Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CASHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

449

Allen made his own tribute to Casablanca, entitled Play it Again Sam,

in which he wore a trenchcoat like Rick Blaine and repeated the

famous ‘‘Here’s looking at you, kid’’ speech in the context of a

narrative about sexual difficulties and masculinity. In this scenario,

Casablanca was recreated as a cult object which references Bogart

and his style of masculinity. Bogart’s character is said to have sparked

an onslaught on trench coat sales, and the image of him in the coat in

the original Warner Brothers poster purportedly launched the movie

poster business. In the late 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was an

important film on college campuses as cinema began to be viewed as a

serious art form. In the 1970s, a string of Rick Blaine-styled bars and

cafes began to appear in a variety of cities in the United States with

names like Play It Again Sam (Las Vegas), Rick’s Café Americain

(Chicago), and Rick’s Place (Cambridge, Massachusetts).

—Kristi M. Wilson

F

URTHER READING:

Eco, Umberto. ‘‘Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage.’’

In Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader, edited by David

Lodge. London and New York, Longman, 1988.

Francisco, Charles. You Must Remember This. . . : The Filming of

Casablanca. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1980.

Harmetz, Aljean. Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of

Casablanca: Bogart, Bergman, and World War II. New York,

Hyperion, 1992.

Koch, Howard. Casablanca. New York, The Overlook Press, 1973.

Lebo, Harlan. Casablanca: Behind the Scenes. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1992.

McArthur, Colin. The Casablanca File. London, Half Brick Im-

ages, 1992.

Miller, Frank. Casablanca, As Time Goes By. . . : 50th Anniversary

Commemorative. Atlanta, Turner Publishing, 1992.

Siegel, Jeff. The Casablanca Companion: The Movie and More.

Dallas, Texas, Taylor Publishing, 1992.

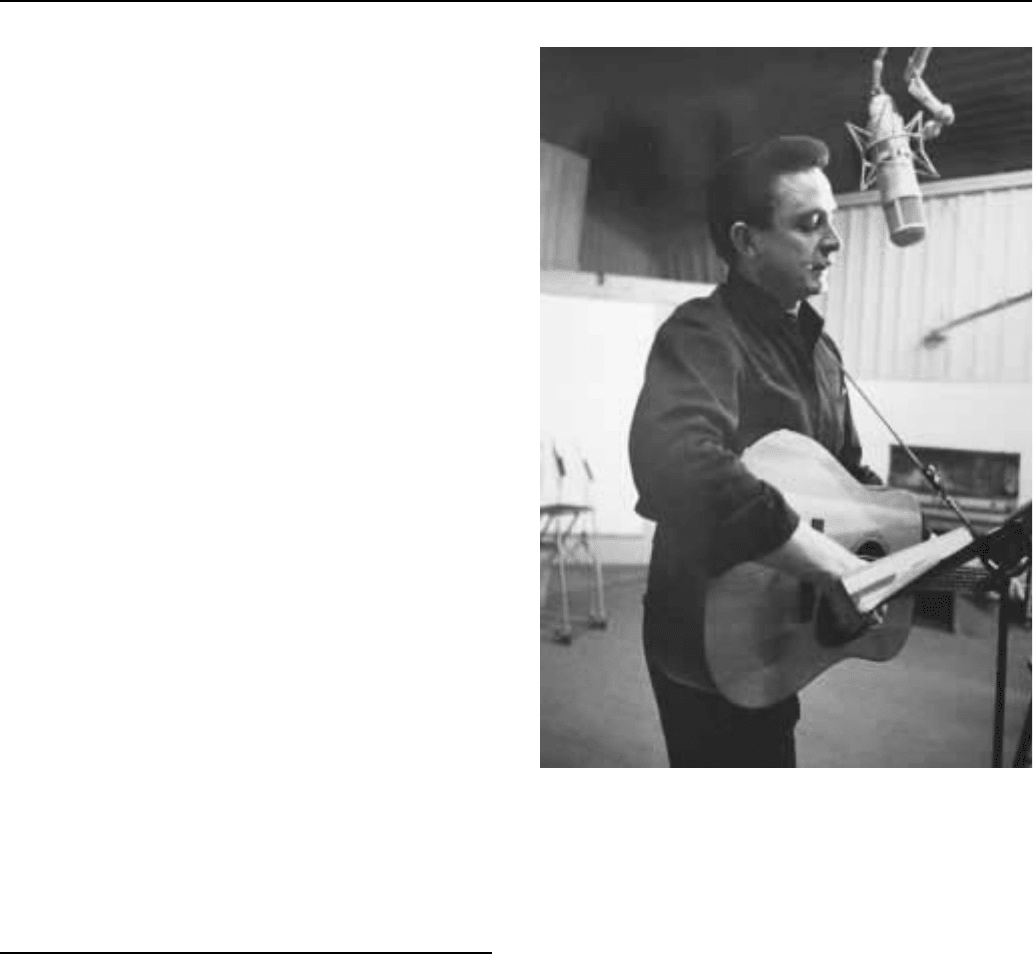

Cash, Johnny (1932—)

Significantly, country music star Johnny Cash’s career coincid-

ed with the birth of rock ’n’ roll. Cash’s music reflected the rebellious

outlaw spirit of early rock, despite the fact that it did not sound much

like the new genre or, for that matter, even like traditional country

music. Something that perhaps best sums up his image is a famous

picture of Cash, with a guitar slung around his neck and an indignant

look on his face giving the middle finger to the camera. As the self-

dubbed ‘‘Man in Black,’’ Johnny Cash has evolved from a Nashville

outsider into an American icon who did not have to trade his mass

popularity for a more mainstream, non-country sound. Despite a

number of setbacks, the most prominent of which was a debilitating

addiction to pills and numerous visits to jail, Cash has maintained his

popularity since releasing his first single in 1955.

Cash was born in Kingsland, Arkansas on February 26, 1932. He

grew up in the small Arkansas town of Dyess, a bible-belt town that

published Sunday school attendance figures in the weekly newspaper.

Cash hated working on the family farm, preferring instead to escape

into his own world listening to the Grand ’Ol Opry or its smaller

Johnny Cash

cousin, The Louisiana Hayride. By the age of 12 he was writing his

own songs and he also experienced what many claim to be his first

setback, perhaps fueling much of his reckless behavior—his brother

Jack was killed in a farming accident. In 1950, Cash enlisted in the Air

Force during the Korean War. It was during this time that he bought

his first guitar, taught himself how to play, and started writing

prolifically—one of the songs written during this period was the

Johnny Cash standard, ‘‘Folsom Prison Blues.’’ After his time in the

Air Force he married Vivian Leberto, moved to Memphis in 1954, and

began playing in a trio with guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist

Marshall Grant.

Johnny Cash’s first singles were released on Sam Phillips’

legendary Sun Records, the Memphis-based 1950s independent label

that also launched the careers of Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl

Perkins, and Elvis Presley. It was this maverick environment that

fostered Cash’s original sound, which was characterized by his

primitive rhythm guitar playing and the simple guitar picking of

Cash’s early lead guitarist, Luther Perkins. His lyrics overwhelmingly

dealt with the darker side of life and were delivered by Cash’s

trademark deep baritone voice that sounded like the aural equivalent

of the parched, devastated ground of the depression-era mid-west dust

bowl. ‘‘Folsom Prison Blues’’ was sung from the perspective of an

unrepentant killer and contained the infamous line, ‘‘I shot a man in

CASPAR MILQUETOAST ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

450

Reno just to watch him die.’’ Another prison song, ‘‘Give My Love to

Rose,’’ was a heartbreaking love letter to a wife that was left behind

when the song’s character was sent to jail. Other early songs like

‘‘Rock Island Line,’’ ‘‘Hey Porter,’’ ‘‘Get Rhythm,’’ and ‘‘Luther

Played the Boogie’’ could certainly be characterized as raucous and

upbeat, but Cash also had a tendency to write or cover weepers like

Jack Clement’s ‘‘I Guess Things Happen That Way,’’ the tragic

classic country ballad ‘‘Long Black Veil,’’ or his own ‘‘I Still

Miss Someone.’’

It was not long before Cash cultivated an outsider, outlaw image

that was exacerbated by his relatively frequent visits to jail— if only

for a day or two—for fighting, drinking, or possessing illegal am-

phetamines. The frequent concerts he played for prisoners inside jails

created an empathy between Cash and those at the margins of society.

The fact that he never shed his rural, working-class roots also created

a connection with everyday folks. His simple, dark songs influenced a

generation of country singer-songwriters that emerged in the early

1960s. They include Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Merle

Haggard. In fact, Haggard became inspired to continue playing music

after Cash gave a prison concert where Haggard was serving a two

year sentence for armed robbery.

Cash is a heap of contradictions: a devout Christian who is given

to serious bouts with drugs and alcohol; a family man who, well into

his sixties, spends the majority of the year on the road; and a loving,

kindhearted man who has been known to engage in violent and mean-

spirited behavior. His life has combined the tragic with the comic as

illustrated by a bizarre incident in 1983. During one of his violent

spells, he swung a large piece of wood at his eight-foot-tall pet ostrich,

which promptly kicked Cash in the chest, breaking three ribs. To ease

the pain he had to take painkillers. Cash had already spent time at the

Betty Ford clinic to end addiction to painkillers.

Cash’s career has gone through ups and downs. After an initial

burst of popularity during the Sun years, which fueled his rise to

country music superstardom on Columbia Records, his sales began to

decline in the mid-1960s, due partially to the debilitating effects of

drugs. During this period, Cash experienced a creative slump he has

not quite recovered from. For the most part he stopped writing his

own songs and instead began to cover the songs of others. After his

Sun period and the early Columbia years, original compositions

became more and more infrequent as he focused more on being a

performer and an interpreter rather than an originator. Although the

stellar music became increasingly infrequent, he still created great

music in songs like ‘‘Ring of Fire,’’ ‘‘Jackson,’’ and ‘‘Highway

Patrolman.’’ Despite countless albums of filler and trivial theme

albums— ‘‘Americana,’’ ‘‘Train,’’ ‘‘Gunfighter,’’ ‘‘Indian,’’ and

‘‘True West’’—there are still enough nuggets to justify his continued

recording career. This is true even in consideration of his lackluster

mid-1980s to the early 1990s Mercury Records years. In 1994,

however, Cash’s career was reignited again with the release of his

critically praised all-acoustic American Recordings, produced by

Rick Rubin. Rubin’s experience with Tom Petty, RUN-DMC, Red

Hot Chili Peppers, The Beastie Boys, and The Cult certainly prepared

him for a hit with Cash.

Meaning many things to many people, Cash has been able to

maintain a curiously eclectic audience throughout his career. For

instance, Johnny Cash was a hero to the southern white working

class—what some might call ‘‘rednecks’’—and college educated

northerners alike. He has cultivated an audience of criminals and

fundamentalist Christians—working closely, at times, with conserva-

tives like Billy Graham—and has campaigned for the civil rights of

Native Americans. During the late 1960s, he was embraced by the

counterculture and played with Bob Dylan on his Nashville Skyline

album, while at the same time performing for Richard Nixon at the

White House—Nixon was not the only president who admired

him . . . Cash even received fan mail from then president Jimmy

Carter. He has also been celebrated by the middle-American main-

stream as a great entertainer, and had a popular network television

variety show during the late 1960s and early 1970s called The Johnny

Cash Show.

During the 1990s, Cash has played both ‘‘oldies’’ concerts for

baby boomers and down home family revue-type acts, cracking

Southern flavored jokes between songs. During this time, Cash was

dismissed as a relic of a long-forgotten age by Nashville insiders who

profited from the likes of country music superstars Garth Brooks and

Shania Twain. After the release in 1994 of his American Recordings

album, however, he has been celebrated by a young hip audience as an

alternative rock icon and an original punk rocker.

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

Dawidoff, Nicholas. In the Country of Country: A Journey to the

Roots of American Music. New York, Vintage, 1997

Dolan, Sean. Johnny Cash. New York, Chelsea House, 1995.

Hartley, Allan. Hello, I’m Johnny Cash. New York, Revell, 1982.

Loewen, Nancy. Johnny Cash. New York, Rourke Entertainment, 1989.

Wren, Christopher S. Winner Got Scars Too: The Life and Legends of

Johnny Cash. New York, Ballantine, 1974.

Casinos

See Gambling

Caspar Milquetoast

Caspar Milquetoast was a comic strip character created by the

cartoonist Harold Tucker Webster (1885-1952) for the New York

Herald Tribune and other newspapers in the late 1920s. The central

figure in many of Webster’s witty, urbane, and mildly satirical

cartoons during the interwar years was frequently a middle-class

professional man who was rather mild-mannered and retiring. The

most notable and best known of these was Caspar Milquetoast, self-

effacing, obedient to a fault, and, quite literally, scared of his own

shadow—the personification of timidity. This character’s manner and

richly imagistic surname yielded the epithet ‘‘a milquetoast,’’ still

part of the American vernacular although it is unlikely that very many

of those who currently use the epithet have any knowledge of

its origin.

—John R. Deitrick

F

URTHER READING:

Webster, H.T. Best of H.T. Webster. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1953.

CASSETTE TAPEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

451

Cassette Tape

Compact, convenient, and easy to operate, the audio cassette

became the most widely used format for magnetic tape and dominated

the field for prerecorded and home-recorded music during the 1970s

and 1980s. Although superseded by digital players and recorders in

the 1990s, the cassette tape remains the dominant form of sound

recording worldwide.

Introduced in the 1940s, magnetic tape recording offered impor-

tant advantages over revolving discs—longer playback time and more

durable materials—but its commercial appeal suffered from the

difficulties that users experienced in threading the tape through reel-

to-reel tape recorders. One solution to this problem was the tape

cartridge, which came in either the continuous loop format or the two-

spooled cassette, which made it possible to rewind and fast forward

with ease. By the 1960s there were several tape cartridge systems

under development, including the four-track, continuous-loop car-

tridge devised by the Lear Company, the Fidelipac system used by

radio broadcasters, and the ‘‘Casino’’ cartridge introduced by the

RCA company for use in its home audio units. Tape cartridges also

were developed for the dictating machines used in business.

In 1962 the Philips Company developed a cassette using tape

half as wide as the standard 1/4-inch tape which ran between two reels

in a small plastic case. The tape moved half the speed of eight-track

tapes, getting a longer playing time but paying the price in terms of its

limited fidelity. The Philips compact cassette was introduced in 1963.

During the first year on the market, only nine thousand units were

sold. Philips did not protect its cassette as a proprietary technology

but encouraged other companies to license its use. The company did

require all of its users to adhere to its standards, which guaranteed that

all cassettes would be compatible. An alliance with several Japanese

A cassette tape.

manufacturers ensured that there were several cassette players avail-

able when the format was introduced for home use in the mid-1960s.

The first sold in the United States were made by Panasonic and

Norelco. The Norelco Carry-Corder of 1964 was powered by flash-

light batteries and weighed in at three pounds. It could record and play

back, and came complete with built-in microphone and speaker.

Public response to the compact cassette was very favorable,

encouraging more companies to make cassette players. By 1968

about eighty-five different manufacturers had sold more than 2.4

million cassette players worldwide. In that year the cassette business

was worth about $150 million. Because of worldwide adherence to

the standards established by the Philips company, the compact

cassette was the most widely used format for tape recording by the

end of the decade.

The fidelity of the cassette’s playback was inferior compared to

phonograph discs and the slower-moving reel-to-reel tape, conse-

quently the serious audiophile could not be persuaded to accept it. The

cassette had been conceived as a means of bringing portable sound to

the less discriminating user—a tape version of the transistor radio. It

was in this role that the cassette made possible two of the most

important postwar innovations in talking machines: the portable

cassette player or ‘‘boombox’’ and the personal stereo system with

headphones, introduced by Sony as the Walkman.

These highly influential machines were based on technological

advances in three fields: magnetic tape, batteries, and transistorized

circuits. For the first time, high-fidelity stereo sound and high levels

of transistorized amplification—capable of pouring out sound at ear-

deafening levels, hence the ‘‘boombox’’ name—could be purchased

in a compact unit and at a reasonable price. The portable cassette

player became one of the great consumer products of the 1970s and

1980s, establishing itself in all corners of the globe. Players were

incorporated into radios, alarm clocks, automobile stereos, and even

CASSIDY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

452

shower units. The ubiquitous cassette made it possible to hear

music anywhere.

The personal stereo was developed around the cassette and was

intended to be the ultimate in portable sound—so small it could fit

into a pocket. The stereo’s headphones surrounded the listener in a

cocoon of sound, eliminating much of the annoying noise found in

urban life but often at the price of damaging the hearing of the listener.

Since its introduction in 1979, Sony’s Walkman has been copied by

countless other manufacturers and can now be found in cassette and

digital formats, including compact disc and digital tape.

In the 1990s several digital tape formats were introduced to

compete with the audio cassette tape, and the manufacturers and

record companies did their best to phase out the elderly technology by

ceasing to manufacture both players and prerecorded tapes. Cassette

tape was ‘‘hisstory’’ said one advertisement for noise-free digital

recording, but consumers were unwilling to desert it. Although no

longer a viable format for prerecorded popular music (with the

exception of rap and hip-hop), cassette tapes live on in home

recording and in automobile use.

—Andre Millard

F

URTHER READING:

Kusisto, Oscar P. ‘‘Magnetic Tape Recording: Reels, Cassettes, or

Cartridges?’’ Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. Vol. 24,

1977, 827-31.

Millard, Andre. America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound.

Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Morita, Akio, E. Reingold, and M. Shimomura. Made in Japan: Akio

Morita and Sony. New York, Dutton, 1980.

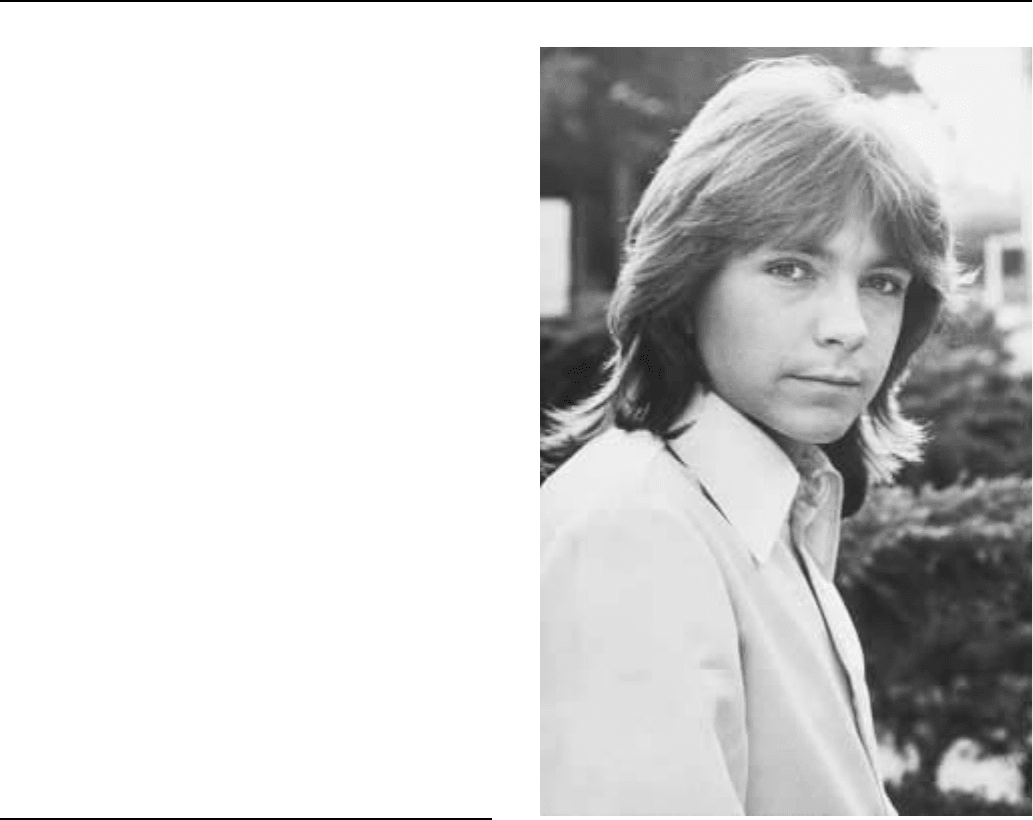

Cassidy, David (1950—)

David Cassidy may not have been the first teenage idol, but he

was the first to demand control of his life, walking away from the

entertainment industry’s star-machinery even as it went into over-

drive. And when that industry discarded him, Cassidy’s resolve to

return was more self-fulfilling than the first time around.

Cassidy was born on April 12, 1950, the son of actors Jack

Cassidy and Evelyn Ward. His parents divorced when he was three,

and David lived with his mother in West Orange, New Jersey. At 11,

Cassidy and his mother moved to Los Angeles, and David spent his

teen years hanging out in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury scene,

graduating from a private school and pursuing small acting jobs. He

moved to New York City in his late teens, working in a textile factory

by day and taking acting classes by night, before starring in the 1969

Broadway play, Fig Leaves Are Falling. With a stint on Broadway to

his name, Cassidy returned to Los Angeles and landed bit parts on

popular television shows.

The turning point came in 1969, when the ABC network was

casting for the musical comedy series, The Partridge Family, which

was based loosely upon the late 1960s folk-music family, the Cowsills.

David’s stepmother, actress Shirley Jones, was cast as the lead.

Unbeknownst to Jones, the producers had 19-year-old David read for

the part of the good-looking pop-music prodigy Keith Partridge.

Cassidy once claimed that when he was a child, his life was

changed forever upon seeing the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show. But

David Cassidy

that could never have prepared him for the tsunami of publicity

generated by the success of The Partridge Family. The show was a

runaway hit, and Cassidy’s visage was pinned up on teenage girls’

bedroom walls all over the country. The merchandising of Cassidy

remains a blueprint for the careers of all of the teen heartthrobs who

followed him. Posters, pins, t-shirts, lunchboxes, and magazine

covers proclaimed Cassidy-mania. He used the success of the show to

further his rock and roll career, playing to overflowing arena crowds

of teenage girls that were so hungry for a piece of their idol that

Cassidy had to be smuggled in and out of venues by hiding in laundry

trucks or the trunks of sedans.

After years of seven-day weeks running from television tapings

to recording studios to tour buses, the 23-year-old singer was starting

to feel the burn-out inevitably linked with fame. In a May, 1972, cover

story in Rolling Stone, Cassidy spoke candidly about his success,

bragging about taking drugs and having sex with groupies and—in a

moment of career suicide—railing against the pressures of his

chosen field.

During a 1974 concert in London, England, a 14-year-old girl

died of a heart attack. The rude awakening forced Cassidy to take a

long hard look at himself. His response was to retire from live

CASTANEDAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

453

performances and the television show in order to make a conscious

break from teeny-bopper fantasy to serious actor. Not long afterward,

The Partridge Family slipped in its ratings and was canceled; record

contracts were no longer forthcoming, and the window of opportuni-

ties available to Cassidy was closing quickly. He was free of the rigors

of show business, but industry professionals looked askance at his

quick rise-and-fall career.

The actor’s personal life was chaotic as well; his father, from

whom he had been estranged for nine months, died in a fire in his

penthouse apartment. Cassidy was drinking heavily at the time, and

found out that he was bankrupt. A 1977 marriage to actress Kay Lenz

lasted for four years; a second marriage to horse-breeder Meryl Tanz

in 1984 lasted just a year. He entered psychoanalysis soon after his

second divorce.

In 1978, Cassidy appeared in a made-for-TV movie, A Chance to

Live. The success of the movie prompted producers to create a spin-

off series titled David Cassidy: Man Undercover, which was poorly

received. In the late 1970s, he took the lead in a Broadway production

of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (ironically re-

placing drug-damaged teen idol Andy Gibb), and later ended up in

London’s West End theater district as the star of Dave Clarke’s play,

Time. While living in London, Cassidy recorded an album for the

Ariola label.

In the 1990s Cassidy devoted his time entirely to acting. In 1993,

he appeared with his half-brother Shaun Cassidy (himself a former

teen idol turned actor and producer) and British singer Petula Clark in

the stage drama Blood Brothers. In 1994, he wrote a tell-all memoir

about his television exploits entitled C’mon Get Happy: Fear and

Loathing on the Partridge Family Bus. In 1996, he helped relaunch

the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas, appearing in the science-

fiction musical variety show FX. While most teen idols stay forev-

er trapped in the history books, David Cassidy worked hard to

make sure he wasn’t trapped by a ‘‘sell-by’’ date like most

entertainment commodities.

—Emily Pettigrew

F

URTHER READING:

Allis, Tim. ‘‘The Boys Are Back.’’ People. November 1, 1993, 66.

Behind the Music: David Cassidy. VH-1. November 29, 1998.

Cassidy, David. C’mon, Get Happy: Fear and Loathing on the

Partridge Family Bus. New York, Warner Books, 1994.

‘‘Elvis! David!’’ New Yorker. June 24, 1972, 28-29.

Graves, R. ‘‘D-day Sound Was a High-C Shriek.’’ Life. March 24,

1972, 72-73.

Thomas, Dana. ‘‘Teen Heartthrobs: The Beat Goes On.’’ Washington

Post. October 3, 1991, C1.

Vespa, Mary. ‘‘Now Back Onstage, David Cassidy Has a New

Fiancee and a Confession: His Rock days Were No Picnic.’’

People. May 16, 1983, 75.

Castaneda, Carlos (1925-1998)

Little consensus has been reached about Carlos Castaneda,

whose books detailing his apprenticeship to the Yaqui Indian shaman

Don Juan Matus have sold over eight million copies in 17 languages

and contributed to defining the psychedelic counterculture of the

1960s as well as the New Age movement. Castaneda’s anthropologi-

cal and ethnographic credibility together with his intellectual biogra-

phy and personal life have been a constant source of puzzlement for

critics and colleagues. Castaneda himself contributed to complicate

the mystery surrounding his identity by supplying false data about his

birth and childhood and by refusing to be photographed, tape record-

ed, and, until a few years before his death (which was kept secret for

more than two months), even interviewed. In spite of (or perhaps

thanks to) Castaneda’s obsession with anonymity and several blunt

critical attacks on his works by anthropologists his international fame

has been long-lasting.

Born in Cajamarca, Perù (not in São Paulo, Brazil, as he

maintained), Castaneda became a celebrity almost overnight thanks

to the publication of The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of

Knowledge in 1968, when he was still a graduate student at the

University of California. In The Teachings of Don Juan as well as in

nine other books, Castaneda described the spiritual and drug-induced

adventures he had with the Yaqui Indian Don Juan, whom he

maintained to have met in 1960 while doing research on medicinal

plants used by Indians. During the course of the books, the author

himself becomes an apprentice shaman, sees giant insects, and learns

to fly as part of a spiritual practice that tends to break the hold of

ordinary Western perception. Castaneda defined his method of re-

search as ‘‘emic,’’ a term that was used in the 1960s to distinguish

ethnography that attempted to adopt the native conception of reality

from ethnography that relied on the ethnographer’s conception of

reality (‘‘etic’’). Because of several chronological and factual incon-

sistencies among the books and because Don Juan himself was never

found, many scholars agreed that Castaneda’s books were not based

on ethnographic research and fieldwork, but are works of fiction—

products of Castaneda’s imagination.

Jay Courtney Fikes pointed out that Castaneda’s books ‘‘are best

interpreted as a manifestation of the American popular culture of the

1960s.’’ The works of Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Gordon

Wasson stirred interest in chemical psychedelics such as LSD and

some of the psychedelic plants that Don Juan gave his apprentice

Castaneda, such as peyote and psilocybin mushrooms. These

psychedelics played an important part of the counterculture of the

1960s as a political symbol of defection from the Establishment.

Castaneda’s books contained exactly the message that the members of

the counterculture wanted to hear: taking drugs was a non-Western

form of spirituality. Several episodes in The Teachings of Don Juan

link taking psychedelic plants to reaching a higher spiritual realm:

Don Juan teaches Castaneda to fly under the influence of jimsonweed

and to attain magical powers by smoking a blend of psilocybin

mushrooms and other plants. Castaneda’s books met the demands of a

vast audience that was equally disappointed by anthropology as well

as by traditional religion.

In the early 1990s, Castaneda decided to become more visible to

the public in order to ‘‘disseminate Don Juan’s ideas.’’ He organized

New Age seminars to promote the teaching of Tensegrity, which he

described as ‘‘the modernized version of some movements called

magical passes developed by Indian shamans who lived in Mexico in

times prior to the Spanish conquest.’’ Castaneda, who at the time of

the seminars was dying of cancer, claimed that ‘‘practicing Tensegrity

. . . promotes health, vitality, youth and general sense of well-being,

[it] helps accumulate the energy necessary to increase awareness and

to expand the parameters of perception,’’ in order to go beyond the

limitations of ordinary consciousness.

CASTLE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

454

Carlos Castaneda’s death was just as mysterious as his life. His

adopted son claimed that he died while a virtual prisoner of the cult-

like followers of Cleargreen Inc., the group that marketed his works in

his late years. Castaneda was described by George Marcus and

Michael Fisher in Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimen-

tal Moment in the Human Sciences as an innovative anthropologist

whose books ‘‘have served as one of several stimuli for thinking

about alternative textual strategies within the tradition of ethnogra-

phy.’’ However, Jay Courtney Fikes, in Carlos Castaneda: Academic

Opportunism and the Psychedelic Sixties, called him a careless

ethnographer who ‘‘didn’t try diligently enough to distinguish be-

tween what was true and what was false.’’ Others condemned him as a

fraud and religious mythmaker for our post-modern era. Definitions

are difficult to apply to such an elusive personality. Paradoxically, the

best representation of Castaneda can be viewed in the portrait that

Richard Oden drew in 1972 and that Castaneda himself half-erased.

—Luca Prono

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Carlos Castaneda’s Tensegrity, Presented by Cleargeen Incorporat-

ed.’’ http://www.castaneda.org. May 1999.

DeMille, Richard. Castaneda’s Journey: The Power and the Allego-

ry. Santa Barbara, Capra Press, 1976.

Fikes, Jay Courtney. Carlos Castaneda, Academic Opportunism and

the Psychedelic Sixties. Victoria, Millennia Press, 1993.

Marcus, George, and Michael Fisher. Anthropology as Cultural

Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chi-

cago, University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Castle, Vernon (1887-1918), and

Irene (1893-1969)

Widely admired for their graceful dance routines and smart

fashion sensibilities, ballroom dancers Vernon and Irene Castle

spurred the national craze for new, jazz-oriented dance styles in the

years before World War I. In an age of widespread racism, the Castles

helped popularize African-American and Latin-American dances,

including the foxtrot and tango, previously considered too sensual for

white audiences. With the opening of their own dance school and

rooftop night club, the Castles became the darlings of New York City

café society. National dancing tours, movie appearances, and a steady

stream of magazine and newspaper articles swelled the couple’s

celebrity status to include increasing numbers of middle class men

and women. Often depicted as the most modern of married couples, it

was the Castles’ successful use of shared leisure activities to strength-

en their marriage, as much as their superior dance talents, that made

them the most popular dancers of their time.

—Scott A. Newman

F

URTHER READING:

Castle, Irene. Castles in the Air. Garden City, New York,

Doubleday, 1958.

Erenberg, Lewis A. Steppin’ Out: New York Nightlife and the

Transformation of American Culture, 1890-1930. Chicago, Uni-

versity of Chicago Press, 1981.

The Castro

Though the Castro district has been a distinctly defined neigh-

borhood of San Francisco since the 1880s, the district did not gain

worldwide fame until the 1970s when it became a mecca for a newly

liberated gay community—in effect a west coast equivalent to New

York’s Christopher Street. It has been said that if San Francisco is

America’s gay capital, Castro Street is its gay Main Street.

The Castro district had a rebellious reputation from its begin-

nings: the street was named in 1840 for General Juan Castro, who led

the Mexican resistance to white incursions into Northern California.

By the 1880s, Eureka Valley, as it was then called, was a bustling

working-class neighborhood, populated largely by Irish, German, and

Scandinavian immigrants. After World War II, many of the area’s

residents joined the widespread exodus to the suburbs, leaving empty

houses behind them. Coincidentally, post-World War II anti-gay

witch hunts resulted in the discharge of hundreds of gay military

personnel. Many were discharged in the port of San Francisco, and

others were drawn there by the comparatively open and tolerant

attitudes to be found there. Low housing prices in the unassuming

district around Castro Street attracted many of these migrants, and

gay bars began opening quietly in the 1950s. In 1960, the ‘‘gayola’’

scandal erupted in San Francisco when it was discovered that a state

alcohol-board official had taken bribes from a gay bar. The scandal

resulted in increased police harassment of gay bars but also sparked

pleas for tolerance from religious and city officials. It was this

reputation for tolerance that drew counterculture youth to San Fran-

cisco, culminating in the ‘‘Summer of Love’’ in 1967. Soon, thou-

sands of gay men and lesbians were finding the Castro district an

attractive place to live and open businesses, and during the 1970s the

Castro thrived as a gay civic center.

The 1970s were heady years for the gay and lesbian community.

Tired of the oppressive days of secrecy and silence, gay men created

the disco scene where they could gather to the beat of loud music, with

bright lights flashing. The new bars in the Castro, with names like

Toad Hall and the Elephant Walk, had big glass windows facing the

street, a reaction against the shuttered back-street bars of the 1950s.

Since the 1960s, more than seventy gay bars have opened in the

Castro. Many lesbians disavow the male-dominated Castro, however,

with its 70:30 male-to-female population ratio; they claim nearby

Valencia Street as the heart of the lesbian community.

Harvey Milk, a grassroots politician who would become the first

openly gay man elected to public office in a major city, played a large

part in creating the Castro phenomenon. Known as the ‘‘Mayor of

Castro Street,’’ Milk ran for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors

(city council) until he finally won in 1977. With an exceptional gift

for coalition politics, Milk forged alliances between gay residents and

the local Chinese community as well as with unions such as the

Teamsters, building bridges where divisions had existed, and mobi-

lizing the political influence of the thousands of gay men and lesbians

in the city. In November of 1978, Milk and San Francisco mayor Dave

Moscone were assassinated by a former city employee, Dan White.

When the gay community heard the news, a spontaneous outpouring

of Milk’s supporters took to the streets of the Castro, and thousands

CATALOG HOUSESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

455

marched there in a silent candlelight procession. Some weeks later,

when Dan White was sentenced to only seven years in prison, it was

not grief but anger that sent protesters into the streets for the ‘‘White

Night Riots.’’ Cars were torched and windows were smashed by

rioters; when they dispersed, the police followed them back to the

Castro in a rampage of violence that left sixty-one police and 100

protesters hospitalized.

Though the energetic early days of gay liberation are over, and

notwithstanding the heavy toll taken by the AIDS epidemic of the

1980s, the Castro is still a center of gay life in San Francisco, and

famous the world over. The district is renowned for its street festivals,

such as Gay Pride and the Castro Street Fair. The best-known party,

the Halloween bash, was moved in 1996 to the civic center at the

request of Castro merchants, who complained of rowdiness and

vandalism. The district has only half as many people of color as the

city at large, and the median age of residents is around thirty.

A walk down Castro Street in the 1990s still shows it to be very

gay identified, with gay symbols, such as the pink triangle and the

rainbow flag, adorning many stores and houses. Shops containing

everything from men’s haute couture fashions to leather-fetish dog

collars and leashes attract both residents and tourists. Whether it is

called a gay ghetto or a gay capitol, the Castro is clearly a political

entity to the city of San Francisco and a symbol of liberation for

the world.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Diaman, N.A. Castro Street Memories. San Francisco, Persona

Productions, 1988.

Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of

Harvey Milk. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1982.

Stryker, Susan, and Jim Van Buskirk. Gay by the Bay: A History of

Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco,

Chronicle Books, 1996.

‘‘Uncle Donald’s Castro.’’ http://www.backdoor.com/CASTRO/wel-

come.html. April 1999.

Vojir, Dan. The Sunny Side of Castro Street. San Francisco, Strawber-

ry Hill Press, 1982.

Casual Friday

Casual Friday, also called Dress Down Day, Casual Dress Day,

and Business Casual Day, is a loosening of the business world’s

unwritten dress codes on designated days. Employees trade suits, ties,

high heels, silk shirts, scarves, and other formal business attire for

slacks, sports coats, polo shirts, pressed jeans, loafers, knit tunics, and

flat-heeled shoes. Casual days arose in the mid-1980s influenced by

the jeans-T-shirt-sneakers uniform of the computer industry, as well

as increased numbers of women in the workplace and work-at-home

employees. The concept caught on in the early 1990s and, fueled

partly by Levi Strauss’s marketing, by the mid-1990s had become a

corporate institution. By the late 1990s, employees below middle

management in one third of U.S companies had gone casual five days

a week, according to an Evans Research Associates survey.

—ViBrina Coronado

F

URTHER READING:

Bureau of National Affairs. Dress Policies and Casual Dress Days.

PPF Survey no. 155. Washington, D.C., Bureau of National

Affairs, 1998.

Gross, Kim Johnson, and Jeff Stone and Robert Tardio. Work

Clothes—Casual Dress for Serious Work. Photographs by J. Scott

Omelianuk. New York, Knopf, 1996.

Himelstein, Linda, and Nancy Walser. ‘‘Levi’s vs. The Dress Code.’’

Business Week. April 1, 1996, 57-58.

Levi-Strauss & Company. How to Put Casual Businesswear to Work.

Version four. San Francisco, California, Levi-Strauss & Co.

Consumer Affairs, 1998.

Molloy, John T. ‘‘Casual Business Dress.’’ New Women’s Dress for

Success. New York, Warner Books, 1996, 209-249.

Savan, Leslie. ‘‘The Sell.’’ The Village Voice. April 16, 1996, 16-17.

Weber, Mark. Dress Casual for Success . . . for Men. New York,

McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Catalog Houses

Beginning with the first mail order catalog in the 1890s, people

have turned pages to weave together images of the perfect home or the

ideal wardrobe. From about 1900 through 1940, hundreds of thou-

sands of customers also selected their most important purchase, a

house, from a catalog. Catalog houses were essentially do-it-yourself

homebuilding kits. When a customer ordered a house through a

catalog, he or she received all of the parts, usually cut to length and

numbered for proper assembly, to build the selected home. In the first

half of the twentieth century, catalog houses helped meet a demand

for well-built, reasonably priced houses in America’s expanding

cities and suburbs.

Although pattern books and house plans had been widely

available throughout the mid-nineteenth century, catalog housing did

not begin in earnest until the early twentieth century with the founding

of the Aladdin Company in 1907. One of the longest-lived catalog

housing companies, Aladdin remained in business through 1983.

Robert Schweitzer and Michael W. R. Davis in America’s Favorite

Houses, a survey of catalog house companies, estimated that the

Aladdin Company sold 50,000 houses during its 76-year history.

Aladdin was soon joined by a number of national and regional

companies, including Gordon Van-Tine, Lewis Manufacturing Com-

pany, Sterling Homes, and Montgomery Ward. Probably the best

known producer of mail order and catalog homes was Sears, Roebuck

& Company, which sold homes through its Modern Homes catalog

from 1908 until 1940. In addition to these national companies, a

variety of regional and local companies also sold catalog houses.

A variety of factors contributed to the success of the companies

that sold houses through the mail. In the early decades of the twentieth

century, American cities were growing rapidly, due both to increased

foreign immigration and to migration from rural areas. According to

Schweitzer and Davis, the population of the United States increased

by 50 percent from 1890 to 1910. Much of this growth was in

American cities. As a result, there was a great demand for affordable,

well built houses. Catalog housing helped to meet this need.

In addition to the growth of urban areas, technological advances

made catalog houses possible. Steam-powered lumber mills made

CATALOG HOUSES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

456

lumber available year round, and the national railroad system enabled

building parts to be readily transported. This allowed the catalog

house companies both to create a nationwide system of suppliers and

made it possible to easily ship house components and other goods.

Sears owned lumber mills in Illinois and Louisiana, and a millwork

plant in Norwood, Ohio.

The catalog house companies did their utmost to insure that their

houses were ready to assemble. One of the innovations introduced by

Aladdin in 1911 and quickly adopted by other manufacturers were

parts that were ‘‘Readi-cut.’’ More than an advertising slogan, the

concept of lumber that was, as Sears called it, ‘‘already cut and

fitted,’’ meant that the structural components were precut to exact

lengths and ready for assembly. The benefits of this were many: The

do-it-yourselfer or contractor building the house did not have to spend

time on the job cutting the lumber to fit; it reduced wasted materials

and construction mistakes; and, in an age before power tools, it

simplified house building.

Part of the fascination with catalog houses in the late twentieth

century is how inexpensive they seem. In 1926 it was possible to buy a

six-room house from Sears for as little as $2,232. This price included

all of the lumber needed to construct the house, together with the

shingles, millwork, flooring, plaster, windows, doors, hardware (in-

cluding nails), the siding and enough paint for three coats. It did not

include the cost of the lot nor the labor required to build the house, nor

did it include any masonry such as concrete for the foundation. If the

house came from Sears, plumbing, heating, wiring, and storm and

screen doors and windows were not part of the original package, but

could, of course, be purchased from Sears at extra cost. The buyer of a

catalog house also received a full set of blue prints and a complete

construction manual.

One of the common elements of catalog houses was their design.

Catalogs from Sears, Roebuck & Co., Ray H. Bennett Lumber

Company, the Radford Architectural Company, and Gordon Van-

Tine show houses that seem nearly interchangeable. Bungalows,

American Four-Squares, and Colonial Revival designs dominate.

Sears regularly reviewed the design of its houses and introduced new

models and updated the more popular designs. A small four-room

cottage, the Rodessa, was available in 11 catalogs, between 1919 an

1933. The floor plan remained basically the same over the years

although details changed.

Sears had several sources for its house designs. The company

often bought designs for houses that had already been built and were

well received by the public. Sears also purchased designs from

popular magazines and reproduced those houses exactly. Beginning

in 1919, the company created its own in-house architectural division

that developed original house designs and adapted other contempo-

rary designs for sale by Sears. The Architects’ Council, as it was

called, became a selling point for Sears, which promoted the ‘‘free’’

architectural service provided to buyers of Sears’ houses.

Apart from reflecting the growth of city and suburb and the

growth of a mass market for housing, catalog houses were designed to

meet changing concepts of house and home. New materials, such as

linoleum, and laborsaving devices such as vacuum cleaners and

electric irons, made houses easier to manage. This reduced the need

for servants, which meant that houses could be smaller. At the same

time, lifestyles became less formal. The catalog house plans reflected

these changes, often eliminating entry vestibules and formal parlors.

The catalogs helped to reinforce and promote the interest in smaller

houses and less formal living spaces through their pages. Similar

ideas were promoted by popular magazines, such as Ladies’ Home

Journal, which sold house plans designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and

others, and organizations such as the American Institute of Architects,

which created the Small House Service Bureau, known as the

ASHB in 1919.

Advertising played an important role in the success of mail order

housing companies. The most effective tool used was annual catalogs.

The catalogs not only advertised the range of models available but

promoted the value of home ownership over paying rent, and provid-

ed the potential customer with testimonials and guarantees promoting

the quality of houses offered by each manufacturer.

The guarantees provided by the catalog firms were one of the

most effective tools used to promote their products. Sears provided a

written ‘‘Certificate of Guarantee’’ with each house; the guarantee

promised that sufficient materials of good quality would be received

to complete the house. Other companies offered similar guarantees of

quality and satisfaction; Aladdin, for example, promoted its lumber to

be ‘‘knot-free’’ by offering consumers a ‘‘Dollar-a-knot’’ guarantee.

Liberty offered its customers an ‘‘iron-clad guarantee,’’ while Lewis

had a seven-point protection plan.

In addition to their catalogs, the mail-order house companies

advertised in popular magazines, including the Saturday Evening

Post, Collier’s, and House Beautiful. Early in their history, the ads

were small and placed in the back pages of magazines; the emphasis

was to promote confidence in the products in order to develop a

market. The ads emphasized the cost savings, sound quality, and fast

delivery. Later ads were much larger and often consisted of a one- or

two-page spread emphasizing that the homes sold were both stylish

and well built.

Each of the catalog housing companies had their own philoso-

phy about providing financing. Sears first provided financing for its

houses in 1911. At first loans were for the house only; by 1918,

however, Sears began advancing capital for the labor required to build

the house. Eventually, Sears also loaned buyers the money to pay for

the lot and additional material. Other companies selling houses

through the mail were more conservative. Aladdin never provided

financing and required a 25 percent deposit at the time the order was

placed, with the balance due upon delivery. Sterling offered a 2

percent discount for customers paying in cash, as did Gordon-

Van Tine.

Sears vigorously promoted its easy payment plan throughout its

catalogs. The 1926 catalog includes an advertisement that assures the

reader that ‘‘a home of your own does not cost you any more than your

present mode of living. Instead of paying monthly rental, by our Easy

Payment Plan you may have . . . a beautiful home instead of worthless

rent receipts.’’ And, in the event that the reader missed the two-page

layout promoting Sears’ financing plan, each catalog page illustrating

a house plan included a reminder of the availability of the ‘‘easy

payment plan.’’

Just as a combination of conditions led to the initial success of

catalog houses, a number of factors contributed to their demise. The

company’s liberal financing policies are often cited as a contributing

factor in the death of Sears’ Modern Homes program. During the

depression of the 1930s, the company was forced to foreclose on

thousands of mortgages worth more than $11 million, and lost

additional money by reselling the houses below cost.

After World War II, social policy and technology passed by

catalog housing. There was no longer a niche for people who wanted

to build their own houses. The returning veterans and their brides

were anxious to return to normal lives, and they no longer had the time

or inclination to build their own houses. However, they did have the

CATCH-22ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

457

wherewithal to buy houses built by others. Subdivisions of builder-

constructed housing, beginning with Levittown, sprang up across the

country to meet this need. The builders of postwar housing capitalized

on the great demand by adapting Henry Ford’s assembly line princi-

ples to home construction. The desire for houses that were well built

disappeared in the need for houses that were quickly built.

—Leah Konicki

F

URTHER READING:

Gowans, Alan. The Comfortable House: North American Suburban

Architecture 1890-1930. Cambridge, Massachusetts, M.I.T.

Press, 1986.

Schweitzer, Robert, and Michael W. R. Davis. America’s Favorite

Homes: Mail Order Catalogues as a Guide to Popular Early 20th

Century Houses. Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1990.

Sears, Roebuck and Co. Sears, Roebuck Catalog of Houses, 1926: An

Unabridged Reprint. New York, Dover Publications, Inc. and

Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1991.

Stevenson, Katherine C., and H. Ward Jandl. Houses by Mail: A

Guide to Houses from Sears, Roebuck and Company. Washington,

D.C., Preservation Press, 1986.

Catch-22

Hailed as ‘‘a classic of our era,’’ ‘‘an apocalyptic masterpiece,’’

and the best war story ever told, Joseph Heller’s blockbuster first

novel, Catch-22 (1961), not only exposed the hypocrisy of the

military, but it also introduced a catchphrase to describe the illogic

inherent in all bureaucracies, from education to religion, into the

popular lexicon. The ‘‘Catch-22’’ of the novel’s title is a perverse,

protean principle that covers any absurd situation; it is the unwritten

loophole in every written law, a frustratingly elliptical paradox that

defies solution. As Heller demonstrates in his novel, Catch-22 has

many clauses, the most memorable of which allows only crazy men to

be excused from flying the life-threatening missions ordered by their

military superiors. To be excused from flying, a man needs only to ask

for release; but by asking, he proves that he is sane and therefore he

must continue flying. ‘‘That’s some catch,’’ observes one of the

flyers. ‘‘It’s the best there is,’’ concurs Doc Daneeka.

Heller drew deeply on his personal experiences in the writing of

his novel, especially in his depiction of the central character, Yossarian, a

flyer who refuses any longer to be part of a system so utterly hostile to

his own values. Like Yossarian, Heller served in the Mediterranean

during the later years of World War II, was part of a squadron that lost

a plane over Ferrara, enjoyed the varied pleasures that Rome had to

offer, and was decorated for his wartime service. And like Yossarian,

Heller passionately strove to become an ex-flyer. (After one of his

missions, in fact, Heller’s fear of flight became so intense that, when

the war ended, he took a ship home and refused to fly again for 15

years afterward.)

Although critics usually refer to Catch-22 as a war novel, the war

itself—apart from creating the community within which Yossarian

operates—plays a relatively small part in the book. While the military

establishment comprises an entire society, self-contained and abso-

lute, against which Yossarian rebels, it is merely a microcosm of the

Martin Balsam in a scene from the film Catch-22.

larger American society and a symbol for all other repressive organi-

zations. In the novel, there is little ideological debate about the

conflict between Germany and the United States or about definitions

of patriotism. Heller, in fact, deliberately sets Catch-22 in the final

months of the war, during which Hitler is no longer a significant threat

and the action is winding down. The missions required of the flyers

have no military or strategic importance except among the adminis-

trators, each of whom wants to come out of the war ahead. Inversely,

however, the danger to Yossarian from his superiors intensifies as the

war draws to a close. Yossarian wisely realizes that the enemy is

‘‘anybody who’s going to get you killed, no matter which side he’s

on.’’ And Heller surrounds Yossarian with many such enemies—

from generals Dreedle and Peckem, who wage war on each other and

neglect the men under their command; to Colonel Scheisskopf—

literally the Shithead in charge—who is so fanatic about military

precision that he considers implanting metal alloys in his men’s

thighbones to force them to march straighter; to Colonel Cathcart,

obsessed with getting good aerial photos and with making the cover of

the Saturday Evening Post, who keeps raising the number of requisite

flights; and Colonel Korn, who is so concerned that men might

actually learn something at their educational sessions that he imple-

ments a new rule: only those who never ask questions will be allowed

to do so. Entrepreneur extraordinaire and legendary double-dealer

Milo Minderbinder is a new age prophet of profit: he steals and resells

the morphine from flight packs and leaves instead notes for the

wounded soldiers that what is good for business is actually good for

them as well. (To prove his point, he notes that even the dead men

CATCHER IN THE RYE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

458

have a share in his ‘‘syndicate.’’) Captain Black insists that everyone

‘‘voluntarily’’ sign his Glorious Loyalty Oath, except his nemesis,

who will not be allowed to sign ‘‘even if he wants to.’’ And Nately’s

whore, out to avenge her lover’s death, persists in trying to kill the

innocent Yossarian. (In Heller’s logically illogical world, the whore is

symbolic of the universal principle that Yossarian will always be

unjustly beset upon—and will probably always deserve it.)

Yossarian’s increasingly dramatic acts of insubordination against

such an irrational system begin with his self-hospitalizations, where

he meets the ultimate symbol of the bureaucracy’s indifference to the

individual: the soldier in white, a faceless, nameless symbol of

imminent death. After his friend Snowden’s death, Yossarian’s

insubordination escalates to his refusal to fly or wear a uniform again,

and it ends with his decision not to compromise but instead to emulate

his comrade Orr’s impossible achievement and to affirm life by

rowing a small boat to Sweden.

In the film adaptation of Catch-22 (1970), by focusing

incrementally—as Heller did—on the Avignon incident during which

Snowden literally loses his guts and Yossarian metaphorically loses

his, director Mike Nichols succeeds in recreating the novel’s circu-

larity and its deliberately repetitive structure. By downplaying much

of the novel’s truculent satire of American capitalism, however,

Nichols is able to concentrate on the traumatizing fear of death, a

reality Yossarian (Alan Arkin) cannot face until he re-imagines it

through the death of Snowden (Jon Korkes). Nichols also reformu-

lates the well-intentioned capitalistic Milo Minderbinder; played by

baby-faced Jon Voight, the film’s Milo is a callous and sinister

destroyer of youth, every bit as corrupt as his superior officers, the

colonels Korn (Buck Henry) and Cathcart (Martin Balsam). Balanc-

ing the cynicism of the selfish officers is the affecting naïveté of their

victims, including the earnest Chaplain Tappman (Anthony Perkins),

the innocent Nately (Art Garfunkel), and the perpetually bewildered

Major Major (Bob Newhart).

An even more effective balance is the one Nichols strikes

between noise and silence: in sharp contrast to the busy confusion of

some of the film’s episodes, which aptly reflect the noisy chatter of

the novel and the jumble of word games Heller plays, there are subtle

moments of silence. The opening scene, for instance, begins in

blackness, without words or music; then there appears a tranquil

image of approaching dawn, replaced suddenly with the loud roar of

plane engines being engaged. It is as if the viewer is seeing the scene

through Yossarian’s eyes, moving with him from a dream state to the

waking nightmare (one of the film’s recurring motifs) of his reality.

Replete with inside jokes linking it to the Vietnam War (Cathcart’s

defecating in front of Chaplain Tappman, for instance, recalls LBJ’s

habit of talking to his aides while sitting on the toilet), Nichols’ film

adaptation of Catch-22 is thus an interesting and original work as well

as a noteworthy reinterpretation of Heller’s classic novel.

—Barbara Tepa Lupack

F

URTHER READING:

Heller, Joseph. Catch-22. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1961.

Kiley, Frederick, and Walter McDonald, editors. A Catch-22 Case-

book. New York, Thomas Y. Crowell, 1973.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. ‘‘Seeking a Sane Asylum: Catch-22.’’ In

Insanity as Redemption in Contemporary American Fiction.

Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 1995.

———, editor. Take Two: Adapting the Contemporary American

Novel to Film. Bowling Green, Popular Press, 1994.

Merrill, Robert. Joseph Heller. Boston: Twayne, 1987.

Merrill, Robert and John L. Simons. ‘‘The Waking Nightmare of

Mike Nichols’ Catch-22.’’ In Catch-22: Antiheroic Antinovel,

edited by Stephen W. Potts. New York, Twayne, 1989.

The Catcher in the Rye

The Catcher in the Rye, the only novel of the reclusive J. D.

Salinger, is the story of Holden Caulfield, a sixteen-year-old boy who

has been dismissed from Pencey Prep, the third time he has failed to

meet the standards of a private school. He delays the inevitable

confrontation with his parents by running away for a forty-eight hour

‘‘vacation’’ in New York City. A series of encounters with places and

people in the city serves to further disillusion Holden and reinforce

his conviction that the world is full of phonies. He plans to escape by

going West and living alone, but even his little sister Phoebe, the only

person with whom Holden can communicate, realizes that her brother

is incapable of taking care of himself. When Phoebe reveals her plan

to go with him, Holden accepts the futility of his escape plan and

goes home.

A focus of controversy since its publication in 1951, The

Catcher in the Rye has consistently appeared on lists of banned books.

The American Library Association’s survey of books censored from

1986 to 1995 found that Salinger’s novel frequently topped the list.

Just as consistently, however, the novel has appeared on required

reading lists for high school and college students. Critical views of

The Catcher in the Rye show the same polarization. Some critics have

praised its honesty and idiomatic language; others have faulted its

self-absorbed hero and unbalanced view of society. Holden Caulfield

has been called a twentieth-century Huck Finn, an autobiographical

neurotic, an American classic, and a self-destructive nut.

Through the decades, as the controversy has ebbed and flowed,

The Catcher in the Rye has remained a favorite with adolescent

readers who see their own experience reflected in Holden Caulfield’s

contempt for the ‘‘phoniness’’ of adult life. The very qualities that

lead some parents and other authorities to condemn Salinger’s

novel—the profanity, the cynicism, the preoccupation with sex—

predispose youthful readers to champion it. In Holden, adolescents

see the eternal outsider, sickened by the world around him, unable to

communicate the emotions that consume him, and aware that his

innocence has been irretrievably lost. It is a familiar image to many

adolescents. Arthur Heiserman and James E. Miller, Jr., in an early

essay on The Catcher in the Rye observed that Holden Caulfield is

unique among American literary heroes because he both needs to

return home and needs to leave home. But these conflicting needs,

while they may be unique in an American hero, are typical of

adolescents struggling to achieve a separate identity. Holden may be

faulted for his self-absorption, but in his consciousness of self, as in

his angst, the character is true to adolescent experience.

Even the obscenities and profanities that Holden speaks, a major

cause of official objections to the novel, affirm his status as

quintessential adolescent. He sees obscene speech as the only valid