mennonites

(see M

ENNONITE IMMIGRATION

), and Doukhobors. Addi-

tionally, in 1921, adult immigrants were required to have

$250 upon landing, and children, $125. Farm laborers and

domestic workers with previous job arrangements were

exempted from the landing fees. In 1923, immigration was

restricted to agriculturalists, farm laborers, and domestic ser-

vants only.

Further Reading

Avery, Donald. “Dangerous Foreigners”: European Immigrant Workers

and Labour Radicalism in C

anada, 1896–1932. Toronto:

McClelland and S

tewart, 1979.

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1998.

Parr

, Joy. Labouring Children: British I

mmigrant Apprentices to Canada,

1869–1924. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University P

ress, 1980.

Immigration Act (Canada) (1952)

The Immigration Act of 1952 was the first new immigration

legislation since 1910. It was officially described as an act

that “clarified and simplified” immigration procedures that

had evolved across four decades, but it further established

the cabinet’s ample discretionary powers over immigration.

It defined wide-ranging powers of the minister of citizenship

and immigration and clearly established the principle that

the governor-in-council could prohibit or limit immigration

on the basis of a wide range of suitability issues, including

race, ethnicity, citizenship, customs, health, and probable

success of assimilation. The doctrine of “suitability,” estab-

lished in 1906 and 1910, remained the foundation of Cana-

dian immigration policy throughout the 20th century. The

Immigration Act went into effect on June 1, 1953, along

with Order-in-Council P.C. 1953–859 (“Immigration Reg-

ulations”).

The measure defined the rights of admission for Cana-

dian citizens and those with Canadian “domicile.” At the

same time, it exhaustively listed prohibited classes, including

133IMMIGRATION ACT (CANADA) (1952) 133