Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CATHERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

459

response to the obscene hypocrisies of the profane adult world. The

irony, of course, is that Holden himself has already been contaminat-

ed by the world he despises. The child of affluent parents, he clearly

enjoys the benefits their ‘‘phony’’ world affords him. He spends

money on taxi rides and nightclub visits, and even as he condemns lies

and fakery, he himself lies and participates in the fakery. He is

acquiring the survival skills that will allow him to operate in the fallen

adult world, a fact he himself acknowledges: ‘‘If you want to stay

alive, you have to say that stuff.’’

Critics often classify The Catcher in the Rye as a quest story, but

Holden’s quest, if such it be, is aimless and incomplete. Holden’s

New York misadventures occur during the Christmas season, a time

when Christendom celebrates the birth of a child who became a

savior. But the Holy Child has no place in this world where the cross

that symbolizes his sacrifice has become merely a prop carried by

actors on a Radio City stage. A self-proclaimed atheist, Holden

inhabits a world where true transcendence can never be achieved. Yet

longing for a heroic role, he dreams of being the ‘‘catcher in the rye,’’

of saving ‘‘thousands of little kids’’ from plunging over the cliff into

the abyss of adulthood. Ultimately, however, as he comes to realize

while watching his little sister Phoebe circling on the carousel in

Central Park, children cannot be saved from adulthood. Only the dead

like his younger brother Allie are safe. Heroes belong in coherent

worlds of shared values and meaningful connections; Holden’s world

is the waste land, all fragments and dead ends. Would-be heroes like

Holden are ‘‘crazy mixed-up kids’’ who end up in California institutions.

The Catcher in the Rye is most frequently compared to Mark

Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, another account of an

adolescent male’s escape from the confinement of education and

civilization. The similarities between the two novels are obvious. The

narrator/protagonist in each is a teenage boy who repudiates adult

hypocrisies and runs away in search of a less flawed world; both

youthful protagonists speak in richly idiomatic language, and both are

comic figures whose humor sometimes offers grim truths. But Huck’s

longing for freedom is undiluted by dreams of saving others, and

Huck’s world has a duality that Holden’s slick society lacks. For

Huck, the corruptions on land are balanced by the ‘‘free and easy’’

life on the raft. Huck has the Mississippi; Holden has a duck pond.

Huck’s abusive father is balanced by the tenderness and concern of

Jim; Holden’s father is irrelevant, a disembodied payer of bills. Other

adult figures who have the potential to nurture Holden through his

crisis are mere passing images like the nuns to whom he gives money

or phony betrayers like Mr. Antolini who seems to offer Holden

compassion and understanding only to make sexual advances to him

later. His peers offer Holden no more than do the adults. They too are

phonies, like the pseudo-sophisticated Carl Luce and Sally Hayes, or

absent, idealized objects like Jane Gallagher.

Nowhere is Holden more clearly a creature of his time than in his

inability to connect, to communicate. The Catcher in the Rye is filled

with aborted acts of communication—truncated conversations, failed

telephone calls, an unconsummated sexual encounter. Most of the

things which awaken a sense of connection in Holden are no longer

part of the actual world. The precocious Allie who copies Emily

Dickinson poems on his baseball glove, the museum mummy, even

Ring Lardner and Thomas Hardy, the writers Holden admires and

imagines that he would like to call up and talk to—all are dead. In a

particularly revealing moment Holden fantasizes life as a deaf-mute,

a life that would free him from ‘‘useless conversation with any body’’

and force everyone to leave him alone. Yet this fantasy indicates

Holden’s lack of self-knowledge, for his isolation would be an act, his

deaf-muteness a pretense. He defines alienation as a job in a service

station and a beautiful, deaf-mute wife to share his life. Therein lies

the pathos of Holden Caulfield. He can neither commit to the inner

world and its truths nor celebrate the genuine that exists amid the

phoniness of the public world. The Catcher in the Rye, for all its

strength, fails as a coming of age story precisely because its protago-

nist, who is terrified of change, never changes. Mark Twain’s Huck

Finn sets out for the territory and freedom, James Joyce’s Stephen

Dedalus experiences his epiphany, T. S. Eliot’s Fisher King hears the

message of the thunder. J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield can only, as

he himself says at the novel’s end, ‘‘miss everybody.’’

—Wylene Rholetter

F

URTHER READING:

Bloom, Harold, ed. Holden Caulfield. New York, Chelsea House, 1990.

Engel, Stephen, ed. Readings on the Catcher in the Rye. San Diego,

Greenhaven, 1998.

Pinsker, Sanford. The Catcher in the Rye: Innocence Under Pressure.

New York, Twayne, 1993.

Salinger, J. D. The Catcher in the Rye. Little Brown, 1951.

———. Franny and Zooey. Little Brown, 1961.

———. Nine Stories. Little Brown, 1953.

———. Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenter and Seymour: An

Introduction. Little Brown, 1963.

Salzberg, Joel, ed. Critical Essays on Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye.

New York, Macmillan, 1989.

Salzman, Jack, ed. New Essays on the Catcher in the Rye. Cambridge

and New York, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Cather, Willa (1873-1947)

Willa Cather, variously perceived by critics as realistic, regionalist,

or sentimental, as well as an unusual literary stylist of unhurried

elegance, memorably exploited themes long regarded as part of the

American mythos. She wrote 12 novels and over 60 short stories,

contrasting nature’s wilderness with the social veneer of her charac-

ters, and achieved critical and popular acclaim for works such as O

Pioneers! (1913) and My Antonia (1918), which depict the Nebraska

frontier, and, most famously and enduringly perhaps, her ‘‘Santa Fe’’

novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), which treats the

history of the Southwest after the Mexican War. According to Susan

Rosowski, Cather ‘‘saw herself as the first of a new literary tradition,

yet one which evolved out of the past and from native traditions rather

than in revolt against them.’’ Novels like O Pioneers!, The Song of the

Lark (1915), and My Antonia favor cultural diversity as embodied in

the experiences of immigrant settlers, and showcase the strength of

their heroic female characters Alexandra Bergson, Antonia Shimerda,

CATHY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

460

and Thea Kronborg, respectively. Cather’s work also affirms appre-

ciation for a simpler era when America espoused spiritual ideals. In

the 1920s, in novels such as One of Ours (1922), A Lost Lady (1923),

and The Professor’s House (1925), she indicted a society that had

rejected revered traditional values to embrace materialism. Her last

novels—Shadows on the Rock (1931) and Sapphira and the Slave

Girl (1940)—reflect the writer’s retreat to a past further removed

from her own time, when order, stability, and noble principles

governed human life. Born in Virginia and educated at the University

of Nebraska, Cather wrote poetry, and spent six years as a journalist

with McClure’s magazine before devoting her life full-time to fiction.

She spent 40 years until her death living in New York with her

devoted companion Edith Lewis.

—Ed Piacentino

F

URTHER READING:

O’Brien, Sharon. Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice. New York,

Oxford University Press, 1987.

Rosowki, Susan J. The Voyage Perilous: Willa Cather’s Romanti-

cism. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

Woodress, James. Willa Cather: A Literary Life. Lincoln, University

of Nebraska Press, 1987.

Cathy

The comic strip Cathy, by American artist and writer Cathy

Guisewite, addresses the insecurities and desires of a new generation

of women trying to balance traditional pressures with the responsibili-

ty of careers and other personal freedoms. Premiering in November of

1976, Cathy introduced a character struggling with a mother urging

marriage and children, a demanding boss, a noncommittal boyfriend,

and a loathing for her figure. Although Guisewite was instrumental in

bringing women’s issues to the daily comics, Cathy also has its

detractors who long for a less scattered, more self-confident female

character. Nevertheless, Cathy has grown to syndication in more than

1,400 newspapers and has spawned books, television specials, and a

line of merchandise.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Friendly, Jonathan. ‘‘Women’s New Roles in Comics.’’ New York

Times. February 28, 1983, p. B5.

Moritz, Charles, editor. Current Biography. New York, H.W.

Wilson, 1989.

Sjoerdsma, Ann G. ‘‘Guisewite Could Be a Stronger, More Profound

Voice for Single Women.’’ Knight-Ridder/Tribune News Service.

August 15, 1997.

Cats

By the end of the twentieth century, Cats had lived up to its

billing of ‘‘Now and Forever,’’ as it became the longest-running

Andrew Lloyd Webber musical in both London and New York. The

tuneful score, inspired by T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical

Cats, includes songs in a wide variety of styles. John Napier’s

elaborate set transforms the entire theater into a garbage dump upon

which the feline cast learn which one of them will gain an extra life at

the Jellicle Ball. Various cats tell their tales through song, but the

winner is Grizabella, the glamour cat who became an outcast.

Grizabella’s number, ‘‘Memory,’’ is one of Lloyd Webber’s most

famous songs; by 1992, it had been recorded in no fewer than 150

different versions. Cats opened in London in 1981 and in New York

the following year. The innovative costumes and choreography

coupled with the eclectic musical score which culminates in ‘‘Memo-

ry’’ account for its continued popularity. A video version of Cats,

filmed during a London performance, was released in 1998.

—William A. Everett

F

URTHER READING:

Lloyd Webber, Andrew. Cats: The Book of the Musical. Lon-

don, Faber & Faber, 1981; San Diego, Harcourt, Brace, and

Jovanovich, 1983.

Richmond, Keith. The Musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber. London,

Virgin, 1995.

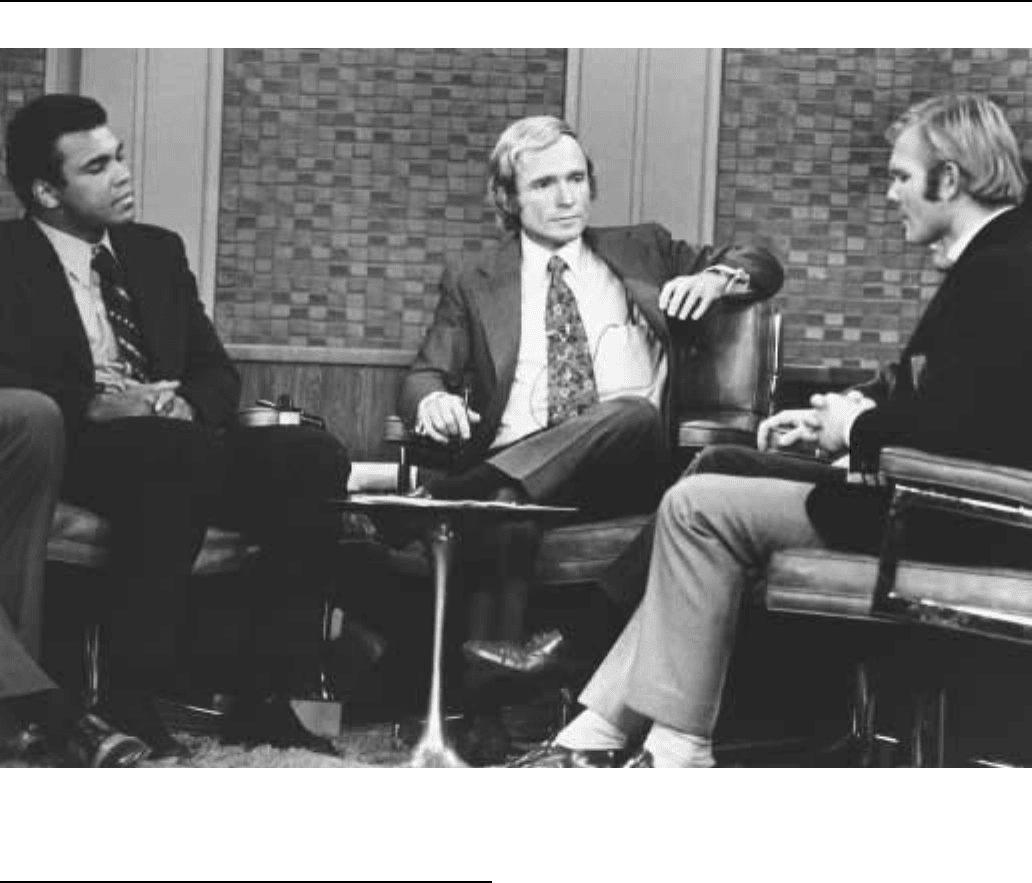

Cavett, Dick (1936—)

‘‘Sophisticated,’’ ‘‘witty,’’ ‘‘urbane,’’ ‘‘intelligent,’’ and ‘‘lit-

erate’’ are among the adjectives commonly used to describe Dick

Cavett, the Nebraska-born talk show host who experienced fame

during a relatively brief period of his early career and professional

struggle thereafter. The Dick Cavett Show was seen five nights a week

for seven years on ABC-TV from 1968 until 1975 and then once

weekly on Public Television until 1982. Cavett won three Emmy

awards during these years. His interviews with such individuals as

Lawrence Olivier, Katharine Hepburn, Noel Coward, Orson Welles,

Groucho Marx, and Alfred Hitchcock are classics in the field, as

Cavett’s lively mind allowed a degree of candor and spontaneity

generally lacking in the attempts of less gifted colleagues. For many

viewers, his show was the saving grace of commercial television and

a good reason to stay up late.

A Yale graduate, Cavett began his career as an actor and standup

comic without great success. While working as a copy boy for Time

magazine in 1960, he decided to try his hand at comedy writing. Since

Jack Paar was one of his early idols as a performer, he wrote a series of

jokes designed for Paar’s opening monologue on the Tonight Show

and finagled a plan to deliver the jokes directly to Paar. The plan

succeeded, Paar liked the jokes, and Cavett landed a job writing for

the show. From the Paar show, he got his first chance as a talk-show

host on morning television and soon moved on to his spot opposite

Johnny Carson (Paar’s successor) on ABC.

After the Cavett show’s demise, its host found various other

venues but never again reached the same level of visibility. An

attempted variety show series predictably fell flat, as scripted sketch-

es were not Cavett’s metier. Through the years since 1982, he has

CAVETTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

461

The cast of Cats.

hosted numerous talk shows on cable stations including Showtime

and CNBC, taken cameo roles in the theater, and narrated a PBS series

on Japan. His gift for conversation keeps him popular on the lecture

circuit, and his clear, uninflected Midwestern diction makes him an

ideal candidate for commercial voice-overs. In short, Cavett has kept

relatively busy, but his varied activities go mostly unnoticed by the

general public.

Cavett’s name came into the news in 1997 when he was sued for

breach of contract over a syndicated radio talk show he was scheduled

to host. He left the show after two weeks, and word went out through

his lawyer that Cavett’s premature departure was due to a manic-

depressive episode. The civil suit was eventually dismissed.

Prior to this turn of events, Cavett had been relatively open about

his chronic suffering with depression, even going on record about his

successful treatment with controversial electroconvulsive (otherwise

known as ‘‘shock’’)therapy. As a spokesperson on psychiatric illness,

Cavett, like William Styron, Art Buchwald, and others, has put his

verbal skills to use in articulating his experiences with the disease that

has plagued him intermittently throughout his career. He recalls, for

instance, in an interview for People magazine, a time before his ‘‘big

break’’ when he was living alone in New York City, and ‘‘I did

nothing but watch Jack Paar on The Tonight Show. I lived for the Paar

show. I watched it from my bed on my little black-and-white set on

my dresser, and I’d think, ‘I’ll brush my teeth in a minute,’ and then

I’d go to sleep and wake up at three the following afternoon.’’ It is

ironic that this brilliant conversationalist, the life of a sophisticated

nightly party, would once again enter the public eye by virtue of

his melancholia.

—Sue Russell

F

URTHER READING:

Cavett, Dick, and Christopher Porterfield. Cavett. New York, Harcourt

Brace, 1974.

———. Eye on Cavett. New York, Arbor House, 1983.

Cavett, Dick, and Veronica Burns. ‘‘Goodbye, Darkness.’’ People,

August 3, 1992, p. 88.

CB RADIO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

462

Dick Cavett (center) with Muhammad Ali and Juergen Blin on The Dick Cavett Show.

CB Radio

The Citizens Band Radio, familiarly known as the CB, was a

device that enabled free mobile communication up to a ten mile radius

for those who owned the requisite microphone, speaker, and control

box. Although the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) first

introduced it in 1947, the CB did not experience its heyday until 30

years later, when hundreds of thousands of automobile and tractor

trailer drivers installed them in their vehicles.

In order to popularize the device among individuals for their

personal use, the FCC, in 1958, opened up part of the broadcasting

spectrum originally reserved for ham radio operators. This Class D

band enabled the manufacture of higher quality, less expensive CB

sets that were useful and affordable to ordinary people. By 1959 the

average set cost between $150 and $200, but there were only 49,000

users licensed with the FCC. From 1967 to 1973, the FCC registered

about 800,000 licensees. Although one did not need to obtain a license

to operate a CB radio, the number of licensees shot up dramatically

from 1973 to the end of the decade, when more than 500,000 people

were applying for licenses each month in direct response to cultural

shifts at the time. The Vietnam War had ended with America less than

victorious; the Watergate scandal rocked the Nixon White House; and

the oil crisis from 1973 to 1974 led to a capping of national speed

limits at 55 miles per hour. The CB afforded people—many of whom

were distressed by recent governmental decisions—an opportunity to

create their own communities over the airwaves.

The CB, as a ‘‘voice of the people’’ and the fastest growing

communications medium since the telephone, rekindled a sense of

camaraderie during an era when people felt oppressed by a seemingly

monolithic federal government and looming corporate control. Al-

though manufacturers encouraged people to use CBs for emergency

purposes (broadcasting on channel 9) or to relieve the stress and

boredom of long automobile trips, the CB transcended these practical

functions and became a tool of empowerment, enabling each person

to be his or her own broadcaster on the 40 channels of airwaves.

Like all small communities, CB culture developed its own

language and sensibility. People liked these devices because they

could use them to evade the law by communicating with drivers up

ahead to find out the location of speed traps and police. They also

liked the CB because it allowed for mobility, anonymity, and a chance

to invent oneself. For example, instead of using proper names, CBers

(or ‘‘ratchet-jaws,’’ as users called themselves) had ‘‘handles’’—

nicknames they would use while on air. They also utilized a very

colorful vocabulary, which included words like ‘‘Smokey’’ for police

(so named because of their Smokey Bear-type hats), ‘‘Kodiaks with

CELEBRITYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

463

Kodaks’’ for police using radar, ‘‘negatory’’ for ‘‘no,’’ ‘‘10-4’’ for

message received, and ‘‘let the hammer down’’ for speeding. Broad-

cast sign-offs were equally baroque: people would not just say good-

bye, but rather phrases such as, ‘‘Keep your nose between the ditches

and the Smokeys off your britches.’’

An essential component of the growing CB popularity was the

acknowledgment and celebration of a ‘‘trucker culture,’’ summed up

by the ubiquitous phrase of the time, ‘‘Keep on Truckin’.’’ Tractor

trailer drivers had been using these radios to communicate among

themselves over the long haul for decades, and in 1973, the CB was an

integral device that enabled truckers to organize strike activities.

Soon after, ordinary people began to identify with the trucker, who

represented a freedom, heroism, and rugged individualism on the

open road. But this trucker culture was not just confined to the

roadways and airwaves. It also appeared as a recurring theme in the

popular media. ‘‘Convoy,’’ by C.W. McCall, was a novelty song

about a trucker named ‘‘Rubber Duck’’ who leads a speeding pack of

trucks across the country, avoiding police along the way; it hit number

one on the Billboard chart in 1976. ‘‘Six Days on the Road’’ was

another trucker-inspired song. The film industry also became enam-

ored of truckers and their CBs: Smokey and the Bandit, a film directed

by Hal Needham and starring Burt Reynolds and Sally Field, came

out in 1977, and in that same year Jonathan Demme directed Handle

with Care, another trucker film. In 1978 the song ‘‘Convoy’’ was

made into a film with the same title, directed by Sam Peckinpah and

starring Kris Kristofferson and Ali McGraw. And television enjoyed

BJ and the Bear during this same period.

While the American public’s love affair with the CB radio and

truckers did not last long—the glamour and glitz of the 1980s made

truckers seem backward and unhip—it did have lasting repercussions

that made people more accepting of new communications technolo-

gy. Cellular phones and the Internet were just two examples of the

continuation of the CB sensibility. Cellular phones offered a portable

means of communication that people could use in their cars for

ordinary needs and for emergencies. Internet chatrooms, while not

offering mobility, did offer a sense of anonymity and group camara-

derie and membership. The CB was the first technology that truly

offered Americans their contradictory wishes of being part of a

solidified group while their personae remained wholly anonymous if

not entirely fabricated.

—Wendy Woloson

F

URTHER READING:

Hershey, Cary, et.al. ‘‘Personal Uses of Mobile Communications:

Citizens Band Radio and the Local Community.’’ Communica-

tions for a Mobile Society: An Assessment of New Technology. Ed.

Raymond Bowers. Beverly Hills, Sage, 1978, 233-255.

Stern, Jane, and Michael Stern. Jane and Michael Stern’s Encyclope-

dia of Popular Culture. New York, HarperPerennial, 1992.

The CBS Radio Mystery Theater

Premiering on January 6, 1974, the CBS Radio Mystery Theater

was a notable attempt to revive the tradition of radio thrillers like

Suspense (1942-1962) and Inner Sanctum Mysteries (1941-52). Cre-

ated by Inner Sanctum producer Himan Brown, the CBS Radio

Mystery Theater featured many voices from the golden age of radio,

including Agnes Moorehead, Les Tremayne, Santos Ortega, Bret

Morrison, and Mercedes McCambridge. E. G. Marshall was its first

host. The series ended on December 31, 1982.

—Christian L. Pyle

Celebrity

Celebrity is the defining issue of late twentieth-century America.

In recent years, much has been made and written of the rise of

contemporary celebrity culture in the United States. Writers, thinkers,

and pundits alike warn us of the danger of our societal obsession with

celebrity, even as more and more Americans tune into Hard Copy and

buy People magazine. Andy Warhol’s cynical prediction that every-

one will be famous for fifteen minutes has virtually become a national

rallying cry as television airwaves overflow with venues for every-

one’s opportunity to appear in the spotlight. The more that is written

about fame, the less shocked we become. That’s the way things are,

we seem to say, so why not grab our moment in the sun?

Fame, of course, is nothing new. In his comprehensive volume

The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History, Leo Braudy has traced

man’s desire for recognition and need for immortality back to

Alexander the Great, noting: ‘‘In great part the history of fame is the

history of the changing ways by which individuals have sought to

bring themselves to the attention of others and, not incidentally, have

thereby gained power over them.’’ The desire to achieve recognition

is both timeless and universal. What is particular to late twentieth-

century America, however, is the democratization of fame and the

resultant ubiquity of the celebrity—a person, as Daniel Boorstin so

famously noted, ‘‘who is known for his well-knownness.’’

The origin of the unique phenomenon of twentieth-century

celebrity may be found in the words of one of America’s Founding

Fathers, John Adams, who wrote, ‘‘The rewards . . . in this life are

esteem and admiration of others—the punishments are neglect and

contempt.... The desire of the esteem of others is as real a want of

nature as hunger—and the neglect and contempt of the world as

severe as a pain.... It is the principal end of the government to

regulate this passion, which in its turn becomes the principal means of

order and subordination in society, and alone commands effectual

obedience to laws, since without it neither human reason, nor standing

armies, would ever produce that great effect.’’ Indeed, the evolution

of celebrity as the Zeitgeist of the twentieth century is a direct result

of democracy.

As Alexis De Tocqueville noted in the early 1830s, the equality

implied by a democracy creates the need for new kinds of distinction.

But there are problems inherent in this new social order, as Tocqueville

wrote: ‘‘I confess that I believe democratic society to have much less

to fear from boldness than from paltriness of aim. What frightens me

most is the danger that . . . ambition may lose both its force and its

greatness, that human passions may grow gentler and at the same time

baser, with the result that the progress of the body social may become

daily quieter and less aspiring.’’ A prescription, it would seem, for

twentieth-century celebrity. Indeed, some 150 years later, Daniel

Boorstin would describe a celebrity thus: ‘‘His qualities—or rather

his lack of qualities—illustrate our peculiar problems. He is neither

good nor bad, great nor petty.... He has been fabricated on purpose

to satisfy our exaggerated expectations of human greatness. He is

CELEBRITY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

464

morally neutral. The product of no conspiracy, of no group promoting

vice or emptiness, he is made by honest, industrious men of high

professional ethics doing their job, ‘informing’ us and educating us.

He is made by all of us who willingly read about him, who like to see

him on television, who buy recordings of his voice, and talk about him

to our friends. His relation to morality and even to reality is

highly ambiguous.’’

What Tocqueville foresaw and Boorstin confirmed in his empty

definition of celebrity seems, however, to belie the fact that, as a

nation, we have come to define success by celebrity. It is the singular

goal to which our country aspires. But how and why has this hollow

incarnation of fame become our benchmark of achievement?

The great experiment inaugurated by the signing of the Declara-

tion of Independence proposed a classless society in which the only

prerequisite for success was the desire and the will to succeed. In fact,

however, though founded on a noble premise, America was and is a

stratified society. Yet the myth of classlessness, of limitless opportu-

nity open to anyone with ambition and desire, has been so pervasive

that it has remained the unifying philosophy that drives society as a

whole. In a world where dream and reality do not always mesh, a third

entity must necessarily evolve, one which somehow links the two.

That link—the nexus between a deeply stratified society and the myth

of classlessness—is celebrity.

According to Braudy: ‘‘From the beginning, fame has required

publicity.’’ The evolution (or perhaps devolution) of fame into

celebrity in the twentieth century was the direct result of inventions

such as photography and telegraphy, which made it possible for

words and images to be conveyed across a vast nation. Abraham

Lincoln went so far as to credit his election to a photograph taken by

Matthew Brady and widely dispersed throughout his campaign.

Before the invention of photography, most Americans could have

passed a president on the street and not known it. A mania for

photography ensued and, during the nineteenth century, photograph

galleries sprang up throughout the country to satisfy the public’s

increasing hunger for and fascination with these images. The ideal

vehicle for the promulgation of democracy, photography was accessi-

ble to anyone, and thus it soon contributed to the erosion of visible

boundaries of class, even as it proclaimed a new ideal for success—

visual fame.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed an

avalanche of inventions that would transform America from a rural

country of provincial enclaves to a more unified nation of urban

centers. The rapid growth of mass media technologies spawned

increasing numbers of national publications eager to make news. And

make it they did—searching out stories that might not have been

recognized as newsworthy a decade before. As Richard Schickel

writes in Intimate Strangers: The Culture of Celebrity: ‘‘The pace of

life was quickening, the flow of information beginning to speed up

while mobility both geographic and social was stepping up as well.

People began to need familiar figures they could carry about as they

moved out and moved up, a sort of portable community as it were,

containing representations of good values, interesting traits, a certain

amount of within-bounds attractiveness, glamour, even deviltry.’’

Thus the stage was set for the invention of the motion picture.

The birth of celebrity is, of course, most closely tied to the

motion picture industry, and its embrace by a public eager to be

entertained. Paying a penny, or later a nickel, audiences from cities to

small towns could gather in a darkened movie theatre, an intimate

setting in which they could escape the reality of their daily lives and

become part of a fantasy. But how was this different from live theatre?

In part, movie houses existed all over America, and so hundreds of

thousands of people had the opportunity to see the same actor or

actress perform. Furthermore, films were churned out at a phenome-

nal rate, thus moviegoers could enjoy a particular performer in a

dozen or more pictures a year. This engendered a new kind of

identification with performers—a sense of knowing them. Addition-

ally, Schickel cites the influence of a cinematic innovation by director

D. W. Griffith: the close-up, which had ‘‘the effect of isolating the

actor in the sequence, separating him or her from the rest of the

ensemble for close individual scrutiny by the audience. To some

immeasurable degree, attention is directed away from the role being

played, the overall story being told. It is focused instead on the reality

of the individual playing the part.’’ The intimacy, immediacy, and

constancy of movies all fostered an environment ripe for celebrity.

Audiences clamored to know more about their favorite actors

and actresses, and a new kind of public personality was born—one

whose success was not measured by birth, wealth, heroism, intelli-

gence, or achievement. The fledgling movie studios quickly grasped

the power of these audiences to make or break them, and they

responded by putting together a publicity machine that would keep

the public inundated with information about their favorite performers.

From studio publicists to gossip columnists, the movie industry was

unafraid to promote itself and its product, even if it meant making

private lives totally public. But the effect was electrifying. Almost

overnight, fame had ceased to be sole property of the moneyed elite.

Movie stars, America believed, might be young, beautiful, even rich,

but otherwise they were no different from you or me. In Hollywood,

where most of the movie studios were run by Jewish immigrants,

where new stars were discovered at soda fountains, where it didn’t

matter where you came from or what your father did, anyone could

become rich or famous. This new fame carried with it the most basic

American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It

proved the system worked. Whatever the reality might be of the daily

lives of Americans, Hollywood celebrities proved that, with a lit-

tle luck, good timing, and a modicum of talent, anyone could

become somebody.

The Hollywood celebrity factory churned out stars from the very

beginning. In silent pictures, Gloria Swanson, Rudolph Valentino,

and Greta Garbo captured America’s imagination. But when sound

came to pictures, many silent stars faded into obscurity, betrayed by

squeaky voices, stutters, or Brooklyn accents. In their place were new

stars, and more of them, now that they could talk. During the Golden

Age of Hollywood, the most famous were the handsome leading men

such as Robert Taylor, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant, and beautiful

leading ladies such as Vivien Leigh, Ava Gardner, and Elizabeth

Taylor. But Hollywood had room for more than beauty—there were

dancers such as Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, singers such as Judy

Garland and Bing Crosby, funny men such as Bob Hope and Danny

Kaye, villains such as Edward G. Robinson, horror stars such as Boris

Karloff, starlets such as Betty Grable, cowboys such as Gene Autry.

The beauty of celebrity was that it seemed to have no boundaries. You

could create your own niche. As Braudy wrote: ‘‘Fame had ceased to

be the possession of particular individuals or classes and had become

instead a potential attribute of every human being that needed only to

be brought out in the open for all to applaud its presence.’’

With the invention of television, the pervasiveness and power of

celebrity grew. By bringing billions of images into America’s homes,

thousands of new faces to be ‘‘known,’’ celebrity achieved a new

intimacy. And with the decline of the studio system, movie stars

began to seem more and more like ‘‘regular people.’’ If the stars of the

CELEBRITY CARICATUREENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

465

Golden Age of Hollywood had been America’s ‘‘royalty,’’ now no

such pretensions existed. From the mumbling Marlon Brando to the

toothy Tom Cruise, the stars of the new Hollywood seemed to expand

the promise of celebrity to include everyone.

Celebrity, of course, did not remain the sole property of Holly-

wood. During the Roaring Twenties, Americans experienced a period

of prosperity unlike any that had existed in the nation’s 150-year

history. With new wealth and new leisure time, Americans not only

flocked to the movies, they went to baseball games and boxing

matches, and there they found new heroes. Babe Ruth became an icon

whose extraordinary popularity would pave the way for such future

superstars as Joe DiMaggio and Michael Jordan. During the 1920s,

however, Ruth’s popularity would be rivaled by only one other man, a

hero from a new field—aviation. When Charles Lindbergh became

the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, he was hailed as

a national savior. America’s hunger for celebrity seemed unquenchable

as each new star seemed a new fulfillment of a country’s promise, of

the American Dream.

The history of the twentieth century is the history of the growing

influence of celebrity. No area of American society has remained

untouched. The entertainment industry is no longer confined to

Hollywood. Sports, music, art, literature, and even politics have

embraced the celebrity ethos in order to succeed. It has been said that

if Franklin Delano Roosevelt—a man in a wheelchair—were to run

for president today, he would not be elected. We live in a society

bounded and defined by the power of images, by the rules of celebrity.

Dwight D. Eisenhower hired former matinee idol Robert Montgom-

ery to be his consultant on television and media presentations. John F.

Kennedy, an Irish Catholic, won the presidency because he looked

like a movie star and he knew how to use the media, unlike Richard

Nixon, who dripped with sweat and seemed uncomfortable on cam-

era. Ronald Reagan, a former actor with little political ability, used his

extensive media savvy to become a two-term president. Today, a

politician cannot even be considered a presidential hopeful unless he

has what it takes to be a celebrity. Visual appearance and the ability to

manipulate the press are essential to becoming our chief of state,

political knowledge and leadership come second.

Yet the more pervasive celebrity has become, the more it is

decried, particularly by celebrities themselves, who claim that they

have been stripped of their privacy. As Braudy describes this paradox:

‘‘Fame is desired because it is the ultimate justification, yet it is hated

because it brings with it unwanted focus as well, depersonalizing as

much as individualizing.’’ The greater the need for audience approv-

al, the more powerful the audience—and thus the media—has be-

come. With the death of Princess Diana, an outcry for privacy was

heard from the celebrity community and blame was cast on the media,

even as hundreds of thousands of people poured into London to pay

tribute to the ‘‘People’s Princess’’ and millions mourned her death on

television around the globe. Celebrity’s snare is subtle—even as the

public itself vilifies the press, it craves more. And even as celebrities

seek to put limits on their responsibilities to their audience, they are,

in fact, public servants.

By the late twentieth century, celebrity has become so ubiqui-

tous that visibility has become a goal in itself. Tocqueville’s predic-

tion has come true. Americans no longer seem to aspire to greatness.

They aspire to be seen. John Lahr wrote: ‘‘The famous, who make a

myth of accomplishment, become pseudo-events, turning the public

gaze from the real to the ideal.... Fame is America’s Faustian

bargain: a passport to the good life which trivializes human endeav-

or.’’ But despite the deleterious effects of celebrity, it continues to

define the American social order. After all, as Mae West once said,

‘‘It is better to be looked over than overlooked.’’

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Boorstin, Daniel. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America.

New York, Vantage Books, 1987.

Braudy, Leo. The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History. New

York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1986.

Brownstein, Ronald. The Power and the Glitter: The Hollywood-

Washington Connection. New York, Pantheon Books, 1990.

De Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. J. P. Mayer, editor.

New York, Harper Perennial, 1988.

Gabler, Neal. Walter Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of

Celebrity. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Gamson, Joshua. Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary Ameri-

ca. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994.

Lahr, John. ‘‘Notes on Fame.’’ Harper’s. January 1978, 77-80.

Schickel, Richard. Intimate Strangers: The Culture of Celebrity.

Garden City, Doubleday, 1985.

Celebrity Caricature

Celebrity caricature in America has become a popular twentieth-

century permutation of the longstanding art of caricature—the distor-

tion of the face or figure for satiric purposes—which claims an

extensive tradition in Western art. For centuries, comically exaggerat-

ed portrayals have served the purpose of ridicule and protest, probing

beneath outward appearances to expose hidden, disreputable charac-

ter traits. In the early twentieth century, however, American caricaturists

based in New York City deployed a fresh approach, inventing a new

form of popular portraiture. They chose for their subjects the colorful

rather than the corrupt personalities of the day, reflecting the preoccu-

pation with mass media-generated fame. During the height of its

vogue between the two World Wars, celebrity caricature permeated

the press, leaving the confines of the editorial cartoon to flourish on

the newspaper’s entertainment pages, at the head of a syndicated

column, on a magazine cover, or color frontispiece. Distorted faces

appeared on café walls, silk dresses, and cigarette cases; Ralph

Barton’s caricature theater curtain depicting a first-night audience

caused a sensation in 1922. Caricaturists did not attempt to editorial-

ize or criticize in such images. ‘‘It is not the caricaturist’s business to

be penetrating,’’ Barton insisted, ‘‘it is his job to put down the figure a

man cuts before his fellows in his attempt to conceal the writhings of

his soul.’’ These artists highlighted the public persona rather than

probing beneath it, reconstructing its exaggerated components with a

heightened sense of style and wit. Mocking the celebrity system,

caricature provided a counterbalance to unrestrained publicity.

American caricaturists sought a modern look, derived from

European art, to express a contemporary urbanity. They departed

from comic conventions, selectively borrowing from the radical art

movements of the day. Like advertisers, they began to simplify,

elongate, geometricize, and fragment their figural forms. Eventually,

CELEBRITY CARICATURE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

466

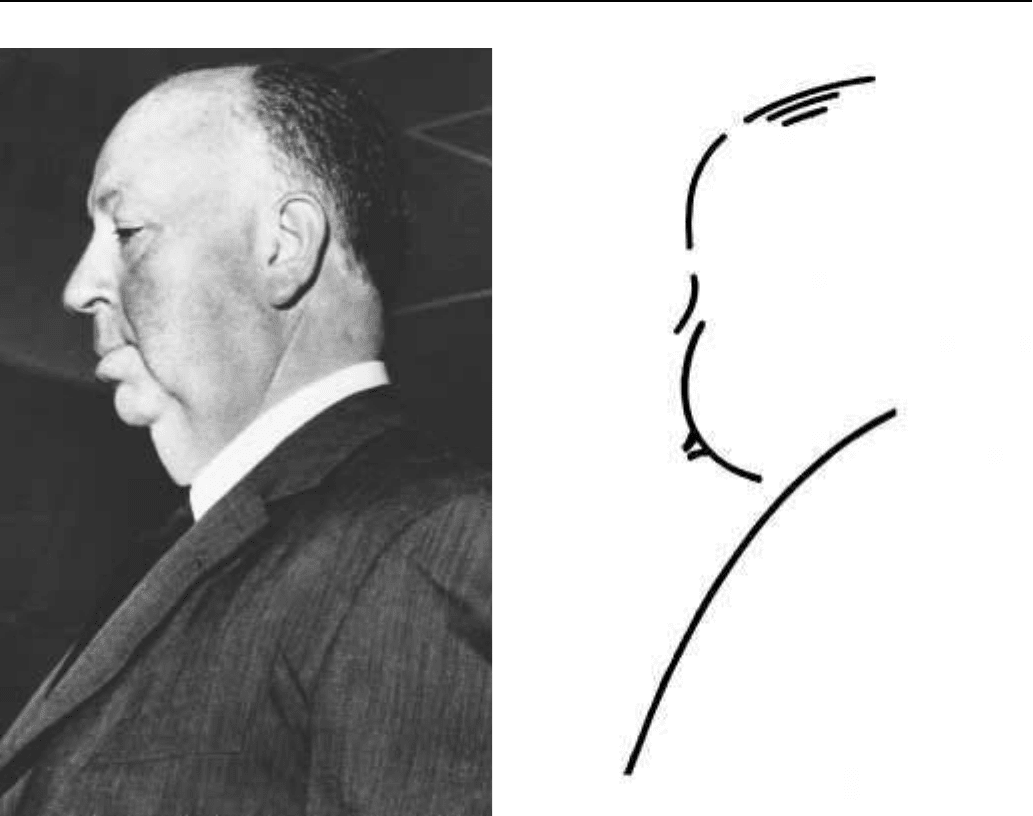

Alfred Hitchcock in profile.

their stylish mockery would be fueled by the abstractions, collage

techniques, color dissonances, and unexpected conflations of Cub-

ism, Fauvism, and Surrealism. Humor and a recognizable face made

modernist stylization palatable. Artist and critic Carlo de Fornaro,

arriving in New York around 1898, was the first to advocate a Parisian

style of caricature that was closely related to French poster art. His

india ink newspaper caricatures combined an art nouveau elongation

of the figure with a bold simplification of form. Caricaturist Al Frueh

abbreviated images of theatrical figures into quintessential summa-

ries of their characteristics. Critics marveled at Frueh’s ability to

evoke a personality with a minimum of lines, and Alfred Stieglitz, the

acknowledged ringleader of the New York avant-garde before World

War I, exhibited his drawings in 1912.

Mexican-born artist Marius de Zayas’s approach to caricature

especially intrigued Stieglitz, who mounted three exhibitions of his

work. De Zayas drew dark, atmospheric charcoal portraits suggestive

of pictorialist photographs and enigmatic symbolist drawings. Influ-

enced by Picasso, he even experimented with ‘‘abstract caricature,’’ a

radical departure from visual realism. Many critics admired the

aesthetic sophistication of this updated art form. ‘‘Between mod-

ern caricature and modern ‘straight’ portraiture,’’ the New York

A caricature of Alfred Hitchcock in profile.

World’s Henry Tyrrell wrote, ‘‘there is only a thin and vague line

of demarcation.’’

Ties to the avant-garde raised the prestige of caricature and

encouraged its use in such ‘‘smart’’ magazines of the post war era as

Life, Judge, Vanity Fair, and the New Yorker. Caricature reflected a

new strain of light, irreverent parody that pervaded the Broadway

stage, the vaudeville circuit, Tin Pan Alley, magazine verses, newspa-

per columns, and the writings of the Algonquin Round Table wits. In

the early 1920s, Vanity Fair, a leading proponent of this art, recruited

the young Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias to draw portraits of café

society luminaries. His powerful ink line lent an iconic, monumental

quality to his figures. ‘‘They are bald and crude and devoid of

nonsense,’’ Ralph Barton wrote, ‘‘like a mountain or a baby.’’

Advances in color printing gave caricature an additional appeal in the

1930s. Will Cotton provided portraits in bright pastels, employing

color as a comic weapon. Artist Paolo Garretto used collage, airbrushed

gouache, and a crisp Art Deco stylization to create vivid visual effects.

The best artists in the increasingly crowded field honed their

clever deformations with a distinctive style. William Auerbach-Levy

eliminated details and distilled shapes into logo-like faces that were

printed on stationery and book jackets. Covarrubias, working in

CEMETERIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

467

watercolor, lampooned the leveling nature of celebrity. Visual con-

trasts of such opposite personalities as Martha Graham and fan dancer

Sally Rand, in his famous ‘‘Impossible Interviews’’ series, were

undermined by the commonality of fame. Few could evoke the

dynamic movement of performance as well as Al Hirschfeld, whose

swooping curves and sharp angles captured in mid-step the familiar

look of a dancer or actor.

Caricature exploited the appetite for modern celebrity whetted

by the developing mass media. The nature of fame had changed, and

notability was no longer tied to traditional areas of accomplishment.

As Vanity Fair explained, caricature subjects were selected ‘‘because

of their great interest as personalities.’’ Information about the famous

became increasingly standardized: publicity photographs, syndicated

stories, records, films, and news clips consolidated the celebrity

image. Caricature consistently reflected the narrow, shallow exag-

gerations that the mass media dispensed. The famous learned to

appreciate the compliment. H.L. Mencken wrote to one artist that he

liked his caricature: ‘‘It is grotesque and yet it does justice to my

underlying beauty.’’ Emily Post, unflatteringly portrayed in a maga-

zine, thanked the editor for the ‘‘delicious publicity.’’

The celebrity caricature fad peaked in the 1920s and 1930s. The

trend even inspired star-studded animated cartoons, and collectible

dolls, masks, and puppets of film idols. By mid-century, it was on the

wane. The Depression years and advent of World War II demanded

sharper satiric voices. And, although magazines of the 1940s still

published caricature, editors turned increasingly to photography.

Influenced by changes in art, humor, literature, and fame in an age of

television, caricature evolved into new forms and specialized niches.

In its heyday, caricature helped people adapt to change, alleviating the

shock of modern art, leveling high and low cultural disparities, and

mocking the new celebrity industry. Furthermore, in the celebrity-

crazed press of the late twentieth century, witty, personality-based

celebrity caricature seemed to be making a come-back.

—Wendy Wick Reaves

F

URTHER READING:

Auerbach-Levy, William. Is That Me? A Book about Caricature.

New York, Watson-Guptill, 1947.

Barton, Ralph. ‘‘It Is to Laugh.’’ New York Herald Tribune. October

25, 1925.

Bruhn, Thomas P. The Art of Al Frueh. Storrs, Connecticut, William

Benton Museum of Art, 1983.

Hirschfeld, Al. The World of Hirschfeld. New York, Harry

Abrams, 1970.

Hyland, Douglas. Marius de Zayas: Conjuror of Souls. Lawrence,

Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1981.

Kellner, Bruce. The Last Dandy: Ralph Barton, American Artist,

1891-1931. Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1991.

Reaves, Wendy Wick. Celebrity Caricature in America. New Haven,

Yale University Press, 1998.

Reilly, Bernard F., Jr. ‘‘Miguel Covarrubias: An Introduction to His

Caricatures.’’ In Miguel Covarrubias Caricatures. Washington,

D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985, 23-38.

Updike, John. ‘‘A Critic at Large: A Case of Melancholia.’’ New

Yorker. February 20, 1989, 112-120.

Williams, Adriana. Covarrubias. Austin, University of Texas

Press, 1994.

Wright, Willard Huntington. ‘‘America and Caricature.’’ Vanity

Fair. July 1922, 54-55.

Cemeteries

Cemeteries reflect society’s interpretation of the continuing

personhood of the dead. Colonial America’s small rural family

graveyards and churchyard burial grounds were an integral part of the

community of the living, crowded with tombstones bearing the

picturesque iconography of winged skulls, hourglasses, and soul-

effigies, and inscriptions ranging from the taciturn to the talkative—

some with scant facts of name, age, and date of death, others offering

thumbnail biographies, unusual circumstances of decease (‘‘They

froze to death returning from a visit’’), homilies in verse (‘‘As I am

now, so you shall be, / Remember death and follow me’’), and even

the occasional dry one-liner (‘‘I expected this, but not so soon’’).

In the nineteenth century, alarmed by public health problems

associated with increasing industrial urbanization, the rising medical

profession pressed for new cemeteries on the outskirts of towns,

where the buried bodies could not pollute nearby wells and where any

‘‘noxious exhalations’’ thought to cause disease would be dissipated

in the fresh suburban air. These new ‘‘garden cemeteries’’ would also

function as places to which the inhabitants of the teeming cities could

go for recreation and the inspiration of the beauty of nature.

First of the new genre was Mount Auburn Cemetery, picturesquely

sited on a bend in the Charles River between the cities of Boston and

Cambridge. Three years in the making, with carriage paths and artful

landscaping (thanks to the collaboration of the Massachusetts Horti-

cultural Society), it opened in 1831 to enthusiastic reviews and was

soon followed by Mount Hope in Bangor, Maine; Laurel Hill in

Philadelphia; Spring Grove in Cincinnati; Graceland in Chicago;

Allegheny County Cemetery in Pittsburgh; and the battlefield burial

ground at Gettysburg. By the end of the 1800s there were nearly two

hundred garden cemeteries in America.

The boom in street-railway construction in the 1870s made the

outlying cemeteries readily accessible to the public for day-trips and

picnics. In several cities the departed could ride the rails to the

cemetery, too. (The United Railways and Electric Company of

Baltimore owned the ‘‘Dolores,’’ a funeral car with seats for thirty-

two plus a compartment for the casket. Philadelphia had a streetcar

hearse as well, the ‘‘Hillside.’’) But the streetcar revolution also

fueled suburban development of the open spaces surrounding the

cities of the dead, even as parks for the living began to compete for the

shrinking acreage of undeveloped land. (Frederick Law Olmsted,

while designing New York’s Central Park, completed just after the

Civil War, is reported to have said: ‘‘They’re not going to bury

anyone in this one.’’)

With the passing of the Victorian age and the splitting off of

parks from cemeteries, cemetery management began to stress effi-

ciency and profitability. A pioneer of this new approach was Dr.

Hubert Eaton, a former mine owner who bought a down-at-heels

graveyard called Forest Lawn in Glendale, California, in 1917, and

over the next four decades metamorphosed it into a flagship of

twentieth-century cemetery design and culture with hundreds of miles

of underground piping for sprinklers and flat bronze markers in place

of headstones (allowing the trimming of vast areas by rotary-blade

CENTRAL PARK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

468

machines and of maintenance costs by as much as 75 percent). Area

themes included ‘‘Babyland’’ and ‘‘Wee Kirk o’ the Heather,’’

accented by sculptures such as Duck Frog and the occasional

classical reproduction.

While not every memorial park could aspire to be a Forest Lawn,

by the end of World War II, private cemetery management had

become a thriving industry with its own trade journals—such as

American Cemetery, Cemeterian, and Concept: The Journal of Crea-

tive Ideas for Cemeteries—and a ready target for both the biting satire

of Evelyn Waugh’s 1948 novel The Loved One and the merciless

investigative reporting of Jessica Mitford’s 1963 exposé, The Ameri-

can Way of Death.

Attitudes toward death itself were changing as well. The

medicalization of dying, with its removal from home to hospital,

helped to transform the awe-inspiring last event of the human life

cycle into a brutal, even trivial fact. Whether from denial or mere

pragmatism, two-thirds of the students polled at three universities

said they would favor cremation, while a rise in the number of

anatomical donors prompted medical schools in the greater Boston

area to begin sharing excess cadavers with one another whenever one

school had a surplus.

Public policy also took an increasingly utilitarian tack. In 1972,

ninety years after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the nonprofit status

of cemeteries owing to their ‘‘pious and public purpose,’’ the Depart-

ment of Housing and Urban Development declared that burial was a

marginal land use and proposed establishing cemeteries under elevat-

ed highways, in former city-dump landfills, or on acreage subject to

airport runway noise.

‘‘After thirty years a grave gets cold,’’ one mausoleum builder

ruefully told cemetery historian Kenneth T. Jackson, who noted the

high mobility of Americans near the end of the twentieth century and

the fact that older cemeteries ‘‘run out of space, and few people still

alive remember anyone buried there.’’ As individual markers and

statuary fell into disrepair or were vandalized, indifferently main-

tained graveyards became less and less attractive places—ironically

turning again into recreational areas, but now for persons and activi-

ties unwelcome in the public parks.

Notable exceptions to this trend are sites where the famous are

buried, such as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and of President

Kennedy in Arlington National Cemetery, or Elvis Presley’s grave

site at his Graceland mansion in Memphis, which continue to draw

thousands of pilgrims every year.

—Nick Humez

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Francis D., compiler. Documents and Facts, Showing the Fatal

Effects of Interment in Populous Cities. New York, F. D. Al-

len, 1822.

Drewes, Donald W. Cemetery Land Planning. Pittsburgh, Matthews

Memorial Bronze, 1964.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Silent Cities: The Evolution of the American

Cemetery. New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 1989.

Klupar, G. J. Modern Cemetery Management. Hillside, Catholic

Cemeteries of the Archdiocese of Chicago, 1962.

Linden-Ward, Blanche. Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory

and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. Columbus, Ohio State

University Press, 1989.

Miller, John Anderson. Fares, Please! A Popular History of Trolleys,

Horsecars, Streetcars, Buses, Elevateds, and Subways. New York,

Dover, 1960.

Mitford, Jessica. The American Way of Death. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1963.

Shomon, Joseph James. Crosses in the Wind. New York, Stratford

House, 1947.

Waugh, Evelyn. The Loved One. Boston, Little, Brown and Compa-

ny, 1948.

Weed, Howard Evarts. Modern Park Cemeteries. Chicago, R. J.

Haight, 1912.

Central Park

The first major public example of landscape architecture, Man-

hattan’s Central Park remains the greatest illustration of the American

park, a tradition that would become part of nearly every community

following the 1860s. This grand park offers a facility for recreation

and peaceful contemplation, a solution to the enduring American

search for a ‘‘happy medium’’ between the natural environment and

human civilization.

Initially, the construction of parks responded to utilitarian im-

pulses: feelings began to develop in the early 1800s that some urban

areas were becoming difficult places in which to reside. Disease and

grime were common attributes attached to large towns and cities. Of

particular concern, many population centers possessed insufficient

interment facilities within churchyards. The first drive for parks

began with this need for new cemeteries. The ‘‘rural cemetery’’

movement began in 1831 with the construction of Mount Auburn

outside of Boston. Soon, many communities possessed their own

sprawling, green burial areas on the outskirts of town.

From this point, a new breed of American landscape architect

beat the path toward Central Park. Andrew Jackson Downing de-

signed many rural cemeteries, but more importantly, he popularized

and disseminated a new American ‘‘taste’’ that placed manicured

landscapes around the finest homes. Based out of the Hudson River

region and operating among its affluent landowners, Downing de-

signed landscapes that brought the aesthetic of the rural cemetery to

the wealthy home. His designs inspired the suburban revolution in

American living. Downing became a public figure prior to his

untimely death in 1852 through the publication of Horticulturalist

magazine as well as various books, the initial designs for the Mall in

Washington, D.C., and, finally, his call for a central area of repose in

the growing city on Manhattan Island.

Wealthy New Yorkers soon seized Downing’s call for a ‘‘central

park.’’ This landscaped, public park would offer their own families an

attractive setting for carriage rides and provide working-class New

Yorkers with a healthy alternative to the saloon. After three years of

debate over the park site and cost, the state legislature authorized the

city to acquire land for a park in 1853. Swamps and bluffs punctuated

by rocky outcroppings made the land between 5th and 8th avenues

and 59th and 106th streets undesirable for private development. The

extension of the boundaries to 110th Street in 1863 brought the park to

its current 843 acres. However, the selected area was not empty: 1,600

poor residents, including Irish pig farmers and German gardeners,

lived in shanties on the site; Seneca Village, at 8th Avenue and 82nd