Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

FEMINISM

Feminism in Russia first developed during the

1850s, following the disastrous Crimean War and

the accession of Alexander II. At a time of political

ferment over the nation’s future, an intense debate

arose within educated society over the dependent

status of women and inherited assumptions about

their capacities and their roles. The idea of women’s

emancipation was readily linked to peasant eman-

cipation, plans for which were being publicly de-

bated during these years. If one section of the

population—enserfed peasants—could be liberated,

why not women too, half the human race? Many

activists in the women’s movement over the next

half–century pinpointed the 1850s and 1860s as

the moment when women first challenged their

own subordinate legal status, inferior education,

exclusion from all but menial paid employment,

and vulnerability to sexual exploitation, as well as

the complex web of convention and sanction that

restricted their everyday lives. A number of women

writers—and some radical male writers—had al-

ready addressed these themes a generation earlier,

but always as individuals. It was only during the

1850s that a women’s movement, dedicated to

change, could coalesce.

Unlike women in many western countries,

Russian upper– and middle–class women kept their

property upon marriage and were not forced into

financial dependence on their husbands. However,

even propertied women were disadvantaged by in-

ferior inheritance rights; despite their financial au-

tonomy, the law required that they obey their

husbands and live in the marital home unless given

formal permission to leave. In an abusive marriage

a woman could apply to the courts for legal sepa-

ration, but this was a tortuous process and avail-

able only to the relatively well–to–do. The vast

majority of Russian women in this period were

peasants; before 1861 many were serfs. Even after

peasant emancipation their status in the family was

subordinate, particularly as young women. They

were valued in the village for their ability to work—

in the fields and in the household—and to produce

and raise children. Few had time to think about the

possibilities of an alternative life or about their

own lack of rights or status. It was feminists and

female radicals who first set out to improve

women’s personal rights and establish their legal

and actual autonomy, though the prevailing social

conservatism on gender issues and the extreme lim-

itations on political campaigning impeded any

meaningful legislative change until the last years

of tsarist rule.

Feminist ideas in Russia were inspired not only

by social and political change at home, but equally

by the emerging women’s movement in the West

(particularly North America, Britain, and France)

in this period. Russian feminists established lasting

contacts with their western counterparts and read

western literature on the “woman question.” Most

considered themselves “westernizers” rather than

“slavophiles” in the contemporary political–cultural

controversy over Russia and its future. The word

“feminism” itself was rarely used in Russia or else-

where, and even when it gained wider currency to-

ward the end of the century, it most often had a

pejorative connotation, both for conservative and

radical opponents of reformist women’s move-

ments, and for feminists too. Before 1905 they

called themselves “activists in the women’s move-

ment” (deyatelnitsy zhenskogo dvizheniya). During

the 1905 Revolution, when the movement was

politicized, the most uncompromising became

“equal–righters” (ravnopravki), emphasizing the

struggle for social equality overall, not just for

women. After 1917 feminist activists either emi-

grated or were silenced, and for the entire Soviet pe-

riod feminism was branded a “bourgeois deviation.”

RADICAL ALTERNATIVES TO FEMINISM

Like feminists, revolutionary women and men es-

poused sexual equality. But they fiercely rejected

feminism, insisting that women’s liberation must

be part of a wider social revolution. Feminists, they

claimed, based their appeal to women by driving a

wedge between men and women of the oppressed

classes struggling for their rights. Feminists denied

the radical claim that they were motivated only by

their own “selfish” ends, and saw themselves work-

ing for Russia’s “renewal” and “regeneration,” for

the betterment of the whole population.

Although a socialist women’s movement de-

veloped in Russia (as elsewhere) around 1900, both

populist and Marxist revolutionary groups were

antagonistic to separate work among women, and

only well after 1900 was it possible for Bolshevik

women (such as Alexandra Kollontai, Inessa Ar-

mand, and Nadezhdaya Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife)

to address women’s issues specifically within their

party organization. Though dubbed a “Bolshevik

feminist” by later western historians, Kollontai

herself was one of the most outspoken critics of

reformist feminism—and the very concept of femi-

nism—before and after 1917.

FEMINISM

493

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Disagreements between feminist reformers and

radicals were present from the beginning. At first

these conflicts were more over lifestyle than poli-

tics. Reformers observed existing social codes (dress,

comportment, family obligations, respectability).

Many, though not all, came from well-to-do gen-

try backgrounds and had no need to earn a living.

Radicals, often of gentry origin too, were in con-

scious revolt against family and social propriety.

They wore cropped hair and simple, unadorned

clothing, smoked in public, and called themselves

“nihilists” (nigilistki). Whether in financial need or

not (many were), nihilists joined urban “com-

munes,” or set up their own. For a few years there

was some contact (including individual friendships)

between nihilists and feminists, focusing on at-

tempts to set up an employment bureau for women

and cooperative workshops providing employment

and essential skills for themselves and other

women. This collaboration foundered during the

mid-1860s; within a few years many nihilist

women had moved into illegal populist groups

whose aim was the liberation of the “Russian peo-

ple,” the narod. In their own estimation, by the

early 1870s the radicals had left the “woman ques-

tion” behind.

FEMINIST CAMPAIGNING

The reformers were dedicated to working within

the system. They raised petitions, lobbied minis-

ters, and exploited personal connections to reach

influential figures, many of them already sympa-

thetic to feminist ideas. Of necessity, they focused

on philanthropy and higher education. Philan-

thropy was the one form of public activity then

open to women, an acknowledged extension of

their “caring” role within the family. It aimed both

to encourage self-sufficiency in the beneficiaries and

to give their organizers practical experience of pub-

lic administration. Feminist philanthropists ran

their enterprises, as far as was possible, democra-

tically and with minimal regulation. Most suc-

cessful was a Society to Provide Cheap Lodgings

(founded in 1861 and by 1880 a major charity) in

St. Petersburg. Another society provided refuges for

poor women. A major feminist preoccupation, par-

ticularly important in a rapidly urbanizing society,

was to provide poorer women with alternatives to

prostitution.

Campaigns for higher education were a new

departure, but still within a familiar realm—

woman as educator of her children—a role that be-

came increasingly important in Russia’s drive to

“modernize.” Feminists received support from in-

dividual professors and even university adminis-

trations. Persistent lobbying of government led to

permission for public lectures for women (1869),

then preparatory courses and finally university–

level courses (1872 in Moscow), all existing on

public goodwill, organization, and funding. Med-

ical courses (for “learned midwives”) were opened

to women in St Petersburg (1872), extended to full

medical courses in 1876. In 1878 the first Higher

Courses for Women opened in St. Petersburg, fol-

lowed by Moscow, Kiev, and Kazan. Though out-

side the university system, with no rights to state

service and rank as given to men, these courses

were effectively women’s universities. Feminist

campaigners also provided financial resources to

students needing assistance, setting up a charity to

raise money for the Higher Courses in 1878.

The campaign for higher education and spe-

cialist training was critically important for radical

women too. Radicals’ increasing identification with

FEMINISM

494

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet communism declared gender equality, as celebrated in

this 1961 postcard, reading “Glory to Soviet Women!”

© R

YKOFF

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

“the people” inspired them to train for professions

that could be of direct use, principally teaching and

medicine. During the early 1870s dozens of radi-

cal women (along with nonpolitical women in

search of professional education not then available

in Russia) went abroad to study, especially to

Zurich, where the university was willing to admit

them. Some radicals completed their training; oth-

ers were drawn into Russian émigré political cir-

cles, abandoned their studies, and soon returned to

Russia as active revolutionaries.

Feminism—like all reform movements in Rus-

sia during the 1870s—suffered in the increasingly

repressive political environment. All independent

initiatives, legal or illegal, came under suspicion:

these included a feminist publishing cooperative

founded during the mid-1860s, fundraising activ-

ities, proposals to form women’s groups, and so

forth. Alexander II’s assassination in 1881 brought

further misfortune. Several of the terrorist leaders

were women, former nigilistki, and in the whole-

sale assault on liberalism following the murder,

feminists were tarred with the same brush. The re-

action after 1881 proved almost fatal. Expansion

of higher education was halted; some courses were

closed. Feminists ceased campaigning, and all av-

enues for action were barred. Only during the

mid-1890s could feminists begin to regroup, but

under strict supervision, and always limited by law

to education and philanthropy.

POLITICAL ACTION

Before 1900 Russian feminism had no overt polit-

ical agenda. For some activists this was a matter

of choice, for many others a frustrating restriction.

In several, though not all, western countries

women’s suffrage had been a focal point of femi-

nist aspirations since the 1850s and 1860s. When

rural zemstvos and municipal dumas were set up

in Russia in the 1860s, propertied women received

limited proxy rights to vote for the assemblies’ rep-

resentatives, but legal political activity—by either

gender—was not permitted. Indeed, no national

legislature existed before 1906, when the tsar was

forced by revolutionary upheaval to create the State

Duma. It was during the build up of this opposi-

tion movement, from the early 1900s, that Russ-

ian feminism began to address political issues, not

only women’s suffrage, but calls for civil rights

and equality before the law for all citizens.

After Bloody Sunday (January 9, 1905), fem-

inist activists began to organize, linking their cause

with that of the liberal and moderate socialist

Liberation Movement. Besides existing women’s so-

cieties, such as the Russian Women’s Mutual Phil-

anthropic Society (Russkoye zhenskoye vzaimno–

blagotvoritelnoye obshchestvo, established in 1895),

new organizations sprang up. Most directly polit-

ical was the All-Russian Union of Equal Rights

for Women (Vserossysky soyuz ravnopraviya zhen-

shchin), dedicated to a wide program of social and

political reform, including universal suffrage with-

out distinction of gender, religion, or nationality.

It quickly affiliated itself with the Union of Unions

(Soyuz soyuzov). Feminist support for the Liberation

Movement was unmatched by the movement’s

support for women’s political rights, and much of

the union’s propaganda during 1905 was directed

as much at the liberal opposition as at the govern-

ment. Unlike the latter, however, many liberals

were gradually persuaded by the feminist claim,

and support increased significantly in the years of

reaction that followed. The government refused to

consider women’s suffrage at any point.

The women’s union—though itself overwhelm-

ingly middle-class and professional—was greatly

encouraged by women’s participation in workers’

strikes during the mid-1890s and, particularly,

women’s involvement in working-class action in

1904 and 1905. After 1905, however, feminists

were increasingly challenged by revolutionary so-

cialists in a competition to “win” working–class

women to their cause. Prominent Bolsheviks such

as Kollontai had finally convinced their party lead-

ers of working–class women’s revolutionary po-

tential. During the last years of tsarist rule, when

the labor movement overall was becoming in-

creasingly active, Kollontai and her comrades ben-

efited from the feminists’ failure to make any

headway in the mass organization of women, a

failure exacerbated after the outbreak of World War

I by the feminists’ stalwart support for the war ef-

fort. It was the Bolsheviks, not the feminists, who

capitalized on the war’s catastrophic impact on the

lives of working–class women and men.

With the outbreak of the February Revolution

of 1917, the feminist campaign resumed, and ini-

tial opposition from the Provisional Government

was easily overcome. In the electoral law for the

Constituent Assembly, women were fully enfran-

chised. Before it was swept away by the Bolshe-

viks, the Provisional Government initiated several

projects to give women equal opportunities and pay

in public services, and full rights to practice as

lawyers. It also proposed to transform the higher

FEMINISM

495

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

courses into women’s universities; in the event, the

courses were fully incorporated into existing uni-

versities by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

During the 1920s, with “bourgeois feminism”

silenced, women’s liberation was sponsored by the

Bolsheviks, under a special Women’s Department

of the Communist Party (Zhenotdel). In 1930 the

Zhenotdel was abruptly dismantled and the “woman

question” prematurely declared “solved.”

See also: KOLLONTAI, ALEXANDRA MIKHAILOVNA; KRUP-

SKAYA, NADEZHDA KONSTANTINOVNA; MARRIAGE

AND FAMILY LIFE; ZHENOTDEL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkinson, Dorothy; Dallin, Alexander; and Warshofsky,

Lapidus, eds. (1977). Women in Russia. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1979). Bolshevik Feminist: The

Life of Aleksandra Kollontai. Bloomington: Indiana

University Press.

Clements, Barbara Evans; Engel, Barbara Alpern; and

Worobec, Christine, D., eds. (1991). Russia’s Women:

Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Edmondson, Linda. (1984). Feminism in Russia, 1900-

1917. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Edmondson, Linda, ed. (1992). Women and Society in Rus-

sia and the Soviet Union. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Engel, Barbara Alpern. (1983). Mothers and Daughters:

Women of the Intelligentsia in Nineteenth–Century Rus-

sia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Farnsworth, Beatrice, and Viola, Lynne, eds. (1992).

Russian Peasant Women. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Glickman, Rose L. (1984). Russian Factory Women: Work-

place and Society, 1880-1914. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Noonan, Norma Corigliano, and Nechemias, Carol, eds.

(2001). Encyclopedia of Russian Women’s Movements.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Norton, Barbara T., and Gheith, Jehanne, M., eds. (2001).

An Improper Profession: Women, Gender, and Journal-

ism in Late Imperial Russia. Durham, NC: Duke Uni-

versity Press.

Stites, Richard. (1978). The Women’s Liberation Movement

in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860-

1930. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

L

INDA

E

DMONDSON

FERGHANA VALLEY

A triangular basin with rich soil and abundant wa-

ter resources from the Syr Darya River, modern

canals, and the Kayrakkum Reservoir; the Ferghana

Valley (Russian: Ferganskaia dolina; Uzbek: Farg-

ona ravnina) is situated primarily in Uzbekistan and

partly in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and is formed

below the Tien Shan Mountains to the north and

the Gissar Alay Mountains to the south. This has

been the agricultural center of Central Asia for the

last several thousand years. The basin is a major

producer of cotton, fruits, and raw silk. It is one

of the most densely populated regions of Central

Asia, including the cities of Khujand, Kokand, Fer-

ghana, Margilan, Namangan, Andijan, Osh, and

Jalalabad.

Throughout its history, material and cultural

wealth have made the valley a frequent target of

conquest. Khujand, at the western edge of the val-

ley, was once called “Alexandria the Far” as an out-

post of Alexander the Great’s army. From the third

century the valley emerged as a Persian–Sogdian

nexus and major stop along the Silk Road under

the suzerainty of the Sassanids. The Chinese Tang

Dynasty briefly exerted influence in the valley dur-

ing the seventh and eighth centuries, followed by

Arab conquest and Islamic conversions during the

eighth and ninth centuries and Persian Samanid do-

minion during the tenth century. The rise of the

Karakhanids brought lasting Turkicization of

the Ferghana Valley during the eleventh century.

The Chaghatay Ulus of the Mongol Empire dur-

ing the thirteenth century and the Turkic Timur

(Tamerlane) and his grandson Ulugh Bek during

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries introduced a

period of burgeoning literature and Islamic erudi-

tion, followed by centuries of shifting local pow-

ers and instability under the various Turkic groups.

Kokand khans ruled from the late eighteenth cen-

tury until the Russian Empire annexed the valley

as the Ferghana oblast to the Turkestan gover-

nor–generalship in 1876.

During the establishment of Soviet power in

Central Asia (1920s and 1930s), the valley provided

a fertile area for the Basmachi movement. In 1924,

it was divided between the Uzbek SSR, the Tajik

ASSR, and the Kirgiz ASSR. As a result, the valley

inherited several cross border enclaves in a tradi-

tionally interwoven ethnic region. Despite a tradi-

tion of multiethnic cooperation, late–Soviet unrest

and ethnic clashes erupted there in 1989 between

FERGHANA VALLEY

496

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Uzbeks and Meshkhetian Turks, and in 1990 be-

tween Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in Osh. The famous Fer-

ghana Canal was an early Soviet engineering

project celebrated in prose, poetry, and film.

See also: BASMACHIS; CENTRAL ASIA; UZBEKISTAN AND

UZBEKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Manz, Beatrice Forbes. (1987). “Central Asian Uprisings

in the Nineteenth Century: Ferghana Under the Rus-

sians.” Russian Review 46 (3):267–281.

Tabyshalieva, Anara. (1999). The Challenge of Regional Co-

operation in Central Asia: Preventing Ethnic Conflict in

the Ferghana Valley. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute

of Peace.

M

ICHAEL

R

OULAND

FEUDALISM

According to the nearly unanimous consensus of

Western scholars, pre–Soviet Russian scholars, and

most Soviet scholars until the mid– to late–1930s,

feudalism never appeared in Russia. By the end of

the 1930s, however, it became the entrenched

dogma in the Soviet Union that Russia had expe-

rienced a feudal period. Post–Soviet Russian histo-

rians have been unable to rid themselves of this

erroneous interpretation of their own history, in

spite of Western arguments to the contrary that

have been advanced since 1991.

The fundamental issue is whether the term

“feudalism” has any meaning other than “agrarian

regime,” that is, that most of the population lives

in the countryside and makes its living from farm-

ing and that most of the gross domestic product is

derived from agriculture. If that is all it means, then

Russia was feudal until after World War II. Most

definitions of feudalism, however, involve other

criteria as well, which, as defined by George

Vernadsky and others, typically encompass: (1) a

fusion of public and private law; (2) a dismember-

ment of political authority and a parcellization of

sovereignty; (3) an interdependence of political and

economic administration; (4) the predominance of

a natural, i.e., nonmarket, economy; (5) the pres-

ence of serfdom. Presumably all of these criteria,

not just one or two, should be present for there to

be feudalism in a locality.

The first historian to posit the existence of feu-

dalism in Russia was Nikolai Pavlov–Silvansky

(1869-1908), who based his theory primarily on

the political fragmentation of Russia from the col-

lapse of the Kievan Russian state in 1132 to the

consolidation of Russia by Moscow by the early

sixteenth century. The basic problem with that the-

sis is that there was no serfdom until the 1450s.

Moreover, there were no fiefs. In 1912 Lenin de-

fined feudalism as “land ownership and the privi-

leges of lords over serfs.” Mikhail Pokrovsky

(1868-1932) worked out a “Soviet Marxist” un-

derstanding of Russian feudalism and traced its ori-

gin and major cause (large landownership) to the

thirteenth century. “Feudalism” was necessary to

legitimize the October Revolution and Soviet power.

According to Marx, human history went through

the stages of (1) primordial/primitive communism;

(2) slave–owning; (3) feudalism; (4) capitalism; (5)

imperialism; (6) socialism; (7) communism. The

fact that Russia in reality never experienced “stages”

two through five made it difficult to claim that

the October Revolution was historically inevitable

and therefore legitimate. Inventing “stages” three

through five was therefore politically necessary.

A major problem for the Soviets was that Rus-

sia never knew a slave–owning stage (as in Greece

and Rome). This “problem” was worked out in the

early 1930s by a Menshevik historian, M. M.

Tsvibak (who was liquidated a few years later in

the Great Purges), with the claim that Russia had

bypassed the slave–owning period entirely, that

feudalism arose about the same time as the Kievan

Russian state during the ninth century, or even ear-

lier. Boris Grekov, the “dean” of Soviet historians

between 1930 and 1953 (he allegedly had no use

for Stalin), earlier had alleged that Russia had

passed through a slave–owning stage, but he took

the Tsvibak position in the later 1930s, and that

remained the official dogma to the end of the So-

viet regime. As a result, nearly all of Russian and

Ukrainian history was deemed feudal and succeeded

by “capitalism” with the freeing of the serfs from

seignorial control in 1861.

See also: MARXISM; PEASANTRY; SLAVERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vernadsky, George. (1939). “Feudalism in Russia.” Specu-

lum 14:302-323.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

FEUDALISM

497

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

FILARET DROZDOV, METROPOLITAN

(1782–1867), Metropolitan of Moscow, theologian,

and churchman.

Throughout his long career, Filaret (Vasily

Mikhailovich Drozdov) played a central role in im-

portant matters of church, state, and society: as a

moving force behind the Russian translation of the

Bible, as a teacher of the Orthodox faith through

his famous catechism, sermons, and textbooks, and

as a reformer of the church, particularly its monas-

teries. His widespread reputation as a man of pro-

found faith and great integrity made him the

government’s natural choice to compose the eman-

cipation manifesto ending serfdom in 1861. When

he died in 1867, the country went into mourning.

As Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the future over-

procurator of the Holy Synod, wrote on the day of

the metropolitan’s funeral: “The present moment

is very important for the people. The entire people

consider the burial of the metro[politan] a national

affair.”

Filaret’s early career focused on reform of reli-

gious education, which he shifted from the Latin

scholastic curriculum of the eighteenth century to

a Russian and Bible-centered one during the early

nineteenth century. He wrote two Russian text-

books in 1816 inaugurating a new Orthodox Bib-

lical theology: An Outline of Church-Biblical History

(Nachertanie tserkovno-bibleiskoi istorii) and Notes on

the Book of Genesis (Zapiski na knigu Bytiya). By this

time he was also heavily engaged in a contempo-

rary Russian translation of the Bible that would

carry the Christian message to the Russian people

more effectively than the Slavonic Bible published

during the previous century. He personally trans-

lated the Gospel of John. In 1823 he wrote a new

Orthodox catechism with all of its Biblical citations

in Russian. His abilities and work quickly advanced

his career. He became a member of the Holy Synod

in 1819 and archbishop of Moscow in 1821 (met-

ropolitan in 1826).

Filaret’s new Bible and catechetical initiatives

provoked opposition in church and governing cir-

cles, who saw them as signs of Orthodoxy’s deep-

ening dependence on Protestantism. The critics soon

stopped the Bible translation, burned its completed

portions, and redirected church education on what

Filaret called the “reverse course to scholasticism.”

His catechism was reissued in 1827 in revised form

and in Slavonic. Under these circumstances, Filaret

had to rethink his own position and ideas.

While he never departed from his belief that the

church must communicate its teachings in a lan-

guage people could understand (he finally won

publication of a Russian translation of the Bible

during the more liberal reign of Alexander II), Fi-

laret now gave his ideas a more explicitly patristic

underpinning, as evidenced in the dogmatic theol-

ogy he eloquently and poetically expressed in his

sermons. Moreover, he sponsored publication of the

Writings of the Holy Fathers in Russian Translation

(1843–1893). One eminent Russian theologian

identifies the new work as the crucial moment in

the “awakening of Orthodoxy” in modern times,

the moment when Russian theology began to re-

cover the teachings of the Eastern church fathers

and to define itself with respect to both Roman

Catholicism and Protestantism.

While many aspects of Filaret’s activity as a

leader of the Russian church for more than forty

years bear mentioning, his efforts to reform and

strengthen monasticism stand out. He promoted

contemplative asceticism (hesychasm) on the terri-

tory of the Holy Trinity–St. Sergius monastery and

elsewhere. Fully reformed monasteries, he believed,

might inspire the return of the Old Ritualist and

reconvert Byzantine Rite Catholics (Uniates) of

Poland. He encouraged informal women’s com-

munities to become monasteries, and during the

1860s devised badly needed guidelines for all

monasteries, stressing wherever possible that they

follow the rule of St. Basil with its obligation for

a common table, community property, work, and

prayer. Filaret was canonized as a saint in 1992.

See also: METROPOLITAN; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH;

SAINTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Florovsky, Georges. (1979–1985). Ways of Russian The-

ology, vol. 1, chap. 5. Belmont, MA: Nordland.

Nichols, Robert L. (1990). “Filaret of Moscow as an As-

cetic.” In The Legacy of St. Vladimir: Byzantium, Rus-

sia, America, eds. J. Breck, J. Meyendorff, and E. Silk.

Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

R

OBERT

N

ICHOLS

FILARET ROMANOV, PATRIARCH

(c. 1550–1633), Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus

(1619–1633).

Born Fedor Nikitich Romanov, the future Pa-

triarch Filaret came from an old boyar clan, known

FILARET DROZDOV, METROPOLITAN

498

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

variously from the fourteenth century as the

Koshkins, the Zakharins, the Iurevs, and finally as

the Romanovs. The clan reached the height of

power and privilege after 1547, when Tsar Ivan IV

(“the Terrible”) married Anastasia Iureva, Fedor

Nikitich’s aunt (Fedor was probably born after the

wedding). During the reign of Ivan the Terrible’s

son and heir, Tsar Fedor Ivanovich (1584–1598),

Fedor Nikitich Romanov succeeded his father,

Nikita Romanovich Iurev, on a regency council that

ruled along with Tsar Fedor. Fedor Nikitich had

been a boyar since 1587. He was regional gover-

nor (namestnik) of Nizhnii Novgorod (1586) and

later of Pskov (1590) and served in numerous cer-

emonial functions at court.

On the death of Tsar Fedor in 1598, Fedor

Nikitich continued to hold important posts and re-

tained his seniority among the boyars under the

new tsar, Boris Godunov. In 1601, however, as part

of a general attack by Boris on real and potential

rivals to his power, Fedor was forcibly tonsured

(made a monk) and exiled to the remote Antoniev-

Siisky Monastery, near Kholmogory. His wife,

Ksenia Ivanovna Shestova (whom he married

around 1585), was similarly forced to take the

monastic habit in 1601. She took the religious

name Marfa and was sent in exile to the remote

Tolvuisky Hermitage. Other Romanov relatives—

Fedor’s brothers and sisters and their spouses—

similarly fell into disgrace under Boris Godunov,

with only one of Fedor’s brothers (Ivan) surviving

his confinement.

That Fedor should be considered a rival to Boris

was natural enough. He was the last tsar’s first

cousin, whereas Boris was merely a brother-in-

law. There was also the more or less general belief,

known even to foreign travelers in Russia at the

time, that just before his death, Tsar Fedor had be-

queathed the throne to his cousin Fedor, and that

Boris Godunov had been elected to the throne only

after the Romanovs had first refused it. While there

is enough contemporary evidence to suggest that

the Romanovs were genuinely thought of as can-

didates for the throne in 1598, many of the stories

about Tsar Fedor’s nomination of one of the Ro-

manovs as his heir date from only after the Ro-

manov ascension to the throne (in 1613) and

therefore must be regarded with some suspicion.

Whatever the case, Fedor Nikitich, having taken

the monastic name of Filaret, received some relief

from his circumstances in 1605, when Boris Go-

dunov died and was replaced by the First False

Dmitry, who freed him (and his former wife, the

nun Marfa) from his confinement and elevated him

to the rank of Metropolitan of Rostov. After the fall

of the First False Dmitry, Filaret took charge of the

translation of the relics of Tsarevich Dmitry from

Uglich to Moscow’s Archangel Cathedral in the

Kremlin. This was where Dmitry was interred and,

shortly thereafter, where he was glorified as a saint.

With the election of (St.) Germogen as patriarch,

Filaret was sent back to Rostov; but when the Sec-

ond False Dmitry captured the city in 1608, Filaret

soon became one of his supporters in a struggle

with Tsar Vasily Shuisky (r. 1606–1610), estab-

lishing himself in Dmitry’s camp at Tushino, near

Moscow. It was the Second False Dmitry, in fact,

who elevated Filaret to be patriarch after (St.) Ger-

mogen was murdered by the Poles, who had in-

tervened in Russian internal affairs.

Filaret briefly fell into Polish hands when

Dmitry was defeated and put to flight, but he

quickly made his way back to Moscow under the

protection of Tsar Vasily Shuisky. However, mili-

tary defeats brought Shuisky’s regime down in

1610, and Shuisky was forcibly tonsured a monk.

Political power rested then in a council of seven bo-

yars who dispatched Filaret to Poland to invite

Prince Wladislaw, son of Poland’s King Sigismund

III, to be tsar in Muscovy. During these negotia-

tions, Filaret insisted that the young prince convert

to Orthodoxy and to do so by rebaptism, a stipu-

lation to which the Polish king was unwilling to

concede. With the breakdown of these talks, Filaret

was placed under house arrest, where he remained

until after the Treaty of Deulino in 1618, which

finally provided an end to Polish interests in the

Russian throne.

In June 1619, Filaret returned to a Moscow and

to a Russia ruled now by his son, Mikhail, who

had been elected tsar by the Assembly of the Land

(Zemsky Sobor) in February 1613. Within days, Fi-

laret was consecrated patriarch and within days af-

ter that, he was proclaimed “Great Sovereign”—a

title usually reserved for the ruler—signaling Fi-

laret’s unique position at the court. Filaret took the

reins of government in his own hands, directing

church and foreign policy with evidently little in-

put from his son. In church matters, Filaret con-

tinued his previous position with regard to the

non-Orthodox, insisting on the rebaptism of all

converts and, in general, further hardening con-

fessional lines with Muscovy’s non-Orthodox

neighbors and minorities. He also advocated for the

Polish war that started in 1632, which turned

against Muscovy with the failure of the siege of

FILARET ROMANOV, PATRIARCH

499

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Smolensk and the routing of the Russian army. Fi-

laret died on October 1, 1633, amid the unfolding

disasters of that war.

See also: ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND; CATHEDRAL OF THE

ARCHANGEL; DMITRY, FALSE; GODUNOV, BORIS FYO-

DOROVICH; IVAN IV; KREMLIN; METROPOLITAN;

ROMANOV DYNASTY; ROMANOV, MIKHAIL FYODOR-

OVICH; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; SHUISKY,

VASILY IVANOVICH; TIME OF TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunning, Chester S.L. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War:

The Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov

Dynasty. University Park: Pennsylvania State Uni-

versity Press.

Keep, J.L.H. (1960). “The Regime of Filaret, 1619–1633.”

The Slavonic and Easter European Review 38:334–360.

Klyuchevsky, Vasily Osipovich. (1970). The Rise of the

Romanovs tr. Liliana Archibald. London: Macmillan

St. Martin’s.

Platonov, Sergei Fyodorovich (1985). The Time of Trou-

bles, tr. John T. Alexander. Lawrence: University of

Kansas Press.

R

USSELL

E. M

ARTIN

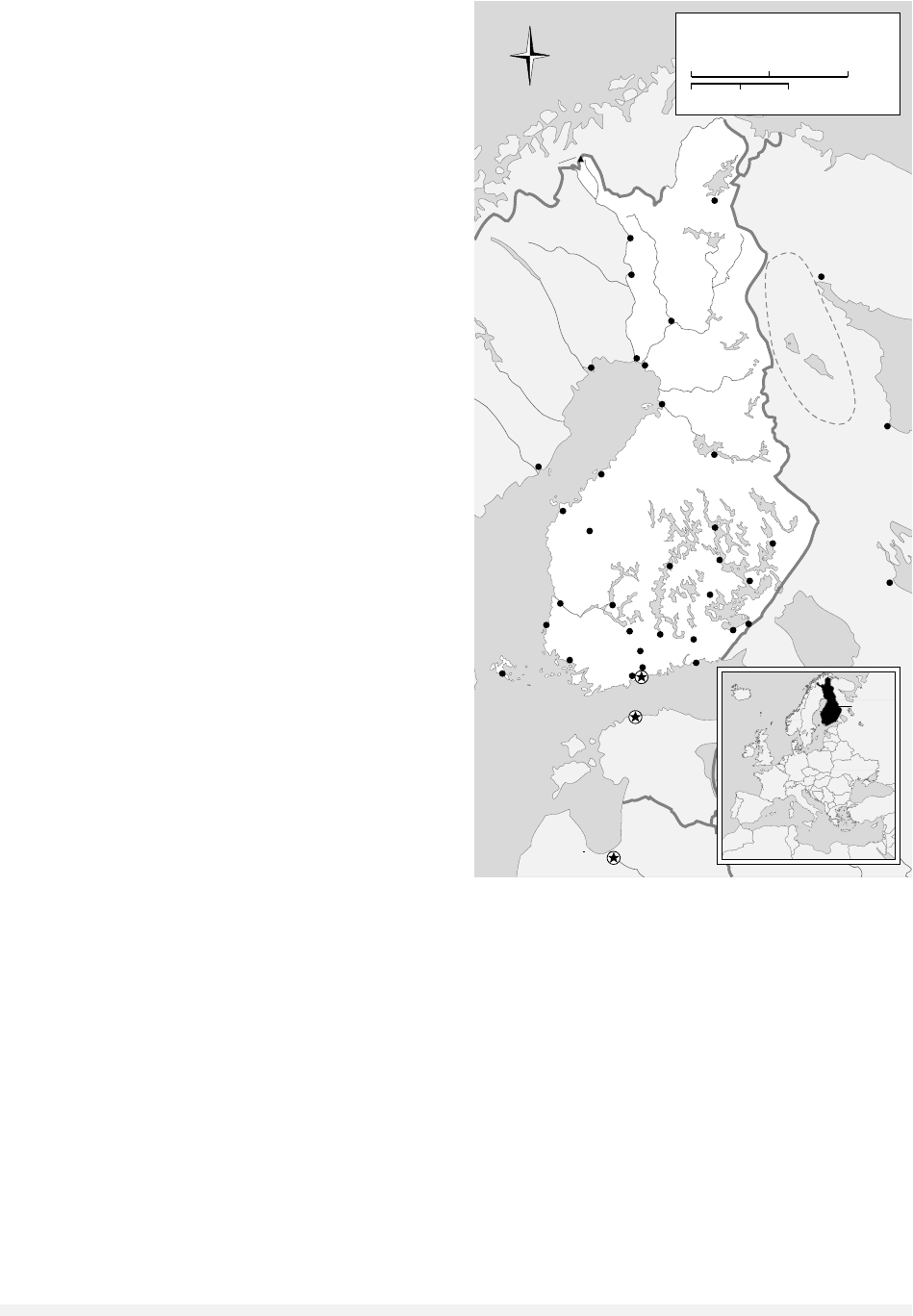

FINLAND

Finland, a country of approximately five million

people, located in northeastern Europe, was part of

the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917. It gained

its independence in the wake of the Bolshevik Rev-

olution in 1917, and had a complex, close, and oc-

casionally troubled relationship with the Soviet

Union. After the collapse of the USSR, Finland be-

gan to turn more toward the West, joining the Eu-

ropean Union in 1995.

Finns are not Slavs. They speak a Finno-Ugric

language, closely related to Estonian and more dis-

tantly to Hungarian. The territory of modern-day

Finland was inhabited as early as 7000 B.C.E., but

there is no written record of the earliest historical

period. During the ninth century C.E., Finns ac-

companied the Varangians on expeditions that led

to the founding of Kievan Rus. The Finnish peoples

maintained close trading ties with several early Russ-

ian cities, especially Novgorod, while from the west

they were influenced by the nascent Swedish state.

UNDER SWEDISH RULE

Starting in the twelfth century, most of Finland

was absorbed by the Swedish kingdom. Legend tells

of a crusade led by King Erik in 1155 that estab-

lished Christianity in Finland. The Swedes and Nov-

gorod fought several conflicts in and around

Finland during this time. The Peace of Noteborg

in 1323 established a rough boundary between

Swedish and Russian lands, with some Finns

(Karelians) living on the eastern side of the border

and adopting the Orthodox faith. Although the

Swedes were Catholic at the time of the conquest,

they broke with Rome under Gustavus Vasa

(1523–1560), and Lutheranism was established as

the official religion of Sweden and Finland in 1593.

The Finnish lands enjoyed some local autonomy

under the Swedes, and the Finnish nobility had cer-

tain political rights. Swedish was the language of

the upper classes and remains an official language

in Finland in the early twenty-first century.

During the mid-sixteenth century, Sweden be-

came embroiled in several wars of religion and state

expansion with Denmark, Poland, and Russia. Rus-

sia and Sweden fought over territory along the Arc-

tic Ocean, and Sweden intervened during Russia’s

Time of Troubles (1598–1613). Later, under Gus-

tavus Adolphus (1611–1632), the Treaty of Stol-

bova (1617) gave substantial territory on both sides

of the Gulf of Finland to Sweden, thereby enabling

it to control trade routes from the Baltic to Russia.

Under Charles XII (1697–1718) and Peter I

(1682–1725), Sweden and Russia fought a major

war for control of the Baltic. In 1714, Russia oc-

cupied Finland after the Battle of Storkro. However,

in 1721, in the Treaty of Nystad (Uusikaupunki),

the Russians withdrew from most of Finland (keep-

ing the region of Karelia in the east) in return for

control over Estonia and Livonia. More than

500,000 Finns, roughly half the population, died

during this long conflict, and the national economy

was ruined. Another war between Russia and Swe-

den from 1741 to1743 again resulted in the Rus-

sian occupation of Finland. However, in accordance

with the Peace of Turku (1743), Russia withdrew

from most of Finland, although it did annex some

additional lands in the eastern part of the country.

There were no further border changes after the

third war between the two states from 1788 to

1790.

UNDER RUSSIAN RULE

In 1808, as a result of a Russian alliance with

Napoleonic France, Russia attacked Sweden and

again occupied Finland. This time, however, Fin-

land was incorporated into the empire as an au-

tonomous grand duchy, with Tsar Alexander I

FINLAND

500

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

becoming its first grand duke. Under this arrange-

ment, the Finns were to enjoy religious freedom,

and Finland, in Alexander’s words, would “take its

place in the rank of nations, governed by its own

laws.” Russia returned land to the Finns, and most

of them accepted Russian rule. During the nine-

teenth century Finland experienced a national

awakening, spurred by developments in the arts,

language, and culture, and political parties began

to organize around national issues. By the end of

the century, when Alexander III and Nicholas II

tried to assert Russia’s authority in Finland, there

was resentment and resistance, culminating in the

assassination of the Russian governor general in

1904.

INDEPENDENCE

Before and during the fateful events of 1917, many

Russian revolutionaries, including Vladimir Lenin,

took refuge in Finland, where there were active so-

cialist and communist parties. After the Bolsheviks

seized power, the Finns, taking advantage of the

breakdown in central authority, declared indepen-

dence on December 6, 1917. Later that month,

Lenin recognized Finnish independence. Nonethe-

less, there was fighting in Finland during the Rus-

sian Civil War between Reds, backed by Moscow,

and anti-communist Whites, backed by Sweden

and Germany. The Whites prevailed, exacting

vengeance on those Reds who did not flee to Rus-

sia. Finland made peace with Russia in 1920 with

the Treaty of Tartu and adopted a constitution cre-

ating a democratic republic that continues to re-

main in effect. During the 1920s and 1930s Finnish

democracy came under assault by both left-wing

and right-wing groups, the former allied with the

communists in the USSR and the latter attracted to

Germany’s Adolf Hitler and Italy’s Benito Mus-

solini.

Finland’s democracy survived, but a more se-

rious threat was posed by Soviet military action.

After the Germans and Soviets carved up Poland

and the Baltic states during the fall of 1939, Fin-

land found itself the target of territorial demands

of Joseph Stalin. The Soviets demanded border

changes around Leningrad and in the far north, is-

lands in the Gulf of Finland, and a naval base in

southern Finland. Diplomatic efforts to find a

peaceful solution failed, and Soviet forces invaded

Finland on November 30, 1939. Finland received

assistance from Western countries, and its forces

fought ferociously against the Soviets, who ac-

cording to some accounts suffered 100,000 dead.

Nonetheless, the Finns were outnumbered and out-

gunned. In March 1940 they agreed to the Soviet

territorial demands, and more than 400,000 Finns

left their homes rather than become citizens of the

Soviet state. Continuing economic and military de-

mands by the USSR eventually made Finland turn

to Germany for assistance. Finnish troops advanced

with the Germans in June 1941 when Germany

attacked the USSR, precipitating, in effect, another

war with the Soviets. In 1943 and 1944, as the tide

of the war turned against Germany, Finland made

FINLAND

501

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mt. Haltia

4,357 ft.

1328 m.

KARELIA

M

u

o

n

i

o

Paijänne

O

u

n

a

s

L

u

r

o

j

o

k

i

T

e

n

o

Inari

K

e

m

i

j

o

k

i

O

u

l

u

j

o

k

i

Oulujärvi

Näsijärvi

Pielinen

White

Sea

Sainaa

Lake

Ladoga

Gulf

of

Riga

T

o

r

n

i

o

j

o

k

i

Baltic

Sea

G

u

l

f

o

f

B

o

t

h

n

i

a

G

u

l

f

o

f

F

i

n

l

a

n

d

Åland

Is.

Kotka

Kouvola

Imatra

Hyvinkää

Hameenlinna

Pori

Lahti

Mikkeli

Varkaus

Joensuu

Petrozavodsk

Kandalaksha

Belomorsk

Kuopio

Kajaani

Jyväskylä

Vaasa

Tornio

Umeå

Luleå

Rovaniemi

Ivalo

Kolari

Muonio

Lappeenranta

Maarianhamina

Kemi

Kokkola

Savonlinna

Rauma

Seinäjoki

Turku

Tampere

Oulu

Vantaa

Espoo

Helsinki

Riga

Tallinn

ESTONIA

SWEDEN

NORWAY

RUSSIA

LATVIA

Finland

W

S

N

E

FINLAND

200 Miles

0

0

200 Kilometers

100

100

Finland, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMIS

-

SION

peace with the USSR and turned on the Germans,

but it had to make additional territorial concessions

to Moscow, most of which were incorporated into

the USSR’s Autonomous Republic of Karelia. Thus

Finland enjoyed the dubious distinction of fighting

both the Soviets and the Germans, and the coun-

try was devastated by years of war.

Although Finland was subjected to Russian in-

fluence during the war, the Finns avoided the fate

of the East European states, which became com-

munist satellites of the Soviet Union. Instead, in

1948, Finland signed an Agreement of Friendship,

Cooperation and Mutual Assistance with the USSR

that allowed it to keep its democratic constitution

but prohibited it from joining in any anti-Soviet

alliance. This agreement is sometimes derided as

“Finlandization”: Finland retained its constitutional

freedoms but gave the USSR an effective veto over

its foreign policy (e.g., it had close trade links with

the USSR but did not join NATO or the European

Community) and, on some questions, its domestic

politics (e.g., anti-Soviet writers could not be pub-

lished in Finland; Finnish politicians had to pub-

licly affirm their confidence in Soviet policy). This

was especially the case under President Urho

Kekkonen (1956–1981), who had close ties with

Moscow. Nonetheless, Finland was generally re-

garded as a nonaligned, neutral state. This culmi-

nated with the Conference on Security and

Cooperation in Europe of 1975, which led, among

other things, to the Helsinki Accords, an important

human rights agreement that would later be used

against the communist rulers of the Soviet Union

and Eastern Europe. During the postwar period,

FINLAND

502

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov signs the Soviet-Finnish Non-Aggression Pact of 1939. Standing behind him are Andrei

Zhdanov, Klimenty Voroshilov, Josef Stalin, and Otto Kuusinen. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS