Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CAPTAIN AMERICAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

429

Although he had served in the military before, and was old enough to

sit this one out, Capra had an intense desire to prove his patriotism to

his adopted land. While a member of the Armed Forces, Capra

oversaw the production of 11 documentaries under the series title Why

We Fight. The series was originally intended to indoctrinate Ameri-

can troops and explain why it was necessary for them to fight the

Second World War. When the first documentaries were completed

Army and government officials found them so powerful that they felt

the films should also be released to theaters so that everyone in

America could see them. Considered by many to be some of the best

propaganda films ever made, the Why We Fight series is still broad-

cast and used as a teaching tool today.

Following the war, Capra found success with It’s A Wonderful

Life and State of the Union, but he increasingly came to feel out of step

with a changing film industry. While his themes had struck a chord

with the Depression era society, his films seemed saccharin and out of

touch in prospering post-war America. Moving to Paramount in 1950,

Capra claimed that he became so disillusioned with the studio that he

quit making films by 1952. In his autobiography he blames his

retirement on the rising power of film stars (compromising the ability

to realize his artistic vision), and the increasing budgetary and

scheduling demands that studios placed upon him. Joseph McBride,

in The Catastrophe of Success, however, points out that Capra’s

disillusionment coincided with the questions and difficulties sur-

rounding the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC)

communist witch-hunt, which ended many Hollywood careers.

During a regrettable period of postwar hysteria Capra, de-

spite his military service and decorations, was a prime-target for

Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red-baiting committee. Although Capra

was never called to testify, his past associations with blacklisted

screenwriters such as Sydney Buchman, Albert Hackett, Ian McLelan

Hunter, Calrton Moss, and Dalton Trumbo (to name a few) led to his

being ‘‘greylisted’’ (but employable). Determined to demonstrate his

loyalty he attempted to rejoin the military for the Korean War, but was

refused. When invited as a civilian to participate in the Defense

Department’s Think Tank project, VISTA, he jumped at the opportu-

nity, but was later denied necessary clearance. These two rejections

were devastating to the man who had made a career of demonstrating

American ideals in film. Capra later learned that his application to the

VISTA was denied because he was part of a picket-line in the 1930s,

sponsored Russian War Relief, was active in the National Federation

for Constitutional Liberties (which defended communists), contribut-

ed to the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee in the 1940s, and had

a number of associates who were linked to the Communist Party.

Significantly, Capra made few films once the blacklisting began,

and none of them approached his previous critical and box office

success. By 1952, at the age of 55, Capra effectively retired from

feature filmmaking to work with Caltech and produce educational

programs on science. Once one of the most popular and powerful

storytellers in the world, Capra’s disenchantment with the business

and political climate of filmmaking left him disconnected from a

culture that was rapidly changing. Although he did make two more

major motion pictures A Hole in the Head (1959) and Pocketful of

Miracles (1961), Capra would never again return to the perch he

occupied so long atop the filmmaking world. In 1971 he penned his

autobiography The Name Above the Title, which served to revive

interest in his work and cement his idea of ‘‘one man, one film.’’ And

since his death in 1991, Frank Capra has been honored as one of the

seminal figures in the American century of the cinema.

—James Friedman

F

URTHER READING:

American Film Institute. Frank Capra: Study Guide. Washington

D.C., The Institute, 1979.

Capra, Frank. The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. New

York, Macmillan 1971.

Carney, Raymond. American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra.

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Maland, Charles J. Frank Capra. New York, Twayne Publish-

ers, 1995.

McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. New

York, Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Sklar, Robert and Vito Zagarrio, editors. Frank Capra: Authorship

and the Studio System. Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1998.

Captain America

Captain America is one of the oldest and most recognizable

superhero characters in American comic books. A flagship property

of Marvel Comics, Captain America has entertained generations of

young people since the 1940s. Perhaps no other costumed hero has

stood as a bolder symbol of patriotic American ideals and values.

Indeed, the history of Captain America can not be understood without

attention to the history of America itself.

Captain America sprang forth from the political culture of World

War II. In early 1941, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created the character

for Marvel Comics, which was struggling to increase its share of the

comic-book market. As early as 1939, comic books had periodically

featured stories that drew attention to the menace of Nazi Germany.

Simon and Kirby, who were both Jewish, felt very strongly about

what was happening in Europe under the Nazis and were emboldened

to defy the still powerful mood of isolationism in America. Captain

America would make the not-very-subtle case for American interven-

tion against the Axis powers.

The cover of the first issue of Captain America Comics por-

trayed the superhero in his red-white-and-blue costume, punching

Adolf Hitler in the mouth. That brash image set the aggressive tone

for the entire series. In the first issue, readers were introduced to Steve

Rogers, a fiercely patriotic young American. Physically inadequate

for military service, Rogers volunteers for a secret government

experiment to create an army of super soldiers. After drinking a serum

developed by Dr. Reinstein, Rogers is transformed into a physically

perfect human fighting machine. Immediately thereafter, a Nazi spy

assassinates Dr. Reinstein, whose secret formula dies with him, thus

insuring that Rogers will be the only super soldier. Donning a mask

and costume derived from the American flag and wielding a striped

shield, Rogers adopts the identity of Captain America and pledges to

wage war against the enemies of liberty at home and abroad.

CAPTAIN KANGAROO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

430

Assisted by his teenage sidekick Bucky, Captain America spent

the war years safeguarding American interests against conniving

German and Japanese agents. Simon and Kirby dreamed up some of

the most delightfully grotesque Axis caricatures to pit against the

heroes. Foremost among these was the Red Skull, a sinister Nazi

mastermind who became Captain America’s perennial archenemy.

Jack Kirby’s artwork for the series was among the most exuberant,

energetic, and imaginative in the field and helped to establish him as

one of the most influential superhero comic-book artists.

Captain America quickly became Marvel’s most popular attrac-

tion and one of the most successful superheroes of the World War II

years. Despite some early hate mail from isolationists who did not

appreciate the Captain America’s politics, the character found an avid

readership among young people receptive to the simple and aggres-

sive Americanism that he embodied. More than any other superhero,

Captain America epitomized the comic-book industry’s unrestrained

assault on the hated ‘‘Japanazis.’’ Indeed, the star-spangled superhero

owed so much to the wartime popular culture that he seemed to drift

when the war ended. During the postwar years, Captain America’s

sales declined along with those of most other costumed superheroes.

Even the replacement of Bucky with a shapely blond heroine named

Golden Girl failed to rejuvenate interest in the title. In 1949 Marvel

cancelled Captain America.

Marvel revived the hero in 1954 and recast him for the Cold War

era. Now billed as ‘‘Captain America—Commie Smasher,’’ the hero

embarked on a crusade to purge America of Reds and traitors.

Reentering the glutted comic-book market at a time when horror

comics predominated and McCarthyism was going into decline, it

was little wonder that this second incarnation of Captain America

became a short-lived failure.

The Captain’s third resurrection proved far more successful. In

1964, at the height of Marvel’s superhero renaissance, Stan Lee and

Jack Kirby revived the hero in issue number four of The Avengers.

The story explained that Captain America’s absence over the years

was due to the hero having literally been frozen in suspended

animation since the end of World War II. In keeping with Marvel’s

formula of neurotic superheroes, the revived Captain America strug-

gled with an identity crisis: Was he simply a naive relic of a nostalgic

past? Could he remain relevant in an era when unquestioning patriot-

ism was challenged by the turmoil of the Civil Rights movement, the

Vietnam War, and youth revolts?

By the early 1970s, Captain America symbolized an America

confused over the meaning of patriotism and disillusioned with the

national mission. The hero himself confessed that ‘‘in a world rife

with injustice, greed, and endless war . . . who’s to say the rebels are

wrong? I’ve spent a lifetime defending the flag and the law. Perhaps I

should have battled less and questioned more.’’ Accordingly, Captain

America loosened his longtime affiliation with the U.S. government

and devoted himself to tackling domestic ills like poverty, pollution,

and social injustice. He even took on a new partner called the Falcon,

one of the first African-American superheroes.

In a memorable multi-part series unfolding during the Watergate

scandal, Captain America uncovered a conspiracy of high-ranking

U.S. officials to establish a right-wing dictatorship from the White

House. This story line, written by a young Vietnam veteran named

Steve Englehart, left Captain America deeply disillusioned about

American political leadership—so much so that for a time he actually

discarded his stars and stripes in favor of a new costume and identity

of ‘‘Nomad—the Man Without a Country.’’ But Captain America re-

turned shortly thereafter, having concluded that even in this new age

of cynicism, the spirit of America was still alive and worth defending.

Captain America has remained a popular superhero in the last

decades of the twentieth century. The character may never be as

popular as he was during World War II, but as long as creators can

continue to keep him relevant for future generations, Captain Ameri-

ca’s survival seems assured. Although his patriotic idealism stands in

stark contrast to the prevailing trend of cynical outsider superheroes

like the X-Men, the Punisher, and Spawn, Captain America’s contin-

ued success in the comic-book market attests to the timelessness and

adaptability of the American dream.

—Bradford Wright

F

URTHER READING:

Captain America: The Classic Years. New York, Marvel Com-

ics, 1998.

Daniels, Les. Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Great-

est Comics. New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1991.

Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. The Comic Book Makers. New York,

Crestwood/II Publications, 1990.

Captain Kangaroo

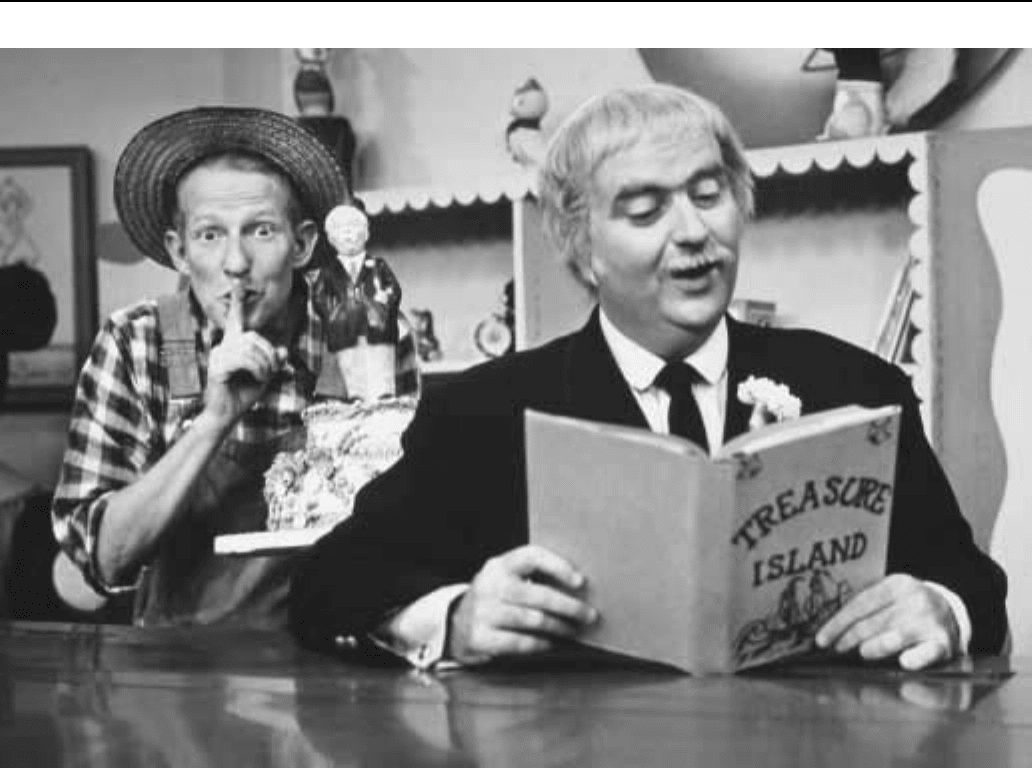

For those who were either children or parents from 1955 through

1991, the perky theme music of Captain Kangaroo, accompanied by

the jingling of the Captain’s keys as he unlocked the door to the

Treasure House, arouses immediate feelings of nostalgia. The longest

running children’s television show in history, Captain Kangaroo

dominated the early morning airwaves for over 30 years, offering a

simple and gently educational format for very young children.

The central focus of the show was always the Captain himself, a

plump, teddy bear-like figure with Buster Brown bangs and a mus-

tache to match. Much like another children’s television icon, Mister

Rogers, the Captain welcomed children to the show with a soft-voiced

sweetness that was never condescending, and guided viewers from

segment to segment chatting with the other inhabitants of the Treasure

House. Bob Keeshan created the comforting role of Captain Kanga-

roo, so named because of his voluminous pockets. His friends on the

show included a lanky farmer, Mr. Greenjeans, played by Hugh

Brannum, and Bunny Rabbit and Mr. Moose, animated by puppeteer

Gus Allegretti. Zoologist Ruth Mannecke was also a regular, bringing

unusual animals to show the young audience.

Captain Kangaroo also had regular animated features such as

‘‘Tom Terrific and His Mighty Dog Manfred.’’ One of the most

popular segments was ‘‘Story Time,’’ where the Captain read a book

out loud while the camera simply showed the book’s illustrations. It is

‘‘Story Time’’ that perhaps best illustrates Bob Keeshan’s unassum-

ing approach to children’s entertainment, operating on the theory that

children need kind and patient attention from adults more than

attention-grabbing special effects.

CAPTAIN KANGAROOENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

431

A typical moment from the Captain Kangaroo show.

Keeshan got his start in the world of television early, working as

a page at NBC when he was a teenager in Queens, New York. He left

New York to perform his military service in the Marines, then

returned to NBC where he got a job with the newly-popular Howdy

Doody Show. He created and played the role of Clarabell the Clown

on that show and was so successful that in 1955 CBS offered to give

him his own show. Keeshan created Captain Kangaroo, and the show

ran for 30 years on CBS. In 1984, it moved to PBS (Public Broadcast-

ing System), where it continued to run for another six years.

A father of three, and later a grandfather, Keeshan had always

been a supporter of positive, educational entertainment for children.

Even after leaving the role of the Captain, he continued to be an

advocate for children: as an activist, fighting for quality children’s

programming; as a performer, planning a cable television show about

grandparenting; and as a writer, producing gently moralistic child-

ren’s books as well as lists for parents of worthwhile books to read

to children.

The soft-spoken Keeshan was so identified with the role of

Captain Kangaroo that he was horrified when, in 1997, Saban

Entertainment— producers of such violence- and special effects-

laden shows as Power Rangers and X-Men—began to search for a

new, hip Captain to take the helm of The All-New Captain Kangaroo.

Saban had offered the role to Keeshan, but withdrew the offer when

he insisted on too much creative control over the show. Keeshan did

not want modern special effects and merchandising to interfere with

the Captain’s gentle message. ‘‘I really think they believe that kids are

different today than they were in the 1960s or 1970s,’’ he said.

‘‘That’s nonsense. They’re still the same, still asking the same

questions, ‘Who am I? Am I loved? What does the future hold for

me?’’’ In the end, however, Saban chose to stay with the proven

formula by choosing John McDonough to play the new Captain.

Neither hip nor slick, McDonough is a middle-aged, soft-spoken

lover of children, not so different from Keeshan’s Captain.

In an ironic twist, in 1995, the Motion Picture Association of

America, trying to forestall legislation against violence in children’s

programming, insisted that violence in programming does not lead to

violent activity. In fact, they suggested that the opposite might be true

and that perhaps Captain Kangaroo and other mild programming of

the 1950s led directly to the unrest of the 1960s and 1970s. Though

Keeshan scoffed at the implication, the tactic seems to have worked

and the legislation was defeated.

The media now abounds with choices of children’s program-

ming. With dozens of cable channels, children’s shows can be found

somewhere on television almost 24 hours a day. If that fails, parents

can buy videos to pop in whenever some juvenile distraction is

needed. In 1955, when the Captain debuted, and for many years

CAPTAIN MARVEL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

432

afterwards, there were only three television channels that broadcast

from around six a.m. until midnight. For children seeking entertain-

ment, for parents seeking amusement for their children, even for

adults seeking something to wile away the early morning hours, there

was only Captain Kangaroo. For these people, the Captain was like

an old friend, quietly accepting and unchanged over 30 years on the air.

In the 1960s, country music performers The Statler Brothers had

a hit song, ‘‘Countin’ Flowers on the Wall,’’ where a young man

describes his bleak and sleepless nights after being left by his girl.

Perhaps no one born after the video-and-cable era will be able to

completely grasp the desolate joke in the lines, ‘‘Playin’ solitaire ’til

dawn / With a deck of fifty-one / Smokin’ cigarettes and watchin’ /

Captain Kangaroo / Now, don’t tell me / I’ve nothing to do.’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Bergman, Carl, and Robert Keeshan. Captain Kangaroo: America’s

Gentlest Hero. New York, Doubleday, 1989.

Keeshan, Robert. Good Morning Captain: Fifty Wonderful Years

With Bob Keeshan, TV’s Captain Kangaroo. Minneapolis, Fairview

Press, 1996.

Raney, Mardell. ‘‘Captain Kangaroo for Children’s TV.’’ Education-

al Digest. Vol. 62, No. 9, May 1997, 4.

Captain Marvel

Captain Marvel was among the most popular comic-book

superheroes of the 1940s. Created in 1940 by Bill Parker and C.C.

Beck for Fawcett Publications, Captain Marvel was an ingeniously

simple premise. When teenager Billy Batson speaks the magic word

‘‘Shazam,’’ he transforms into a muscular adult superhero. Like DC

Comics’ Superman, Captain Marvel possessed superhuman strength,

invulnerability, and the power of flight.

Captain Marvel enlisted along with most other comic-book

superheroes into World War II and did his part to disseminate

patriotic propaganda about the virtues of America’s war effort. He

was the top-selling comic-book character of the war years—even out-

performing Superman for a time. By 1954, however, falling sales and

a long-standing lawsuit by DC over the character’s alleged similari-

ties to Superman forced Captain Marvel into cancellation. DC later

purchased the rights to the character and has published comic books

featuring him since the 1970s.

—Bradford Wright

F

URTHER READING:

Benton, Mike. Superhero Comics of the Golden Age. Dallas, Taylor

Publishing, 1992.

O’Neil, Dennis. Secret Origins of the Super DC Heroes. New York,

Warner, 1976.

Captain and the Kids, The

See Katzenjammer Kids, The

Car 54, Where Are You?

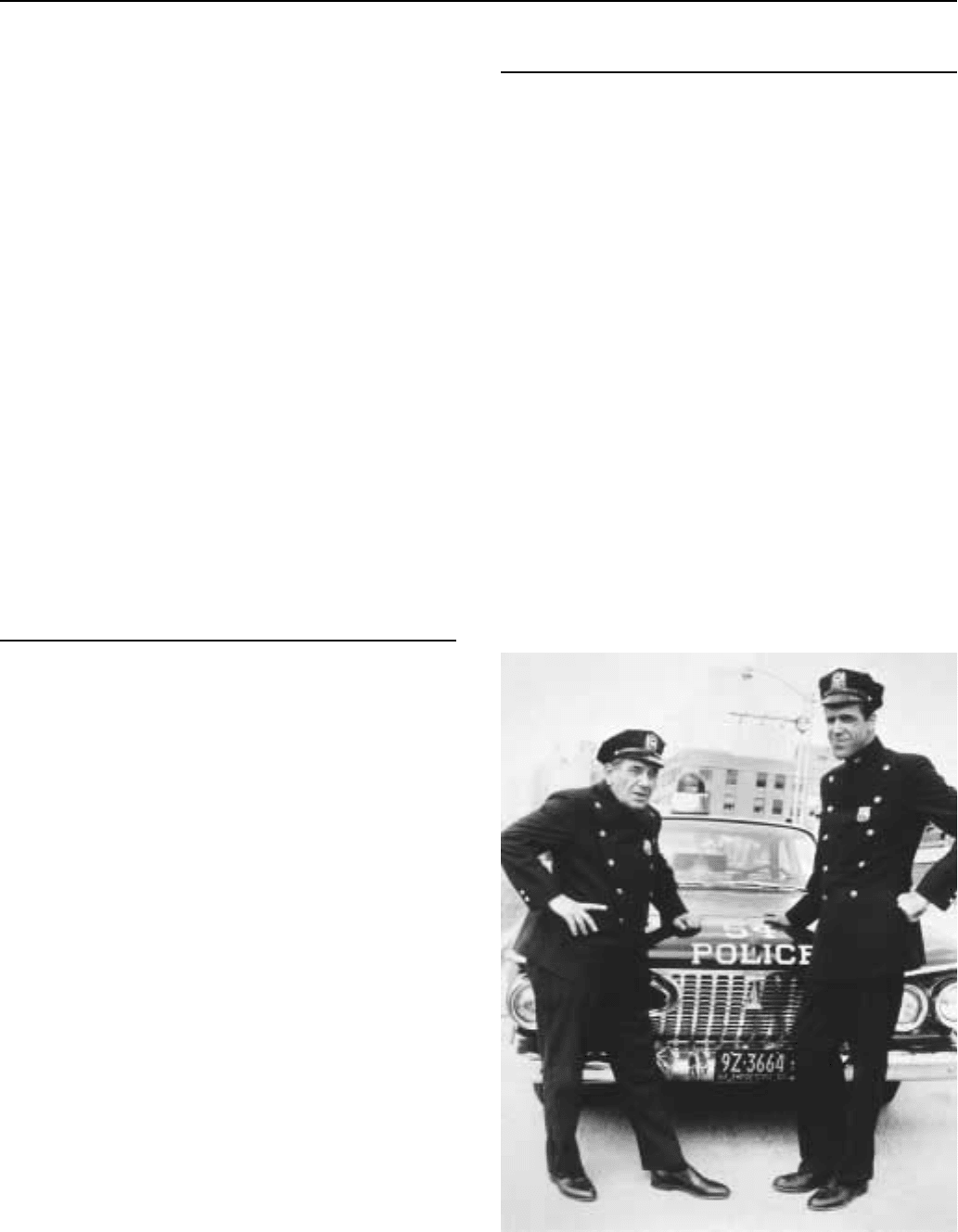

The situation comedy Car 54, Where Are You?, which ran on

NBC from 1961 to 1963, occupies a unique place in television history.

While it is a truly humorous look at the shenanigans of the police

officers assigned to the fictional 53rd precinct in the Bronx, it is most

often remembered as a minor cult classic filled with performers better

known from other series and for its catchy opening theme song. The

show focused on patrol-car partners Gunther Toody (Joe E. Ross) and

Francis Muldoon (Fred Gwynne) as they attempted to serve and

protect the citizens of New York. A more unlikely pairing of police

officers had never been seen on television. Toody was a short and

stocky, often slow-witted, talkative cop, and Muldoon was a tall and

gangly, usually laconic, intellectual. Episodes were filled with the

usual sitcom fare as the partners’ bumbling caused misunderstandings

within their squad, such as the time Toody attempted to make a plaster

cast of a fellow patrolman’s aching feet and chaos ensued. Each week

the pair caused their superior, Captain Block, to become infuriated as

they made more trouble for the Bronx than they resolved.

In many respects, Car 54, Where Are You? can be considered

somewhat of a sequel to the popular 1950s sitcom You’ll Never Get

Rich, which is also known as The Phil Silvers Show. That series,

created by writer-producer-director Nat Hiken and starring comedian

Phil Silvers as Sergeant Bilko, focused on the misadventures of an

oddball assembly of soldiers at Fort Baxter, a forgotten outpost in

Kansas. Hiken was a gifted writer who had worked on Fred Allen’s

A publicity shot from the television show Car 54, Where Are You?

CARAYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

433

radio show and later contributed to Milton Berle’s Texaco Star

Theater. The Silvers show had been a great hit as Sgt. Bilko and his

motor pool staff schemed, gambled, and tried to avoid all types of

work. When that series ended in 1959, Hiken decided to translate

some of its comic sensibility to another setting. Like its predecessor,

Car 54 was a series about men who failed to live up to the dignity of

their uniform. Unlike the schemers of Fort Baxter, however, the

police of the 53rd precinct were trying their best—though often

failing. Hiken filled the series with many performers featured on the

earlier show. Joe E. Ross had played Mess Sergeant Rupert Ritzik

‘‘the Lucretia Borgia of Company B.’’ The character of Gunther

Toody was an exact replica of the Ritzik character even down to his

trademark expression of ‘‘oooh-oooh-oooh.’’ Toody’s nagging wife

Lucille was played by Beatrice Pons, the actress who had appeared as

Mrs. Ritzik. Fred Gwynne, who had been a Harvard educated

advertising man, was also a featured player on the Bilko show.

Furthermore, many of the other officers had been seen as soldiers at

the mythical Fort Baxter.

The core of the series was the great friendship Toody and

Muldoon had forged from their many years patrolling the streets in

Car 54. Their contrasting natures had meshed perfectly despite the

fact they had absolutely nothing in common. Author Rick Mitz best

captured their relationship when he described the pair by noting,

‘‘Toody was the kind of guy who would say that he thought he should

get a police citation for ‘having the cleanest locker.’ Muldoon was the

kind of guy who would say nothing.’’ Many episodes took place away

from the police station and explored the partners’ home lives. Toody

and his frustrated wife often included the shy bachelor into their

evening plans. One of the series’ best episodes centered on Toody’s

mistaken idea that Lucille and Muldoon were having an affair.

Surrounding them was a cast of top character actors including Paul

Reed, Al Lewis, Charlotte Rae, Alice Ghostley, and Nipsey Russell.

Many of these performers would later graduate to star in their own TV

shows. All the characters on the program depicted an ethnic reality

little seen on early television. Toody’s Jewishness and Muldoon’s

Irish-Catholic background were more realistic than the bland charac-

ters, with no discernable heritage, seen on other programs. The series

was also distinguished by Hiken’s decision to film on the streets of

New York. Sets were constructed on the old Biograph Studio in the

Bronx. For street scenes, Toody and Muldoon’s patrol car was painted

red and white to indicate to New Yorkers that it was not actually a

police vehicle. In black-and-white film, Car 54’s unique colors

looked identical to the genuine New York police vehicles.

When it premiered in 1961, the series caused some controversy

after several police associations claimed it presented a demeaning

picture of police officers. The police department in Dayton, Ohio

dropped their own Car # 54 from the fleet after constant teasing from

the public. However, most viewers understood the series was intend-

ed as a satire that bore little relation to the lives of actual police

officers. Viewers’ affection for the show was evident in Nyack, New

York where a patrol car stolen from the police station parking lot was

nicknamed ‘‘Car 54.’’ The series ended in 1963 after failing to match

the success of Hiken’s earlier Phil Silvers program. Neither Nat

Hiken, who died in 1968, nor Joe E. Ross, who passed away in 1982,

ever again achieved the limited success they found with Car 54.

Following the show’s cancellation, Fred Gwynne and Al Lewis (who

played Sgt. Schnauzer) achieved TV immortality playing ‘‘Herman’’

and ‘‘Grandpa’’ on the monster sitcom The Munsters. Gwynne

died in 1993.

The sitcom Car 54, Where Are You? is an energetic series that

never really attained a mass audience. Its presentation of the misad-

ventures of Officers Toody and Muldoon gained a small cult audience

that only expanded after the series began to be replayed on cable’s

Nick at Night network. An awful 1994 movie version update of the

show (which was filmed in 1991) starred David Johansen and John C.

McGinley as Toody and Muldoon. It also featured rising stars Rosie

O’Donnell and Fran Drescher. Viewers of the original sitcom can

ignore the film and enjoy a quirky short-lived series that offers an

amusing update of the Keystone Kops. Furthermore, after one view-

ing it’s almost impossible to forget that opening theme, which

began: ‘‘There’s a holdup in the Bronx / Brooklyn’s broken out in

fights / There’s a traffic jam in Harlem that’s backed up to

Jackson Heights....’’

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim. The Complete Directory to Prime Time TV Stars. New

York, Ballatine Books, 1987.

Castleman, Harry, and Walter Podrazik. Harry and Wally’s Favorite

TV Shows. New York, Prentice Hall Press, 1989.

Mitz, Rick. The Great TV Sitcom Book. New York, Perigee, 1983.

Car Coats

Car coats originated in the United States in the 1950s with the

American migration to suburbia. Popular through the 1960s, they

were designed to be convenient for driving, at hip to three-quarter

length. Car coats were regulation outerwear: woollen, semi-fitted,

frequently double-breasted, with various design features such as

back-belts and toggles. The same coat is known to 1990s consumers

as the stadium, toggle, or mackinaw coat.

—Karen Hovde

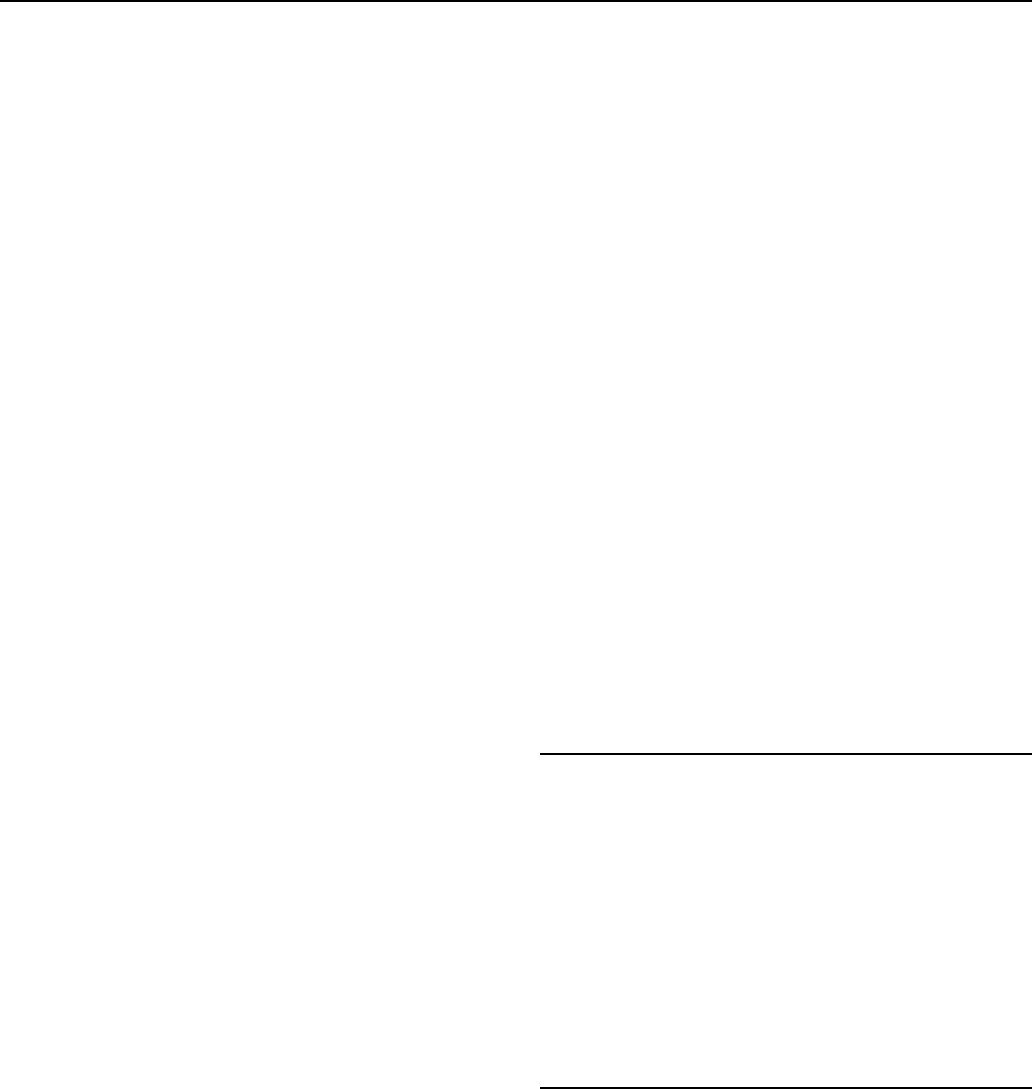

Caray, Harry (1919-1998)

In his 53 years as a Major League Baseball broadcaster, Harry

Caray’s boisterous, informal style, passionate support for the home

team, and willingness to criticize players and management made him

a controversial fan favorite; and towards the end of his career,

something of an anachronism. During his first 25 seasons (1945-69)

with the St. Louis Cardinals, KMOX’s 50,000 watt clear channel

signal and an affiliated network of small stations in the South,

Southwest, and Midwest gave Caray regional exposure. He is perhaps

best known for his catch phrase ‘‘Holy Cow,’’ and the sing-along-

with-Harry rendition of ‘‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame.’’ Caray

achieved national prominence when he moved to WGN and the

CAREY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

434

Harry Caray

Chicago Cubs in 1983. Cable television was then in its infancy, and

largely on the strength of its sports programming, WGN became one

of the first national superstations.

—Thomas J. Mertz

F

URTHER READING:

Caray, Harry, with Bob Verdi. Holy Cow. New York, Villard

Books, 1988.

Smith, Curt. Voices of the Game: The First Full-Scale Overview of

Baseball Broadcasting, 1921 to the Present. South Bend, Indiana,

Diamond Publishing, Inc., 1987.

Carey, Mariah (1970—)

An uproar of praise accompanied Mariah Carey’s 1990 musical

debut. Her first single, ‘‘Vision of Love,’’ immediately established

her as a major talent and showcased her trademark vocal sound: a

masterful, multi-octave range, acrobatic phrasing, ornamented vocal

trills, and uncanny, piercing notes in her upper vocal register. It was a

sound that was clearly influenced by soul music tradition, yet one that

Carey made uniquely her own. Unlike many popular singers, she

wrote or co-wrote much of her music. Because of her beautiful and

visually striking appearance, she gained additional popularity as a sex

symbol, appearing continually—often seductively or even scantily

dressed—in national magazines. She found great success year after

year, following her debut, and was, for nearly a decade, America’s

most popular musician.

—Brian Granger

F

URTHER READING:

Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. New York,

Billboard Publications, 1996.

Carlin, George (1938—)

During the 1960s, George Carlin revolutionized the art of stand-

up comedy. He employed observational humor, adding a comic twist

to everyday occurrences in order to comment on language, society,

sports, and many mundane aspects of American daily life. His

captivating stage presence and seemingly endless supply of material

enabled him to succeed in giving comedy concerts. Rarely before had

a comedian drawn such large crowds to a theater just to hear jokes.

George Carlin was born on May 12, 1938, in the Bronx, New

York City. With one older brother, Pat, George grew up in Morningside

Heights, which he calls ‘‘White Harlem,’’ and took the title of his

album Class Clown from his role in school as a child. He dropped out

of high school and enlisted in the Air Force. He ended up in

Shreveport, Louisiana, where he became a newscaster and DJ at radio

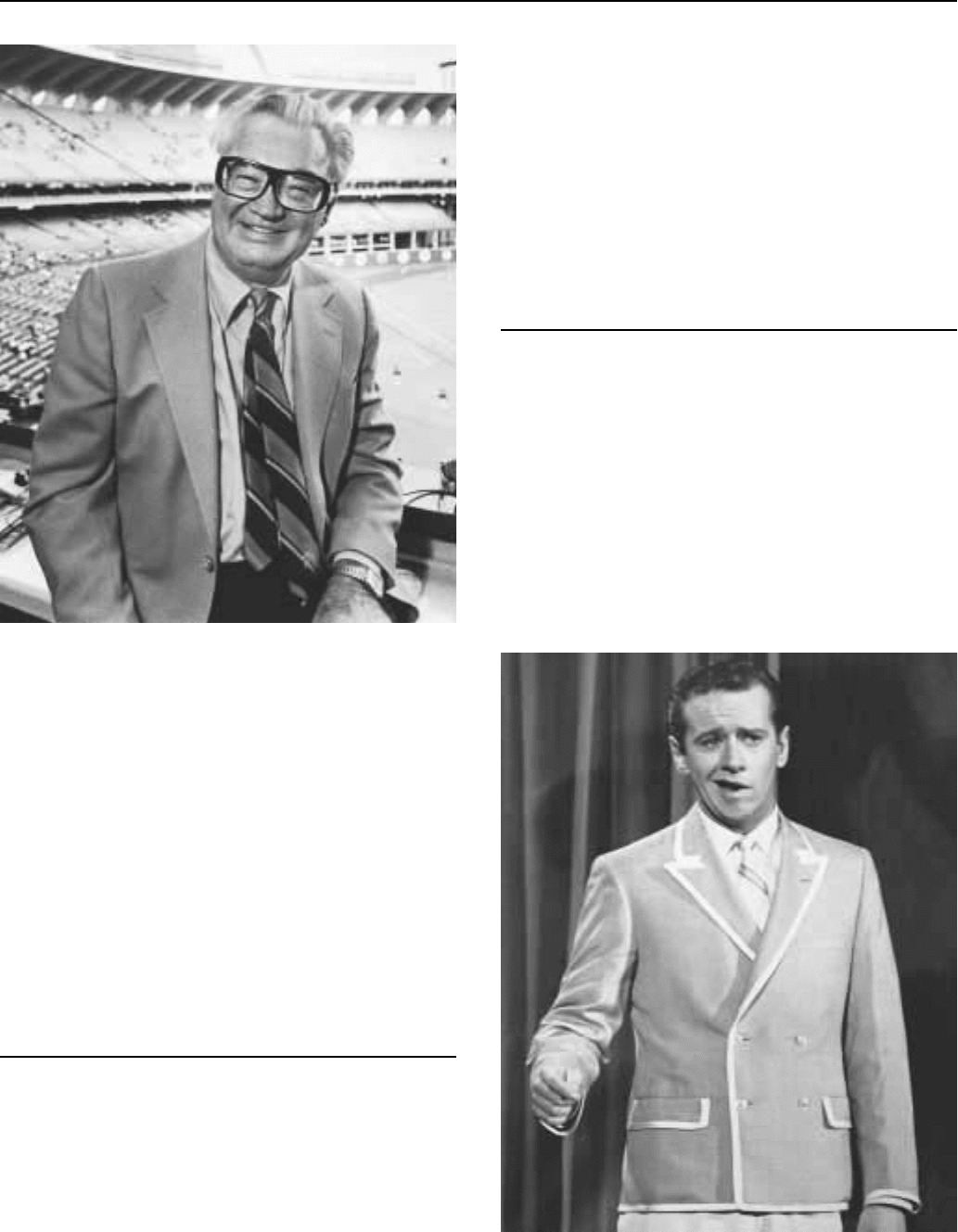

George Carlin

CARLTONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

435

station KJOE, while still serving in the Air Force, and after his

discharge continued worked in radio, moving to Boston in 1957

where he joined radio station WEZE.

Over the next few years, Carlin had many radio jobs, and in 1959

he met newsman Jack Burns at KXOL in Fort Worth, Texas. Teaming

with Burns in the early 1960s, he moved to Hollywood where he came

to the attention of Lenny Bruce. Burns and Carlin secured spots in

mainstream comedy clubs and made an appearance on The Tonight

Show with Jack Paar. When Jack Burns left the team to work with

Avery Shrieber, George Carlin began to make a name for himself as a

stand-up comedian, and during the decade became a fixture on

television, appearing on the Johnny Carson, Mike Douglas, and Merv

Griffin shows, and writing for Flip Wilson. His first comedy album,

Take-Offs and Put-Ons, came out in 1972.

Also in 1972, he was arrested after doing his ‘‘Seven Words You

Can Never Use on Television’’ routine at a Milwaukee concert. The

charges were thrown out by the judge, but George Carlin will forever

be associated with an important test of the First Amendment as

applied to broadcasting—the routine was later the crux of a Supreme

Court case, FCC v. Pacifica Radio, whose station WBAI in New York

City broadcast the offending album. The case helped launched the

FCC’s ‘‘safe harbor’’ policy, allowing profanity on the air only after

10 PM (later changed to midnight and then extended to a 24-hour ban

on indecent material).

Carlin continued releasing albums, Occupation: Foole, FM/AM,

and Toledo Window Box, among others, and earning Grammy awards.

Throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, Carlin kept a public career

in comedy going through television and movie appearances, record-

ings and live concerts, frequently performing at colleges and music

festivals. He has continued developing his particular brand of humor,

with its combination of satire, wordplay, and social commentary.

—Jeff Ritter

F

URTHER READING:

Carlin, George. Brain Droppings. New York, Hyperion, 1997.

———. Sometimes a Little Brain Damage Can Help. Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, Running Press, 1984.

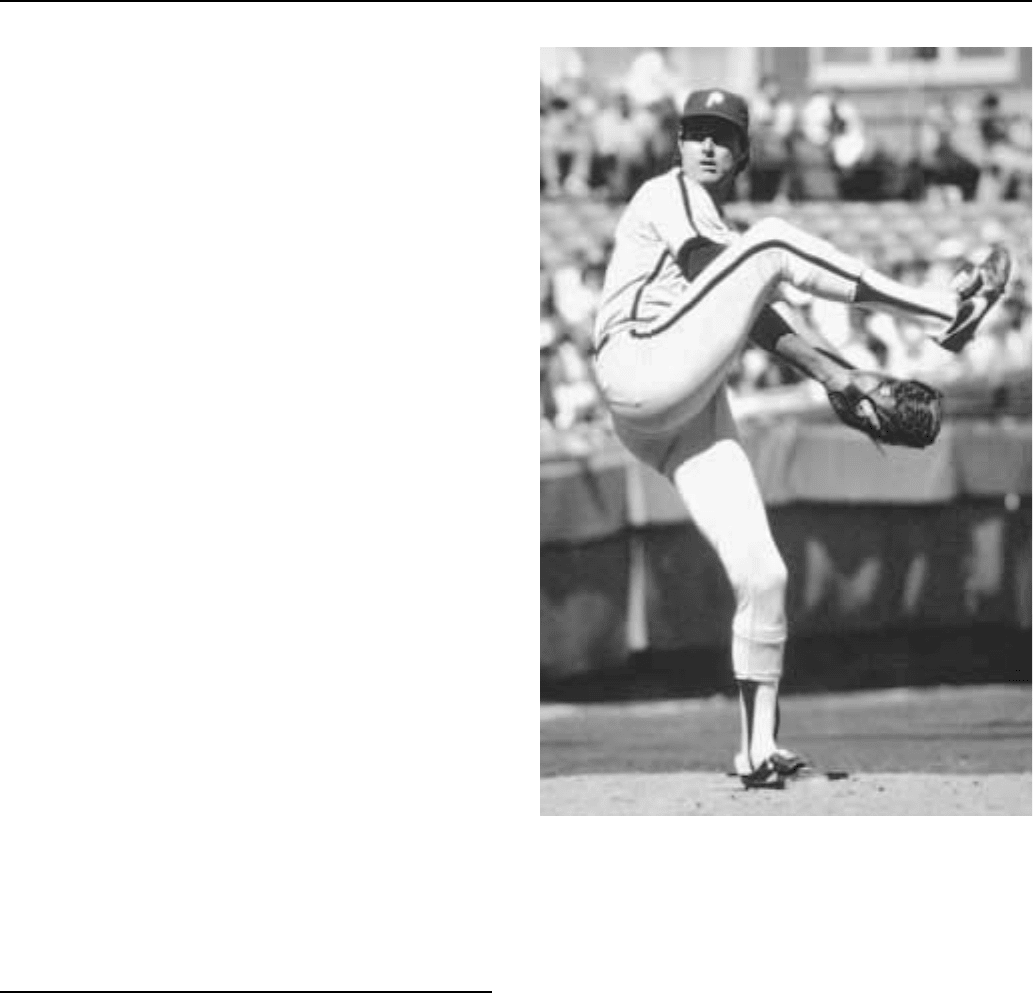

Carlton, Steve (1944—)

During the second half of his major league pitching career, Steve

Carlton did not speak to reporters, preferring to let his left arm do the

talking for him. Out of such determined resolve Carlton fashioned an

exceptional career that left him destined for the Baseball Hall of

Fame. A multiple Cy Young award winner, second only to Nolan

Ryan in career strikeouts, Carlton became the first major leaguer

since Robert Grove and Vernon Gomez to be universally known

as ‘‘Lefty.’’

A Miami native, Carlton signed with the St. Louis Cardinals

franchise and entered the major leagues in 1965. He became the

team’s number two starter, behind the fierce right-hander Bob Gib-

son, and helped the Cardinals to two pennants and the 1967 World

Series. Yet Carlton never seemed to get respect; even the 1969 game

when he struck out a then record nineteen New York Mets came

during a defeat. After a salary dispute with Cardinals management in

late 1971, he was traded to the woebegone Philadelphia Phillies for

Steve Carlton

pitcher Rick Wise. Wise was the only star on the perennial also-rans,

as well as the Phillies’ most popular player. Carlton responded to his

uncomfortable new surroundings with one of the most dominant

seasons in baseball history. While the 1972 Phillies won only 59

games, Carlton won 27, or nearly half his team’s total, all by himself.

During one stretch he won 15 games in a row. Combined with a 1.97

earned run average and 310 strikeouts, Carlton won his first National

League Cy Young Award.

As Carlton developed, gradually so did the Phillies, as Carlton

was joined by third baseman Mike Schmidt and, eventually, Tug

McGraw, and Pete Rose. Carlton led the team to six division titles and

two pennants between 1976 and 1983. And in 1980 his two victories

in the World Series gave the Phillies their first world championship.

Carlton was an efficient left-hander who routinely led the major

leagues by pitching nine-inning games in less than two hours and

twenty minutes. Hitting him, slugger Willie Stargell once lamented,

was like drinking coffee with a fork. Under the tutelage of Phillies

trainer Gus Hoefling, Carlton embarked on a rigorous physical

regimen, including karate, meditation, and stretching his left arm in a

bag of rice. He also stopped talking to the media in 1979, following a

feud with a Philadelphia columnist. While Carlton was loquacious

CARMICHAEL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

436

with teammates on many subjects (in particular his hobby, wine

collecting), he was mute to the press.

In 1983 and 1984, Carlton competed with the ageless Nolan

Ryan for bragging rights to the all-time career strikeout record.

Carlton held the top spot intermittently before Ryan pulled away in

1984. Carlton’s total of 4,136 strikeouts is still the second highest of

all time, and over 600 more than Walter Johnson’s previous record.

In 1982, the 37-year-old Carlton won 23 games and a record

fourth Cy Young Award. The next season, he won his 300th career

game and again led the league in strikeouts. With his sophisticated

training and focus, Carlton seemed capable of pitching in the major

leagues until he was 50. Unfortunately, his pitching ability faded with

age. He won only 16 games after his 40th birthday, and poignantly

moved from team to team in the last two seasons of his career before

retiring in 1988 with a won-loss record of 329-244.

Carlton’s election to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994 (in his

first year of eligibility) was marred by an incident weeks later. Ending

his silence with the press, Carlton gave a rambling interview in

Philadelphia Magazine from his mountainside compound in Colo-

rado, where he claimed that AIDS was concocted by government

scientists, that teacher’s unions were part of an organized conspiracy

to indoctrinate students, and that world affairs were controlled by

twelve Jewish bankers in Switzerland. Most Phillies fans ignored his

idiosyncratic political commentary, however, and attended his

Cooperstown induction that summer.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Aaseng, Nathan. Steve Carlton: Baseball’s Silent Strongman. Minne-

apolis, Lerner Publishing, 1984.

James, Bill. The Bill James 1982 Baseball Abstract. New York,

Ballantine, 1982

———. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York,

Villard, 1988.

Westcott, Rich. The New Phillies Encyclopedia. Philadelphia, Tem-

ple University Press, 1993.

Carmichael, Hoagy (1899-1981)

Children who play the perennial ‘‘Heart and Soul’’ duet on the

family piano might not realize that the tune was written in 1938 by one

of America’s most prolific popular song composers, Hoagy Carmichael.

Carmichael also became one of the century’s most iconic pianists, as

his distinctive appearance—gaunt and glum, hunched over the up-

right piano in a smoky nightclub—endures through numerous Holly-

wood films from the 1940s and 1950s, including classics such as To

Have and Have Not and The Best Years of Our Lives (in Night Song he

even shares billing with classical concert pianist Arthur Rubinstein).

Carmichael’s music lives on, too, having thoroughly entered the

American musical canon. Of his 250 published songs, ‘‘Stardust’’

(1927) is probably one of the most frequently recorded of all popular

songs (with renditions by artists ranging from Bing Crosby and Nat

King Cole to Willie Nelson and Carly Simon); ‘‘The Lamplighter’s

Serenade’’ (1942) proved to be Frank Sinatra’s solo recording debut;

and ‘‘Georgia on My Mind’’ (1931) has become that state’s

official song.

Hoagy Carmichael

Carmichael’s roots were in the 1920s Midwest, where traditional

Americana intersected with the exciting developments of jazz. Hoagland

Howard Carmichael was born on November 22, 1899, in Blooming-

ton, Indiana. His father was an itinerant laborer; his mother, an

amateur pianist, played accompaniment for silent films. In 1916, his

family moved to Indianapolis, where Carmichael met ragtime pianist

Reggie DuValle, who taught him piano and stimulated his interest in

jazz. In 1919 Carmichael heard Louis Jordan’s band in Indianapolis;

as Carmichael relates in his autobiography Sometimes I Wonder, the

experience turned him into a ‘‘jazz maniac.’’ While studying law at

Indiana University, Carmichael formed his own small jazz band, and

also met 19-year-old legendary cornetist Leon ‘‘Bix’’ Beiderbecke,

who became a close friend as well as a strong musical inspiration.

Carmichael’s earliest surviving composition, the honky-tonk ‘‘River-

boat Shuffle,’’ was written in 1924 and recorded by the Wolverines,

Beiderbecke’s jazz band (Carmichael, incidentally, wrote the soundtrack

music and played a supporting role in Hollywood’s 1950 fictionalized

version of Beiderbecke’s life, Young Man with a Horn, starring Kirk

Douglas, Lauren Bacall, and Doris Day).

After receiving his degree, Carmichael practiced law in Palm

Beach, Florida, hoping to capture part of the real estate boom market

there. Soon deciding to devote his efforts to music, Carmichael

moved to New York, but met with little success on Tin Pan Alley. It

was not until Isham Jones’s orchestra made a recording of ‘‘Stardust’’

in 1930 that Carmichael had his big break. Within a year Louis

Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and the Dorsey brothers had recorded

their own versions of other Carmichael songs (including ‘‘Georgia

CARNEGIEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

437

On My Mind,’’ ‘‘Rockin’ Chair,’’ and ‘‘Lazy River’’) for the

burgeoning radio audience.

During the next decade, Carmichael worked with lyricists John-

ny Mercer, Frank Loesser, and Mitchell Parish, among others. In the

late 1930s he joined Paramount Pictures as staff songwriter (his first

film song was ‘‘Moonburn,’’ introduced in the 1936 Bing Crosby

film Anything Goes), and also began appearing in films himself (the

first film he sang in was Topper, performing his own ‘‘Old Man

Moon’’). In 1944, ‘‘Hong Kong Blues’’ and ‘‘How Little We Know’’

were featured in the Warner Brothers film To Have and Have Not,

starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, which also marked

Carmichael’s debut as an actor. In one year (1946) Carmichael had

three of the top four songs on the Hit Parade, and in 1947 his rendition

of his own song ‘‘Old Buttermilk Sky’’ (featured in the film Canyon

Passage, and nominated for an Academy Award) held first place on

the Hit Parade for six consecutive weeks. Carmichael described his

own singing as a ‘‘native wood-note and flatsy-through-the-nose

voice.’’ It was not until 1952, however, that Carmichael and lyricist

Mercer won an Academy Award for Best Song with ‘‘In the Cool,

Cool, Cool of the Evening,’’ performed by Bing Crosby in Para-

mount’s Here Comes the Groom). Carmichael also made appearances

on television during the 1950s, hosting his own variety program, The

Saturday Night Revue (a summer replacement for Sid Caesar’s Your

Show of Shows), in 1953. In 1959 he took on a straight dramatic role as

hired ranch hand Jonesy on the television Western series Laramie.

Carmichael continued composing into the 1960s, but his two

orchestral works—‘‘Brown County in Autumn’’—and his 20-minute

tribute to the Midwest—‘‘Johnny Appleseed’’—were not as success-

ful as his song compositions. In 1971, Carmichael’s contributions to

American popular music were recognized by his election to the

Songwriters Hall of Fame as one of the ten initial inductees. He retired

to Palm Springs, California, where he died of a heart attack on

December 27, 1981.

—Ivan Raykoff

F

URTHER READING:

Carmichael, Hoagy. The Stardust Road. New York, Rinehart, 1946.

Carmichael, Hoagy, with Stephen Longstreet. Sometimes I Wonder:

The Story of Hoagy Carmichael. New York, Farrar, Staus, and

Giroux, 1965.

Carnegie, Dale (1888-1955)

Aphorisms, home-spun wisdom, and an unflagging belief in the

public and private benefits of positive thinking turned Dale Carne-

gie’s name into a household phrase that, since the 1930s, has been

uttered with both gratitude and derision. Applying the lessons that he

learned from what he perceived to be his failures early in life,

Carnegie began to teach a course in 1912. Ostensibly a nonacademic,

public-speaking course, Carnegie’s class was really about coming to

terms with fears and other problems that prevented people from

reaching their full potential. Through word of mouth the course

became hugely popular, yet Carnegie never stopped tinkering with

the curriculum, excising portions that no longer worked and adding

new material based on his own ongoing life experience. In 1936, he

increased his profile exponentially by publishing How to Win Friends

and Influence People, which ranks as one of the most purchased

books of the twentieth century. Although Carnegie died in 1955, his

course has continued to be taught worldwide, in virtually unchanged

form, into the late 1990s.

Carnegie (the family surname was Carnagey, with an accent on

the second syllable; Carnegie changed it when he moved to New

York, partly because of his father’s claim that they were distant

relatives of Andrew Carnegie and partly because the name had a

cachet of wealth and prestige) grew up on a farm in Missouri; his

family was, according to his own accounts, poverty-stricken. His

mother, a strict and devout Methodist, harbored not-so-secret hopes

that her son might become a missionary; some missionary zeal can be

seen in Carnegie’s marketing of his course. At the age of eighteen,

Carnegie left home to attend Warrensburg State Teacher’s College.

There, he made a name for himself as a riveting and effective public

speaker. Just short of graduating, he decided to quit and start a career

as a salesman in the Midwest. Despite his knack for expressing

himself, his heart was never in sales, and he was less than successful.

In 1910, Carnegie headed for New York City and successfully

auditioned for admission into the prestigious American Academy of

Dramatic Arts. The new style of acting taught at the school, radical for

its time, stressed sincerity in words and gestures. Students were

encouraged to emulate the speech and movement of ‘‘real people’’

and to move away from posturing and artificiality. Carnegie spent

even less time as a professional actor than he did as a salesman, but

this new method of acting would become a vital part of his course.

In 1912 Carnegie was back in sales, working for the Packard car

and truck company, after a disillusioning tour with a road company

that was staging performances of Molly Mayo’s Polly of the Circus.

Living in squalor and unable to make ends meet, Carnegie nonethe-

less walked away from his Packard sales job and began doing the one

thing he felt qualified to do: teach public speaking to businessmen.

The director of a YMCA on 125th Street in Harlem agreed to let

Carnegie teach classes on commission. (At that time most continuing

adult education took place at the YMCA or YWCA.) Carnegie’s

breakthrough came when he ran out of things to say and got the class

members to talk about their own experiences. No class like this had

ever been offered, and businessmen, salesmen, and, to a lesser extent,

other professionals praised the course that gave them the opportunity

to voice their hopes and fears, and the means to articulate them. Both

academic and vocational business courses were in short supply during

this time, and most professionals had little understanding of commu-

nications or human relations principles. Carnegie anticipated this

need and geared his course toward the needs of the business professional.

From 1912 until his death in 1955, Carnegie’s chief concern was

the fine-tuning and execution of his course, formally titled The Dale

Carnegie Course in Public Speaking and Human Relations, but fondly

known to millions of graduates as the ‘‘Dale Course.’’ Carnegie also

attempted to publish a novel, The Blizzard, which was ill-received by

publishers. His publishing luck changed in 1936, when Leon Shimkin

of Simon & Schuster persuaded him to write a book based on lectures

he gave in various sessions of the course. How to Win Friends and

Influence People was published in November of that year and became

an instant best-seller. Following this accomplishment, Carnegie pub-

lished a few similar works that also became bestsellers, most notably

How to Stop Worrying and Start Living. None of his subsequent

literary endeavors, however, matched the success of How to Win

Friends, although they are all used, to some extent, in his course.

With the huge sales of the book, Carnegie faced a new challenge:

meeting the growing public demand for the course. In 1939, he agreed

to begin licensing the course to other instructors throughout the

CARNEGIE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

438

Dale Carnegie

country. By now divorced from his first wife (the marriage ended

unhappily in 1931—Carnegie’s Lincoln the Unknown, with its unflat-

tering portrayal of Mary Todd Lincoln, was later revealed by the

author to be ‘‘largely autobiographical’’), he met Dorothy Vanderpool,

whom he would marry in 1941. Dorothy, a graduate of the Dale

Course, became an ardent supporter of her husband’s work and was

responsible for making the business a successful enterprise long after

her husband’s death. When she died, on August 6, 1998, the Dale

Carnegie Course, mostly unchanged in form and content, was still

going strong.

The Great Depression transformed Carnegie’s program from a

relatively successful endeavor into a cultural monument. His low-key

optimism and no-nonsense approach to human relations proved

irresistible to the massive number of Americans who were unem-

ployed. The publication of his book meant that his message, and his

appeal, could spread much further and faster than it had through the

auspices of the course. A year after its publication, the book’s title was

a permanent part of the language; the phrase ‘‘How to Win Friends

and Influence People’’ quickly overshadowed Dale Carnegie and his

course, and became a catch-phrase for enthusiasm borne of naiveté, as

well as a euphemism for manipulative styles of dealing with others.

Carnegie’s appeal was always complex and convoluted. His

book spoke to the hopes and fears of an entire nation beset by serious

economic difficulties, and yet many people thought his ideas were too

simplistic and out of tune with the times to take without a heavy dose

of irony. He had his share of famous critics as well, such as James

Thurber and Sinclair Lewis, who reviled How to Win Friends in their

writings. Apart from the high-minded criticism of these and other

intellectuals, the main obstacle that kept people from signing up for

Carnegie’s course was the same thing that won over many other

graduates: enthusiasm. The unbridled enthusiasm that was such a part

of the course, and that students demonstrated during open-house

sessions, could be off-putting as well as inspiring; people were unsure

whether it was contrived or real. There was a surge of renewed public

interest in the late 1980s, when Lee Iacocca revealed in his autobiog-

raphy the extent to which Carnegie’s course had influenced him and

his willingness to pay for his employees to take the course. In the end,

Carnegie’s sustained popularity was due as much to the controversy

caused by the public’s inability to take him completely seriously as to

the man’s teachings and writings.

—Dan Coffey