Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

criminals, subversives, “idiots,” epileptics, beggars, the

insane, the “ill,” the physically “defective,” and prostitutes.

In addition to these categories, which had been part of the

1910 measure, homosexuals, drug addicts, and drug traf-

fickers were added. There were no specific limits. British

subjects from the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand,

and South Africa and Irish, French, and U.S. citizens were

allowed to immigrate under the measure so long as they

could support themselves until finding employment. Asian

immigration was limited to spouses or unmarried children

under the age of 21 of Canadian citizens. The measure also

provided a series of administrative prerogatives for ensuring

control, including right of examination and conditions for

arrest and deportation of those failing to meet standards. For

immigrants who did qualify for admission, the Immigra-

tion Act offered some support. It made exploitation of

immigrants a criminal offense and provided interest-free

travel loans to immigrants deemed necessary for Canadian

economic development.

The major weaknesses of the measure revolved around

the almost unlimited discretionary power granted to the

minister of citizenship and immigration. According to Sec-

tion 39, no court or judge was allowed to “review, quash,

reverse, restrain or otherwise interfere with any proceeding,

decision or order of the Minister, Deputy Minister, Director,

Immigration Appeal Board, Special Inquiry Officer or

immigration officer” in reference to detentions or deporta-

tions unless the person enjoyed Canadian citizenship or

domicile. With every case potentially under review by the

minister, the bureaucracy was overworked. And as the lan-

guage of the measure was essentially negative and favored

exclusion, there was a presumption that immigration officers

would not offer fair hearings. The measure was especially

hard on immigrants from newly independent India, Ceylon,

and Pakistan. As disappointed applicants applied to mem-

bers of Parliament and lawyers for assistance, the legal weak-

nesses in the measure became apparent.

Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Attorney

G

ener

al of Canada v. Brent (1956), the government was

required to pass new regulations r

educing discretionary

powers of admission and establishing categories of preferred

status. Privy Council order 1956–785 (1956) divided

admissible immigrants into four categories:

1. British subjects born or naturalized in the United

Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa;

citizens of Ireland, the United States, or those born

or naturalized in France or the islands of Saint-Pierre

and Miquelon, providing they could support them-

selves while finding employment

2. citizens of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, West Ger-

many, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg,

the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden,

or Switzerland, who found employment under the

direction of the Department of Citizenship and

Immigration, or who could establish themselves in

business

3. citizens of any country of Europe or the Western

Hemisphere, or of Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, or Turkey,

whose relatives were both legal residents and willing

to sponsor the proposed immigrant

4. citizens of any other country who were spouses of

Canadian citizens or unmarried children under the

age of 21

By 1962, most elements of racial and ethnic discrimination

had been eliminated, replaced with standards emphasizing

skills, education, and training. Rather than produce a com-

pletely new measure, however, political complications led the

Canadian government to amend the regulations. The amend-

ments of 1967, creating a new Immigration Appeal Board,

addressed the most glaring weakness of the measure but were

considered inadequate by most critics. In 1973, the Depart-

ment of Manpower and Immigration, formed in 1966, began

a review of Canadian immigration policy, but an inadequate

green paper led to nationwide public hearings on the matter

under a special joint committee of the Senate and the House

of Commons during 1975. The findings of the committee led

directly to the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1976.

Further Reading

Corbett, David C. Canada’s Immigration Policy: A Critique. Toronto:

Univ

ersity of Toronto Press, 1957.

Hawkins, Freda. Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public

Concer

n

. 2d ed. Kingston and Montreal: McGill–Queen’s Uni-

versity P

ress, 1988.

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

H

istor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Tor

onto Press, 1998.

Immigration Act (Canada) (1976)

The Immigration Act of 1976 marked a significant shift in

Canadian immigration policy in limiting the wide discre-

tionary powers of the minister of manpower and immigra-

tion. One of its major provision, in Section 7, required the

minister to consult with the provinces regarding demo-

graphic factors and levels of immigration. Although the act

coordinated the policies established in the 1952 Immigra-

tion Act and the various regulations subsequently passed, for

the first time it expressly stated the goals of Canadian immi-

gration policy, including family reunion, humanitarian con-

cern for refugees, and targeted economic development. The

measure, along with its attending regulations, nevertheless

continued to promote a “Canadians first” policy and was

designed to “support the attainment of such demographic

goals as may be established by the government of Canada

from time to time in respect of the size, rate of growth,

134134 IMMIGRATION ACT (CANADA) (1976)

structure and geographic distribution of the Canadian pop-

ulation.” The act took effect on April 10, 1978. It was

amended more than 30 times, including major revisions in

1985 and 1992, before being replaced in 2002 with the

I

MMIGRATION AND

R

EFUGEE

P

ROTECTION

A

CT

.

In 1973, the Department of Manpower and Immigra-

tion began a review of Canadian immigration policy, but an

inadequate green paper led to nationwide public hearings on

the matter under a special joint committee of the Senate and

the House of Commons during 1975. The findings of the

committee led directly to the Immigration Act of 1976. The

new measure established three categories of immigrant: fam-

ily class, independent class, and humanitarian class. Priority

was given to family class immigrants. Independent immi-

grants, usually the most prosperous, applied on their own

initiative and competed in a points system that suggested

their ability to fill an economic need in Canada and to be

successful. Within the independent class, skilled workers

qualified under a nine-factor points system that assigned

numerical values to education (16 points), vocational prepa-

ration (18 points), occupation demand (10 points), experi-

ence (8 points), arranged employment (10 points),

demography (10 points), age (10 points), language (15

points), and personal suitability (10 points). A minimum of

70 points were required to qualify. Entrepreneurs were

required to demonstrate that their ownership of a business

would provide support for a minimum of six Canadians,

exclusive of the entrepreneur’s family, and that they had a

personal net worth of at least $300,000 and managerial

experience. Investors were required to have a personal net

worth of at least $500,000 and agree to invest a minimum

of $250,000 in a Canadian company for a minimum of five

years. Family-class immigrants, on the other hand, were

exempt from the points requirements. Any Canadian citizen

over 18 years of age could sponsor parents, grandparents

over the age of 60, spouses or fiances, and unmarried chil-

dren under 21, by guaranteeing 10 years of consecutive sup-

port. A subcategory in the family class was the assisted

relative, requiring five years of support and subject to certain

job-related and language qualifications. Finally, refugees

were provided for as a part of the humanitarian obligation of

the country, as defined by the 1951 United Nations Con-

vention. The cabinet was given considerable latitude in eas-

ing entrance requirements for refugees, including the

creation of categories of “displaced and persecuted” peoples

who would not be required to meet normal entrance

requirements for refugees.

See also B

ILL C

-55; C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY

AND POLICY OVERVIEW

.

Further Reading

Dirks, Gerald E. Controversy and Complexity: Canadian Immigration

Policy during the 1980s. M

ontreal: McGill–Queen’s University

Press, 1995.

Hawkins, F

r

eda. Canada and Immigr

ation: Public Policy and Public

Concern. 2d. ed. Kingston and Montreal: McGill–Queen’s Uni-

versity P

ress, 1988.

———. Critical

Years in Immigration: Canada and Australia Com-

par

ed. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1989.

Kelley

, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of C

anadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 1998.

Plaut, W. G. Refugee Status Determination in Canada: Proposals for a

New S

ystem. Hull, Canada: Canada Em

ployment and Immigra-

tion Commission, 1985.

Immigration Act (United States) (1864)

The 1864 Immigration Act was designed to increase the

flow of laborers to the United States during the disruptions

of the Civil War (1861–65). In his message to Congress in

December 1863, President Abraham Lincoln urged “the

expediency of a system for the encouragement of immigra-

tion,” noting “the great deficiency of laborers in every field

of industry, especially in agriculture and our mines.” After

much debate, Congress enacted legislation on July 4, 1864,

providing for appointment by the president of a commis-

sioner of immigration, operating under the authority of the

secretary of state, and immigrant labor contracts, up to a

maximum of one year, pledging wages against the cost of

transportation to America.

Further Reading

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: Univ

ersity of P

ennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeMay, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An A

nalysis of U.S.

Immigr

ation Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Immigration Act (United States) (1875) See P

AGE

A

CT

.

Immigration Act (United States) (1882)

Responding to dozens of petitions from states worried about

the maintenance of indigent immigrants, Congress expanded

the exclusion precedent set in the P

AGE

A

CT

of 1875.

With more than a dozen petitions filed from New York,

the principal state of disembarkation of immigrants, New

York congressmen in both houses proposed legislation for

further regulating immigration. Concerned both for the care

of recently arrived immigrants and the large financial bur-

den that states were bearing, Congress enacted the Immi-

gration Act on August 3, 1882. The measure provided for

the levying of a head tax of 50¢ per immigrant to be used

to create a Treasury-administered fund for the care of immi-

grants upon arrival, though two years later (June 16, 1884),

135IMMIGRATION ACT (UNITED STATES) (1882) 135

immigrants “coming by vessels employed exclusively in the

trade between the ports of the Dominion of Canada or the

ports of Mexico” were exempted. The 1882 act also

expanded on the Page Act exclusions of convicts and women

“imported for the purposes of prostitution” to prohibit the

immigration of any “lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to

take care of himself or herself without becoming a public

charge.” Exclusions were further expanded by an 1884 act.

Further Reading

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. P

hiladelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeMay

, M

ichael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

I

mmigration Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Immigration Act (United States) (1903)

In the wake of the assassination of President William

McKinley by anarchist Leon Czolgosz in 1901, Congress

began a thorough review of American immigration policy.

The Immigration Act provided a codification and exten-

sion of previously enacted immigration policy and

included one of the few restrictions based on political

beliefs.

In his first annual message following McKinley’s assassi-

nation, in December 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt

called for a thorough review of America’s immigration policy.

“We need,” he argued, “every honest and efficient immigrant

fitted to become an American citizen.” Roosevelt unequivo-

cally denounced anarchists, however, and urged Congress to

“exclude absolutely . . . all persons who are known to be

believers in anarchist principles.” Two days after Roosevelt’s

message, the Industrial Commission presented its findings to

Congress, including a draft bill and 18 recommendations

for the codification of immigrant policy. The bill was debated

for 14 months, with considerable disagreement over the use

of literacy tests and the proper level of the head tax. Finally

enacted on March 3, 1903, the measure

1. Reaffirmed all immigration and contract labor laws

made after 1875

136136 IMMIGRATION ACT (UNITED STATES) (1903)

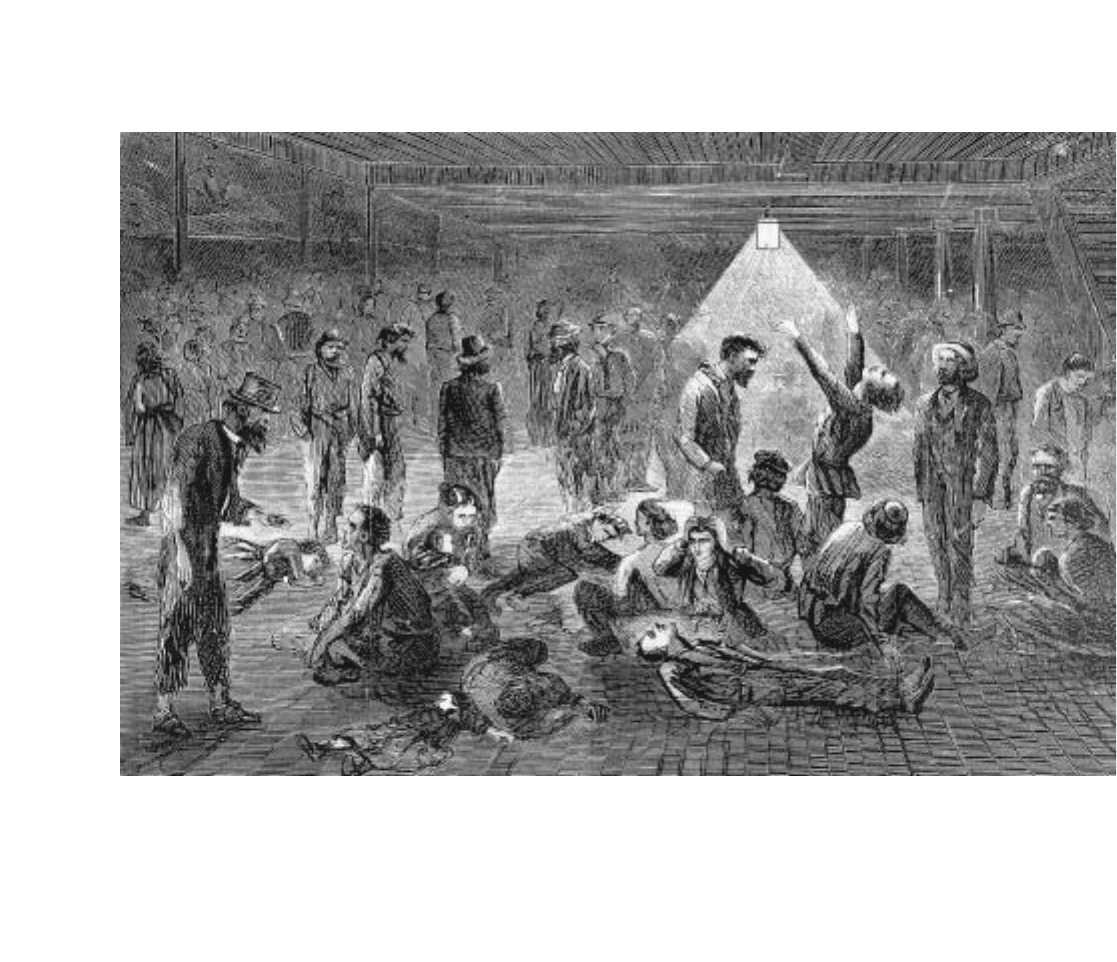

This Harper’s Weekly headline reads “Horrors of the Emigrant Ship—Scene in the hold of the ‘James Foster,’ Jun. [1869].” In

December 1863, President Abraham Lincoln encouraged Congress to pass legislation enabling potential immigrant laborers to

pledge future wages against their cost of transportation to the United States. By the 1860s, sea transportation had improved

considerably from the famine-ship era of the 1840s and 1850s. Few people died, but conditions were barely tolerable for those

who could not afford special accommodations.

(Library of Congress, Prints Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-105130])

2. Expanded excludable classes of immigrants to

include anarchists, prostitutes, epileptics, those who

had “been insane within five years,” and those who

had ever had two or more “attacks of insanity”

3. Provided for deportation within two years of arrival

of “any alien who becomes a public charge by rea-

son of lunacy, idiocy, or epilepsy,” unless he or she

could clearly demonstrate that the condition had

begun after arrival

4. Levied a head tax of $2 per immigrant

In 1907 excludable groups were expanded to include

“imbeciles, feeble-minded [persons], and persons with phys-

ical or mental defects which might affect their ability to earn

a living.”

Further Reading

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeMay, M

ichael C. F

rom Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

I

mmigration Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Immigration Act (United States) (1907)

Both the general increase in the number of immigrants and

the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901

fueled a growing

NATIVISM

in the United States and in

Congress during the first decade of the 20th century. The

Immigration Act of February 20, 1907, consolidated earlier

legislation and raised the head tax to $4 per immigrant,

excepting aliens from Canada, Newfoundland, Cuba, and

Mexico. Most notable was its creation of a commission

(D

ILLINGHAM

C

OMMISSION

) consisting of three senators,

three representatives, and three presidential appointees to

review U.S. immigration policy.

Further Reading

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeM

ay

, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

Immigration Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger

, 1987.

Immigration Act (Literacy Act) (United States)

(1917)

The Immigration A

ct of 1917, popularly known as the Lit-

eracy Act, marked a turning point in American immigration

legislation. Prohibiting entry to aliens over 16 years of age

who could not read 30–40 words in their own language, it

was the first legislation aimed at restricting, rather than reg-

ulating, European immigration. It further extended the ten-

dency toward a “white” immigration policy, creating an

“Asiatic barred zone” that prohibited entry of most Asians.

The C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

of 1882 was seen by

most policy makers as an exceptional case, but attitudes

gradually shifted with the influx of poorly educated south-

ern and eastern Europeans who arrived in the hundreds of

thousands in the 1880s. The idea of imposing a literacy test

to restrict the tide of “undesirable” Europeans was first

widely proposed by progressive economist Edward W. Bemis

in 1887. It found relatively little political support until the

cause was taken up by the I

MMIGRATION

R

ESTRICTION

L

EAGUE

, founded and supported by members of a number

of prominent Boston families. Measures incorporating a lit-

eracy test came near success in 1895, 1903, 1912, and 1915,

only to be vetoed by Presidents Grover Cleveland, Howard

Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. With the United States mov-

ing ever closer to joining the war in Europe, however, hos-

tility increased toward Germany, Ireland, and

Austria-Hungary, leading to increasing support for policies

supporting “one hundred percent Americanism.” Represen-

tative John L. Burnett of Alabama, a Democrat, revived his

bill first introduced in 1913 and vetoed by Wilson in 1915.

During debate, Senator William Paul Dillingham of Ver-

mont, a Republican and chairman of the earlier D

ILLING

-

HAM

C

OMMISSION

on immigration reform, spoke in favor

of the literacy test as more practical than a percentage plan

as a means of limiting immigration. Wilson vetoed the bill

but was overridden by both the House (287 to 106) and

the Senate (62 to 19), and the Immigration Act was formally

passed on February 5, 1917.

The main provisions of the act were heavily restrictive:

1. The head tax on immigrants was raised from $4 to

$8

2. The list of excludable aliens was consolidated and

broadened to include an Asiatic barred zone keeping

out all Asians except Japanese and Filipinos

3. Exclusion of any alien 16 or older who, if physically

capable of reading, was unable to read 30–40 words

“in ordinary use, printed in plainly legible type in

some one of the various languages or dialects” of the

immigrant’s choice

The measure was less restrictive than some had hoped but

was clear evidence of a rising nativist (see

NATIVISM

) senti-

ment and continued to reduce the number of immigrants,

which had already declined dramatically since the outbreak

of World War I in 1914.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Pol-

icy and Immigrants since 1882. New Yor

k: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative

History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeMay, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

I

mmigr

ation Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

137IMMIGRATION ACT (UNITED STATES) (1917) 137

Immigration Act (United States) (1924)

See J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

.

Immigration Act (United States) (1980)

See R

EFUGEE

A

CT

.

Immigration Act (United States) (1990)

The Immigration Act of 1990 was the first major revision

of U.S. immigration policy since the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

(1965), which had been passed in the

midst of the

COLD WAR

. The act maintained the national

commitment to reunifying families, enhanced opportunities

for business-related immigration, and made provision for

underrepresented nationalities. It also raised the annual cap

on immigration from 270,000 to 675,000 (700,000 for the

first three years).

The 1990 Immigration Act divided the immigration

preference classes into two broad categories—family spon-

sorship and employment related—and provided for annual

review of the number limits in each category. Those who

wished to restrict immigration favored the measure because

it established an annual cap on family-based immigration.

Those opposed to restriction supported the measure for its

guaranteed base of preference visas and for the raising of per-

country visas annually from 20,000 to 25,600, which

promised some relief for the backlog of applications from

Mexico and the Dominican Republic, among other coun-

tries. The measure also provided for an 18-month “Tempo-

rary Protected Status” for Salvadorans who had fled political

violence in their country during the 1980s. In fact, the mea-

sure’s caps were easily pierced, because refugees, asylees,

I

MMIGRATION

R

EFORM AND

C

ONTROL

A

CT

legalizations,

and Amerasians fell outside its provisions. Between fiscal

years 1992 and 1998, average annual immigration under the

act was just over 825,000.

Family-sponsored preferences ranged between 421,000

and 675,000 annually, depending on previous admissions.

The formula limited worldwide family sponsorships to

“480,000 minus the number of aliens who were issued visas

or adjusted to legal permanent residence in the previous fis-

cal year as 1) immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, 2) children

born subsequent to the issuance of a visa to an accompany-

ing parent, 3) children born abroad to lawful permanent res-

idents on temporary trips abroad, and 4) certain categories

of aliens paroled into the United States in the second pre-

ceding fiscal year, plus unused employment preferences in

the previous fiscal year.” The measure also established a min-

imum of 226,000 family visas per year. First preference for

admission was given to unmarried sons and daughters of

U.S. citizens and their children; second preference to

spouses, children, and unmarried sons and daughters of per-

manent resident aliens; third preference to married sons

and daughters of U.S. citizens; fourth preference to broth-

ers and sisters of U.S. citizens (at least 21 years of age).

The employment-based preference limit was set at

140,000 plus unused family preferences from the previous

year. Immigrant applications were ranked according to the

following preferences: 1) priority workers; 2) professionals

with advanced degrees or exceptional abilities; 3) skilled

workers, professionals, or unskilled workers in high demand;

4) special immigrants; and 5) investors. Per country limits

were set at 7 percent of total family and employment limits.

Finally, the Immigration Act provided for 55,000

annual “diversity immigrants,” (40,000 during the first three

years). Countries sending 50,000 immigrants during the

previous five years were ineligible to participate in the diver-

sity program. All eligible countries were divided into six

regions, and per country limits determined by a formula

including admissions during the previous five years and the

total population of the region. The annual maximum for

each country under the diversity program was 3,850.

Further Reading

Barkan, Elliott Robert. And Still They Come: Immigrants and American

Society, 1920 to the 1990s. Wheeling, I

ll.: Harlan Davidson,

1996.

Law

, Anna O. “

The Diversity Visa Lottery—a Cycle of Unintended

Consequences in United States Immigration Policy.” Journal of

American Ethnic History 21 (Summer 2002): 1–29.

Legal Immigration, Fiscal Year 2000. Office of Policy and Planning

Annual Report, No. 6. Washington, D.C.: U.S. D

epar

tment of

Justice, 2002.

Rubin, Gary E., and Judith Golub. “The Immigration Act of 1990:

An American Jewish Committee Analysis.” New York: Ameri-

can Jewish Committee Institute of Human Relations, 1990.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

(ICE)

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enfor

cement (ICE) is the

investigative arm of the Border and Transportation Security

Directorate (BTS), and it operates under the jurisdiction of

the D

EPARTMENT OF

H

OMELAND

S

ECURITY

(DHS). The

main task of ICE is to secure the nation’s borders and safe-

guard its transportation infrastructure. It employs more than

20,000 men and women to enforce laws affecting border

security and investigate homeland security crimes. There are

six operational divisions within ICE, including Air and

Marine Operations, responsible for deterring smuggling and

terrorist activity; Detention and Removal Operations,

responsible for removing deportable aliens through enforce-

ment of the nation’s immigration laws, Federal Air Marshal

Service, responsible deployment of air marshals to detect,

deter, and defeat hostile acts that target airlines; Federal Pro-

tective Service, responsible for maintaining safety at federal

government facilities; Office of Investigations, responsible

138138 IMMIGRATION ACT (UNITED STATES) (1924)

for investigating violations of immigration and custom laws

that might threaten national security; and the Office of

Intelligence, responsible for the collection, analysis, and

dissemination of data for use by ICE, BTS, and DHS.

The ICE was created as a result of the Homeland Secu-

rity Act (2002), which dissolved the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(Department of Justice), the

U.S. Customs Service (Department of the Treasury), and the

Agricultural Quarantine and Inspection program (Depart-

ment of Agriculture) and transferred security-related func-

tions to the newly created DHS as of March 1, 2003.

Further Reading

Butikofer, Nathan R. United States Land Border Security Policy: The

National S

ecurity Implications of 9/11 on the “Nation of Immi-

grants” and Free Trade in North America. Monterey, Calif.: Naval

Postgraduate School, 2003.

Gr

essle, S

haron S. Homeland Security Act of 2002: Legislative History

and P

ropagation. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Ser-

vice, 2002.

H

aynes,

Wendy. “Seeing Around Corners: Crafting the New Depart-

ment of Homeland Security.” Review of Policy Research 21, no. 3

(2004): 369–395.

U.S. I

mmigration and Customs Enforcement Web site. Available on-

line. URL: http://www.ice.gov/graphics. Accessed July 5, 2004.

Immigration and Nationality Act (United

States) (1952) See M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

A

CT

.

Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)

(United States) (1965)

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1965

mar

ked a dramatic change in American immigration policy

,

abandoning the concept of national quotas and establishing

the basis for extensive immigration from the developing

world. Technically, the various parts of the measure were

amendments to the M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

A

CT

of 1952.

The provisions of the McCarran-Walter Act allotted 85

percent of immigrant visas to countries from northern and

Western Europe. With President John F. Kennedy’s election

in fall 1960, government immigration policy began to

change. Kennedy believed that immigrants were valuable to

the country, and members of his administration argued that

both the

COLD WAR

and the Civil Rights movement dic-

tated a more open policy toward nonwhite immigrants.

Furthermore, the McCarran-Walter Act had not proven to

be as comprehensive as it had originally been intended, for

it failed to deal directly with Refugees (see

REFUGEE STA

-

TUS

), which had led to passage of the R

EFUGEE

R

ELIEF

A

CT

(1953), specifically granting asylum in the United

States to those fleeing communist persecution. Before his

assassination in 1963, Kennedy recommended that the

quota system be phased out over a five-year period, that no

country receive more than 10 percent of newly authorized

allotments, that family reunification remain a priority, that

the Asiatic Barred Zone be eliminated, and that residents of

Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago be granted nonquota sta-

tus. After the landslide victory of President Lyndon B.

Johnson in 1964, his administration was in a position to

remedy the “unworkability of the national origins quota

system.”

The major provisions of the Immigration and Nation-

ality Act included

1. Replacing national origins quotas with hemispheric

caps of 170,000 from the Eastern Hemisphere and

120,000 from the Western Hemisphere

2. Establishing a new scale of preferences, including 1)

unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens (20 per-

cent); 2) spouses and unmarried adult children of

permanent resident aliens (20 percent); 3) profes-

sionals, scientists, and artists of exceptional talent

(10 percent); 4) married children of U.S. citizens (10

percent); 5) U.S. citizens’ siblings who were more

than 21 years of age (24 percent); 6) skilled and

unskilled workers in areas where labor was needed

(10 percent); and 7) those who “because of persecu-

tion or fear of persecution . . . have fled from any

Communist or Communist-dominated country or

area, or from any country within the general area of

the Middle East” (6 percent). Unlike the provisions

of previous special legislation, these 10,200 visas

were allotted annually to deal with refugee situations

without further legislation

Although the new legislation was designed to diversify

immigration, it did so in unexpected ways. Many of the

Eastern Hemisphere slots expected to go to Europeans were

filled by Asians, who tended to fill higher preference cate-

gories. Having become permanent residents and eventually

citizens, a wide range of family members then became eligi-

ble for immigration in high-preference categories. The INA

was successful in bringing highly skilled professional and

medical people to the United States. Within 10 years, for

instance, immigrants constituted 20 percent of the nation’s

total number of physicians. At the same time, the INA was

not effective in limiting the overall number of immigrants.

Exemptions and refugees made overall immigration num-

bers larger than those permitted under the act.

Further Reading

Glazer, Nathan, ed. Clamor at the Gates: The New American Immigra-

tion. San F

rancisco: ICS Press, 1985.

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative

History of American Immigration P

olicy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

139IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT (UNITED STATES) (1965) 139

LeMay, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

Immigration Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Reimers, D

avid. Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to

America. 2d ed. N

ew York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Immigration and Naturalization Service

(INS)

From 1933 to 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization

Ser

vice (INS) was the agency of the U.S. Department of Jus-

tice responsible for enforcing immigration laws, adminis-

tering immigration benefits, and, in conjunction with the

Department of State, admitting and resettling refugees. The

INS commissioner served under the attorney general, and in

the last year of INS operation, oversaw the work of approx-

imately 29,000 employees, who served in 33 districts and 21

B

ORDER

P

ATROL

sectors along 6,000 miles of border with

Canada and Mexico.

The first commissioner of immigration was appointed

by President Abraham Lincoln under a bill enacted by

Congress (July 4, 1864) with the express purpose of

“encouraging” immigration by collecting information about

the United States and disseminating it throughout Europe.

The measure authorized immigrants to sign labor contracts

pledging up to one year of wages against transportation costs

and provided for the establishment of an emigrant office in

N

EW

Y

ORK

, N

EW

Y

ORK

. Four years later, the act was

repealed, leaving authority over immigration matters to the

states until the Immigration Act of 1891 provided clear fed-

eral control under the newly appointed Bureau of Immigra-

tion (BI). The bureau established 24 inspection stations,

including one at E

LLIS

I

SLAND

. In 1903, the BI was trans-

ferred from the Department of the Treasury to the newly

established Department of Commerce and Labor. The Nat-

uralization Act (1906) briefly extended that function to the

BI (1906–13). In a 1933 executive order, immigration and

naturalization oversight were combined under the INS. In

1940, the INS was shifted from the Department of Labor to

the Department of Justice.

During the 1990s, enforcement programs took an

increasingly larger portion of the INS budget. In 2001, 1.2

million people attempting to enter the United States illegally

were caught and turned back to either Mexico or Canada.

Greater vigilance came at a cost, however. Between 1993

and 2001, spending on enforcement programs grew more

than six times as fast as spending on other immigrant pro-

grams and services, and the total budget ballooned from

$1.52 billion to more than $5 billion. The I

LLEGAL

I

MMI

-

GRATION

R

EFORM AND

I

MMIGRANT

R

ESPONSIBILITY

A

CT

(1996) gave the INS enhanced powers of removal and

deportation, but the agency was widely criticized the fol-

lowing year for lax immigrant screening procedures. An

independent audit showed that 18 percent of approximately

1 million immigrants between August 1995 and September

1996 were admitted before criminal checks were completed,

and 71,000 were allowed to become citizens despite having

criminal records. In August 1997, a federal advisory panel

recommended abolition of the INS, with duties to be dele-

gated to other agencies, but no action was taken on the rec-

ommendation. The terrorist attacks of S

EPTEMBER

11,

2001, led by several hijackers who were in the United States

illegally, invited further criticism of the INS, provoking a

national debate on the effectiveness of the agency. Congres-

sional hearings on restructuring the INS were held in late

2001 as part of the larger national security debate. Presi-

dent George W. Bush signed the resulting Homeland Secu-

rity Act on November 25, 2002. The act abolished the INS

as of March 1, 2003, transferring its functions to various

agencies within the newly created D

EPARTMENT OF

H

OME

-

LAND

S

ECURITY

. Immigration services formerly provided by

the INS were transferred to the U.S. C

ITIZENSHIP AND

I

MMIGRATION

S

ERVICES

; enforcement oversight, to the

Border Transportation Security Directorate; border control,

to the U.S. C

USTOMS AND

B

ORDER

P

ROTECTION

; and

interior enforcement, to the U.S. I

MMIGRATION AND

C

US

-

TOMS

E

NFORCEMENT

.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Pol-

icy and Immigr

ants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Hutchinson, E. P

. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

K

urian, G

eorge T., ed. A Historical Guide to the U.S. Government. Ne

w

York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

LeMay, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

I

mmigr

ation Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Immigration and Naturalization Service v.

Chadha

(1983)

With its decision in Immigration and Naturalization Service

v. Chadha, the U.S. S

upreme Court invalidated the legisla-

tive v

eto that had enabled the U.S. Congress, in negotiation

with the executive branch, to veto certain executive actions.

The Court ruled that such agreements violated the doctrine

of separation of powers. More specifically, it determined that

one house of Congress did not have the constitutional power

to veto an I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) decision to allow a foreign student to remain in the

United States after his or her visa had expired.

The case revolved around the fate of Jagdish Chadha,

born in Kenya of Indian parents and holding a British pass-

port, who had come to the United States as a student in

1966. In 1973, he was required to “show cause why he

should not be deported,” his nonimmigrant student visa

having expired the previous year. At the deportation hear-

ing that resumed in February 1974, Chadha argued that he

140140 IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE

“had resided continuously in the United States for over

seven years, was of good moral character, and would suffer

‘extreme hardship’ if deported.” Neither Kenya, which had

become independent of British colonial rule in 1963, nor

Great Britain was willing to allow his return. Although the

INS judge ruled in Chadha’s favor and approved, through

the office of the U.S. Attorney General, his application for

permanent residency, the House of Representatives vetoed

the approval in December 1975 and the following year

ordered his deportation. Department of Justice attorneys in

the administrations of both Presidents Jimmy Carter

(1977–81) and Ronald Reagan (1981–89) joined the INS in

arguing against the constitutionality of the legislative veto.

The Court held that legislative vetoes represented a subver-

sion of the “single, finely wrought and exhaustively consid-

ered procedure” for enacting legislation. Far more than a

legal case over immigrant rights and privileges, Immigr

ation

and N

aturalization Service v. Chadha represented an impor-

tant moment in defining the extent of executiv

e and legisla-

tive power in the U.S. political system.

Further Reading

Craig, Barbara Hinkson. Chadha: The Story of an Epic Constitutional

Str

uggle. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Fisher, Louis. “Judicial Misjudgments about the Lawmaking Process:

The Legislative Veto Case.” Public Administration R

eview, Special

Issue (November 1985): 705–711.

Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

(IRPA) (Canada) (2002)

After many years of heated debate and the shock of the

S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001, terrorist attacks, in 2002 the Canadian

parliament passed the Immigration and Refugee Protection

Act (IRPA), replacing the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1976. The

measure had two general purposes: to redefine the criteria by

which immigrants would be admitted and to provide the gov-

ernment with specific tools for denying entry to potential

terrorists or deporting them once they were discovered.

The IRPA established three basic categories (family class,

economic class, refugee class) to correspond with its objec-

tives of reuniting families, contributing to economic devel-

opment, and protecting refugees. Under reunification

provisions, a Canadian citizen or permanent resident can

sponsor a spouse, common-law or conjugal partner; a depen-

dent child, including a child adopted abroad; a child under

18 to be adopted in Canada; parents or grandparents; or an

orphaned child under 18 who is a brother, sister, niece,

nephew, or grandchild and is not a spouse or common-law

partner. Two classes were established for economic immi-

grants: skilled workers and business immigrants. To be con-

sidered a skilled worker, potential immigrants had to qualify

according to a points system evaluating language, education,

and other integrative factors; must have “at least one year of

work experience within the past 10 years in a management

occupation or in an occupation normally requiring univer-

sity, college or technical training as described in the National

Occupational Classification (NOC) developed by Human

Resources Development Canada (HRDC),” and “have

enough money to support themselves and their family mem-

bers in Canada.” Business immigrants were chosen “to sup-

port the development of a strong and prosperous Canadian

economy, either through their direct investment, their

entrepreneurial activity or self-employment.” Investors were

required to have a net worth of at least $800,000, and

entrepreneurs of $300,000, along with certain levels of busi-

ness experience. Self-employed applicants were required to

demonstrate their ability to contribute at a “world-class level”

to Canada’s cultural life or athletics, or through the “purchase

and management of a farm in Canada.” The measure also

provided guidelines for admitting 20,000–30,000 refugees or

displaced persons annually.

The measure explicitly acknowledged the “shared

responsibility” of the federal government and provinces in

formulating immigration policy and established a mecha-

nism for the development and publication of federal-provin-

cial agreements regarding the number, distribution, and

settlement of permanent residents. Under these provisions,

the Canada Quebec Accord gave Quebec sole selective pow-

ers for skilled applicants and business-class immigrants and

full responsibility for integration services, while stipulating

that the federal government remained responsible for defin-

ing immigration categories, determining inadmissibility, and

enforcement. As a result of frequent abuses of the 1976 sys-

tem, the new act required careful monitoring of the immi-

grant flow; an annual report projecting the number of

foreign nationals who might become permanent residents in

the following year, the number of permanent residents in

each class in provinces that have responsibility for selection

under a federal-provincial agreement, the linguistic profile

of new permanent residents, and the number of people

granted permanent residence on humanitarian grounds; and

a gender-based analysis of the immigration program. The act

also established the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB)

as an independent, quasi-judicial administrative tribunal

with a mandate “to make well-reasoned decisions on immi-

gration and refugee matters efficiently, fairly and in accor-

dance with the law.”

The second major purpose of the Immigration and

Refugee Protection Act was to protect Canada against poten-

tially hostile immigrants. The act provided that after enact-

ment of the measure on June 28, 2002, all new permanent

residents would receive permanent resident cards, which they

could apply for after October 15, 2002, and that effective

January 2004, the cards would be required for reentry of per-

manent residents who had traveled outside Canada. The act

also provided for the removal of anyone involved in “orga-

nized crime, espionage, acts of subversion, terrorism, war

141IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEE PROTECTION ACT 141

crimes, human or international rights violations, criminality

and serious criminality.” In addition, the measure made it

easier for immigration officials to detain people on “reason-

able suspicion” of failing to appear for possible deportation

proceedings, of posing a risk to the public, or of refusing to

give information to the immigration service.

Further Reading

Hillmer, Norman, and Maureen Appel Molot, eds. Canada among

Nations, 2002: A F

ading Power. New York: Oxford University

Pr

ess, 2003.

“Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The Act and Regulations:

Key Reference Material.” Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

Available online. URL: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/irpa/key-

ref.html. Accessed January 16, 2004.

“Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.” Part I. Canada

G

azette 135, no. 50 (December 15, 2001): 4,476–4,800.

“I

mmigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.” Part I. Canada

Gaz

ette 136, no. 10 (March 9, 2002): 558–621.

Ma

rrocco, Frank N., and Henry M. Goslett. 2004 Annotated Immi-

gr

ation Act of Canada. Toronto: Thomson Carswell, 2003.

Immigration Appeal Board Act (Canada)

(1967)

Follo

wing a broad government reorganization of the immi-

gration bureaucracy in Canada, the Immigration Appeal

Board Act was passed, creating the Immigration Appeal

Board. It provided the first independent review process of all

official decisions regarding deportation and family-spon-

sored application denials, guaranteeing immigrants due pro-

cess protections.

Following the Liberal Party’s return to power in 1963, a

full review of immigration procedures was undertaken, lead-

ing to a massive reorganization of governmental agencies and

policies, including the Government Organization Act (1966),

the

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

of 1967, and the Immigra-

tion and Appeal Board Act. After another Liberal-sponsored

study, in 1966, the D

EPARTMENT OF

M

ANPOWER AND

I

MMIGRATION

issued a white paper recommending greater

emphasis on economic need and less on family sponsorship.

With the combination of greater selectivity, the right to apply

for landed immigrant status while in the country, and guar-

anteed review of deportation cases, the backlog of cases before

the board grew dramatically. By 1973, Minister of Manpower

and Immigration Robert Andras reported that “many per-

sons who appealed a deportation order could count on a 20-

year stay in Canada while awaiting the outcome.” In order to

solve the problem, an amendment to the act was passed in

1973, abolishing the automatic right of appeal while provid-

ing amnesty for those who registered within 60 days. The revi-

sions were supported across the political spectrum and led to

39,000 immigrants from more than 150 countries being

granted landed immigrant status.

Further Reading

Hawkins, Freda. Canada and Immigr

ation. 2d ed. Kingston and Mon-

treal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1989.

———. Critical Years in Immigration: Canada and Australia Com-

par

ed. K

ingston and Montr

eal: McGill–Queen’s University Press,

1989.

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

Histor

y of C

anadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 2000.

Immigration Marriage Fraud Amendments

(United States) (1986, 1990)

Amending the M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

A

CT

(1952), the Immigration Marriage

Fraud Amendments of 1986 specified a two-year residency

requirement for alien spouses and children before obtaining

permanent resident status. By provisions of the amendment,

a couple is required to apply for permanent status within

90 days of the end of the conditional two-year period. The

Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) could then

interview the couple in order to satisfy themselves that 1) the

marriage was not arranged “for the purpose of procuring an

alien’s entry as an immigrant, 2) the marriage was still legally

valid, and 3) a fee was not paid for the filing of the alien’s

petition. Punitively, the amendment made such marriage

fraud punishable by up to five years in prison and $250,000

in fines, further grounds for deportation, and a permanent

bar to future applications. The amendment also required

that aliens contracting marriages after the beginning of

deportation proceedings live two years outside the United

States before becoming eligible for permanent resident sta-

tus. A related amendment of 1990 allowed for exemptions

in the case of wife or child battering, or if clear evidence

could be presented to show that the marriage was contracted

in good faith and not for the purpose of gaining residency.

See also

PICTURE BRIDES

.

Further Reading

Cordasco, Francesco. The New American Immigration. New York: Gar-

land, 1987.

LeM

ay, Michael C. Anatomy of a Public Policy: The Reform of Contem-

porary American Im

m

igration Law. Westport, Conn.: Praeger,

1994.

R

eimers, D

avid. Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to

America. 2d ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Immigration Reform and Control Act

(IRCA) (United States) (1986)

In the wake of massive refugee crises in Southeast Asia and

Cuba (see

REFUGEE STATUS

), in 1981, a Select Commission

on Immigration and Refugee Policy recommended to the

U.S. Congress that undocumented aliens be granted

amnesty and that sanctions be imposed on employers who

142142 IMMIGRATION APPEAL BOARD ACT

hired undocumented workers. After years of heated debate

involving ethnic and religious groups, labor and agricul-

tural organizations, business interests, and the government,

a compromise measure was reached. The Immigration

Reform and Control Act (IRCA) provided amnesty to

undocumented aliens continuously resident in the United

States, except for “brief, casual, and innocent” absences,

from the beginning of 1982; provided amnesty to seasonal

agricultural workers employed at least 90 days during the

year preceding May 1986; required all amnesty applicants to

take courses in English and American government to qualify

for permanent residence; imposed sanctions on employers

who knowingly hired illegal aliens, including civil fines and

criminal penalties up to $3,000 and six months in jail; pro-

hibited employers from discrimination on the basis of

national origins; increased border patrol by 50 percent in

1987 and 1988; and, in a matter unrelated to illegal aliens,

introduced a lottery program for 5,000 visas for countries

“adversely affected” by provisions of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965.

Because the measure was meant as a one-time resolution

of a longstanding problem, a strict deadline for application

was established: All applications for legalization were

required within one year of May 5, 1987. At the insistence

of state governments, newly legalized aliens were prohibited

from receiving most types of federal public welfare, although

Cubans (see C

UBAN IMMIGRATION

) and Haitians (see

H

AITIAN IMMIGRATION

) were exempted. By the end of the

filing period, about 1.7 million people had applied for gen-

eral legalization, and about 1.4 million as special agricultural

workers. Of the successful applicants, almost 70 percent

were from Mexico and more than 90 percent from the West-

ern Hemisphere. The measure was not highly effective in

curbing employment of illegal aliens, as officials were pro-

hibited from interfering with workers in the field without a

search warrant.

Further Reading

Bean, Frank D., Georges V

ernez, and Charles B. Keely. Opening and

Closing the Doors: Evaluating Immigration Reform and Control.

Washington, D.C.: Rand Corporation and the Urban Institute,

1989.

Espenshade, Thomas, et al. “I

mmigration P

olicy in the United States:

Future Prospects for the Immigration Reform and Control Act of

1986.” In Population Policy: Contemporary Issues. Ed. Godfrey

Roberts. N

ew York: Praeger, 1990.

Gonzalez-Baker, Susan. “The ‘Amnesty’ Aftermath: Current Policy

Issues Stemming from the Legalization Programs of the 1986

Immigration Reform and Control Act.” International Migration

Review 31 (1997): 5–27.

Laham, Nicholas. Ronald Reagan and the Politics of Immigration

R

eforms. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2000.

LeMay, Michael C. Anatomy of a Public Policy: The R

efor

m of Contem-

porary American Immigration Law. Westport, Conn.: Praeger,

1994.

Meissner, D., D. P

apademetrious, and D. North. Legalization of

Undocumented A

liens: Lessons from Other Countries. Washington,

D.C.: Carnegie Endo

wment for International Peace, 1986.

Reimers, David. Still the G

olden Door: The Third World Comes to

A

merica. 2d ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Rivera-B

atiz, Francisco, Selig L. Schzer, and Ira N. Gang, eds. U.S.

Immigration

Policy Reform in the 1980s: A Preliminary Assess-

ment. New York: Praeger, 1991.

V

erne

z, Georges, ed. Immigration and International Relations: Pro-

ceedings of a Conference on the I

nternational Effects of the 1986

Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). Washington, D.C.:

U

rban I

nstitute, 1989.

Immigration Reform Act See I

LLEGAL

I

MMIGRA

-

TION

R

EFORM AND

I

MMIGRANT

R

ESPONSIBILITY

A

CT

.

immigration regulations (Canada) (1967)

In the wake of the White Paper on Canadian Immigration

Policy of October 1966, the Canadian government

announced a new series of immigration regulations in

September 1967. Although designed in large measure to sys-

tematically address the almost unregulated movement of

sponsored Canadian immigrants, the regulations introduced

for the first time the principle of nondiscrimination on the

basis of race or national origin, virtually ending the White

Canada policy that had prevailed since the beginning of the

20th century.

Following the Liberal return to power in 1963,

widespread concern over the massive influx of family-spon-

sored, often unskilled immigrants led to a full review of

immigration procedures, leading to a massive reorganiza-

tion of governmental agencies and policies, including the

Government Organization Act (1966), the Immigration

Appeal Board Act (1967), and the immigration regulations

of 1967. The new regulations created three categories of

immigrants: independent, sponsored, and nominated. The

admission of independent applicants was determined by a

new Norms of Assessment point system, applied in nine

categories: education, age, suggesting long-term suitability,

fluency in English or French, employment opportunities,

Canadian relatives, area of destination, occupational

demand, and occupational skill. Close family relatives were

admitted as sponsored immigrants, but more distant “nom-

inated” relatives were subject to a points evaluation on the

basis of education, personal characteristics, job skills, job

demand, and age. Section 34 of the new regulations also

enabled aliens to apply for immigrant status after arriving

in Canada. The new regulations were generally welcomed as

a fairer method of determining eligibility. By the early

1970s, however, it became clear that immigrants were tak-

ing advantage of the new appeals policy, leading to a mas-

sive backlog of appeals and further impetus for the more

143IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS 143