Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

16.7 Equilibrium in Addition Reactions 779

hydrate. There also appears to be a steric effect. Large alkyl groups favor the

carbonyl compound, as can be seen from the sequence of decreasing equilibrium

constants in Table 16.3: propanal butanal 2,2-dimethylpropanal. Each of these

phenomena can be understood by considering the relative stabilities of the starting

materials and products.

Energy

C

Model acetaldehyde (carbonyl and hydrate

are of comparable stability K ~ 1)

Aldehyde below hydrate

O

CH

3

O

Resonance stabilization of the aromatic aldehyde

[note use of (

+) to show resonance forms]

Hydrate (not stabilized

by resonance)

H

Energy

CH

3

H

H

–

O

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

H

2

O

+

(+)

(+)

C

Cl

O

H

C

Cl

H

C

Cl

H

C

Cl

C

HO

..

..

OH

..

..

H

Cl

HO

HO

..

..

..

..

..

OH

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

C

OH

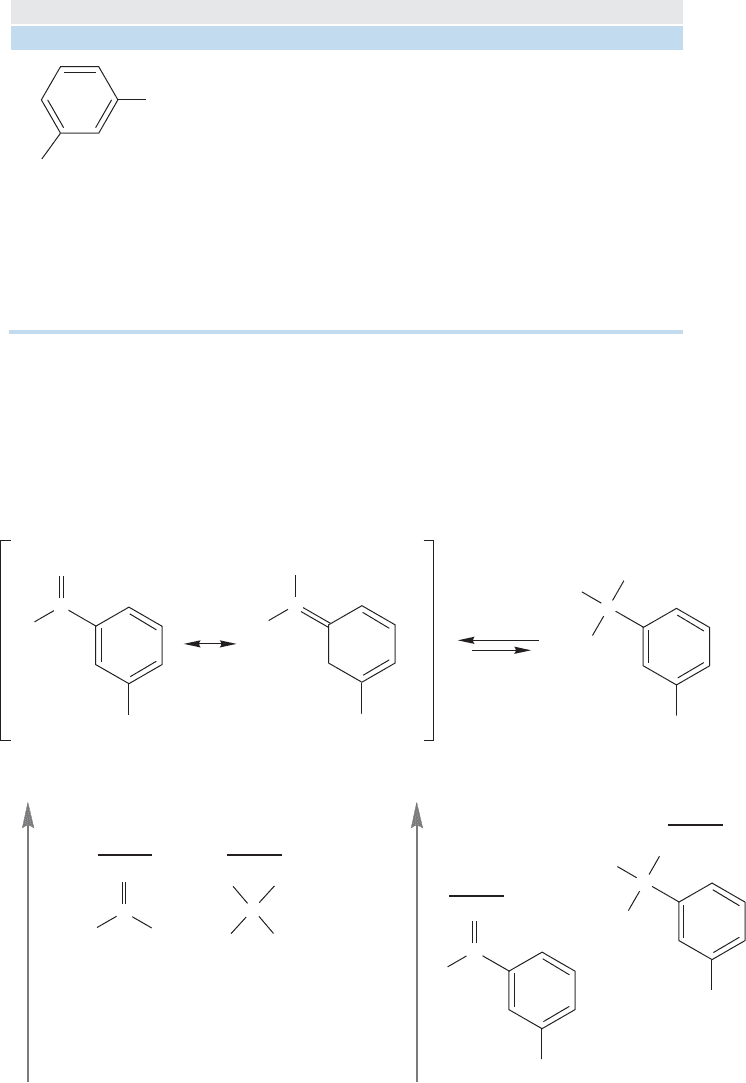

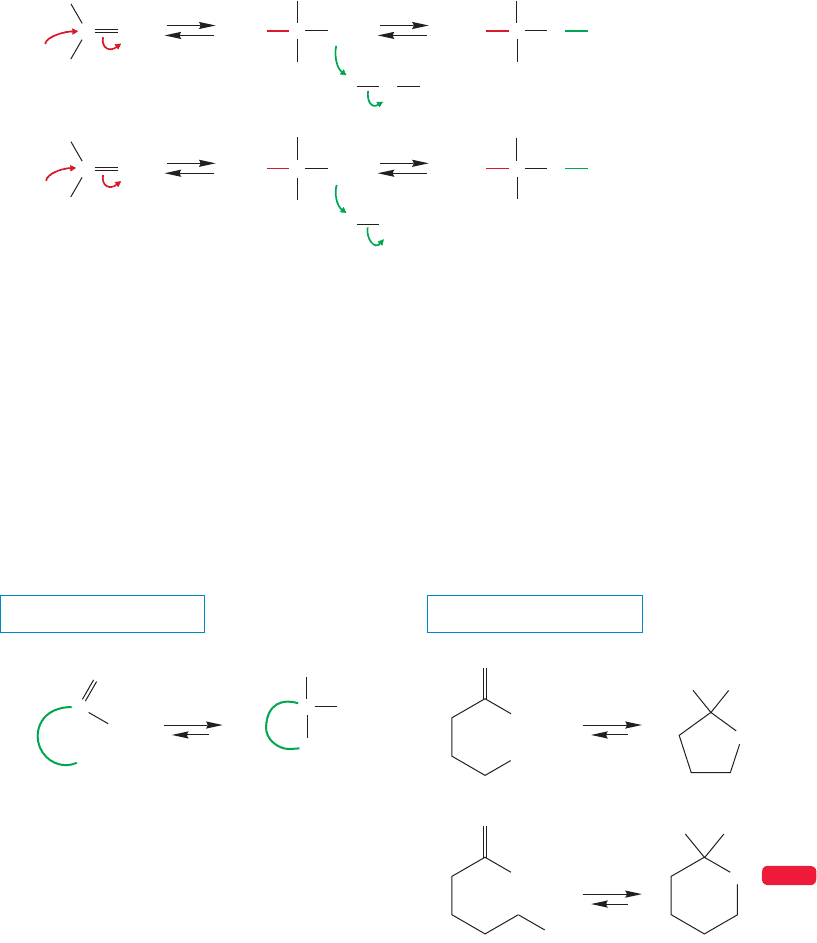

FIGURE 16.30 The aromatic

carbonyl compound is stabilized

by resonance, but the product

hydrate is not. Accordingly, the

carbonyl compound is favored at

equilibrium.

Resonance stabilization of the carbonyl group is generally not accompanied by a

resonance stabilization of the product hydrate (Fig. 16.30). For example, the aromatic

aldehyde, m-chlorobenzaldehyde (Table 16.3), is more strongly stabilized by resonance

than acetaldehyde. There is no corresponding difference in the hydrates, and there-

fore the aromatic aldehyde is less hydrated at equilibrium than acetaldehyde.

TABLE 16.3 Equilibrium Constants for Carbonyl Hydration

Structure Name K

CH

3

CH

2

CHO

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CHO

(CH

3

)

3

CCHO

CF

3

CHO

CCl

3

CHO

ClCH

2

CHO

m-Chlorobenzaldehyde

Propanal

Butanal

2,2-Dimethylpropanal

Trifluoroethanal

Trichloroethanal

Chloroethanal

0.022

0.85

0.62

0.23

2.9 × 10

4

2.8 × 10

4

37

Compound

CHO

Cl

780 CHAPTER 16 Carbonyl Chemistry 1: Addition Reactions

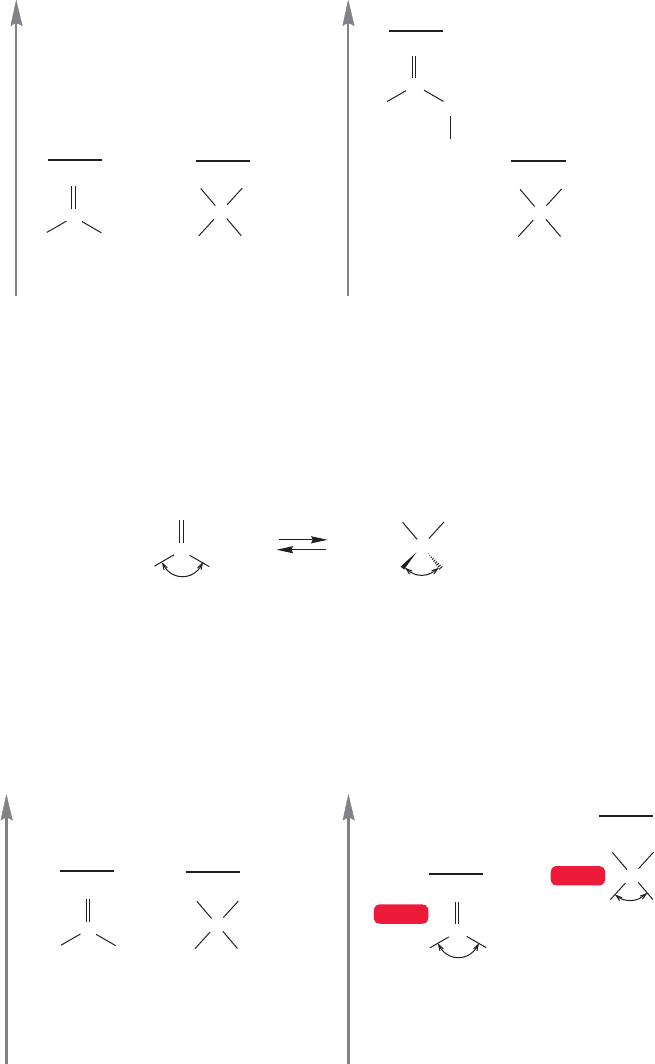

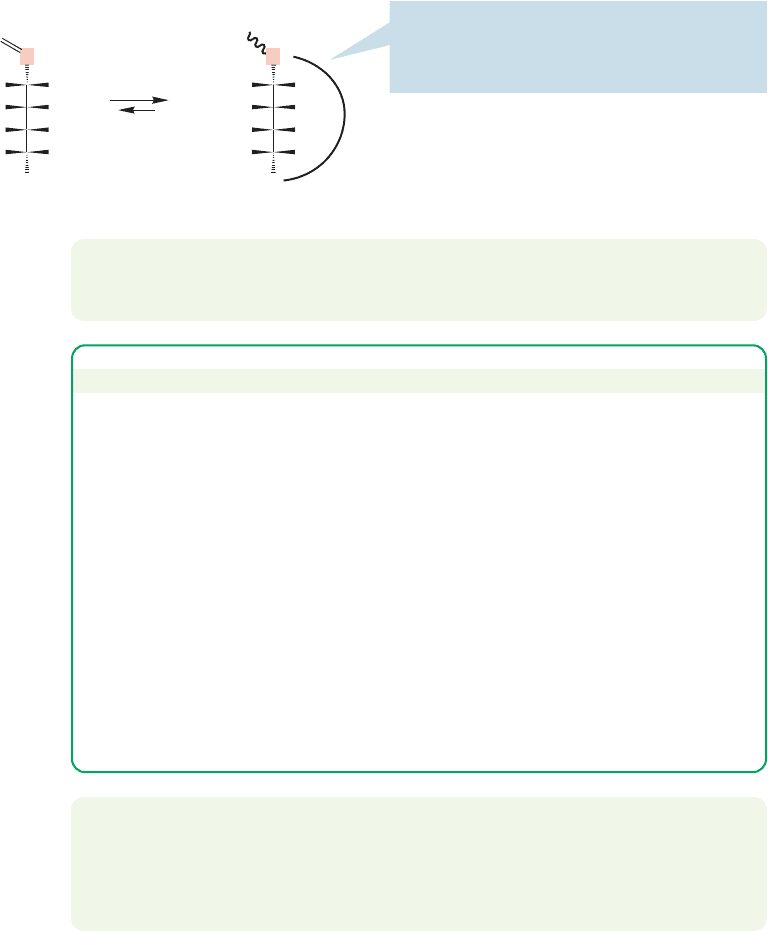

The reason electron-withdrawing groups such as chlorine or fluorine sharply

destabilize carbonyl groups when attached at the α position is that the dipoles oppose

each other. The carbon atom is already electron deficient, and further inductive

removal of electrons by the halogen on the adjacent carbon is costly in energy terms.

There is relatively little effect in the product hydrate, although there is some desta-

bilization in this molecule as well. So, as Figure 16.31 shows, the strong destabiliza-

tion of the carbonyl group favors the hydrate at equilibrium.

Energy

Energy

C

Model acetaldehyde (carbonyl and

hydrate are of comparable stability)

(K ~1)

The inductive effect of the electronegative

chlorine atom destabilizes the aldehyde

relative to the hydrate

O

CH

3 CH

3

H

H

O

H

C

C

HO

..

..

..

OH

..

CH

2

Cl

H

C

HO

..

..

..

OH

..

..

..

CH

2

Cl

..

..

..

..

..

..

δ

+

δ

+

δ

–

δ

–

FIGURE 16.31 Addition of a chlorine

in the α position of acetaldehyde

raises the energy of the carbonyl

compound.

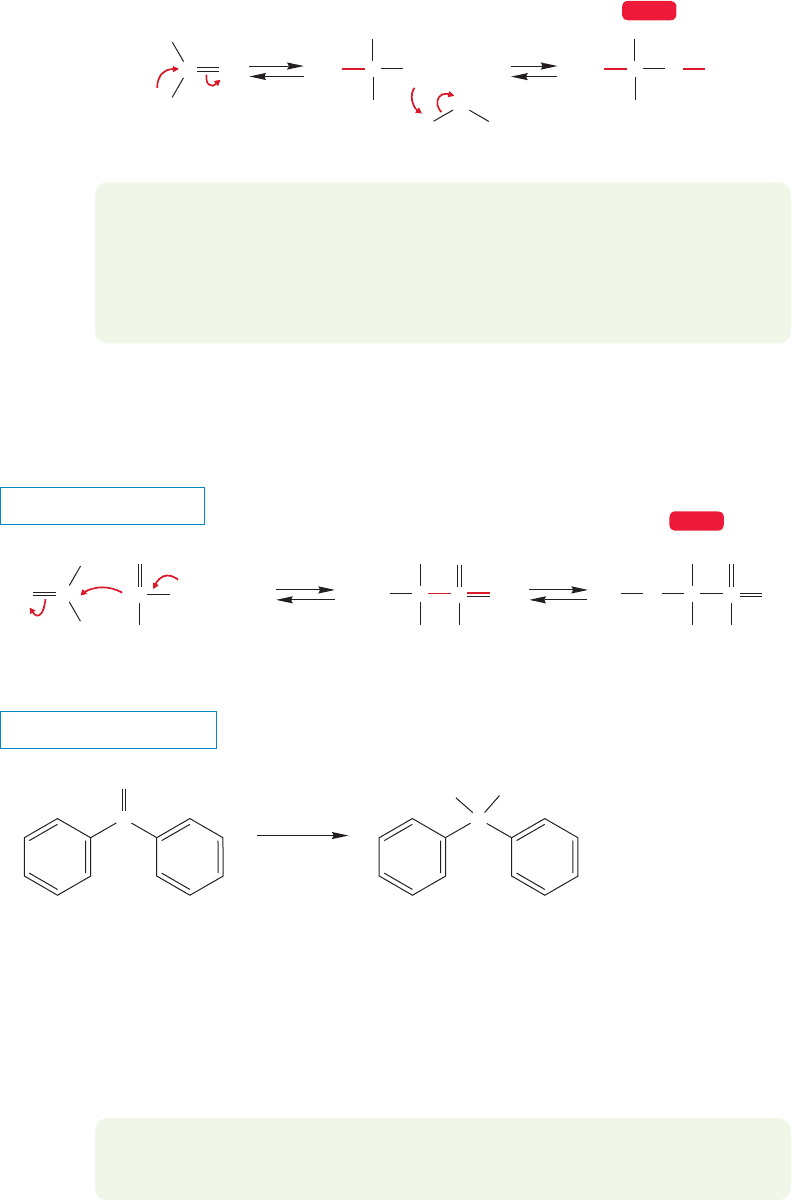

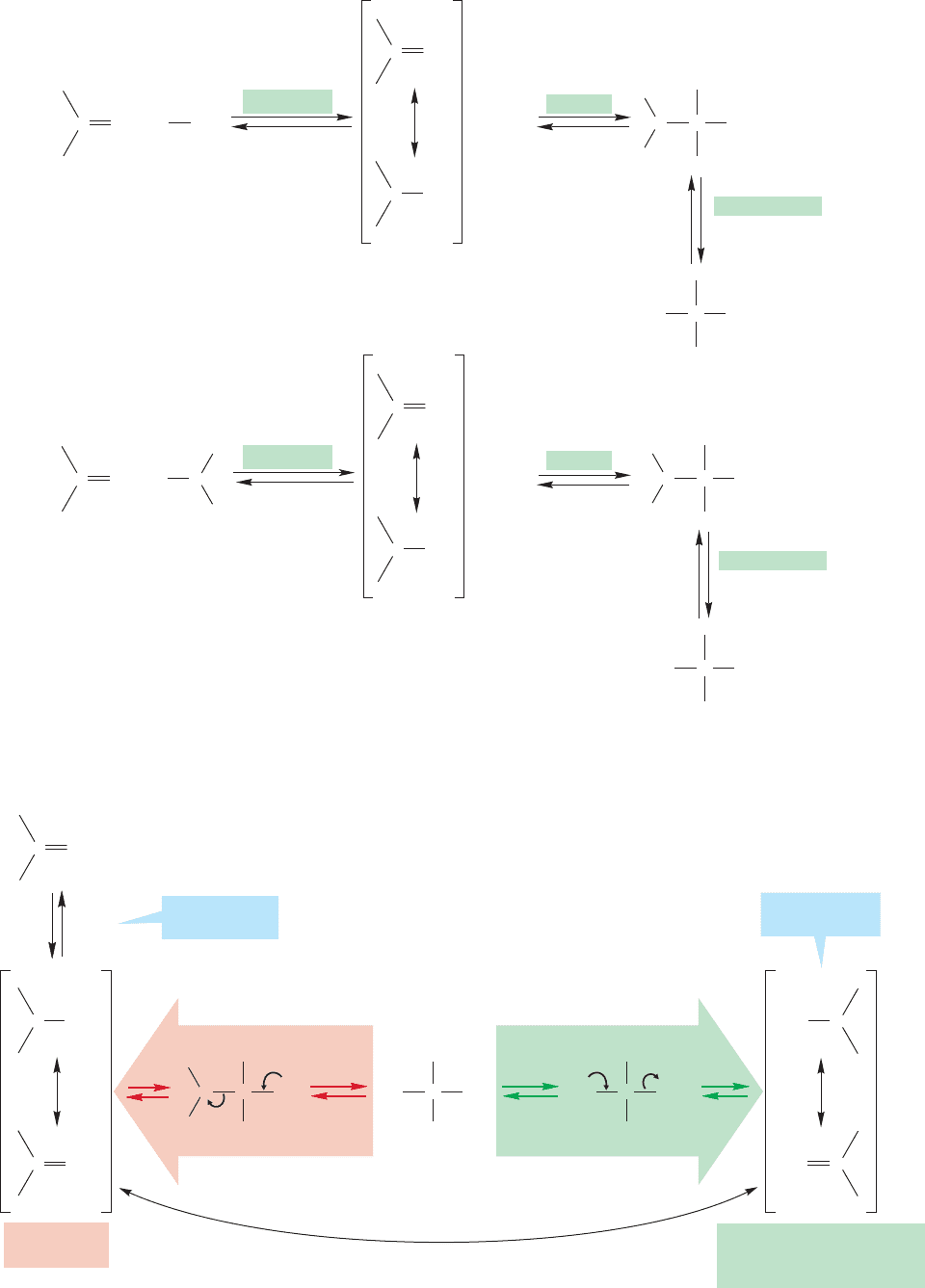

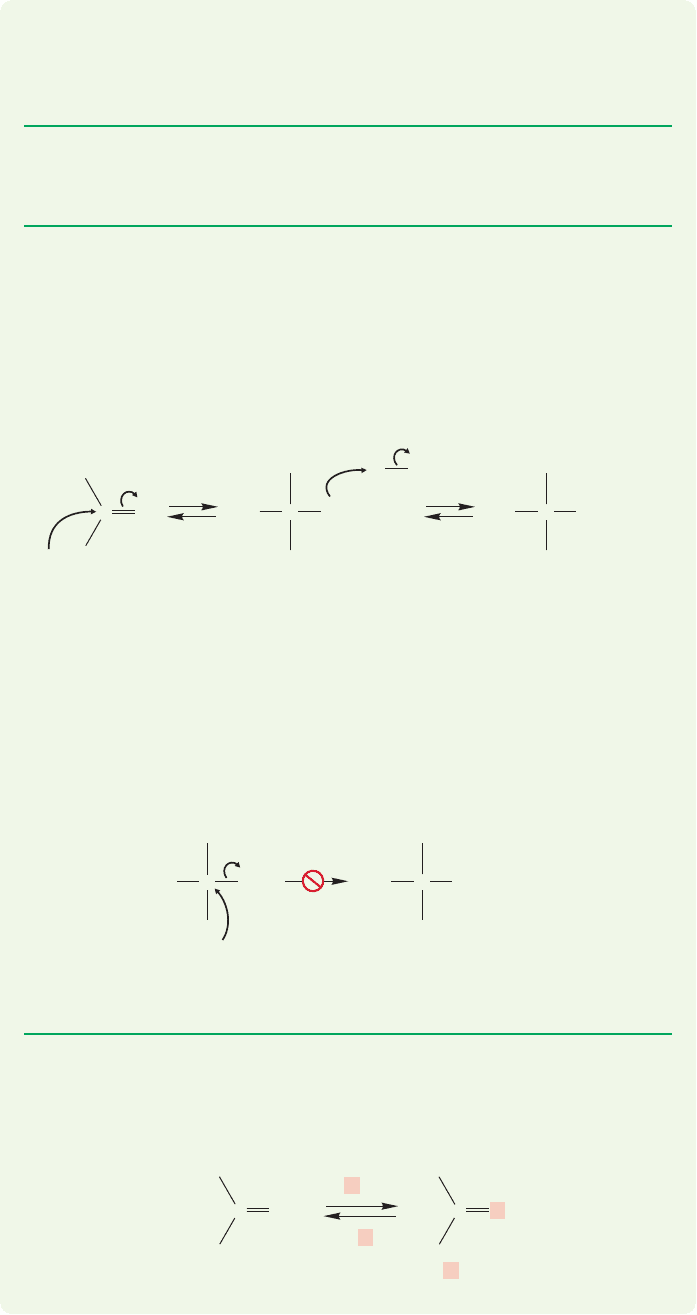

The steric effect is slightly more subtle. In the carbonyl group, the carbon is

hybridized sp

2

and the bond angles are therefore close to 120° (Fig. 16.32). In

the product hydrate, the carbon is nearly sp

3

hybridized, and the bond angles

must be close to 109°. So, in forming the hydrate, groups are moved closer to each

C

O

R

H

R and H are

further apart

R and H are closer together

(destabilizing for large R)

H

R

C

HO OH

~120⬚ ~109⬚

..

..

..

..

....

FIGURE 16.32 In the hydrate, groups

are closer together than they are in

the carbonyl compound.This

proximity destabilizes the hydrate

relative to the carbonyl compound.

Energy

Energy

C

O

H

3

C

H

3

C

H

H

O

(CH

3

)

3

C

C

C

HO

..

..

..

OH

..

(CH

3

)

3

C

H

H

C

HO

..

..

OH

..

..

..

..

..

..

+

..

..

H

2

O

+

..

..

H

2

O

K ~1

K = 0.23

~120⬚

~109⬚

WEB 3D

WEB 3D

FIGURE 16.33 The larger the R

group, the more important the

steric effect. For example, 2, 2-

dimethylpropanal is less hydrated at

equilibrium than is acetaldehyde.

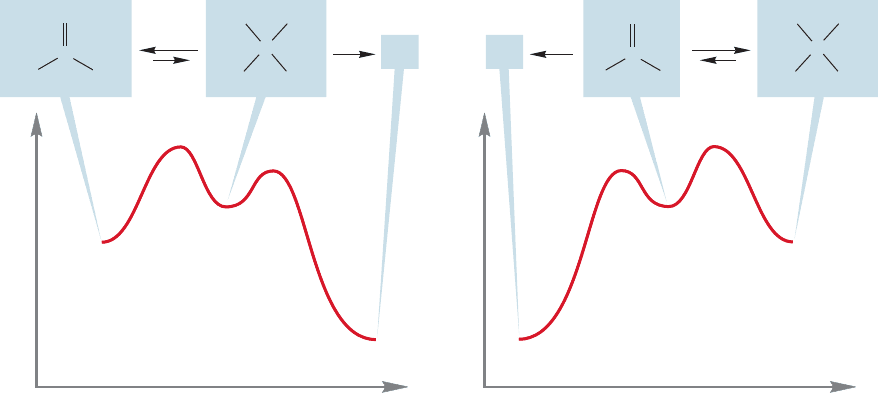

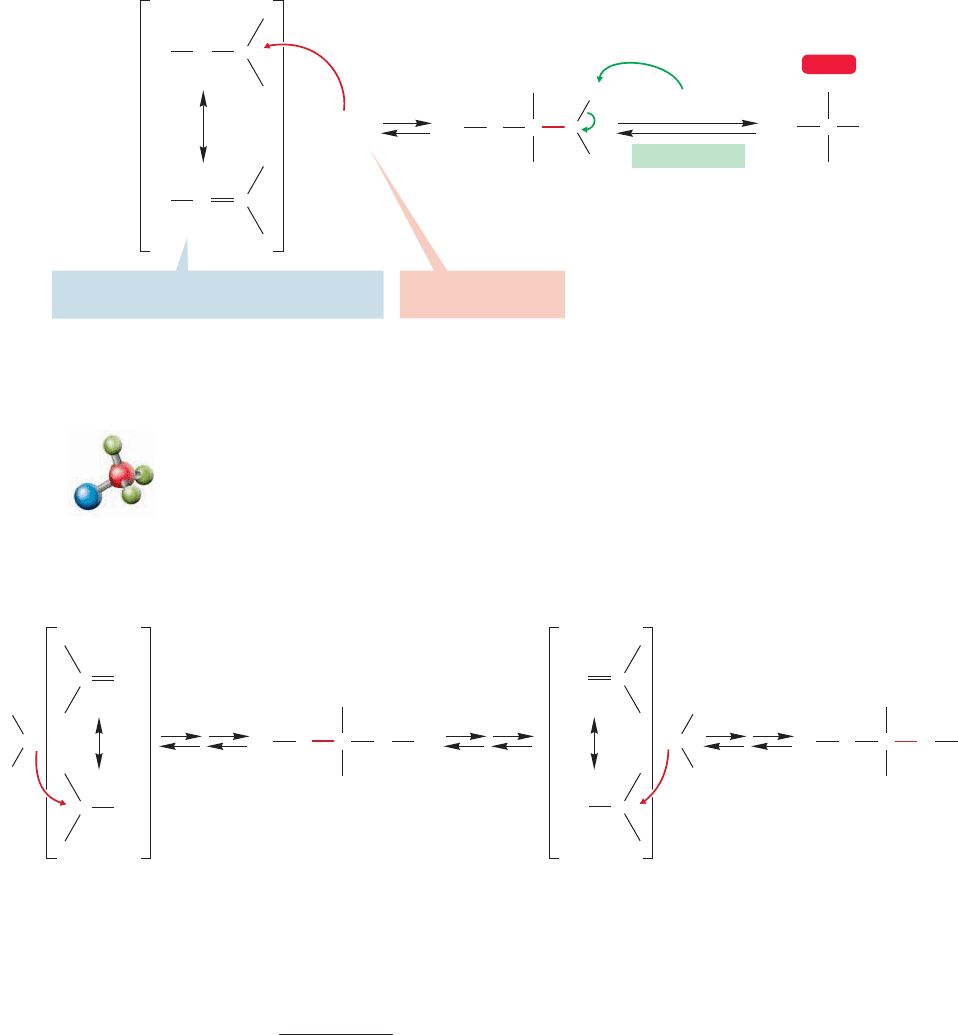

These equilibrium effects are important to keep in mind. Equally important is

the notion that as long as there is some of the higher energy partner present at equi-

librium, it can be the active ingredient in a further reaction.For example, even though

other, and for a large group that is relatively destabilizing. It is less costly in energy

terms to move a methyl group closer to a hydrogen than to move a tert-butyl group

closer to a hydrogen. Accordingly, acetaldehyde is more strongly hydrated than is

2,2-dimethylpropanal (pivaldehyde) (Fig. 16.33).

16.8 Other Addition Reactions: Additions of Cyanide and Bisulfite 781

Energy

Reaction progress

C

O

H

3

C

H

2

O

CH

3

H

3

C

C

X

HO OH

CH

3

Energy

Reaction progress

C

O

H

H

2

O

H

H

C

Y

HO OH

H

Here the unfavored hydrate

leads to product X

Here the unfavored carbonyl

compound leads to product Y

(a) (b)

FIGURE 16.34 Molecules not favored at equilibrium may nonetheless lead to products.These two examples show a

pair of carbonyl compound–hydrate equilibria in which it is the higher energy, unfavored partner that leads to product.

As the small amount of the higher energy molecule is used up, equilibrium is reestablished and more of the unfavored

compound is formed. (a) Reaction of the acetone hydrate is possible even though the hydrate is not the favored species.

(b) Reaction of the formaldehyde carbonyl group is possible even though the carbonyl is not the favored species.

As usual,mechanisms stick in the mind most securely if we are able to write them

backward.“Backward”is an arbitrary term anyway, because by definition an equilib-

rium runs both ways. Carbonyl addition reactions are about to grow more complex,

and you run the risk of being overwhelmed by a vast number of proton additions

and losses in the somewhat more complicated reactions that follow. Be sure you are

completely comfortable with the acid-catalyzed and base-catalyzed hydration reac-

tions in both directions before you go on. That advice is important.

it is a minor component of the equilibrium mixture (Fig.16.34a), the hydrate of ace-

tone could go on to other products (X), with more hydrate being formed as the small

amount present at equilibrium is used up. Similarly, even though it is extensively

hydrated in aqueous solution, reactions of formaldehyde to give Y can still be

detected (Fig.16.34b).It is also worth mentioning that gem-diols (hydrates) are very

difficult to isolate.Even though we know they exist in aqueous environment,in order

to isolate the diol we must remove the water and that drives the equilibrium toward

the carbonyl species.

16.8 Other Addition Reactions: Additions

of Cyanide and Bisulfite

Many other addition reactions follow the pattern of carbonyl hydration. Two typical

examples are cyanohydrin formation and bisulfite addition. Both of these reactions are

generally base catalyzed.Because of an understandable and widespread aversion to work-

ing with the volatile and notorious HCN, cyanide additions are generally carried out

with cyanide ion.Potassium cyanide (K

CN) is certainly poisonous,but it’s not volatile,

and one knows where it is at all times,at least as long as basic conditions are maintained.

782 CHAPTER 16 Carbonyl Chemistry 1: Addition Reactions

Cyanide ion is a good nucleophile and attacks the electrophilic carbonyl compound

to produce an alkoxide (Fig. 16.35). This alkoxide is protonated by solvent, often

water, to give the final product, a cyanohydrin. The cyanohydrin is often not stable

under basic conditions and reverses to the carbonyl compound and cyanide.

PROBLEM 16.9 Why does acetaldehyde in aqueous solution form an excellent

yield of cyanohydrin even though acetaldehyde is substantially hydrated in water

(K 1)? Might it not be argued that, because about one-half of the aldehyde is

present in hydrated form at equilibrium, no more than about 50% cyanohydrin

can be formed. Why is this argument wrong? Hint: See Figure 16.34.

'

–

C C

O

..

..

..

O

..

..

..

..

NC

..

NC

..

NC

–

C

O

..

..

O

..

..

A cyanohydrin

H

HH

–

OH

..

..

..

K

+

K

+

K

+

WEB 3D

FIGURE 16.35 Cyanohydrin formation.

Bisulfite addition to an aldehyde or ketone is similar to cyanide addition,although

the nucleophile in this case is sulfur. Sodium bisulfite adds to many aldehydes and

ketones to give an addition product, often a nicely isolable solid (Fig. 16.36).

OH OH

..

..

O

..

..

..

..

NaHSO

3

H

2

O

(98%)

HO

SO

3

Na

–

S

O

..

..

..

..

O

..

..

S

O

..

..

O

..

..

C

H

R

O

..

..

..

O

..

..

S

O

..

..

O

..

..

C

H

H

R

H

R

–

–

O

..

..

..

Na

+

Na

+

Na

+

C

C C

O

THE GENERAL CASE

A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

WEB 3D

FIGURE 16.36 Bisulfite addition.

The reactions we have seen so far have all been simple additions of a generic HX

to the carbon–oxygen bond of a carbonyl group. Now we move on to related reac-

tions in which there is one more dimension. In these new reactions, addition of HX

is accompanied by the loss of some other group.

PROBLEM 16.10 Bisulfite addition is generally far less successful with ketones than

it is with aldehydes. Explain why.

16.9 Addition Reactions Followed by Water Loss: Acetal Formation 783

16.9 Addition Reactions Followed by Water Loss:

Acetal Formation

If aldehydes and ketones form hydrates in water ( ), shouldn’t there be a

similar reaction in the presence of alcohols ( )? Indeed there should be,

and there is. However, the reactions are slightly more complicated than simple

hydration, at least under acidic conditions. In base, the two reactions are entirely

analogous, so let’s look at that reaction first.

Figure 16.37 contrasts the base-catalyzed reaction of a carbonyl compound in

water to give a hydrate with the related formation of a hemiacetal in an alcohol.

The hemiacetal is similar to a gem-diol, except that the central carbon has an OH

and an OR group rather than two OH groups.

R

O

OH

H

O

OH

–

C C

O

..

..

..

O

..

..

O

..

..

Hydrate

H

H

–

OH

..

..

..

–

HO

..

..

CH

O

..

..

HO

..

..

HO

..

..

..

+

–

C C

O

..

..

..

O

..

..

OR

..

..

Hemiacetal

H

–

OR

..

..

..

–

RO

..

..

CH

O

..

..

RO

..

..

RO

..

..

..

+

FIGURE 16.37 The reaction of a

carbonyl group with hydroxide ion

in water parallels the reaction of a

carbonyl with an alkoxide ion in

alcohol. In water, a gem-diol (or

hydrate) is formed; in alcohol, the

analogous product is called a

hemiacetal.

OH

..

..

OH

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

O

..

..

O

..

(88.6%)(11.4%)

(93.9%)(6.1%)

C

H

H

Open-chain

hydroxy–aldehyde

Cyclic

hemiacetal

C

OH

H

O

OH

H

O

O

O

H

HO

H

HO

THE GENERAL CASE

SPECIFIC EXAMPLES

WEB 3D

H

2

O H

2

O

H

2

O

FIGURE 16.38 Cyclic hemiacetals are often more stable than their open-chain counterparts.

Hydration and hemiacetal formation are comparable, so it is no surprise that

the discussion in Section 16.7 on equilibrium effects is quite directly transferable to

this reaction. Aldehydes, for example, are largely in their hemiacetal forms in basic

alcoholic solutions (in acid the reaction goes further, as we will see), whereas ketones

are not.

Most simple hemiacetals, like gem-diols, are not isolable. However, the cyclic

versions of these compounds often are. Consider combining the carbonyl and

hydroxyl components of the hemiacetal reaction in Figure 16.37 within the same

molecule (Fig. 16.38). Now hemiacetal formation is an intramolecular process. If

the ring size is neither too large nor too small, the hemiacetals are often more sta-

ble than the open-chain molecules.

784 CHAPTER 16 Carbonyl Chemistry 1: Addition Reactions

Now, what about the acid-catalyzed version of the reaction of alcohols and alde-

hydes or ketones? The process begins with hemiacetal formation, and the mecha-

nism parallels that of acid-catalyzed hydration (Fig. 16.25b). A three-step sequence

of protonation, addition, and deprotonation occurs in each case (Fig. 16.40).

Can anything happen to a hemiacetal in acidic solution? Does the reaction stop there?

One thing you know happens is the set of reactions indicated by the reverse arrows in

the equilibria of Figure 16.40.In this case, the oxygen atom of the OR is protonated and

an alcohol molecule is lost to give the resonance-stabilized protonated carbonyl com-

pound.This intermediate is deprotonated to give the starting ketone or aldehyde.There

is no need for us to write out the mechanism because it already appears exactly in the

reverse steps of Figure 16.40. It is simply the forward reaction run directly backward.

PROBLEM SOLVING

Problems that ask you to write a mechanism for the transformation of a starting

material into a product are common,and they will appear increasingly throughout the

remaining chapters.This particular problem should be relatively easy, but it serves as

an example of how to analyze what must happen.That kind of analysis is absolutely

critical to success in solving hard mechanistic problems. It is very, very important to

get into the habit right now of defining goals in mechanism problems. For example,

in the first part of this problem, what happens? A carbon–oxygen bond is made. A

carbonyl group becomes an alcohol. So, we have two goals (write them down!):

1. Close the ring by making a bond.

2. Break the double bond.

It is easy to see that the two goals are connected—this is an easy problem—but

defining and paying attention to those goals is critical practice, and a great habit

to get into.

C

P

O

C

O

O

HOCH

2

The sugar, D-glucose

H

H

H

H

OH

OH

OH O

Open form

HO

O

CH

HOCH

2

H

H

H

H

OH

OH

Cyclic hemiacetal form

HO

HO

CH

Watch out, there is a convention at work here;

there is no “corner” in the oxygen bridge; sugar

chemists have learned to reinterpret the long

curved bond in the bottom part of the structure

FIGURE 16.39 Sugars exist mainly

in their cyclic hemiacetal forms.

The most spectacular examples of this effect are the sugars, polyhydroxylated

compounds that exist largely, though not quite exclusively, in their cyclic hemiacetal

forms (Fig. 16.39). We will explore the chemistry of sugars in Chapter 22.

PROBLEM 16.11 Write a mechanism for the intramolecular formation of one of the

hemiacetals of Figure 16.38.

PROBLEM 16.12 Note how odd the cyclic structure in Figure 16.39 looks.

Construct a three-dimensional picture of

D-glucose that better represents its

structure in the cyclic hemiacetal form. Note that the position of the OH on the

carbon marked in red in Figure 16.39 can be either axial or equatorial.

16.9 Addition Reactions Followed by Water Loss: Acetal Formation 785

H

2

O

..

..

O

C

O

..

..

..

..

C

..

H

OH

2

H

H

COH

..

..

HO

..

..

Hydrate

COH

..

..

COH

..

..

..

HO

..

..

+

+

+

H

2

O

+

+

..

OH

+

C

..

..

OH

+

Hydration reaction in acid

addition

protonation

deprotonation

H

3

O

..

+

FIGURE 16.40 The acid-catalyzed

formation of a hemiacetal parallels

the acid-catalyzed hydration reaction.

But suppose it is not the OR oxygen that is protonated, but

instead the OH oxygen? Surely, if one of these reactions is

possible, so is the other. If we keep strictly parallel to the

reverse process, we can now lose water to give a resonance-

stabilized species (Fig. 16.41), which is quite analogous to the

COH

..

..

RO

..

..

Hemiacetal

COH

..

..

....

..

COH

2

..

RO

..

..

C

..

..

..

RO

..

..

..

..

+

+

C

..

OH

+

C

..

..

OH

+

C

..

..

O

A protonated

carbonyl

This resonance-stabilized

intermediate is analogous

to the protonated carbonyl

ROH

..

..

ROH

2

..

+

ROH

2

..

+

O

R

H

COH

+

C

+

RO

....

C

+

+

ROH

2

..

+

No proton on

oxygen to lose!

Deprotonation

step

Protonation of the OR

Protonation of the OH

..

..

H

2

O

FIGURE 16.41 Protonation of the OH in

the hemiacetal, followed by water loss,

leads to a resonance-stabilized species that

is analogous to the protonated carbonyl.

..

..

..

..

..

..

Hemiacetal formation in acid

addition

protonation

HOR

..

..

HOR

..

..

..

O

C

H

R

O

..

..

O

..

C

H

H

R

COH

RO

Hemiacetal

COH

COH

+

+

H

2

OR

..

+

deprotonation

+

+

+

..

OH

+

C

..

..

OH

+

786 CHAPTER 16 Carbonyl Chemistry 1: Addition Reactions

Notice that the second addition of alcohol in acetal formation is just like the first;

the only difference is the presence of an H or R group in the species to be attacked

(Fig. 16.43). Notice also that acetal formation is completely reversible.

..

..

..

..

C

+

RO

RO

....

C

+

CO

..

..

O R R

..

..

C

..

..

R

H

First alcohol addition Second alcohol addition

CO

..

..

O

..

..

CHR

..

..

C

..

OH

+

C

..

..

OH

+

O

R

H

Resonance-stabilized

intermediate

(a protonated carbonyl)

Hemiacetal Acetal

Resonance-stabilized

intermediate (R

replaces H)

..

..

O

..

..

FIGURE 16.43 The two alcohol additions that occur in acetal formation are very similar to each other.

resonance-stabilized protonated carbonyl compound of Figure 16.40. But now depro-

tonation is not possible—there is no proton on oxygen to lose. Another reaction occurs

instead,the addition of a second molecule of alcohol.Deprotonation gives a full acetal

2

(Fig.16.42).An acetal contains an sp

3

hybridized carbon that has two OR groups attached.

An acetal

ROH

..

..

O

..

..

..

..

+

C

+

O

R

R

R

....

C

+

This species cannot lose a proton to

regenerate the carbonyl compound, so…

…addition of a

second HOR occurs

HOR

..

..

+

..

..

..

O

H

R

C

+

COR

..

..

RO

..

..

C

..

..

O

deprotonation

ROH

2

..

+

WEB 3D

FIGURE 16.42 An acetal is formed by addition of a second molecule of alcohol to the resonance-stabilized intermediate.

2

Organic chemists originally used hemiketal and ketal for describing the products from alcohol addition to

ketones; and hemiacetal and acetal were used for the products from alcohol addition to aldehydes.The IUPAC

system has dropped the hemiketal and ketal names in favor of using hemiacetal and acetal for the species formed

from both aldehydes and ketones. We will not use hemiketal or ketal, but be alert, because one still sees these

sensible terms occasionally.

Acetal formation

16.9 Addition Reactions Followed by Water Loss: Acetal Formation 787

PROBLEM 16.13 Write the mechanism for the formation of the acetal from

treatment of cyclopentanone in ethylene glycol (1,2-ethanediol) with an acid

catalyst.

PROBLEM 16.14 Write the mechanism for the reverse reaction, the regeneration of

the starting ketone on treatment of the acetal with aqueous acid.

WORKED PROBLEM 16.15 Explain why hemiacetals, but not full acetals, are formed

under basic conditions.

ANSWER If we work through the mechanism we can see why. The first step is

addition of an alkoxide to the carbonyl group to form the alkoxide intermediate.

Protonation then gives the hemiacetal and regenerates the base.

..

..

O

..

..

..

RO

C

..

..

..

O

..

..

RO

..

..

OR

H

HemiacetalAlkoxide

C

..

..

OH +

..

..

RO

C

–

–

..

..

..

OR

–

..

..

RO

C

..

..

OR

..

..

OH +

..

..

RO

C

..

..

..

OH

..

..

RO

–

–

PROBLEM 16.16 When acetone is treated with

18

OH

2

/

18

OH

3

, acetone is found to

be labeled with

18

O. Explain.

O

C

..

..

O

C

..

..

O =

18

O

..

..

OH

2

H

3

O

..

+

Now what? There is no acid available to protonate the OH oxygen. In order to

get an acetal, RO

must displace hydroxide! This reaction is most unfavorable.

The more favorable reaction between RO

and the hemiacetal is removal of the

proton to re-form the intermediate alkoxide. In base, the reaction cannot go

beyond hemiacetal formation.

788 CHAPTER 16 Carbonyl Chemistry 1: Addition Reactions

excess ROH

acid catalyst

acid catalyst

excess H

2

O

CH

3

OH

2

CH

3

OH

+

+

O

C

X

C

X

OR

OR

C

Y

OR

OR

base

O

Desired conversion

C

Y

O

C

Y

chemistry

An acetal (stable in base);

the carbonyl group is

protected, or masked

Here the C

O

is unmasked

(regenerated)

O

A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

THE GENERAL CASE

O

CH

3

O OCH

3

H

2

/Pd H

3

O

H

2

O

CH

3

O OCH

3

FIGURE 16.44 A protecting group

can be used to mask a sensitive

functional group while reactions are

carried out on other parts of the

molecule. When these reactions are

completed, the original functionality

can be regenerated.

Summary

By now, you may be getting the impression that almost any nucleophile will add to

carbonyl compounds. If so, you are quite right. So far, we have seen water, cyanide,

bisulfite, and alcohols act as nucleophiles toward the Lewis acidic carbon of the car-

bon–oxygen double bond.Addition can take place under neutral,acidic,or basic con-

ditions. All of the addition reactions are similar, with only the details being different.

Those details are important though, as well as highly effective at camouflaging the

essential similarity of the reactions.We’ll now see some examples of acetal chemistry.

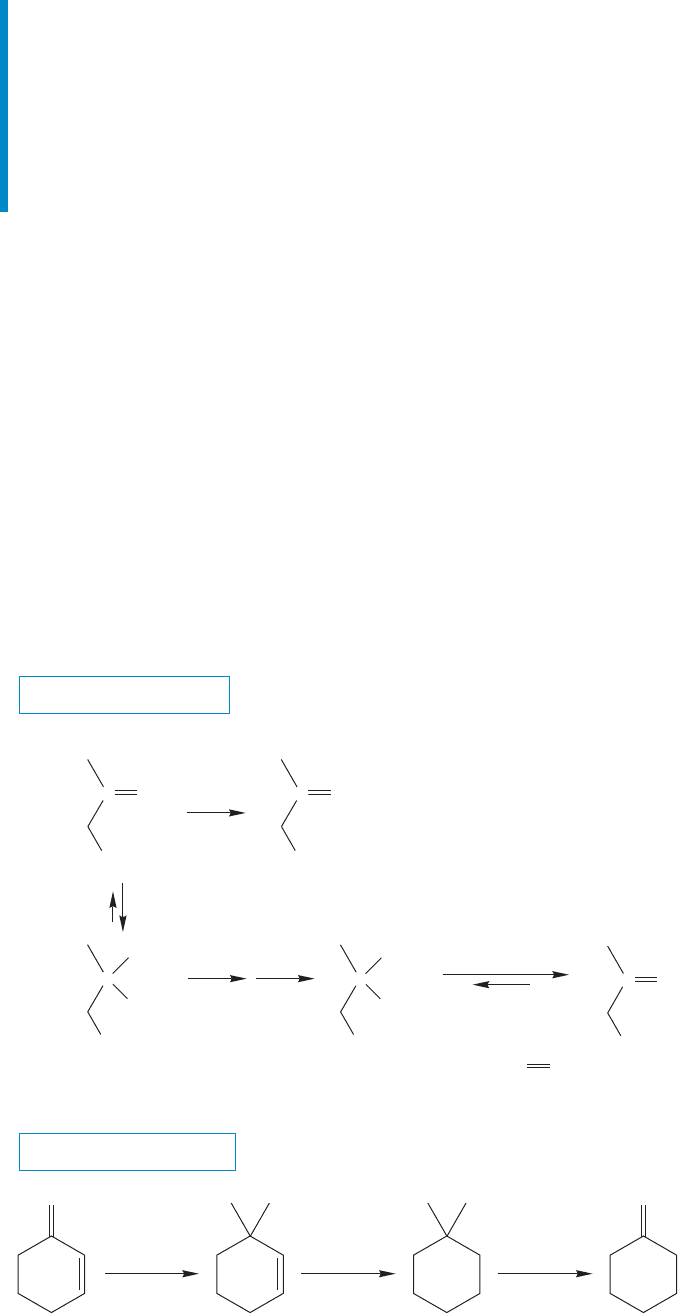

16.10 Protecting Groups in Synthesis

16.10a Acetals as Protecting Groups for Aldehydes and Ketones

By all means work out the mechanism of acetal formation by setting yourself the

problem of writing the mechanism for the reverse reaction (go back and do

Problem 16.14!), the formation of a ketone or aldehyde from the reaction of an

acetal in acidic water. Acetal formation is an equilibrium process, and conditions

can drive the overall equilibrium in the forward or backward direction. In an

excess of alcohol, an acid catalyst will initiate the formation of the acetal, but in

an excess of water, that same acid catalyst will set the reverse reaction in motion,

and we will end up with the carbonyl compound. This point is important and

practical. Carbonyl compounds can be “masked,” stored or protected, by convert-

ing them into their acetal forms, and then regenerating them as needed. The

acetal constitutes your first protecting group. For example, it might be desirable

to convert group X, in the carbonyl-containing molecule shown in Figure 16.44,