Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 7 Predation, grazing and disease

249

Predation, true predators, grazers and parasites

A predator may be defined as any organism that con-

sumes all or part of another living organism (its ‘prey’

or ‘host’) thereby benefiting itself, but, under at least

some circumstances, reducing the growth, fecundity

or survival of the prey.

‘True’ predators invariably kill their prey and do so

more or less immediately after attacking them, and

consume several or many prey items in the course

of their life. Grazers also attack several or many prey

items in the course of their life, but consume only part

of each prey item and do not usually kill their prey.

Parasites also consume only part of each host, and

also do not usually kill their host, especially in the short

term, but attack one or very few hosts in the course

of their life, with which they therefore often form a

relatively intimate association.

The subtleties of predation

Grazers and parasites, in particular, often exert their

harm not by killing their prey immediately like true

predators, but by making the prey more vulnerable

to some other form of mortality.

The effects of grazers and parasites on the organ-

isms they attack are often less profound than they first

seem because individual plants can compensate for

the effects of herbivory and hosts may have defensive

responses to attack by parasites.

The effects of predation on a population of prey

are complex to predict because the surviving prey

may experience reduced competition for a limiting

resource, or produce more offspring, or other pre-

dators may take fewer of the prey.

Predator behavior

True predators and grazers typically ‘forage’, moving

around within their habitat in search of their prey. Other

predators ‘sit and wait’ for their prey, though almost

always in a selected location. With parasites and

pathogens there may be direct transmission between

infectious and uninfected hosts, or contact between

free-living stages of the parasite and uninfected hosts

may be important.

Optimal foraging theory aims to understand why

particular patterns of foraging behavior have been

favored by natural selection (because they give rise

to the highest net rate of energy intake).

Generalist predators spend relatively little time

searching but include relatively low-profitability items

in their diet. Specialists only include high-profitability

items in their diet but spend a relatively large amount

of their time searching for them.

Population dynamics of predation

There is an underlying tendency for predators and

prey to exhibit cycles in abundance, and cycles are

observed in some predator–prey and host–parasite

interactions. However, there are many important

factors that can modify or override the tendency to

cycle.

Crowding of either predator or prey is likely to have

a damping effect on any predator–prey cycles.

Many populations of predators and prey exist as a

‘metapopulation’. In theory, and in practice, asynchrony

in population dynamics in different patches and the

process of dispersal tend to dampen any underlying

population cycles.

Predation and community structure

There are many situations where predation may hold

down the densities of populations, so that resources

are not limiting and individuals do not compete for

them. When predation promotes the coexistence of

species amongst which there would otherwise be

competitive exclusion (because the densities of some

or all of the species are reduced to levels at which

competition is relatively unimportant) this is known as

‘predator-mediated coexistence’.

The effects of predation generally on a group of

competing species depend on which species suffers

most. If it is a subordinate species, then this may be

driven to extinction and the total number of species

in the community will decline. If it is the competitive

dominants that suffer most, however, the results of

heavy predation will usually be to free space and

resources for other species, and species numbers

may then increase.

It is not unusual for the number of species in a

community to be greatest at intermediate levels of

predation.

SUMMARY

Summary

9781405156585_4_007.qxd 11/5/07 14:53 Page 249

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

250

REVIEW QUESTIONS

Review questions

Asterisks indicate challenge questions

1 With the aid of examples, explain the feeding

characteristics of true predators, grazers,

parasites and parasitoids.

2* True predators, grazers and parasites can alter

the outcome of competitive interactions that

involve their ‘prey’ populations: discuss this

assertion using one example from each

category.

3 Discuss the various ways that plants may

‘compensate’ for the effects of herbivory.

4 Predation is ‘bad’ for the prey that get eaten.

Explain why it may be good for those that do

not get eaten.

5* Discuss the pros and cons, in energetic

terms, of (i) being a generalist as opposed

to a specialist predator, and (ii) being a

sit-and-wait predator as opposed to an

active forager.

6 In simple terms, explain why there is an

underlying tendency for populations of

predators and prey to cycle.

7* You have data that shows cycles in nature

among interacting populations of a true

predator, a grazer and a plant. Describe an

experimental protocol to determine whether this

is a grazer–plant cycle or a predator–grazer

cycle.

8 Define mutual interference and give examples

for true predators and parasites. Explain how

mutual interference may dampen inherent

population cycles.

9 Discuss the evidence presented in this chapter

that suggests environmental patchiness has

an important influence on predator–prey

population dynamics.

10 With the help of an example, explain why most

prey species may be found in communities

subject to an intermediate intensity of predation.

9781405156585_4_007.qxd 11/5/07 14:53 Page 250

251

Chapter 8

Evolutionary ecology

CHAPTER CONTENTS

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Molecular ecology: differentiation within and between species

8.3 Coevolutionary arms races

8.4 Mutualistic interactions

Chapter contents

KEY CONCEPTS

In this chapter you will:

l

appreciate the range of molecular (DNA) markers that have been used

in ecology

l

understand how these markers can be put to work in determining the

extent of subdivision within, and the degree of separation between,

species

l

recognize the importance of coevolutionary arms races in the

dynamics of the component populations, especially of plants

and their insect herbivores, and of parasites and their hosts

l

understand the nature of mutualistic interactions in general and their

crucial importance both for the species concerned and for almost all

communities on the planet

l

appreciate the particular contributions of mutualisms in diverse

areas from farming, through the functioning of guts and roots, to

the fixation of nitrogen by plants

Key concepts

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 251

8.1 Introduction

In Chapter 2, we set the scene for the remainder of this book by illustrating

how, to modify slightly Dobzhansky’s famous phrase, ‘nothing in ecology makes

sense, except in the light of evolution’. But evolution does more than underpin

ecology (and the whole of the rest of biology). There are many areas in ecology

where evolutionary adaptation by natural selection takes center stage to the extent

that the term ‘evolutionary ecology’ is often used to describe them. In several

previous chapters, therefore, topics in evolutionary ecology have been dealt with,

quite naturally, as integral parts of broader ecological questions. In Chapter 3,

we examined the nature and importance of defenses that have evolved to protect

plants and prey from their predators. In Chapter 5, we saw how patterns in life

histories – schedules of growth, reproduction and so on – can only be understood

in relation to corresponding patterns in the habitats in which they have evolved.

In Chapter 6, we looked at interspecific competition as an evolutionary driving

force, generating patterns in the coexistence and exclusion of competing species.

And in Chapter 7, we discussed ‘optimal foraging’: the evolution of behavioral

strategies that maximize predator fitness and thus mold their dynamic interactions

with their prey.

This, of course, is not an exhaustive survey of topics in evolutionary ecology.

In the present chapter, therefore, we deal with a number of others (though the

final list will remain less than exhaustive). We focus especially on coevolution:

pairs of species acting as reciprocal driving forces in one another’s evolution. The

question of coevolutionary ‘arms races’ between predators and their prey is taken

up in Section 8.3, with a particular emphasis on host–pathogen interactions: each

adaptation in the prey that fends off or avoids the attacks of a predator provoking

a corresponding adaptation in the predator that improves its ability to overcome

those defenses. However, not all coevolutionary interactions are antagonistic.

Many species-pairs are ‘mutualists’: both parties benefiting, on balance at least,

from the interactions in which they take part. Some of the most important of

these mutualisms – pollination, corals and nitrogen fixation, for example – are

discussed in Section 8.4. We begin, though, not with species interactions but with

aspects of evolutionary differentiation within and between species, especially

those detectable by modern techniques developed in molecular genetics and thus

often described as aspects of ‘molecular ecology’.

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

252

We have noted previously that nothing in ecology makes sense, except in the light

of evolution. But some areas of ecology are even more evolutionary than others.

We may need to look within individuals to examine the details of the genes

they carry, or to acknowledge explicitly the crucial and reciprocal role that

species play in one another’s evolution.

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 252

8.2 Molecular ecology: differentiation within

and between species

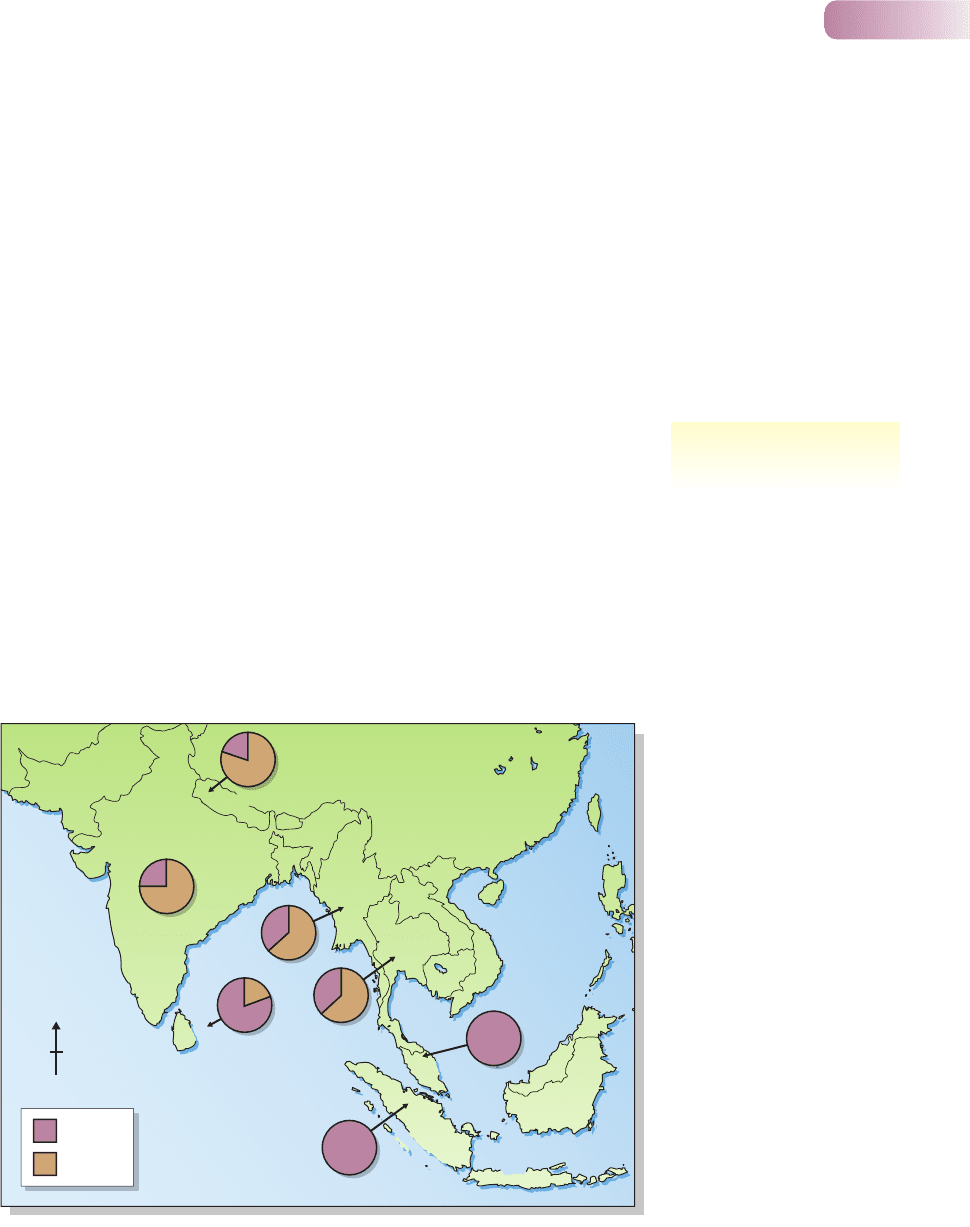

For much of the time, it is entirely appropriate for ecologists to talk about

‘populations’ or ‘species’ as if they were singular, homogeneous entities: for

example, we may talk of ‘the distribution of Asian elephants’, saying nothing

about whether the species might be differentiated into distinct races or subgroups,

as indeed it is (Figure 8.1). But for some purposes, knowing how much differ-

entiation there is within species, or between one species and another, is critical

for an understanding of their dynamics, and ultimately for managing those

dynamics. Is a particular population derived largely from offspring born locally,

or from immigrants from another, distinguishable population? Where exactly

does the distribution of a particular species end and that of another, closely related

species begin? In cases like these, being able to determine, at a variety of scales,

who is most closely related to whom (and who is quite distinct from whom) may

be essential.

Our ability to do this itself depends on the resolution with which we can

differentiate individuals from one another and even determine where they came

from or who their parents were. In the past, this was difficult and frequently

impossible: reliance on simple, visual markers meant that all individuals within

a species often looked the same, and even members of closely related species

could often only be distinguished by experienced taxonomists looking down a

microscope at, say, details of a male’s genitalia. Now, though, molecular, genetic

markers (albeit still requiring experts and expensive equipment) have massively

Chapter 8 Evolutionary ecology

253

N

India

Arabian

Sea

Indian

Ocean

Sri

Lanka

Nepal

Clade A

Clade B

China

Myanmar

Thailand

Malaysia

Indonesia

(Sumatra)

Java

Figure 8.1

Distribution of two distinct ‘clades’ of

the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus

(groups with distinct evolutionary

histories following their common

origin), revealed only by an analysis

of molecular markers. These ciades

coexist in many areas, though their

distinctiveness itself suggests a

degree of independence in their

dynamics even when they do coexist.

AFTER FLEISCHER ET AL., 2001

the need to know who is most

closely related to whom

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 253

increased the resolution at which we can differentiate between populations and

even between individuals, and hence have vastly improved our ability to address

these types of questions. We begin, therefore, in Box 8.1, with a brief survey of

some of the most important of these molecular markers and their uses.

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

254

8.1 QUANTITATIVE ASPECTS

8.1 Quantitative aspects

This is not the place for crash courses in either

molecular biology or the laboratory methods used

to extract, amplify, separate and analyze molecular

markers, but it will nonetheless be useful to have

some appreciation of their nature and key properties

– and to be introduced to some of the technical terms

and abbreviations that abound in this area. Most

recent studies in ecology have used DNA of one type

or other for molecular identification. We need, at

the very least, to be aware that a length of DNA is

characterized by the sequence of bases of which it

is composed, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G)

and thymine (T), and that in double-stranded DNA,

these link across to one another in complementary

base-pairs: A-T and G-C.

Choosing a molecular marker

The basis for all uses of molecular markers in eco-

logy is that individuals can be differentiated from

one another to greater or lesser extents as a result

of molecular variation amongst them. The ultimate

source of this variation is mutation in the sequence

of bases, which, of course, occurs independently of

its consequences for the organism concerned. What

happens to the mutation, and the mutated organism,

then depends essentially on the balance between

selection and ‘genetic drift’ (random, undirected

changes in gene frequency from generation to gener-

ation). If the mutation occurs in a region of DNA that

is important because, say, it codes for a crucial part of

an essential enzyme, then selection is likely to deter-

mine the outcome. An unfavorable mutation (the vast

majority in important regions of DNA) will quickly be

lost because the mutated organism is less fit than its

counterparts. Individuals will therefore differ relatively

little in such regions, and if they do, differentiation is

most likely to reflect ‘adaptive’ variation: different vari-

ants being favored in different individuals, perhaps

because of where they live.

But there are also regions of DNA that appear not

to code for important parts of enzymes or to per-

form any other function where the precise sequence

is crucial. Variation in these regions is therefore said

to be ‘neutral’, and mutations can accumulate there

over time. Imagine two offspring of a single mating.

They will be genetically very similar. But imagine now

that each, literally, goes its own way. As each gener-

ation passes and mutations accumulate, the lineages

derived from them will become increasingly divergent

in those regions of their genome where variation is

neutral, and lineages derived from those lineages

will diverge in their turn. A snapshot taken in the

future should allow us to determine, broadly, who has

diverged most recently, and which groups have barely

diverged at all, though our ability to do this will itself

depend on the rate of mutation in the DNA region

concerned: too slow and individuals will tend all to

look the same; too fast and each individual sampled

will tend to be so unique that its relationships to

others will be hard to discern. Molecular markers are

therefore chosen, ideally, such that the mutation rate

matches the question being addressed. A study of

differentiation between gerbils living in different

burrow systems in the same, local population should

use a region of DNA where the mutation rate is high

(much divergence from generation to generation);

whereas a study tracing the routes of colonization that

have placed different populations of brown bears

Molecular markers

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 254

Chapter 8 Evolutionary ecology

255

over the whole of Europe in the 10,000–12,000 years

since the last glaciation should use a region where

the mutation rate is relatively low.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

As a practical point, most studies in molecular eco-

logy, having extracted the DNA from the organism

concerned, use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

to amplify the amount of target material such there is

sufficient available for analysis. By therefore being able

to make use of small samples, this has revolutionized

our ability to sample individuals ‘non-invasively’, using

blood, hair, feces or wing clips. Very simply, PCR

requires ‘primers’ that flank the particular sequence

of DNA that is to be amplified. In the PCR reaction,

nowadays fully automated, the originally double-

stranded DNA is denatured to single strands, the

primers anneal to the separated strands, and an

enzyme, DNA polymerase, copies the sequence

between the primers. This series of reactions is then

repeated 30–40 times, and, since the process of

repeated amplification is exponential, an originally

small amount of target DNA in the midst of other,

unwanted sequences becomes a large enough amount

of target to be subjected to analysis. Note, though,

that hidden within this brief description is the need to

have identified not only informative target regions of

DNA, but also the primers that characterize them.

Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA

In the past especially, many studies have used not

nuclear DNA (inherited equally from both parents and

holding the code for the vast majority of an organism’s

functions) but the relatively small lengths of mito-

chondrial DNA (mtDNA), found in the mitochondria in

the cytoplasm of each of an organism’s cells. The

main advantages of mtDNA are that, almost always, it

is inherited only from the mother (who contributes the

cytoplasm to the fused egg) and does not undergo

recombination. Thus, lineages can be more clearly

traced from generation to generation. Also, the muta-

tion rate is higher than for coding regions of nuclear

DNA, allowing finer resolution differentiation. On the

other hand, mtDNA offers only a small number of

targets, and its maternal inheritance means that when

disparate types meet in a population it is impossible

to know whether any individuals are the result of

matings between them. Increasingly, therefore, studies

are focusing on regions of nuclear DNA, though often

in parallel with analyses of mtDNA genes, combining

the advantages of both.

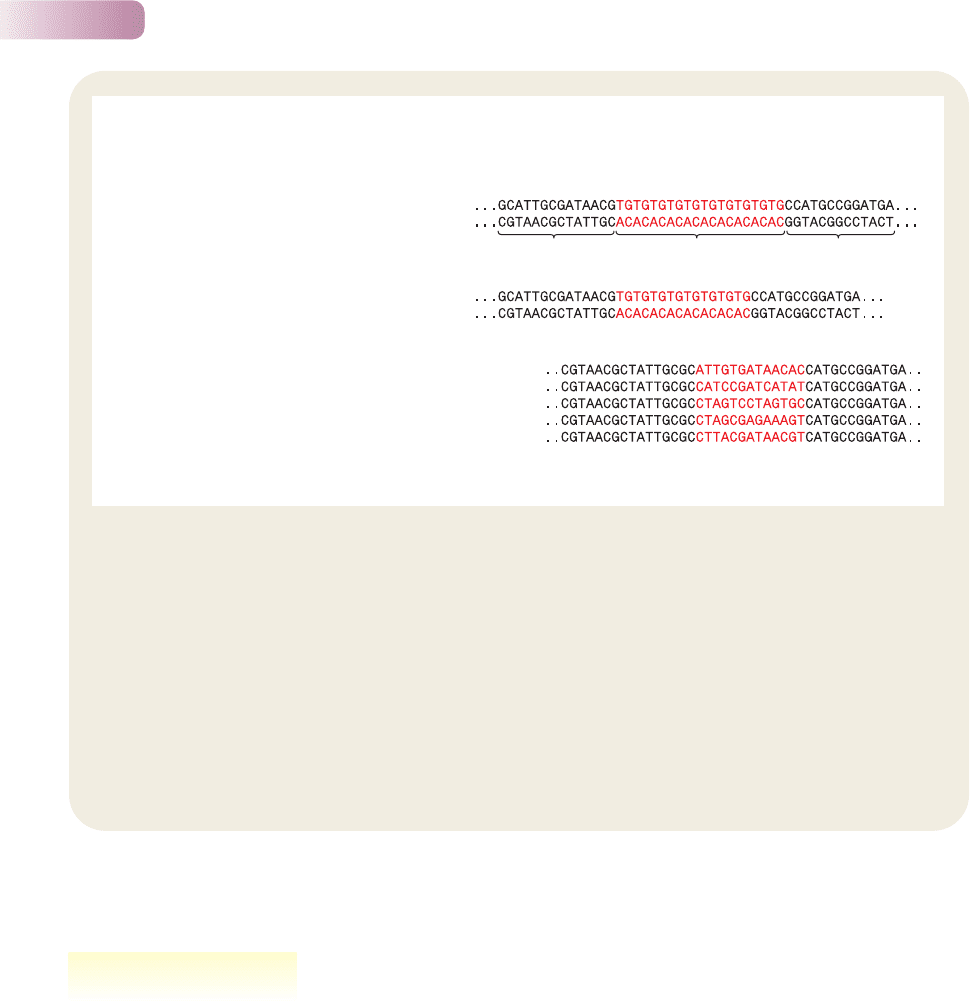

Microsatellites

Within the nuclear genome, sequences coding for

proteins (i.e. genes) are by no means the only regions

that have been utilized by molecular biologists. Micro-

satellites, for example, are regions of DNA in which

the same two, three of four bases are repeated many

times, preceded and followed in the sequence by

flanking regions that uniquely identify each micro-

satellite (Figure 8.2a). The variability comes from the

fact that the number of ‘repeats’ can vary, the result-

ing lengths of microsatellite DNA being measured by

the speed at which they move through a semisolid

medium (a ‘gel’) under the influence of an electric

current (electrophoresis). Microsatellites may be highly

polymorphic within a population. Thus, an appropriately

chosen ‘panel’ of microsatellites for a species may

effectively allow each individual in a population to be

uniquely identified (a DNA ‘fingerprint’), making micro-

satellites especially appropriate at the finer scales of

differentiation.

Sequencing

As far as nuclear or mitochondrial genes are con-

cerned, having chosen, extracted and amplified

the target region from a sample of individuals, it is

necessary to have some basis for differentiating indi-

viduals from one another, determining who is most

similar to whom, and so on. Increasingly, as automa-

tion improves, and costs come down, the whole

sequences of genes are being determined. As previ-

ously noted, regions of the same gene differ in terms

of their functional importance (Figure 8.2b). Some

regions are ‘conserved’ from individual to individual,

from population to population, and often from species

to species. These are (or are presumed to be) the

regions of greatest functional importance, and they

play effectively no part in differentiation. But there are

other regions where far more variation is observed

(and that can be presumed, therefore, to be neutral

or at least subject to weaker selective constraints),

and it is on the basis of this that individuals and

populations can be differentiated.

s

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 255

8.2.1 Differentiation within species

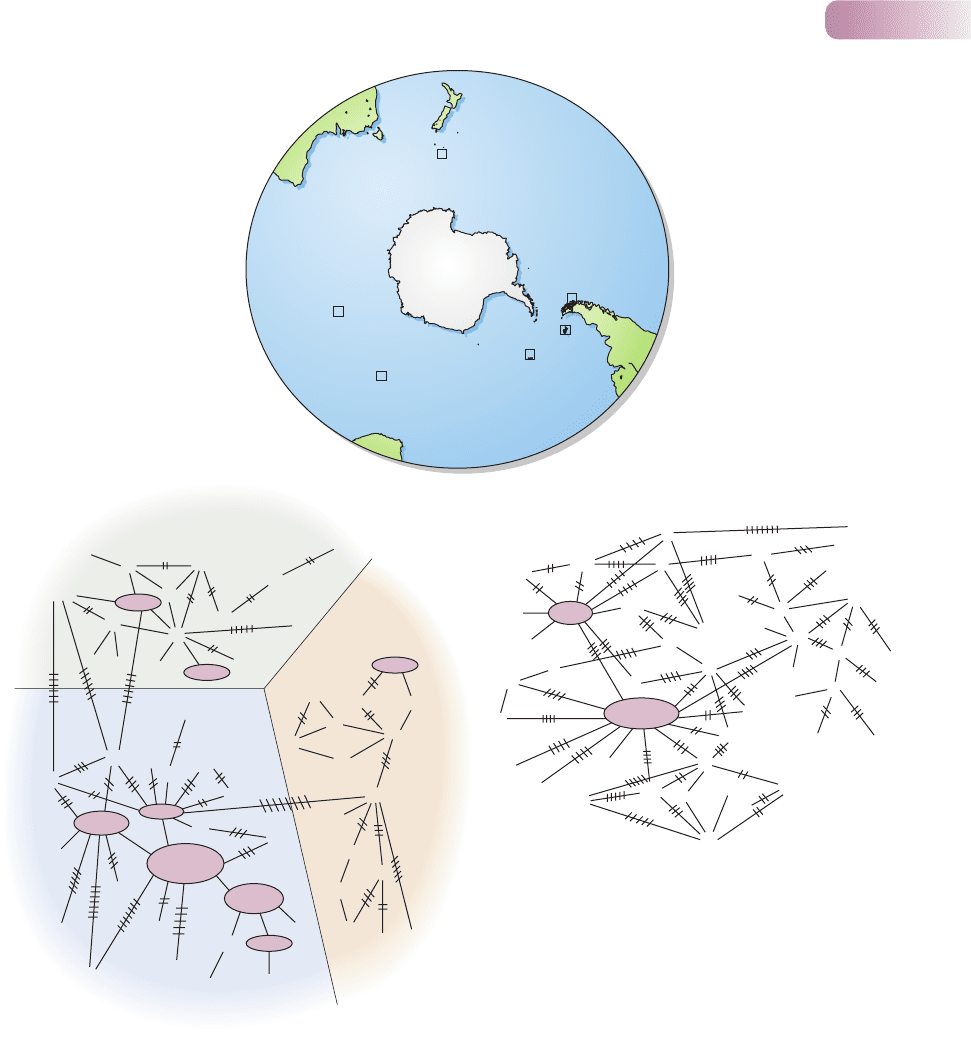

Albatrosses, wide ranging sea birds with the largest wingspans of any birds alive

today, have achieved iconic status by virtue of their appearance in poems and

stories, but of the 21 species normally recognized, 19 are regarded as ‘threatened’

with extinction and the other two as ‘near threatened’. The black-browed

albatross has recently been split by taxonomists into two species: Thalassarche

impavida, found only on Campbell Island, between New Zealand and Antarctica,

and T. melanophris, with breeding populations elsewhere in the sub-Antarctic,

including the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and Chile (Figure 8.3a). The

gray-headed albatross, T. chrysostoma, similar in size, also breeds on a number of

sub-Antarctic islands, including South Georgia. The black-browed species usu-

ally remain associated with coastal shelf systems, whereas gray-headed albatrosses

are far more ‘oceanic’ in their feeding grounds, but both, like all albatross species,

are thought to return very close to their place of birth to breed (natal philopatry).

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

256

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

(RFLP)

However, in the past especially, use was often made

of ‘restriction endonuclease’ enzymes that cut DNA

at specific recognition sites situated along its length

and so split an original strand of DNA into fragments.

Individuals differ, as a result of largely neutral muta-

tions, in the location of these sites, and so they

differ, too, in the lengths of the fragments generated,

these lengths being monitored by electrophoresis.

This variation, within a population, is known as

restriction fragment length polymorphism, RFLP,

and there are therefore separate polymorphisms for

different restriction enzymes (because their recogni-

tion sites differ). Samples can thus be subjected

in turn to a series of enzymes, and the most differ-

entiated individuals will then differ in the greatest

number of RFLPs. Its disadvantage, of course, is that

it utilizes only a small part of the underlying sequence

variation.

s

Allele 1 which has 10 repeats

(b)

Allele 2 which has 8 repeats

Individual 1

Individual 2

Individual 3

Individual 4

Individual 5

(a)

Flanking region Flanking regionMicrosatellite

Figure 8.2

(a) A ‘locus’, here, refers to the location of a region in

the overall DNA sequence. An ‘allele’ is the particular

variant of sequence that exists at that locus in a

particular case. Remember that that sequence is of

two strands of DNA, between which the bases are

paired: G with C and A with T. This figure shows two

contrasting alleles at a microsatellite locus, with its

sequence of repeated bases (of differing length)

in the two DNA strands (red) and exactly similar

flanking regions at either end (black). (b) This figure,

by contrast, shows the base sequence in just one

DNA strand of a hypothetical gene (i.e. a sequence of

DNA coding for a protein) from five individuals. Note

the contrast between the conserved (unvarying)

regions at either end, in black, and a variable region

in red towards the center. Differentiation between

individuals clearly depends on this variable region.

albatrosses

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 256

Chapter 8 Evolutionary ecology

257

(a)

(b)

(c)

T. impavida

T. melanophris

(Falkland)

T. melanophris

(Diego/South Georgia/Kerguelen)

DR

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

FI

E

F

mC

mC

mC

mC

mC

mC

mC

mC

A

A

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

BI

B

D

K

K

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

DR

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

H

G

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

iC

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

B

Campbell Is.

Kerguelen Is.

Marion Is.

Falkland Is.

South Georgia

Diego Ramirez

Antarctica

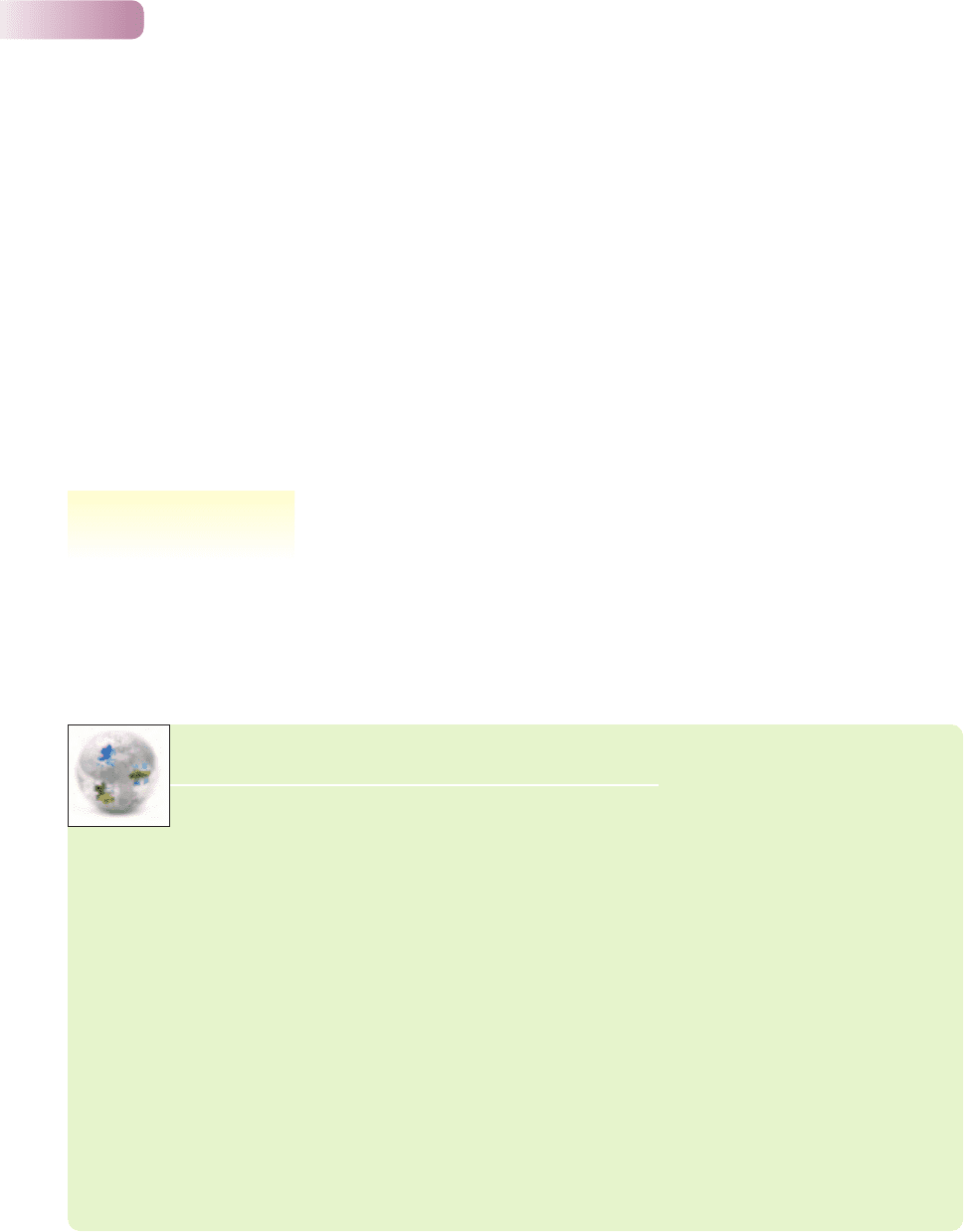

Figure 8.3

Population differentiation in albatrosses: black-browed albatrosses, Thalassarche melanophris and T. impavida, and the gray-headed albatross,

T. chrysostoma. (a) Distribution of sites in the sub-Antarctic from which samples were taken. (b) The relationships amongst 73 black-browed

albatrosses in the base sequence at a focal, variable site in their mtDNA. Where individuals from the same site shared exactly the same sequence,

those individuals have been assigned a letter code (A, B, etc.) and placed in an oval proportional in size to the number of individuals. Individuals that

do not fall into these groups, having a sequence unique within the data set, are identified as follows: BI, South Georgia, DR, Diego Ramirez (Chile),

FI, Falkland Islands, K, Kerguelen Island (all T. melanophris); mC, T. melanophris from Campbell Island; and iC, T. impavida from Campbell Island.

The cross-hatches represent the number of base differences between the individuals (or groups) they join. The samples fall into three ‘clusters’:

T. impavida, T. melanophris from the Falkland Islands and T. melanophris from all other sites. Note though that the clustering is not perfect – as is

normal, like the separation between the populations – and that some of the T. melanophris found on Campbell Island were identifiable as T.

melanophris–T. impavida hybrids. (c) The relationships amongst 50 gray-headed albatrosses in the base sequence at a focal, variable site in their

mtDNA. Coding is the same as in (b) except that M is Marion Island and C is Campbell Island. No separate clusters are discernable in this case.

AFTER BURG & CROXALL, 2001

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 257

With numbers in all sites declining year on year, therefore, the questions arise:

‘How connected or separate are these populations? Should conservation efforts

be directed at what are currently perceived to be whole species, or at particular

breeding populations?’

These questions were addressed, in both species, by a study that used both

mtDNA sequences and a panel of seven microsatellites (Burg & Croxall, 2001).

The results were clearest for mtDNA (Figure 8.3b, c), but those for the micro-

satellites told the same story. For the black-browed species (Figure 8.3b), the

molecular data confirmed the taxonomists’ view that T. impavida was a separate

species, but also demonstrated breeding between this species and T. melanophris

on Campbell Island and indeed the production of hybrids between these two

species there. More surprisingly, these data also demonstrated that the Falkland

Islands support a breeding population of T. melanophris that is quite separate

from an effectively indivisible population shared by Diego Ramirez (Chile), South

Georgia and Kerguelen Island (in spite of the natal philopatry to these three sites).

By contrast, the wider ranging gray-headed albatrosses, from all five of their sites,

seemed to represent a single breeding population (Figure 8.3c) – again in spite of

their natal philopatry.

From a conservation point of view, though, the most important conclusion

relates to T. melanophris. Whereas previously the relative stability of the large

Falkland Islands population was taken as insurance against a real vulnerability of

the species to extinction, now, in the light of these molecular data, the Falkland

Islands population should be considered as somewhat separate from the rest of

the species, which itself is far more threatened with extinction than was previously

appreciated. (A more active and immediate role for molecular markers in practical

matters of conservation is described in Box 8.2.)

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

258

8.2 TOPICAL ECONCERNS

8.2 Topical ECOncerns

As we shall discuss more fully in Chapter 12, there

is an increasingly frequent conflict between exploit-

ing natural populations as a necessary source of

food and conserving those same populations, both

as an end in itself and so that future generations have

something to eat. In Canada, for example, Pacific

salmonid fish are harvested from a large number

of commercial (industrial) and sport fisheries, each

managed in its own way in an attempt to ensure its

continued viability. So, for instance, a fishery may

be closed altogether at times when fish from other

sources are readily available, in order to allow the

stock to breed and recover. Nonetheless, threats to

sustainability are very real: 2002 saw the first designa-

tion of a Canadian salmon stock, the Interior Fraser

River coho salmon, as ‘endangered’, and many others

require careful protection.

In an ideal world, policing, and hence management,

of the different fisheries would be perfectly effective.

But in reality, illegal fishing is bound to take place and

cannot necessarily be countered simply by catching

offenders ‘in the act’. An alternative, then, or at least

another weapon in the managers’ armoury, is to be

able to identify fish as having been illegally obtained

at some other point in the chain from being caught to

being eaten. Molecular markers make this possible.

The forensic analysis of the origins of our food

molecular markers in

conservation

9781405156585_4_008.qxd 11/5/07 14:54 Page 258