Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CANCERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

419

cases of cancer started in the eighteenth century. The word cancer

comes from the Latin ‘‘cancer-cancri’’ and the Greek karkinos (used

by Hippocrates in the fifth century B.C.), meaning both cancer and

crab. The two words are linked via images of creeping, voracity, and

obliqueness. Just like crabs, cancers creep inside the organism and eat

away at it. The association of cancers and crabs has lasted throughout

the centuries: Rudyard Kipling used the expression ‘‘Cancer the

Crab,’’ and an American cartoon booklet from the 1950s shows a

giant crab crushing its victims with its huge pincers, the words

‘‘Cancer the killer’’ appearing above the scene. Adopting a typically

apocalyptic mood, Michael Shimkin claimed that American citizens

had defeated the ‘‘pale rider of pestilence’’ and the ‘‘cadaverous rider

of hunger,’’ but that they now had to face two different riders—‘‘one

in shape of a mushroom cloud and one in the shape of a crab’’.

In the United States, cancer made its first big public appearance

with the illness and death in 1884-1885 of the national hero who had

led the Union troops to victory in the Civil War: Ulysses S. Grant.

Public use of the word cancer, as James Patterson has pointed out, had

been uncommon until then. Grant’s cancer received exceptional

newspaper coverage and the readers of the age were fascinated by it.

Unofficial remedies and healers came to the forefront, positing for the

first time what would be a recurrent dichotomy in the history of cancer

research: the orthodox medicine of the ‘‘cancer establishment’’

versus the unorthodox medicine of the ‘‘cancer counter-culture.’’

Cancer, with its slow but unrelenting progression, seemed the very

denial of several developments taking place during the late nineteenth

century (such as higher life expectancy and economic growth) which

contributed to the people’s perception of the United States as the land

of progress and opportunity for a well-to-do life. The denial of death

played an important part in this quest for a well-to-do life, and James

Patterson explains that this particular attitude ‘‘account[s] for many

responses to cancer in the United States during the twentieth century,

including a readiness to entertain promises of ‘magic bullets.’ In no

other nation have cancerphobia and ‘wars’ against cancer been more

pronounced than in the United States.’’ Since the late 1970s, the war

on cancer has been coupled with a fierce battle against smoking

(which medical specialists have singled out as the main cause of lung

cancer), a battle featuring scientific researchers pitted against tobacco

lobbies and their powerful advertising experts.

Military metaphors have been widely used in the battle against

cancer. One of the posters of the American Society for Control of

Cancer from the 1930s urges us to ‘‘fight cancer with knowledge’’;

the message appears below a long sword, the symbol of the Society.

As part of the growing pressure for a national war on the disease

during the 1960s, cancer activists asked for more money to be devoted

to research and prevention by claiming that cancer was worse than the

Vietnam War; the latter had killed 41,000 Americans in four years,

while the former had killed 320,000 in a single year. Nixon was the

first president of the United States to declare war on cancer. In

January 1971, he declared in his State of the Union message that ‘‘the

time has come when the same kind of concentrated effort that split the

atom and took the man on the moon should be turned toward

conquering this dread disease.’’ Later in the same year, two days

before Christmas, Nixon signed the National Cancer Act (which

greatly increased the funds of the National Cancer Institute, or NCI)

and called for a national crusade to be carried out by 1976, the two

hundredth anniversary of the birth of the United States. And yet this

program revealed itself to be too optimistic and the association of

cancer and Vietnam reappeared. People started to compare the

inability of the NCI to deliver a cure to the disastrous outcome of the

Vietnam War. Dr. Greenberg, a cancer researcher, declared in 1975

that the war on cancer was like the Vietnam War: ‘‘Only when the

public realized that things were going badly did pressure build to get

out.’’ Gerald Markle and James Petersen, comparing the situation to

the fight against polio, concluded that ‘‘the war on cancer is a

medical Vietnam.’’

The military rhetoric of wars and crusades has also been applied

to drugs, poverty, and other diseases in our society. Susan Sontag has

claimed that military metaphors applied to illnesses function to

represent them as ‘‘alien.’’ Yet the stigmatization of cancer leads

inevitably to the stigmatization of the patients as well. Many scientific

attempts to explain the causes of cancer implicitly blame patients. As

late as the 1970s, Lawrence LeShan and Carl and Stephanie Simonton

claimed that stress, emotional weakness, self-alienation, depression,

and consequent defeatism were the distinctive features of a ‘‘cancer

personality’’ and could all be causes of cancer. Sontag maintained

that the theory that there was ‘‘a forlorn, self-hating, emotionally inert

creature’’ only helped to blame the patient. This particular focus on

stress was also based on a traditionally American distrust of modern

industrialized civilization and urban life, which were to be blamed for

the intensification of the pace of living and the consequent rise in

anxiety for human beings. The wide circulation of these ideas pointed

to popular dissatisfaction with most official medical explanations of

cancer. Not surprisingly, cancer itself has become a powerful meta-

phor for all that is wrong in our society. Commentators often talk

about the cancer of corruption effecting politics or about the spread-

ing cancer of red ink in the federal budget. No other disease has

provided metaphors for such a wide range of social and economic issues.

‘‘Cancerphobia’’ has been a constant source of inspiration for

popular literature, cinema, and television. While cancer was mainly a

disease for supporting actors (Paul Newman’s father in Cat on a Hot

Tin Roof, 1958) in the 1950s and 1960s, since the 1970s cancer

movies have often served as vehicles for stars such as Ali McGraw

and Ryan O’Neal in Love Story (1970), James Caan in Brian’s Song

(1972), Debra Winger in Terms of Endearment (1983), Julia Roberts

in Dying Young (1991), Jack Lemmon in Dad (1989), Tom Hanks and

Meg Ryan in Joe Versus the Volcano (1990), Michael Keaton in My

Life (1993), and Susan Sarandon and Julia Roberts in Stepmom

(1998). Most of these few-days-to-live-stories are melodramatic,

tear-jerking accounts of cancer which rely on the popular perception

of the illness as mysterious and deceiving. In Terms of Endearment,

Debra Winger discovers she has cancer almost by chance and dies

shortly after having declared that she feels fine. In Dad, Jack

Lemmon’s cancer disappears, giving everyone false hopes, only to

reappear fatally after a short while. These stories are often told with a

moralizing intent: cancer is perceived as providing opportunities for

the redemption of the characters involved in the drama—in Terms of

Endearment, Winger and her husband Jeff Daniels, who have both

been unfaithful, reconcile at her deathbed; in Dad, cancer brings Jack

Lemmon and his son Ted Danson closer together after years of

estrangement; and in Stepmom the disease rekindles female bonds

that had been obscured by misunderstandings and rivalries over men.

And in Love Story and Dying Young, cancer serves as the medium

through which two young people from different economic back-

grounds are brought together despite their parents’ opposition.

The (melo)drama of cancer in American culture is characterized

by an enduring dichotomy of hope and fear. The official optimism for

a cure, such as that placed in the 1980s on interferon, a protein able to

stop the reproduction of cancerous cells, has always been countered

by obstinate popular skepticism. Medical progress has been unable to

CANDID CAMERA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

420

discourage popular faith in unorthodox approaches to the disease. On

the contrary, as James Patterson has argued, popular skepticism has

often been fostered by ‘‘the exaggerated claims for science and

technological medicine’’ and still makes cancer retain its malignant

grip on the American popular imagination as ‘‘an alien, surreptitious,

and voracious invader.’’

—Luca Prono

F

URTHER READING:

LeShan, Lawrence. You Can Fight For Your Life: Emotional Factors

in the Causation of Cancer. New York, M. Evans & Co., 1977.

Markle, Gerald, and James Petersen, editors. Politics, Science and

Cancer. New York, AAAS, 1980.

Patterson, James T. The Dread Disease: Cancer and Modern Ameri-

can Culture. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1987.

Shimkin, Michael. Science and Cancer. Bethesda, Maryland, Nation-

al Institute of Health, 1980.

Simonton, Carl and Stephanie. Getting Well Again. Los Angeles, J.P.

Tarcher, 1978.

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. New York, Farrar, Strauss, and

Giroux, 1978.

Candid Camera

As a television show, Candid Camera enjoyed immense popu-

larity with American viewers at mid-twentieth century even as it

fundamentally changed the way in which Americans perceived be-

havior on the television screen and their own vulnerability to being

observed. The catch phrase ‘‘candid camera’’ had been current in

American English by the 1930s, thanks to the development of fine-

grained, high-speed films which made spontaneous picture-taking of

unselfconscious subjects a staple of news and backyard photogra-

phers alike, freeing them from the constraints of long exposures and

conspicuously large apparatus. But it was Allen Funt’s brash se-

quences of ordinary people caught unawares on film that made

‘‘candid camera’’ synonymous with uninhibited surveillance of our

unguarded moments, whether for the amusement of the studio audi-

ence or the more sinister purposes of commercial and state-

sponsored snooping.

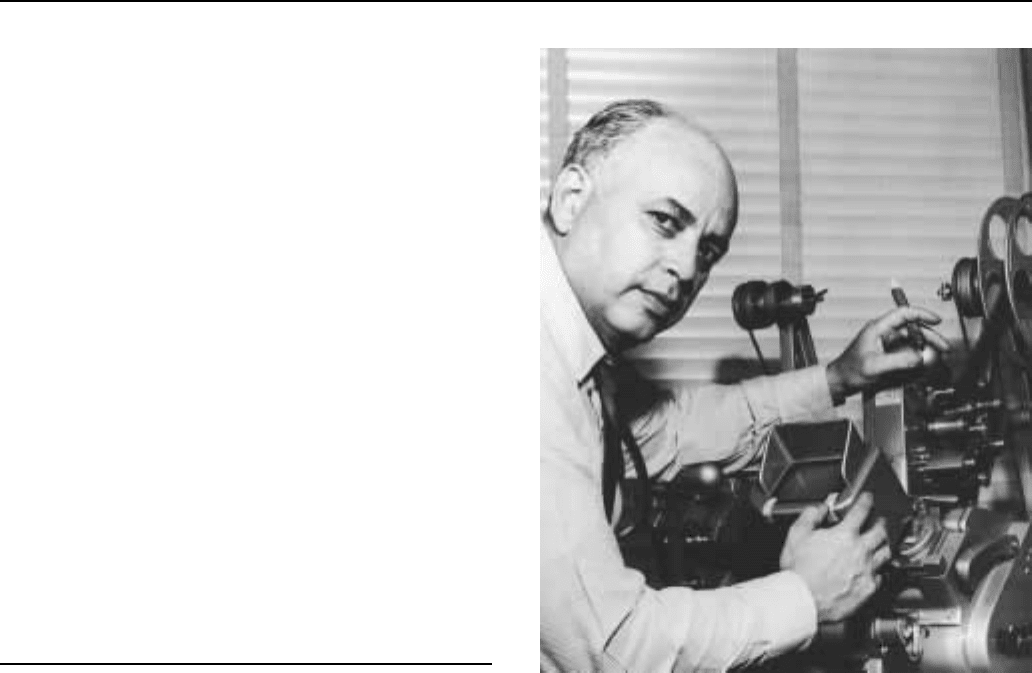

Funt was a former research assistant at Cornell University. His

prior broadcast experience included gag-writing for the radio version

of Truth or Consequences, serving as a consultant to Franklin D.

Roosevelt’s wife, Eleanor, for her radio broadcasts during her hus-

band’s presidency, and independent radio production for such pro-

grams as Ladies Be Seated. During the Second World War he served

in an Army Signal Corps unit in Oklahoma, where, using equipment

assigned to him for recording soldiers’ letters home, he began hidden-

microphone taping of gripes by his fellow servicemen for broadcast

on Armed Forces Radio. Funt’s Candid Microphone, a postwar

civilian version of the same idea, was first broadcast in 1947. A year

later, he took the show to television, and ABC carried it—still as

Candid Microphone—from August through December of 1948. The

program, now renamed Candid Camera, shuffled among the three

networks for the next five years, ending with NBC in the sum-

mer of 1953.

Allen Funt of Candid Camera.

After a seven year hiatus, Candid Camera was revived on CBS,

where it ran from October of 1960 through September of 1967. Co-

hosting the show in its first season was Arthur Godfrey, followed by

Durward Kirby for the next five years, and Bess Myerson (ironically

destined to become New York City’s consumer-affairs director) in

1966-1967. As its fame spread, Candid Camera was imitated even

overseas: in Italy, a program called Lo Specchio Segreto (‘‘I See It in

Secret’’), emceed by Nanni Loy, first aired in 1964 on the RAI

network; it too spawned numerous imitations. Funt, meanwhile,

returned to America’s airwaves with a syndicated version of the

program, The New Candid Camera, which was broadcast on various

networks from 1974 to 1978. Moviegoers were also exposed to

Candid Camera, both in Funt’s 1970 film What Do You Say to a

Naked Lady? and in a generous handful of 1980s home-video reprints

of episodes from the shows as well.

Some of Funt’s stunts have become classics in the manipulation

of frame and the reactions of the unsuspecting victims (almost always

punchlined by Funt or one of his accomplices saying ‘‘You’re on

Candid Camera.’’) In one sequence, a roadblock was stationed at a

border-crossing from Pennsylvania into Delaware to turn motorists

back with the explanation, ‘‘The state is full today.’’ Taste was a

timeless source of merriment: an airport water cooler was filled with

lemonade; and customers in a supermarket were asked to sample and

comment on a new candy bar made with ingredients in a combination

designed to be revolting.

The relationship between the television studio and the psycholo-

gy laboratory was not lost on Funt, who told readers of Psychology

Today that he had switched from sound recording to television

CANOVAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

421

because he ‘‘wanted to go beyond what people merely said, to record

what they did—their gestures, facial expressions, confusions and

delights.’’ By comparison with later (and sassier) imitators such as

America’s Funniest Home Videos and Totally Hidden Video, both of

which premiered in the late 1980s, Funt was scrupulous about

declining to air, and actually destroying, off-color or overly intrusive

footage. Candid Camera aspired to be humor but also art: ‘‘We used

the medium of TV well,’’ Funt would write proudly. ‘‘The audience

saw ordinary people like themselves and the reality of events as they

were unfolding. Each piece was brief, self-contained and the simple

humor of the situation could be quickly understood by virtually

anyone in our audience.’’

The New Candid Camera returned to television in the 1990s,

now touted as ‘‘the granddaddy of all ‘gotcha’ shows’’ and co-hosted

by Funt’s son Peter, who as a child had made his debut on the show

posing as a shoeshine boy charging $10 a shoe. Although the revival

was not renewed by King Productions for the 1992-1993 season,

specials continued to be made throughout the decade, mixing contem-

porary situations (a petition drive in Toronto advocating joint United

States-Canada holidays, a fake sales rep selling a fictitious and

overpriced line of business equipment to unsuspecting office manag-

ers) with classic sequences from the old shows. By this time Allen

Funt, now in his eighties, was living comfortably in retirement.

—Nick Humez

F

URTHER READING:

Dunning, John. Tune In Yesterday. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey,

Prentice Hall, 1976.

Funt, Allen. Eavesdropping at Large: Adventures in Human Nature

with Candid Mike and Candid Camera. New York, Vanguard

Press, 1952.

Loomis, Amy. ‘‘Candid Camera.’’ Museum of Broadcast Communi-

cations Encyclopedia of Television. Ed. Horace Newcomb. Chica-

go, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997, 305-307.

McNeil, Alex. Total Television. New York, Penguin Books, 1991.

West, Levon (writing as ‘‘Ivan Dmitri’’). How to Use Your Candid

Camera. New York, Studio Publications, 1932.

Zimbardo, P. ‘‘Laugh Where We Must, Be Candid Where We Can.’’

Psychology Today. June 1985, 42-47.

Caniff, Milton (1907-1988)

A popular and innovative adventure-strip artist, and one who

was much imitated, Milton Caniff began drawing newspaper features

in the early 1930s and kept at it for the rest of his life. He was born in

Hillsboro, Ohio, in 1907 and raised in Dayton. Interested in drawing

from childhood, in his early teens he got a job in the art department of

the local paper. By the time he was in college at Ohio State, Caniff

was working part-time for the Columbus Dispatch. It was there that he

met and became friends with Noel Sickles, the cartoonist-illustrator

who was to have such a profound effect on his approach to drawing.

Caniff created three continuity strips: Dickie Dare, Terry and the

Pirates, and Steve Canyon. From almost the beginning, his story lines

Milton Caniff

and dialogue were relatively sophisticated, influenced by the mov-

ies, as was his drawing style, which used cinematic shots and

impressionistic inking.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Goulart, Ron. The Funnies. Holbrook, Adams Publishing, 1995.

Harvey, Robert C. The Art of the Funnies. Jackson, University Press

of Mississippi, 1994.

Cannabis

See Marijuana

Canova, Judy (1916-1983)

Comedienne Judy Canova was one of the hidden gems Ameri-

can popular culture, ignored by critics and overlooked by ratings

systems that valued big city audiences yet beloved by audiences in

smaller markets. As a musical comedienne whose lifelong comic

persona was that of a yodeling country bumpkin, Judy Canova was

famous on stage, screen, and radio throughout the 1930s, 1940s and

1950s, but largely because of the perceived low status of her audience,

her popularity has often been overlooked.

CANSECO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

422

Judy Canova was born Juliette Canova on November 20, 1916,

in Starke, Florida. Her career in show business began while she was

still a teenager when she joined with her older brother and sister in a

musical trio which played the club circuit in New York. In addition to

belting out many of the same country songs she would perform for the

rest of her life, Canova also developed her comic persona during this

period as well—that of a good-natured, horse-faced, broadly grinning

hillbilly whose lack of education and etiquette was transcended by

boisterous good spirits, an apparent absence of pretense, and a naive

humor with which her audience could both identify and feel superior

to simultaneously. ‘‘I knew I would never be Clara Bow,’’ she later

recalled. ‘‘So I got smart and not only accepted my lack of glamour,

but made the most of it.’’ She usually wore her hair in pigtails, and

soon began wearing the checkered blouses and loosely falling white

socks which helped emphasize her almost cartoonlike appeal. The

comic portrait was soon completed with the development of a

repeated catchphrase (‘‘You’re telling I’’) and her use of what film

historian Leonard Maltin has referred to as ‘‘an earsplitting yodel.’’

With her character firmly in place by the early 1930s, it remained only

for Canova to find the appropriate outlet for its display.

Canova’s film career reached its high point in 1935 with her

brief appearance in the Busby Berkeley-directed In Caliente, in which

she performed what biographer James Robert Parish refers to as ‘‘her

most memorable screen moment.’’ In the middle of leading lady

Winifred Shaw’s serious performance of the soon-to-be popular

‘‘Lady in Red,’’ Canova appeared in hillbilly garb and belted out a

comic parody of the song in a performance singled out by audiences

and reviewers alike as the highlight of the movie. This success fueled

her stage career, leading to a notable appearance in the Ziegfeld

Follies of 1936, but Paramount’s attempt to make her a major film star

the following year (in Thrill of a Lifetime) didn’t pan out, and

Canova’s movie career was shifted to the lower budget projects of

Republic Studios. Here she starred in a series of consistently popular

musical comedies (Scatterbrain (1940), Sis Hopkins (1941), and Joan

of Ozark (1942) being among the most successful) in which she

played her well-established ‘‘brassy country bumpkin with a heart of

gold’’ in stories which enabled her to deliver a lot of bad puns and

yodel songs while demonstrating both the comic naiveté and moral

superiority of ‘‘the common people.’’ Behind the scenes, however,

Canova was anything but the untutored innocent she played onscreen,

and she is important as one of the first female stars to demand and

receive both a share of her film’s profits and, later, producing rights

through her own company.

While she was a minor star in the world of film, Canova was a

major success in radio. Earlier performances on the Edgar Bergen-

Charlie McCarthy Chase and Sanborn Hour (including a highly

publicized ‘‘feud’’ in which Canova claimed that the dummy had

broken up her ‘‘engagement’’ to Edgar) garnered such response that

The Judy Canova Show was all but inevitable. Even in her own time,

however, much of Canova’s popularity was ‘‘hidden’’ by conven-

tional standards, and it was not until 1945 when the new Hooper

ratings system (which measured the listening habits of small-town

and rural audiences for the first time) revealed that Canova’s program

was one of the top ten radio shows on the air. The Judy Canova Show

remained popular until its demise in 1953, a casualty of the declining

era of old-time radio. Radio allowed Judy to give full vent to the

characteristics which had endeared her to her audience, playing a

country bumpkin (with her own name) hailing from Unadella, Geor-

gia, but making constant visits to the big city to visit her rich aunt, and

passing a fastpaced series of corny jokes and songs with a series

of stock characters. A typical episode would be certain to have

Pedro the gardener (Mel Blanc) apologize to Judy ‘‘for talking in

your face, senorita,’’ Judy telling her aunt that she would be hap-

py to sing ‘‘Faust’’ at the aunt’s reception since she could sing

‘‘Faust or slow,’’ and close with Judy’s trademark farewell song,

‘‘Goodnight, Sweetheart.’’

After the end of her radio show, Canova continued her stage

career (including a primary role in 1971’s notable revival of the

musical No, No Nanette), made a few forays into early television, and

even attempted a more serious dramatic role in 1960’s The Adven-

tures of Hucklberry Finn. For the most part, however, she lived

comfortably in retirement, often accompanied by her actress daughter

Diana, product of her fourth marriage. The comic persona she created,

and the ethic it expressed, remain popular today in sources as diverse

as The Beverly Hillbillies and many of the characters played by the

hugely successful Adam Sandler, both of whom owe a large if

‘‘hidden’’ debt to a horsefaced yodeler with falling socks who never

let the city folk destroy her spirit.

—Kevin Lause

F

URTHER READING:

Maltin, Leonard, editor. Leonard Maltin’s Movie Encyclopedia. New

York, Dutton, 1996.

Parish, James Robert. The Slapstick Queens. New York, A.S. Barnes

and Company, 1973.

Parish, James Robert, and William T. Leonard. The Funsters. New

Rochelle, Arlington House, 1979.

Canseco, Jose (1964—)

Baseball’s Rookie of the Year in 1986, slugging outfielder Jose

Canseco helped the Oakland Athletics to World Series appearances

from 1988 to 1990, while becoming the first ballplayer ever to hit over

40 homers and steal 40 bases in a season (1988). Auspicious begin-

nings, teen-idol looks, and Canseco was suddenly the sport’s top

celebrity. As big money, 1-900 hotlines, and dates with Madonna

ensued, Canseco’s on-field and off-field behavior became erratic.

Headlines detailed a weapons arrest, reckless driving, and an acrimo-

nious public divorce. Traded away from Oakland in 1992, he blew out

his arm in a vanity pitching appearance and topped blooper reels when

a fly ball bounced off his head for a home run. Having dropped out of

both the limelight and the lineup, he eventually recovered to hit 46

homers for Toronto in 1998 (the same year his former Oakland ‘‘Bash

Brother’’ Mark McGwire hit a record 70).

—C. Kenyon Silvey

F

URTHER READING:

Aaseng, Nathan. Jose Canseco: Baseball’s 40-40 Man. Minneapolis,

Lerner Publications, 1989.

Scheinin, Richard. Field of Screams: The Dark Side of America’s

National Pastime. New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.

CANTORENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

423

Cantor, Eddie (1882-1964)

Dubbed ‘‘Banjo Eyes’’ for his expressive saucer-like orbs, and

‘‘The Apostle of Pep’’ for his frantically energized physical style,

comic song-and-dance man Eddie Cantor came from the vaudeville

tradition of the 1920s, and is remembered as a prime exponent of the

now discredited blackface minstrel tradition, his brief but historic

movie association with the uniquely gifted choreographic innovator

Busby Berkeley, and for turning the Walter MacDonald-Gus Kahn

song ‘‘Making Whoopee’’ into a massive hit and an enduring

standard. In a career that spanned almost 40 years, Cantor achieved

stardom on stage, screen, and, above all, radio, while on television he

was one of the rotating stars who helped launch the Colgate

Comedy Hour.

Cantor’s is a prototypical show business rags-to-riches story. As

Isadore Itzkowitz, born into poverty in a Manhattan ghetto district and

orphaned young, he was already supporting himself in his early teens

as a Coney Island singing waiter with a piano player named Jimmy

Durante before breaking into burlesque and vaudeville (where he

sang songs by his friend Irving Berlin), and made it to Broadway in

1916. The small, dapper Jewish lad became a Ziegfeld star, appearing

in the Follies of 1917 (with Will Rogers, W.C. Fields, and Fanny

Brice), 1918, and 1919. In the first, he sang a number in blackface,

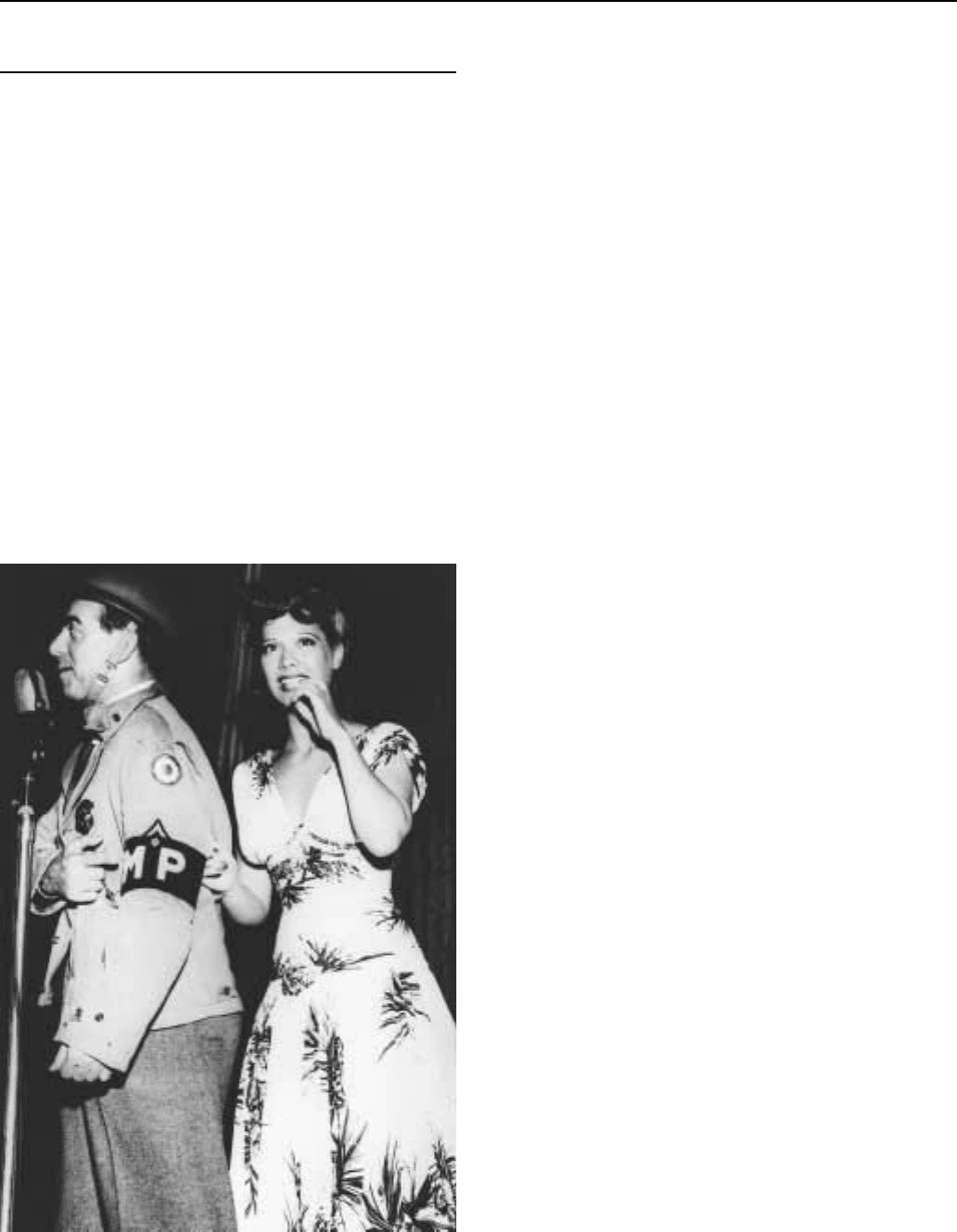

Eddie Cantor and Dinah Shore

and also applied the burnt cork to team in a skit with black comedian

Bert Williams, with whom he would work several times over the

years. Irving Berlin wrote the 1919 songs and Cantor introduced

‘‘You’d be Surprised.’’ A bouncy, hyperactive performer, he rarely

kept still and would skip and jump round the stage, clapping his

white-gloved hands while performing a song. He also rolled his

prominent eyes a lot and a Ziegfeld publicity hack came up with the

Banjo Eyes sobriquet.

After a falling out with Flo Ziegfeld, Cantor starred in other

people’s revues for a few years. Reconciled with Ziegfeld, he starred

in the musicals Kid Boots and Whoopee! The first became the silent

screen vehicle for his Hollywood debut in 1926; the second, based on

a play The Nervous Wreck, cast Cantor as a hypochondriac stranded

on a ranch out West, introduced the song ‘‘Making Whoopee,’’ and

brought him movie stardom when Samuel Goldwyn filmed it in 1930.

Whoopee! was not only one of the most successful early musicals to

employ two-tone Technicolor, but marked the film debut of Busby

Berkeley, who launched his kaleidoscopic patterns composed of

beautiful girls (Betty Grable was one) to create a new art form. The

winning formula of Berkeley’s flamboyance and Cantor’s insane

comedic theatrics combined in three more immensely profitable box-

office hits: Palmy Days (1931), which Cantor co-wrote; The Kid from

Spain (1932), in which Berkeley’s chorus included Grable and

Paulette Goddard; and, most famously, the lavish, and for its day

outrageous, Roman Scandals (1933), in which the young Lucille Ball

made a fleeting appearance. A dream fantasy, in which Cantor is

transported back to ancient Rome, the star nonetheless managed to

incorporate his blackface routine, while the ‘‘decadent’’ production

numbers utilized black chorines in a manner considered demeaning

by modern critics.

Meanwhile, the ever-shrewd Cantor was establishing himself on

radio ahead of most of his comedian colleagues. In 1931 he began

doing a show for Chase and Sanborn Coffee. By its second year,

according to radio historian John Dunning, it was the highest rated

show in the country. The star gathered a couple of eccentric comedi-

ans around him, beginning with Harry ‘‘Parkyakarkus’’ Einstein,

who impersonated a Greek, and Bert Gordon, who used a thick accent

to portray The Mad Russian, while, over the years, the show also

featured young singers such as Deanna Durbin, Bobby Breen, and

Dinah Shore. Cantor remained on the air in various formats until the

early 1950s, backed by such sponsors as Texaco, Camel cigarettes,

toothpaste and laxative manufacturers Bristol Myers, and Pabst Blue

Ribbon beer. His theme song, with which he closed each broadcast,

was a specially arranged version of ‘‘One Hour with You.’’

After his flurry of screen hits during the 1930s, Cantor’s movie

career waned somewhat, but he enjoyed success again with Show

Business (1944) and If You Knew Susie (1948), both of which he

produced. A cameo appearance in The Story of Will Rogers (1952)

marked the end of his 26-year, 16-film career, but in 1950 he had

begun working on television, alternating with comedians such as Bob

Hope, Martin and Lewis, and his old buddy Durante, as the star of

Colgate’s Comedy Hour. In the autumn of 1952 Cantor had a serious

heart attack right after a broadcast and left the air for several months.

He returned in 1953, but began gradually withdrawing from the

entertainment world.

Eddie Cantor wrote four autobiographical books, and in 1953,

Keefe Brasselle played the comedian in a monumentally unsuccessful

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

424

biopic, The Eddie Cantor Story. In 1956 the Academy honored him

with a special Oscar for ‘‘distinguished service to the film industry.’’

In 1962, the year he published the last of four autobiographical books,

he was predeceased by his wife, Ida, immortalized in the song, ‘‘Ida,

Sweet as Apple Cider,’’ to whom he was married for 48 years. Eddie

Cantor died two years later. His screen persona was not, and is not, to

everyone’s taste, and in life, some found him egocentric and difficult.

He remains, however, inimitable.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Barrios, Richard. A Song in the Dark. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1995.

Bordman, Gerald. American Musical Theatre. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1978.

Dunning, John. On The Air. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Goldman, Herbert G. Banjo Eyes: Eddie Cantor and the Birth of

Modern Stardom. New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Fisher, James. Eddie Cantor: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Con-

necticut, Greenwood Press, 1997.

Koseluk, Gregory. Eddie Cantor: A Life in Show Business. Jefferson,

North Carolina, McFarland, 1995.

Capital Punishment

Throughout the twentieth century, America remained one of the

few industrialized countries which carried out executions of crimi-

nals. Most trace this attitude to the Biblical roots of the country and

the dictum of ‘‘eye for an eye’’ justice. Those who wished to abolish

the death penalty saw the practice as bloodlust, a cruel and unusual

punishment anachronistic in modern times. In the late 1990s, the issue

remains a controversial one, with many states opting for the death

penalty. In response and with an ironic twist, America has searched

for ways to carry out executions as quickly and painlessly for the

condemned as possible.

At the turn of the twentieth century, America was trying to shake

a lingering sense of Old West vigilante justice. Thomas Edison,

among others, had campaigned for the relatively humane death

offered by electrocution. By the 1900s the electric chair had already

become the most popular form of execution, supplanting hanging. In

1924 Nevada instituted and performed the first gas chamber execu-

tion, which many believed again was the most humane method of

execution to date.

Spearheading the movement against the death penalty was

attorney Clarence Darrow, best known as defense counsel in the

Scopes Trial. Few were surprised when in 1924 Darrow, a champion

of lost causes, represented 18-year-old Richard Loeb and 19-year-old

Nathan Leopold, notorious friends and lovers who kidnapped and

murdered a 14-year-old boy. Darrow advised the two to plead guilty

in an attempt to avoid the death penalty. In what has been character-

ized as the most moving court summation in history, lasting over 12

hours, Darrow succeeded in convincing the judge to sentence the boys

to life in prison. Darrow commented, ‘‘If the state in which I live is not

kinder, more human, and more considerate than the mad act of these

two boys, I am sorry I have lived so long.’’ In spite of his eloquent

pleas, support for the death penalty remained high, with the highest

number of executions of the century occurring in the 1930s.

In one of the most notorious cases of the twentieth century, the

Italian immigrant workers Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti

were convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1920. Worldwide

response to their sentencing was overwhelming. The case against

them was not airtight—many believe later evidence suggested their

innocence. But their status as communists spelled their doom. Ac-

cording to the editors of Capital Punishment in the United States,

‘‘Many people believed that they were innocent victims of the

frenzied ‘Red Scare’ that followed World War I, making every

foreigner suspect—especially those who maintained unpopular po-

litical views.’’ Celebrities such as George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells,

Albert Einstein, and Sinclair Lewis protested the verdicts, to no avail

as the two were executed in the Massachusetts electric chair in 1927.

The so-called ‘‘Trial of the century,’’ the case of the kidnapping

and murder of the Lindbergh baby in 1935, also involved an immi-

grant: German-born defendant Bruno Hauptmann, convicted in 1935

and executed for the crimes in 1936. The trial defined the term

‘‘media circus,’’ with columnist Walter Winchell at the forefront

calling for swift punishment of Hauptmann. In spite of compelling

circumstantial evidence linking Hauptmann to the crime, his procla-

mation of his innocence to the end—even after being offered commu-

tation of his sentence in return for his confession—made many

uncomfortable because the case still seemed to lack closure.

Fear of communism ran at a fever pitch in the 1950s, contribut-

ing to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for treason in 1953.

Convicted of passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet

Union, the Rosenbergs were blamed by the trial judge for communist

aggression in Korea and the deaths of over 50,000 people. Polls at the

time showed enormous support for the death penalty in cases of

treason, largely due to the media notoriety of the Rosenberg case.

Still, a groundswell of reaction against the sentencing occurred,

forcing President Eisenhower himself to uphold the decision. While

the case against Julius Rosenberg was strong, the case against Ethel

was not, and many attribute her death as a casualty of the Cold War

communist scare.

After the Rosenbergs, the majority of executions in the United

States involved murderers. The Charles Starkweather case in the

1950s helped shape public perception of serial killers. After kidnap-

ping 14-year-old Caril Ann Fugate as a companion, Starkweather

went on a killing spree from Nebraska through Montana, murdering

11 people. When captured, Starkweather relished the media attention

as if he were a Hollywood star; he fancied himself a James Dean type,

heroically rebelling against society. Later, Bruce Springsteen’s song

‘‘Nebraska,’’ along with the 1973 movie Badlands, would immortal-

ize the Starkweather persona—both also helped form the basis of the

killers in the movies Wild at Heart, True Romance, and Natural

Born Killers.

No one, however, defined the image of the serial killer more

completely than Charles Manson. He also linked himself to the

popular media; his obsession with the Beatles’ White Album, in

particular the song ‘‘Helter Skelter,’’ became the impetus for the

CAPONEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

425

savage murders he orchestrated through his ‘‘family’’ of followers.

During his trial he alternately declared himself Christ and Satan, at

one point shaving his head and tattooing an ‘‘X’’ (later modified to a

swastika) between his eyes. Though Manson did not personally

commit murder, he was convicted in 1971 and sentenced to die. While

he waited on death row, the Supreme Court ruled in 1972 that the

death penalty was not applied equally and was therefore unconstitu-

tional. As a result, over 600 prisoners on death row, including

Manson, had their sentences commuted to life. In the years that

followed, Manson regularly came up for parole. Throughout the

1980s and 1990s, Manson resurfaced on television interview shows,

still seeming out of his mind. The specter of such a criminal possibly

being released always spurred a fresh outpouring of public outrage.

Very likely as a direct result of the Manson case, support for the death

penalty continued to rise, reaching a record high of 80 percent in 1994.

Once the states rewrote uniform death penalty laws that satisfied

the Supreme Court, executions resumed when Utah put Gary Gilmore

to death in 1977. A circus atmosphere surrounded this case, as both

supporters and opponents of the death penalty crowded outside the

prison. Gilmore’s face appeared on T-shirts as he too became a

national celebrity. Gilmore himself, however, actually welcomed the

death penalty; he refused all appeals and led the campaign for his right

to die. Later, Norman Mailer wrote a bestselling book entitled The

Executioner’s Song, which was subsequently made into a popular film.

When Ted Bundy was convicted as a serial killer in 1980, he put

a vastly different face on the image of murderer. Bundy was hand-

some and personable, traits which enabled him over two decades to

lure at least 30 women to their deaths. During his numerous appeals of

his death sentence Bundy claimed that consumption of pornography

had molded his behavior, warping his sense of sexual pleasure to

include violence against women. While his pleas helped raise debate

over the issues of pornography, they failed to save his life and Bundy

was executed in 1989.

The drifter Henry Lee Lucas, whose confessions to over 600

murders would make him the most prolific murderer of the century,

was sentenced to death in 1984. His exploits were fictionalized in the

cult movie Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1990). Later, however,

Lucas recanted all of his confessions and his sentence was commuted

to life in prison in 1998.

Television talk show host Phil Donahue, a death penalty oppo-

nent, campaigned vigorously in the 1980s to televise a live execution.

Some thought the idea merely a macabre publicity stunt while others

thought the public should be made to witness its sanctioned form of

punishment. Although Donahue was unsuccessful in his attempts, in

1995 the academy award winning movie Dead Man Walking inti-

mately depicted the last days of convicted murderer Patrick Sonnier.

The movie’s portrayal of the incident suggested that even death by

lethal injection—first used in Texas in 1982 in an effort to achieve a

more humane ending—was neither antiseptic nor instantaneous.

In 1997 the case of Karla Faye Tucker was brought to the

attention of the national media in an effort led by television evangelist

Pat Robertson. Tucker, a convicted double murderer, reportedly had

experienced a religious conversion while on death row. Based on this

and a profession of remorse for the crimes she committed, Robertson

argued for mercy. Tucker’s image captured the imagination of many

Americans: she was a young, attractive woman with a mild demeanor,

not at all the serial killer image America had come to expect from its

death-row inmates. While Tucker was not granted a new hearing and

was executed by lethal injection in 1998, her case influenced the

staunchest traditional supporters of the death penalty. For many

religious conservatives, the Tucker case reminded them that any

search for a truly humane punishment must eventually confront the

entire spectrum of emotions . . . not only revenge, but also the

qualities of mercy.

—Chris Haven

F

URTHER READING:

Currie, Elliott. Crime and Punishment in America. New York,

Holt, 1998.

Darrow, Clarence. Clarence Darrow on Capital Punishment. Chica-

go, Chicago Historical Bookworks, 1991.

Kronenwetter, Michael. Capital Punishment: A Reference Hand-

book. New York, ABC-Clio, 1993.

Lester, David. Serial Killers: The Insatiable Passion. Philadelphia,

Charles Press, 1995.

Prejean, Helen. Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the

Death Penalty in the United States. New York, Vintage, 1996.

Vila, Brian, and Cynthia Morris, editors. Capital Punishment in the

United States: A Documentary History. Westport, Greenwood

Press, 1997.

Capone, Al (1899-1947)

Perhaps the most recognizable figure in the history of organized

crime in the United States, Al Capone gained international notoriety

during the heady days of Prohibition when his gang dominated the

trade in bootleg alcohol in Chicago. Known as ‘‘Scarface’’ for the

disfiguring scars that marked the left side of his face, Capone

fascinated Chicago and the nation with his combination of street

brutality, stylish living, and ability to elude justice during the 1920s.

Even after his conviction on charges of tax evasion in 1931, Capone

remained a dominant figure in the national culture, with the story of

his rise and fall—which author Jay Robert Nash has succinctly

described as being from ‘‘rags to riches to jail’’—serving as the

archetype of gangster life in film and television portrayals of Ameri-

can organized crime.

Capone was born to Italian immigrant parents on January 17,

1899, in the teeming Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York.

By age eleven he had become involved with gang activities in the

neighborhood; he left school in the sixth grade following a violent

incident in which he assaulted a female teacher. Developing expert

street-fighting skills, Capone was welcomed into New York’s notori-

ous Five Points Gang, a vast organization that participated in burgla-

ry, prostitution, loan-sharking, and extortion, among its myriad

criminal activities. He came under the influence of Johnny Torrio, an

underboss who controlled gambling, prostitution, and influence ped-

dling in Williamsburg. Under Torrio, Capone worked as an enforcer

and later got a job as a bouncer and bartender at the gang-controlled

CAPOTE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

426

Al Capone (left)

Harvard Inn. During this time an altercation with a knife-wielding bar

patron resulted in the famous scars that came to symbolize Capone’s

violent persona. He was arrested for suspicion of murder in 1919 in

New York City, but the charges were dismissed when witnesses

refused to testify against him. He followed Torrio to Chicago later in

the same year after killing another man in a fight.

Posing as a used furniture dealer, Capone quickly became a

significant force in the underworld of Chicago, where the number of

corrupt law enforcement and government officials helped to create an

atmosphere of lawlessness. When the Volstead Act outlawed the

manufacture and distribution of liquor in 1920, Capone and Torrio

entered into a bootlegging partnership, and Capone assassinated the

reigning syndicate boss, ‘‘Big Jim’’ Colosimo, to clear the way for

their profiteering. The combined operations of prostitution and boot-

leg liquor were generating millions of dollars in profits in the mid-

1920s, but the Torrio-Capone organization repeatedly battled violent-

ly with rival gangs in the city, most notably with the operations

headed by Dion O’Bannion on Chicago’s north side. Following

O’Bannion’s murder in November 1924, Torrio was convicted of

bootlegging and several days later was wounded in a retaliatory attack

by O’Bannion’s men. He subsequently left the city, and Capone

gained full control of the multimillion dollar criminal activities in

gambling, prostitution, and liquor.

The late 1920s saw increasingly reckless violence in the streets

of Chicago among the warring criminal factions. Several attempts

were made on Capone’s life by his enemies, including an attempted

poisoning and a machine-gun attack on Capone’s headquarters in

suburban Cicero by the O’Bannions in 1926. In the most notorious

event of the period, which became known as the St. Valentine’s Day

Massacre, Capone hired a crew to kill rival Bugs Moran on February

14, 1929. Capone’s operatives, posing as police officers, executed all

seven men they found in Moran’s headquarters. Moran, however, was

not among the victims, and the public expressed outrage at the brutal

mass murder. By 1930 Capone had effectively eliminated his criminal

competitors, but he faced a new adversary in federal authorities.

When it was discovered that he had failed to pay income taxes for the

years 1924 to 1929, the Internal Revenue Service made its case, and

Capone was convicted of tax evasion in October 1931. He was

sentenced to eleven years in federal custody but was released because

of illness in 1939. He had developed paresis of the brain, a condition

brought on by syphilis, which he likely had contracted from a

prostitute during the 1920s. Suffering diminished mental capacity,

Capone lived the remainder of his life in seclusion at his Palm Island,

Florida, estate. He died in 1947.

—Laurie DiMauro

F

URTHER READING:

Dorigo, Joe. Mafia. Seacaucus, New Jersey, Chartwell Books, 1992.

Nash, Jay Robert. Encyclopedia of World Crime. Vol. I. Wilmette,

Illinois, CrimeBooks, 1990.

———. World Encyclopedia of Organized Crime. New York, De

Capo Press, 1993.

Sifakis, Carl. The Encyclopedia of American Crime. New York,

Smithmark, 1992.

Capote, Truman (1924-1984)

Truman Capote is one of the more fascinating figures on the

American literary landscape, being one of the country’s few writers to

cross the border between celebrity and literary acclaim. His wit and

media presence made for a colorful melange that evoked criticism and

praise within the same breath. For many, what drew them to him was,

for lack of a better word, his ‘‘attitude.’’ Capote relished deflating

fellow writers in public fora. In a televised appearance with Norman

Mailer, he said of Jack Kerouac’s work, ‘‘That’s not writing. That’s

typewriting.’’ In his unpublished exposé, Answered Prayers, his

description of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir at the Pony

Royal Bar in Paris could hardly have been less flattering: ‘‘Walleyed,

pipe-sucking, pasty-hued Sartre and his spinsterish moll, de Beauvoir,

were usually propped in a corner like an abandoned pair of ventrilo-

quist’s dolls.’’ And when wit had been set aside, he could be just

downright abusive, as when he described Robert Frost as an ‘‘evil,

selfish bastard, an egomaniacal, double-crossing sadist.’’ Capote’s

place in the twentieth century American literary landscape, however,

is clear. He contributed both to fiction and nonfiction literary genres

and redefined what it meant to join the otherwise separate realms of

reporting and literature.

The streak of sadism that characterized Capote’s wit stemmed

largely from his troubled childhood. Capote was born Truman Streckfus

CAPOTEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

427

Truman Capote

Persons on September 30, 1924 in New Orleans, the son of Archuylus

(Archie) Persons and Lillie May Persons Capote. At the age of four,

his parents divorced, and Truman became the itinerant ward of

various relatives in Alabama, several of whom would serve as

inspiration for his fictional creations in such works as his classic short

tale ‘‘A Christmas Memory’’ and first novel, Other Voices, Other

Rooms. When he was ten years old, he won a children’s writing

contest sponsored by the Mobile Press Register with his submission

of ‘‘Old Mr. Busybody.’’ Apropos of his later claim to fame as

literary gossip par excellence, the story itself, according to Capote,

was based on a local scandal that ended his brief writing career in

Monroeville, Alabama, for the next half-decade. At age 15, Capote

rejoined his mother and her second husband, Joseph Capote, in New

York, where he attended several local boarding schools. At age 17,

Capote decided to leave school for good, taking work as a copyboy at

The New Yorker.

From The New Yorker, Capote soaked up much of the literary

atmosphere. He also spent his leisure hours reading in the New York

Society Library, where, he claimed, he met one of his literary

heroines, Willa Cather. Capote’s career at The New Yorker ended

after two years when he supposedly fell asleep during a reading by

Robert Frost, who promptly showed his ire by throwing what he was

reading at the young reporter’s head. A letter to Harold Ross from the

fiery Frost resulted in Capote’s dismissal, and with that change in

circumstances, Capote returned to Alabama to labor three years over

his first major work, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948). Between

1943-46, as Capote worked on his novel, a steady stream of short

stories flowed from his pen, such as ‘‘Miriam,’’ ‘‘The Walls Are

Cold,’’ ‘‘A Mink of One’s Own,’’ ‘‘My Side of the Matter,’’

‘‘Preacher’s Legend,’’ and ‘‘Shut a Final Door.’’ The response to the

Other Voices, Other Rooms was immediate and intense. The lush

writing and homosexual theme came in for much criticism, while the

famous publicity shot of Capote supine on a couch, languidly staring

into the camera’s eye invited an equal mix of commentary and scorn.

Capote was only 23 years of age when he became a literary star

to be lionized and chastened by the critical establishment. Hurt and

surprised by the novel’s reception, although pleased by its sales,

Capote left to tour Haiti and France. While traveling, Capote served as

a critic and correspondent for various publications, even as he

continued to publish annually over the next three years Tree of Night

and Other Stories (1949), Local Color (1950), and The Grass Harp

(1951). By 1952, Capote had decided to try his hand at writing for

stage and screen. In 1952, Capote rewrote The Grass Harp for

Broadway and later in 1954 a musical called House of Flowers.

During this period, he also wrote the screenplay Beat the Devil for

John Huston. None fared particularly well, and Capote decided to

avoid theater and movie houses by resuming his activities as a

correspondent for The New Yorker. Joining a traveling performance

of Porgy and Bess through the Soviet Union, he produced a series of

articles that formed the basis for his first book-length work of

nonfiction, The Muses Are Heard.

Capote continued to write nonfiction, sporadically veering aside

to write such classics as Breakfast at Tiffany’s and his famous short

tale, ‘‘A Christmas Memory.’’ The former actually surprised Capote

by the unanimously positive reception it received from the literary

establishment (including such curmudgeonly contemporaries as Nor-

man Mailer). In late 1959, however, Capote stumbled across the story

that would become the basis for his most famous work, In Cold Blood.

Despite the remarkable difference in content, The Muses Are Heard

trained Capote for this difficult and trying work that helped establish

‘‘The New Journalism,’’ a school of writing that used the literary

devices of fiction to tell a story of fact. The murder of the Clutter

family in Kansas by Perry Smith and Dick Hickok was to consume

Capote’s life for the next six years. Although many quarreled with

Capote’s self-aggrandizing claim that he had invented a new genre

that merged literature with reportage, none denied the power and

quality of what he had written. Whatever failures Capote may have

experienced in the past were more than made up for by the commer-

cial and critical success of In Cold Blood.

Capote would never write a work as great as In Cold Blood, and

with good reason, for the six years of research had taken a terrible toll.

He did, however, continue to write short stories, novellas, interviews,

and autobiographical anecdotes, all of which were collected in such

works as A Christmas Memory, The Thanksgiving Visitor, House of

Flowers, The Dog’s Bark, and Music for Chameleons. On August 25,

1984, Truman Capote died before completing his next supposedly

major work, Answered Prayers, a series of profiles so devastating to

their subjects that Capote underwent a rather humiliating ostracism

from the social circles in which he had so radiantly moved. Still, no

one disputes Capote’s contribution to literature as a writer who taught

reporters how to rethink what they do when they ostensibly record

‘‘just the facts.’’

—Bennett Lovett-Graff

F

URTHER READING:

Clarke, Gerald. Capote. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1988.

Garson, Helen S. Truman Capote: A Study of the Short Fiction.

Boston, Twayne, 1992.

Grobel, Lawrence. Conversations with Capote. New York, New

American Library, 1985.

CAPRA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

428

Plimpton, George. Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Ene-

mies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Ca-

reer. Garden City, New Jersey, Doubleday, 1997.

Capp, Al

See Li’l Abner

Capra, Frank (1897-1991)

Although he is one of the most successful and popular directors

of all time, Frank Capra is seldom mentioned as one of Hollywood’s

great film auteurs. During his peak, as well as in the years that

followed, critics referred to his work as simplistic or overly idealistic,

and labeled his unique handling of complex social issues as ‘‘Capri-

corn.’’ The public on the other hand loved his films and came back

again and again to witness a triumph of the individual (predicated on

the inherent qualities of kindness and caring for others) over corrupt

leaders who were dominating an ambivalent society.

The Italian-born Capra moved to the United States at age six,

where he lived the ‘‘American Dream’’ he would later romanticize in

his films. Living in Los Angeles and working to support himself

through school, he sold newspapers, and worked as a janitor before

graduating with a degree in Chemical Engineering from Caltech (then

called Throop Polytechnic Institute) in 1918. After serving in the

military Capra stumbled onto an opportunity in San Francisco when

he talked his way into directing the one-reel drama Ballad of Fultah

Fisher’s Boarding House in 1922. The experience was significant in

that it convinced the young engineer to move back to Los Angeles and

pursue a film, rather than an engineering, career. Upon returning to

Los Angeles, Capra began the process of learning the film business

from the ground up. Starting as a propman and later becoming a ‘‘gag

writer,’’ Capra worked with directors Hal Roach and Mack Sennett

before hooking up as a director with silent comedian Harry Langdon.

Capra directed parts of three films produced during the peak of

Langdon’s career, including The Strong Man (1926), before the two

went their separate ways. Langdon is rumored to have tarnished the

young Capra’s name, which, despite his success, made it impossible

for him to find work in Hollywood. Unwilling to give up, Capra went

to New York for an opportunity to make a film with a new actress,

Claudette Colbert, titled For The Love of Mike (1927). Although the

film was Capra’s first flop, he signed a contract with studio head

Harry Cohn and began his relationship with Columbia Pictures. Capra

remained at Columbia for 11 years, and during this time he made at

least 25 films. All but two of them made money for the studio and

Capra is credited by many as being the key to Columbia’s rise to the

status of ‘‘major’’ Hollywood studio.

During his early years with Columbia some of Capra’s most

memorable works were the ‘‘service films’’ including: Submarine

(1928), Flight (1929), and Dirigible (1931). While producing profit-

able films at a fast pace for the studio, Capra decided in 1931 that he

wanted to tackle tougher social issues. While the country was in the

throes of the Depression, Capra hooked up with writer/collaborator

Robert Riskin, with whom he worked off and on for almost 20 years.

Together, Capra and Riskin produced a string of five Oscar-nominat-

ed films between 1933 and 1938. Included in this group were: Lady

for a Day (1933, nominated for Best Picture and Best Director); It

Happened One Night (1934, winner Best Director); Mr. Deeds Goes

to Town (1936, nominated Best Picture, winner Best Director); Lost

Horizon (1937, nominated Best Picture); and You Can’t Take it With

You (1938, winner Best Picture and Best Director). Although Capra

continued to collaborate with Riskin on two of his most memorable

works, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, (1939) and It’s a Wonderful

Life (1946) were penned in collaboration with others. It is, of course,

impossible to gauge how much credit Riskin deserves for Capra’s

meteoric rise in Hollywood. Some observers have suggested that even

though Riskin wasn’t involved in films like Mr. Smith Goes To

Washington, the form and structure clearly follow the pattern the two

successfully developed during their years of collaboration. Others,

like Capra himself, would point to the successful films without Riskin

as proof that the common denominator was the individual who

insisted his name come before the title of the film. Capra even called

his autobiography The Name Above the Title, and claims that he was

the first to be granted this status. Whether or not Capra’s claim has

validity, there is no doubt that people all over the country flocked to

the theaters during the 1930s and 1940s to see films directed by

Frank Capra.

Capra’s films regularly engaged political and social issues, and

in his professional life he was equally active. Capra served as the

President of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences

during a crucial period of its development. During his tenure Capra

oversaw a strengthening of the Academy and their annual Oscar

banquet. In 1936 he worked with the Screenwriters Guild to avoid a

boycott of the awards banquet, and in 1939 while serving as head of

the Directors Guild, Capra resigned his post with the Academy to lead

a director’s boycott of the Oscars which was instrumental in gaining

key concessions from the Academy. Never afraid to tackle tough

political issues in his films, Capra was no stranger to controversy or

difficult decisions in his professional career either.

While most of us today know Capra best from the perennial

holiday favorite It’s A Wonderful Life, the Capra myth is most solidly

grounded in Mr. Smith Goes To Washington. After the film was

previewed in Washington, D.C., it is rumored that Columbia was

offered $2 million (twice the cost of the film) not to release the film.

The alleged leader of this movement to shelve the film was Joseph P.

Kennedy, who was then Ambassador to Great Britain. Kennedy was

not alone in his concern over the film’s impact. In response to Mr.

Smith Goes To Washington, Pat Harrison, the respected publisher of

the Harrison Reports, asked exhibitors to appeal to Congress for the

right to refuse films that were ‘‘not in the interests of our country.’’

Ironically, this film was perhaps Capra’s most patriotic moment—

presenting the individual working within the democratic system to

overcome rampant political corruption. Needless to say, Capra and

Columbia refused to have the film shelved. The status of Mr. Smith

Goes to Washington was further established several years later when

the French were asked what films they wanted to see prior to the

occupation, and the overwhelming choice was none other than

Capra’s testimony for the perseverance of democracy and the Ameri-

can way, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington.

Following Mr. Smith, Capra demonstrated his patriotic duty by

enlisting in the United States Signal Corps during World War II.