Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6.13 Additional Problems 259

(a)

OH

(e)

NH

2

(c)

O

Cl

N

H

(b)

OH

N

(d)

O

Cl

OH

OH

OH

Cl

Cl

(a)

2

NH

2

F

(d)

NH

2

(b)

NH

4

(e)

N

+

I

–

(f)

3

(c)

N

NH

2

NH

2

(a) (b)

(c)

N

Ph

CH

3

NH

2

(d)

NH

2

CH

2

NH

2

CH

2

CH

3

OH

CH

3

N

H

3

C

H

3

C

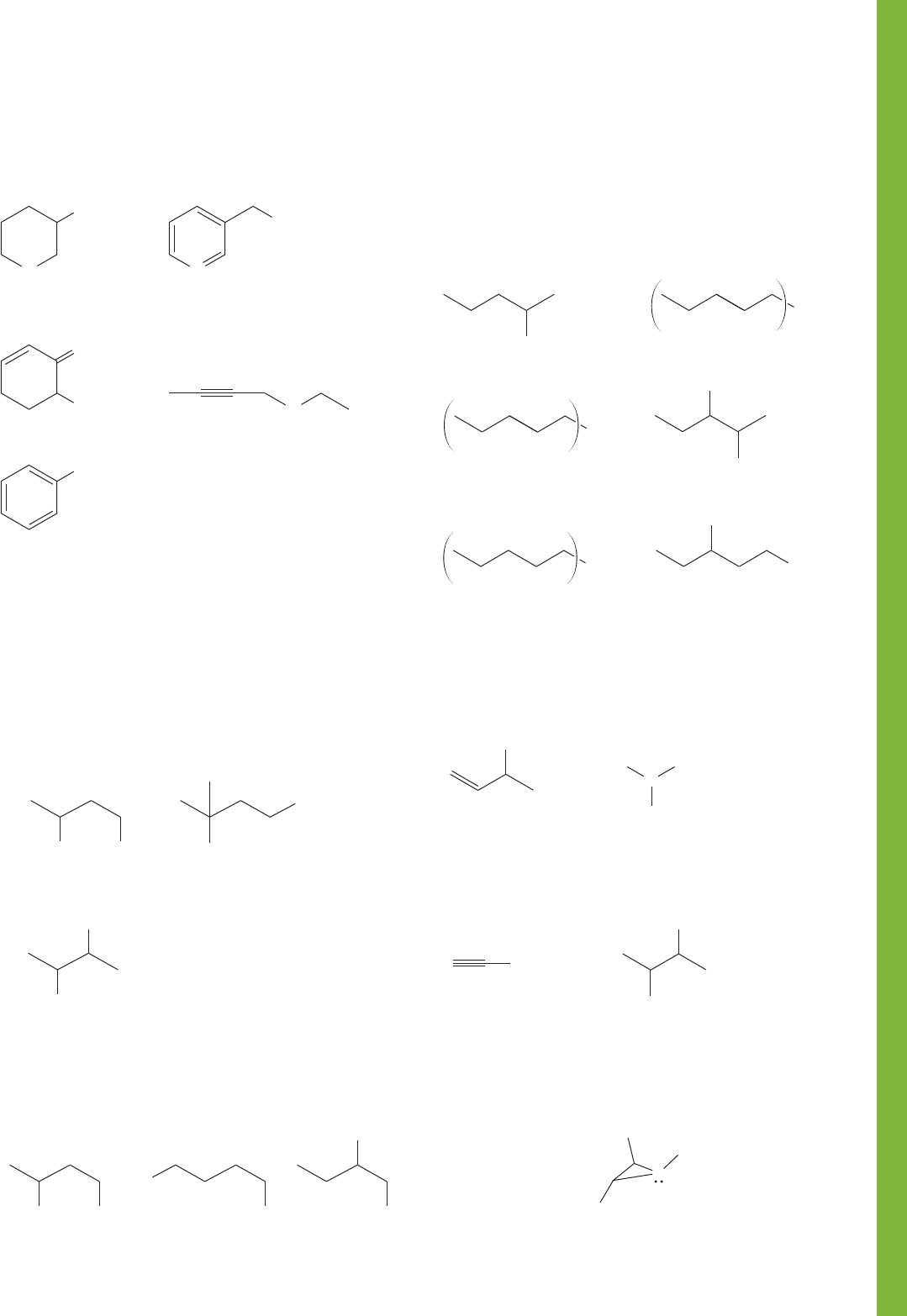

PROBLEM 6.26 Indicate the hybridization of the carbons,

nitrogens, and oxygens in each of the following compounds:

PROBLEM 6.27 Which of the molecules in Problem 6.26 are

able to hydrogen bond with water? Which are able to hydrogen

bond with another molecule of the same structure (i.e., with

themselves)?

PROBLEM 6.28 In the following molecules, there exists the

possibility of forming more than one alkoxide or thiolate. In

each case, explain which will be formed preferentially, and why.

(a)

(solution) (gas phase)

(

solution

)

(b)

(c)

OH

OH

OH

OH

SH

OH

PROBLEM 6.29 Predict the relative acidities of the following

three alcohols:

PROBLEM 6.30 Write all the isomers of the alcohols of the

formula C

6

H

14

O.

PROBLEM 6.31 Name the following compounds (in more than

one way, if possible). Identify each as a primary, secondary, or

tertiary amine, or as a quaternary ammonium ion.

PROBLEM 6.32 Name the following compounds (in more

than one way, if possible). Identify each as a primary, secondary,

or tertiary amine.

PROBLEM 6.33 Explain why the compound below shows five

signals in the

13

C NMR spectrum at low temperature but only

three at higher temperature.

260 CHAPTER 6 Alkyl Halides, Alcohols, Amines, Ethers, and Their Sulfur-Containing Relatives

PROBLEM 6.34 Write the expressions for K

a

and K

b

and show

that pK

a

pK

b

14.

PROBLEM 6.35 The pK

b

values for a series of simple amines

are given below. Explain the relationship between pK

b

and base

strength, and then rationalize the nonlinear order.

Amine NH

3

NH

2

CH

3

NH(CH

3

)

2

N(CH

3

)

3

pK

b

4.76 3.37 3.22 4.20

Use Organic Reaction Animations (ORA) to answer the

following questions:

PROBLEM 6.36 Select the animation of the reaction titled

“Hofmann elimination.” Observe the reagents that are involved.

What type of amine is required for the reaction? Is it primary,

secondary, or tertiary?

PROBLEM 6.37 How would a polar solvent impact the

Hofmann elimination reaction? Would it slow the reaction

::::

down or make the reaction faster? Why? Use an energy diagram

to help explain your answer.

PROBLEM 6.38 There are three products formed in the

Hofmann elimination reaction. They can be seen moving off

the screen at the end at the reaction. Stop the animation while

all three are still on the screen. You should be able to see water,

an alkene, and an amine. Which do you suppose is the best

nucleophile? Select the HOMO representation for the

animation. Remember that the HOMO represents the most

available electrons, in other words, the most nucleophilic

electrons. Based on the calculated HOMO, which of the three

products is the most nucleophilic?

PROBLEM 6.39 Select the animation titled “Carbocation

rearrangement: E1.”There are several intermediates in this

reaction. Which one is the most stable? Which one is the least

stable? What process is occurring in the first step of the

reaction? Use Table 6.4 to explain why the first step occurs.

Substitution and Elimination

Reactions: The S

N

2, S

N

1, E1,

and E2 Reactions

261

7.1 Preview

7.2 Review of Lewis Acids and

Bases

7.3 Reactions of Alkyl Halides:

The Substitution Reaction

7.4 Substitution, Nucleophilic,

Bimolecular: The S

N

2

Reaction

7.5 The S

N

2 Reaction in

Biochemistry

7.6 Substitution, Nucleophilic,

Unimolecular: The S

N

1

Reaction

7.7 Summary and Overview of the

S

N

2 and S

N

1 Reactions

7.8 The Unimolecular Elimination

Reaction: E1

7.9 The Bimolecular Elimination

Reaction: E2

7.10 What Can We Do with These

Reactions? How to Do

Organic Synthesis

7.11 Summary

7.12 Additional Problems

INVERSION In this chapter we will learn that some carbons are like umbrellas.

Both can undergo inversion.

7

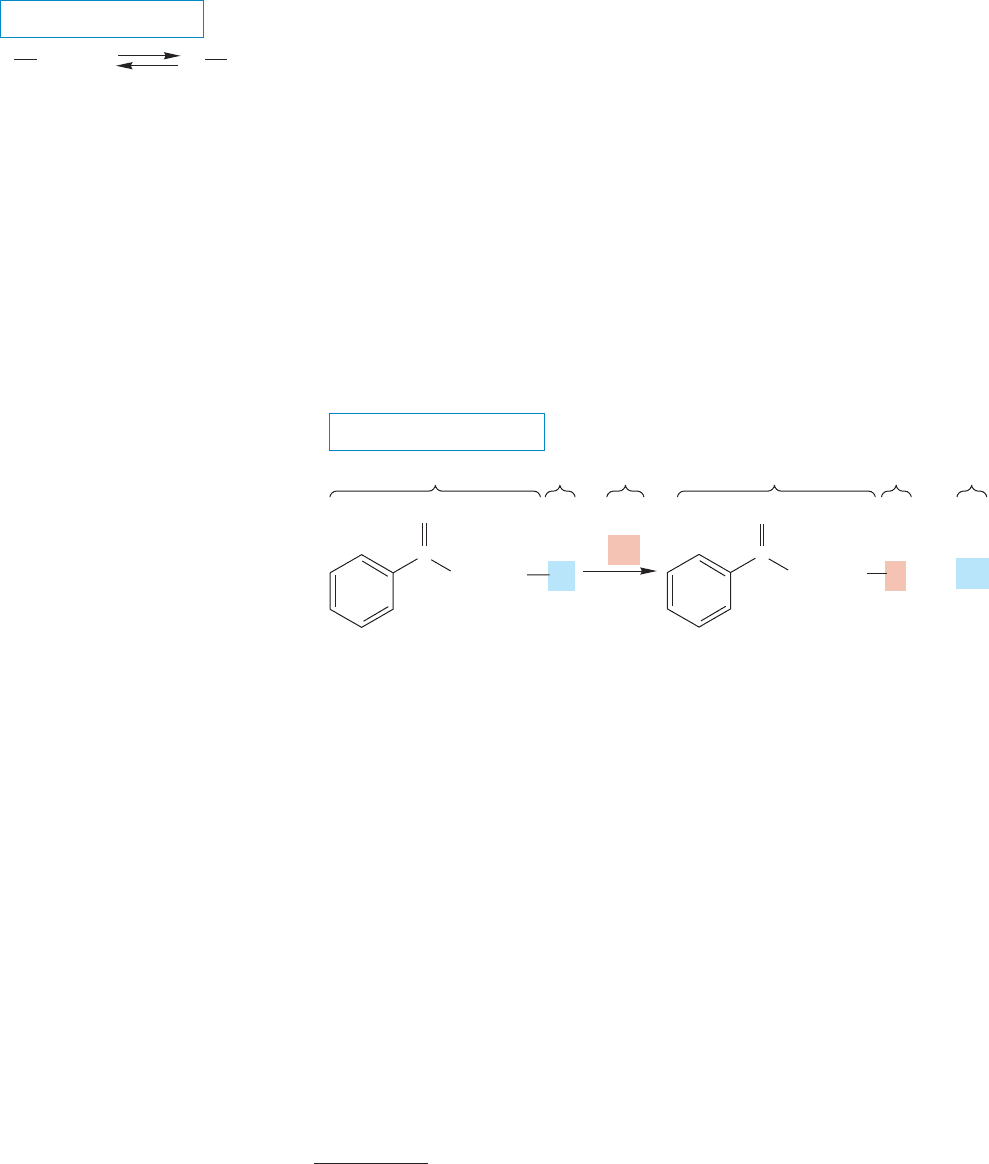

THE GENERAL CASE

H

3

C

Methyl group Isopropyl group

tert-Butyl group

+

L

=

RL

R

R

(CH

3

)

2

CH

(CH

3

)

3

C

+

Ethyl group

CH

3

CH

2

Nu Nu

FIGURE 7.1 This generic reaction

presents an overall picture of the

substitution process. A leaving group,

L, is replaced by a new group, Nu, to

give . A standard set of alkyl

groups that will be used throughout

this chapter is presented.

R

O

Nu

A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

–

..

..

..

..

RLN RNL

Cl

..

..

..

..

–

Na

Na

100

⬚C

24 h

(80%)

+

+

O

..

..

I

..

..

..

+

OCH

2

CH

2

..

..

I

Cl

OCH

2

CH

2

..

..

..

..

..

O

..

..

C

C

FIGURE 7.2 The replacement of one

halogen by another is an example of a

substitution reaction.

1

Satchel Paige (1906–1982) was a pitcher for the Cleveland Indians and later the St. Louis Browns. He was

brought to the major leagues by Bill Veeck after a long and spectacular career in the Negro Leagues.Some meas-

ure of his skill can be gained from realizing that Paige pitched in the major leagues after his 50th birthday.

Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you.

—LEROY ROBERT “SATCHEL” PAIGE

1

7.1 Preview

We are about to embark on an extensive study of chemical change.The last six chap-

ters mostly covered various aspects of structure, and still more analysis of structure

will appear as we go along. Without this structural underpinning no serious explo-

ration of chemical reactions is possible. The key to all studies of reactivity is an ini-

tial, careful analysis of the structures of the molecules involved. We have been

learning parts of the grammar of organic chemistry. Now we are about to use that

grammar to write some sentences and paragraphs. Let’s begin with a reaction cen-

tral to most of organic and biological chemistry, the replacement of one group by

another (Fig. 7.1).

When one group is replaced by another in a chemical reaction, the result is a

subsititution reaction. Conversion of one alkyl halide into another is one example

of the substitution reaction (Fig. 7.2). This reaction looks simple, and in some ways

it is. The only change is the replacement of one halogen by another.

Yet as we examine the details of this process, we find ourselves looking deeply into

chemical reactivity. This reaction is an excellent prototype that nicely illustrates

general techniques used to determine reaction mechanism.

One reason that we spend so much time on the substitution reaction is that it

is so general; what we learn about it and from it is widely applicable. Not only will

we apply what we learn here to many other chemical reactions, substitution reac-

tions have vast practical consequences as well. Substitution reactions, commonly

called displacement reactions, are at the heart of many industrial processes and are

central to the mechanisms of many biological reactions including some forms of

carcinogenesis, the cancer-causing activity of many molecules. Biomolecules are

bristling with substituting agents. It seems clear that when some groups on our DNA

(deoxyribonucleic acid,see Chapter 23) are modified in a substitution reaction, tumor

production is initiated or facilitated. Beware of substituting agents.

This chapter is long, important, and possibly challenging. In it, we cover four of

five building block reactions, two of them substitution reactions (S

N

1 and S

N

2) and

two of them elimination reactions (E1 and E2). We have encountered another fun-

damental reaction, additions, already in Chapter 3, and it will reappear shortly, in

Chapter 9. From now on, you really cannot memorize your way through the material;

262 CHAPTER 7 Substitution and Elimination Reactions

7.2 Review of Lewis Acids and Bases 263

you must try to generalize. Understanding concepts and applying them in new situa-

tions is the route to success. This chapter contains lots of problems, and it is impor-

tant to try to work through them as you go along.We know this warning is repetitious,

and we don’t want to insult your intelligence, but it would be even worse not to alert

you to the change in the course that takes place now or not to suggest ways of getting

through this new material successfully. You cannot simply read this material and hope

to get it all. You must work with the text and the various people in your course, the

professor and the teaching assistants, in an interactive way. The problems try to help

you do this. When you hit a snag or can’t do a problem, find someone who can and

get the answer.The answer is more than a series of equations or structures and arrows;

it also involves finding the right approach to the problem. There is much technique

to problem solving in organic chemistry; it can be learned,and it gets much easier with

practice. Remember: Organic chemistry must be read with a pencil in your hand.

ESSENTIAL SKILLS AND DETAILS

1. We have seen it before, as early as Chapter 1, but in this chapter the curved arrow

formalism becomes more important than ever. If you are at all uncertain of your ability to

“push”electrons with arrows,now is definitely the time to solidify this skill. In the arrow

formalism convention, arrows flow from electrons. But be careful about violating the rules

of valence; arrows either displace another pair of electrons or fill a “hole”—an empty orbital.

2. It is really important to be able to generalize the definition of Lewis bases and Lewis

acids. All electron-pair donors are Lewis bases, and nearly any pair of electrons can act

as a Lewis base under some conditions. Similarly, there are many very different

appearing Lewis acids—acceptors of electrons.

3. The four fundamental reactions we study in this chapter, S

N

2, S

N

1, E2, and E1, are

affected by the reaction conditions as well, of course, as by the structures of the

molecules themselves.These four reactions often compete with each other, and it is

important to be able to select conditions and structures that favor one reaction over the

others. You will rarely be able to find conditions that give specificity, but you will

usually be able to choose conditions that give selectivity.

4. At the end of this chapter, we will sum up what we know about making molecules—

synthesis. ALWAYS attack problems in synthesis by doing them backward. Do not

attempt to see forward from starting material to product. In a multistep synthesis, this

approach is often fatal. The way to do it is to look at the ultimate product and ask

yourself what molecule might lead to it in a single step.That technique will usually

produce one or more candidates.Then apply the same question to those candidates,

and before you know it, you will be at the indicated starting material. This technique

works, and can make what is often a tough, vexing task easy.

5. Alcohols are important starting materials for synthesis—they are inexpensive and easily

available. Alcohols can be made even more useful by learning how to manipulate the

OH group to make it more reactive—to make it a better “leaving group.”Several ways

to do that are outlined in Section 7.4f.

6. Keeping track of your growing catalog of useful synthetic reactions is not easy—it is

a subject that grows rapidly. A set of file cards on which you collect ways of making various

types of molecules is valuable. See page 320 for an outline of how to make this catalog.

7.2 Review of Lewis Acids and Bases

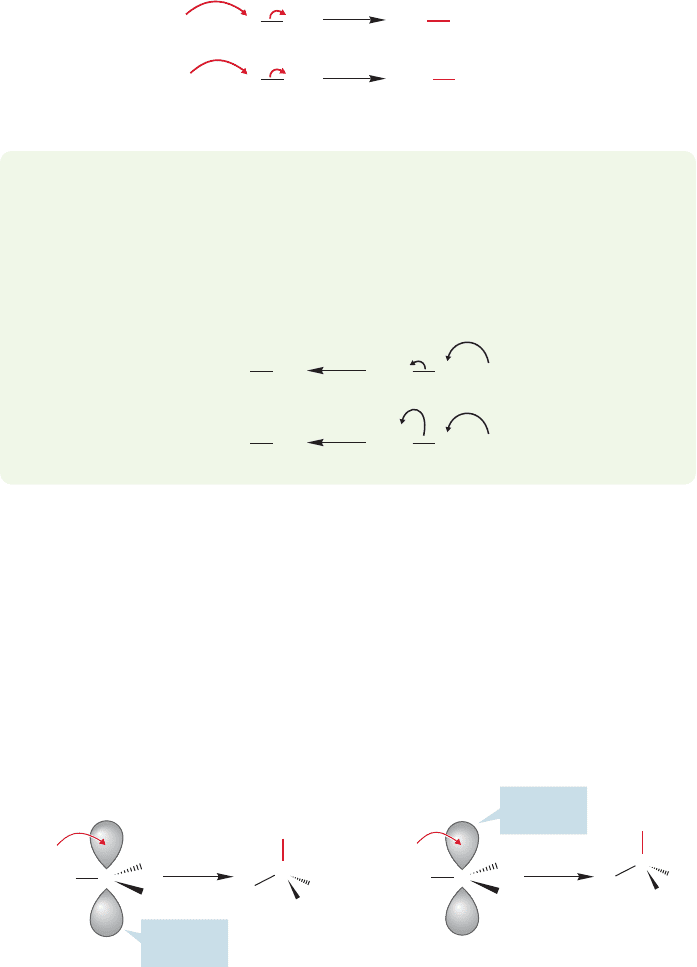

7.2a The Curved Arrow Formalism Recall that there is a most important

bookkeeping technique called the curved arrow formalism (p. 23), which helps to

sketch the broad outlines of what happens during a chemical reaction.However,it does

not constitute a full reaction mechanism, a description of how the reaction occurs.

264 CHAPTER 7 Substitution and Elimination Reactions

–

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

HO H

..

..

–

Cl

..

..

..

HO H

..

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

H

3

NH

–

Cl

..

..

..

H

3

N

+

H

+

+

FIGURE 7.3 Two demonstrations of

the application of the curved arrow

formalism. We will see many other

examples.

+

Empty 2p

orbital

Empty 2p

orbital

F

..

..

..

F

..

F

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

F

F

–

BF

F

F

H

..

–

CH

H

H

B

–

C

H

H

H

H

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

FIGURE 7.4 The fluoride and hydride

ion are Lewis bases reacting with the

Lewis acids BF

3

and

CH

3

.

If a reaction mechanism is not an arrow formalism, what is it? A short answer

would be a description, in terms of structure and energy, of the intermediates and

transition states separating starting material and product. Implied in this descrip-

tion is a picture of how the participants in the reaction must approach each other.

The arrow formalism is a powerful device of enormous utility in helping to keep

track of bond makings and breakings. In this formalism, chemical bonds are shown

as being formed from pairs of electrons flowing from a donor toward an acceptor,

often, but not always, displacing other electron pairs. Figure 7.3 shows two exam-

ples. In the first, hydroxide ion, acting as a Brønsted base, displaces the pair of elec-

trons in the hydrogen–chlorine bond. The reaction of ammonia ( ) with

hydrogen chloride is another example in which the electrons on neutral nitrogen are

shown displacing the electrons in the hydrogen–chlorine bond.

:

NH

3

WORKED PROBLEM 7.1 Draw arrow formalisms for the reversals of the two reactions

in Figure 7.3.

ANSWER This problem may seem to be mindless, but it really is not. The key

point here is to begin to see all reactions as proceeding in two directions. Nature

doesn’t worry about “forward” or “backward.” Thermodynamics dictates the

direction in which a reaction will run.

Cl

..

..

..

HH

–

–

HO

..

..

..

HO

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

HH

–

H

3

N

..

H

3

N

Cl

..

..

..

..

+

+

+

+

+

7.2b Lewis Acids and Bases In Sections 1.7 and 2.15, we began a discus-

sion of acids and bases that will last throughout this book. Then we spent some

time in Chapter 3 reviewing Brønsted acids and bases in the context of the addi-

tion reaction and extended the subject of acidity and basicity to Lewis acids and

Lewis bases. These concepts will hold together much of the material in the

remaining chapters.

Consider two conceptually related processes: the reaction of boron trifluoride

with fluoride ion, F

, and the reaction of the methyl cation with hydride,

(Fig. 7.4).

H

:

-

7.2 Review of Lewis Acids and Bases 265

In these two reactions there is no donating or accepting of a proton, and so

by a strict definition of Brønsted acids and bases we are not dealing with acid–base

chemistry. As we already know, however, there is a more general definition of acids

and bases that deals with this situation. A little review may be helpful: A Lewis

base is defined as any species with a reactive pair of electrons (an electron donor).

This definition may seem very general and indeed it is.It gathers under the “base”

category all manner of odd compounds that don’t really look like bases. The key

word that confers all this generality is reactive. Reactive under what circumstances?

Almost everything is reactive under some set of conditions. And that’s true;

compounds that are extraordinarily weak Brønsted bases can still behave as

Lewis bases.

If the definition of a Lewis base seems general and perhaps vague, the defini-

tion of a Lewis acid is even worse. A Lewis acid is anything that will react with a

Lewis base (thus, an electron acceptor).Therein lies the power of these definitions.

They allow us to generalize—to see as similar reactions that on the surface appear

very different.

To describe Lewis acid–Lewis base reactions in orbital terms, we need only point

out that a stabilizing interaction of orbitals involves the overlap of a filled orbital

(Lewis base) with an empty orbital (Lewis acid) (Fig. 7.5).

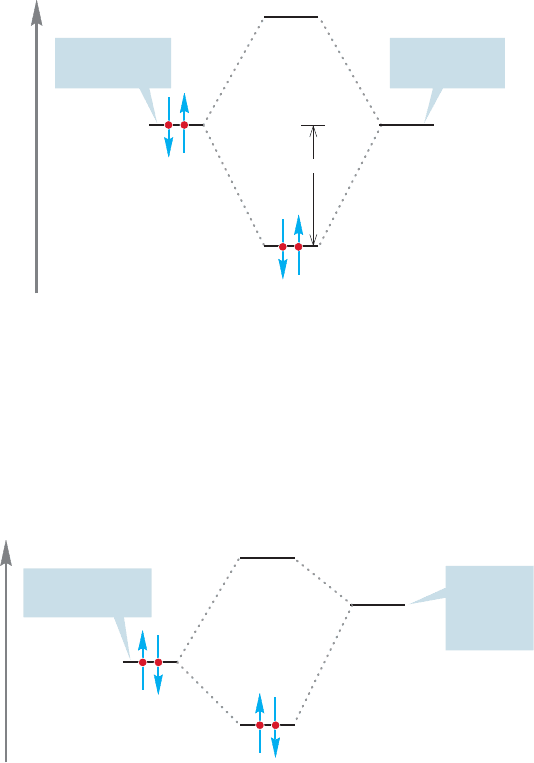

Energy

Empty orbital

(Lewis acid)

Filled orbital

(Lewis base)

Stabilization

FIGURE 7.5 The interaction of a

filled orbital with an empty orbital

is stabilizing.

In the examples in Figure 7.4, the Lewis bases are the fluoride and hydride

ions. In fluoride, the electrons occupy a 2p orbital and in hydride, a 1s orbital.

The Lewis acids are boron trifluoride and the methyl cation, each of which

bears an empty 2p orbital. A schematic picture of these interactions is shown in

Figure 7.6.

Empty 2p

orbital on

carbon or

boron

Filled H (1s)

or F (2p) orbital

Energy

FIGURE 7.6 A schematic interaction

diagram for the reactions of

Figure 7.4.

266 CHAPTER 7 Substitution and Elimination Reactions

AB

LUMO

HOMO

Energy

FIGURE 7.7 In two typical molecules,

the strongest stabilizing interaction is

likely to be between the HOMO of

one molecule (A) and the LUMO of

the other molecule (B), because the

strongest interactions are between the

orbitals closest in energy.

HOMO

F

LUMO

σ∗

B

Energy

F

σ

B

F (2p)

B (2p)

FIGURE 7.8 The interaction of the

LUMO for BF

3

(an empty 2p orbital

on boron) and the HOMO of F

(a filled 2p orbital on fluorine)

produces two new molecular orbitals:

an occupied bonding σ orbital and an

unoccupied antibonding σ* orbital.

7.2c HOMO–LUMO Interactions It is possible to elaborate a bit on the gen-

eralization that “Lewis acids react with Lewis bases” by realizing that the strongest

interactions between orbitals are between the orbitals closest in energy. For stabiliz-

ing filled–empty overlaps, this will almost always mean that we must look at the

interaction of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of one molecule (A)

with the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the other (B) (Fig. 7.7).

PROBLEM 7.2 Identify the HOMO and LUMO in the reaction of the methyl

cation with hydride in Figure 7.4.

WORKED PROBLEM 7.3 Point out the HOMO and LUMO in the following

reactions:

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

HO

.

.

.

.

:

-

+ H

3

O

+

:

U

2 H

2

O

.

.

:

H

3

N

:

+ H

O

Cl

.

.

.

.

:

U

+

NH

4

+

:

Cl

.

.

.

.

:

-

:

-

CH

3

+ H

O

Cl

.

.

.

.

:

U

CH

4

+

:

Cl

.

.

.

.

:

-

H

2

C

P

CH

2

+ BH

3

U

+

CH

2

O

CH

2

O

-

BH

3

HO

.

.

.

.

:

-

+ Li

+

U

HO

.

.

.

.

Li

In the reaction of BF

3

with fluoride, it is the filled fluorine 2p orbital that is the

HOMO and the empty 2p orbital on boron that is the LUMO (Fig. 7.8). All Lewis

acid–Lewis base reactions can be described in similar terms.

(continued)

7.3 Reactions of Alkyl Halides: The Substitution Reaction 267

7.3 Reactions of Alkyl Halides: The Substitution

Reaction

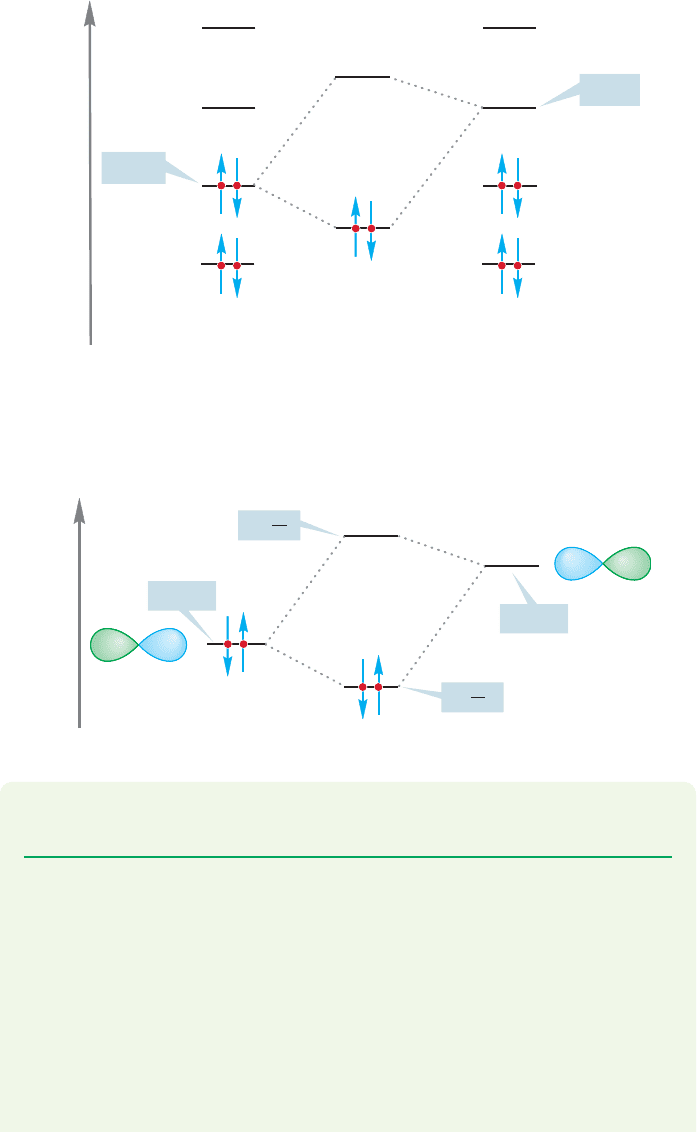

A great many varieties of substitution reactions are known, but all involve a com-

petition between a pair of Lewis bases for a Lewis acid. Figure 7.9 shows five exam-

ples with the substituting group, the nucleophile (from the Greek,“nucleus loving”),

and displaced group, the leaving group,identified. Both the nucleophile (usually Nu)

and leaving group (usually L) are Lewis bases.

ANSWER

(a) HOMO: Filled nonbonding orbital on HO

LUMO: Empty 2s orbital on Li

(b) HOMO: Filled π orbital of ethylene

LUMO: Empty 2p orbital on BH

3

(c) HOMO: Filled sp

3

nonbonding orbital of methyl anion

LUMO: Empty σ

*

orbital of

(d) HOMO: Filled sp

3

nonbonding orbital of ammonia,

LUMO: Empty σ

*

orbital of

(e) HOMO: Filled nonbonding orbital of hydroxide

LUMO: Empty σ

*

orbital of an bond of H

3

O

O

O

H

H

O

Cl

:

NH

3

H

O

Cl

PROBLEM 7.4 Identify the HOMOs and LUMOs in the reactions of Figure 7.9.

K

+

Na

+

(a)

Nucleophile (Nu )

I

..

..

HO

..

..

..

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

H

3

C

N

2

N

2

H

3

CK

+

CH

3

–

..

HO

..

..

..

..

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

I

..

..

..

H

3

C

H

3

C

CH Cl

–

–

(b)

I

..

..

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

Na

+

..

H

3

C N(CH

3

)

3

N(CH

3

)

3

CH

3

–

..

..

..

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

–

Cl

..

..

..

..

CH

3

CH

3

CH

Leaving group ( L)

CH

3

SH

3

CS

+

K

+

Li

+

Li

+

K

+

+

+

+

+

++

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

(c)

–

..

..

NC

(d)

H

3

N

CH

3

H

3

N

+

(e)

–

–

..

NC

..

–

–

I

..

..

..

..

–

I

..

..

..

..

I

..

..

..

..

WEB 3D

FIGURE 7.9 Five examples of the substitution reaction. The nucleophiles for the reactions

reading left to right are (a) hydroxide (HO

), (b) methyl mercaptide (CH

3

S

), (c) cyanide

(NC

), (d) fluoride (F

), and (e) ammonia ( NH

3

).The leaving groups are iodide (I

),

trimethylamine [N(CH

3

)

3

], chloride (Cl

), nitrogen (N

2

), and iodide (I

) again.

:

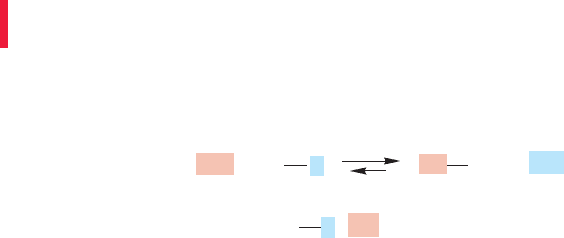

Bimolecular nucleophilic substitution: S

N

2

268 CHAPTER 7 Substitution and Elimination Reactions

–

..

+

+

R

L

LR

Nu

..

Nu

–

..

–

Rate (ν) = k [R L] [ ] Nu

FIGURE 7.10 A bimolecular reaction.

Notice that the reactions in Figure 7.9 are all equilibrium reactions.We will con-

sider equilibrium in detail in Chapter 8, but we need to see here that these compe-

tition reactions are all, in principle at least, reversible. A given reaction may not be

reversible in a practical sense, but that simply means that one of the competitors has

been overwhelmingly successful. There are many possible reasons why this might

be so. One of the equilibrating molecules might be much more stable than the other.

If one of the nucleophiles were much more powerful than the other, the reaction

would be extremely exothermic in one direction or the other.Reactions a–c in Figure 7.9

are examples of this.We are used to thinking of reactions running from left to right,

but this prejudice is arbitrary and even misleading. Reactions run both ways. There

are other reasons one of these reactions might be irreversible. Perhaps the equilib-

rium is disturbed by one of the products being a solid that crystallizes out of the

solution, or a gas that bubbles away. If so, the reaction can be driven all the way to

one side, even against an unfavorable equilibrium constant. Under such circum-

stances, an endothermic reaction can go to completion. In reaction d of Figure 7.9

both propyl fluoride (bp 2.5 °C) and nitrogen are gases, and their removal from the

solution will drive the equilibrium to the right.

The second point to notice is that there is no obligatory charge type in these

reactions. The displacing nucleophile is not always negatively charged (reaction e),

and the group displaced—the leaving group—does not always appear as an anion

(reactions b and d).

If we examine a large number of substitution reactions, two categories emerge.

The boundaries between them are not absolutely fixed, as we will see, but there are

two fairly clear-cut limiting classes of reaction. One is a kinetically second-order

process, common for primary and secondary substrates ( , Section 7.4). The

other is a kinetically first-order reaction,common for tertiary substrates (Section 7.6).

We take up these two reactions in turn, examining each in detail.

7.4 Substitution, Nucleophilic, Bimolecular:

The S

N

2 Reaction

7.4a Rate Law The rate law tells us the number and kinds of molecules involved

in the transition state—it tells you how the reaction rate depends on the concentra-

tions of reactants and products. For many substitution reactions, the rate ν is propor-

tional to the concentrations of both the nucleophile, , and the substrate,

This bimolecular reaction is first order in and first order in substrate,

. The rate constant, k, is a fundamental constant of the reaction (Fig. 7.10).

Here, R stands for a generic alkyl group. Don’t confuse this R with the (R) used to

specify one enantiomer of a chiral molecule. This bimolecular reaction is second

order overall, which leads to the name Substitution, Nucleophilic, bimolecular, or

S

N

2 reaction.

R

O

L

Nu

:

-

[R

O

L].

[Nu

:

-

]

R

O

L

7.4b Stereochemistry of the S

N

2 Reaction One of the most powerful of

all tools for investigating the mechanism of a reaction is a stereochemical analysis.

In this case, we need first to see what’s possible and then to design an experiment

CONVENTION ALERT