Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CENTRAL PARKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

469

A view of New York’s Central Park.

Street, was one of the city’s most stable African-American settle-

ments, with three churches and a school.

In 1857, the Central Park Commission held the country’s first

landscape design contest and selected the ‘‘Greensward Plan,’’

submitted by Frederick Law Olmsted, the park’s superintendent at the

time, and Calvert Vaux, an English-born architect and former partner

of Downing. The designers sought to create a pastoral landscape in

the English romantic style. In order to maintain a feeling of uninter-

rupted expanse, Olmsted and Vaux sank four transverse roads eight

feet below the park’s surface to carry cross-town traffic. From its

inception, the site was intended as a middle ground that would allow

the city’s life to continue uninterrupted without infringing on the

experience of park goers.

The park quickly became a national phenomenon. First opened

for public use in the winter of 1859 when thousands of New Yorkers

skated on lakes constructed on the site of former swamps, Central

Park opened officially in 1863. By 1865, the park received more than

seven million visitors a year. The city’s wealthiest citizens turned out

daily for elaborate late-afternoon carriage parades. Indeed, in the

park’s first decade more than half of its visitors arrived in carriages,

costly vehicles that fewer than five percent of the city’s residents

could afford. Olmsted had stated his intention as ‘‘democratic recrea-

tion,’’ a park accessible to everyone. There would be no gates or

physical barriers; however, there would be other methods of enforc-

ing class selectivity. Stringent rules governed early use of the ‘‘demo-

cratic’’ park, including a ban on group picnics—which discouraged

many German and Irish New Yorkers; a ban on small tradesmen using

their commercial wagons for family drives in the park; and restricting

ball playing in the meadows to school boys with a note from their

principal. New Yorkers repeatedly contested these rules, however,

and in the last third of the nineteenth century the park opened up to

more democratic use.

Central Park’s success fueled other communities to action.

Olmsted became the park movement’s leader as he tied such facilities

to Americans’ ‘‘psychological and physical health.’’ Through

Olmsted’s influence and published writing, parks such as Central

Park were seen to possess more than aesthetic value. The idea of

determining the ‘‘health’’ of the community through its physical

design was an early example of modernist impulses. However, the

park movement’s attachment to traditions such as romanticism gave

parks a classical ornamentation. Olmsted’s park planning would lead

to the ‘‘City Beautiful’’ movement in the early 1900s and to the

establishment of the National Park system.

As the uses of Central Park have varied, its popularity has only

increased. In the 1960s, Mayor John Lindsay’s commissioners wel-

comed ‘‘happenings,’’ rock concerts, and be-ins to the park, making it

CENTURY 21 EXPOSITION ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

470

a symbol of both urban revival and the counterculture. A decline in

the park’s upkeep during the 1970s stimulated the establishment of

the Central Park Conservancy in 1980. This private fund-raising body

took charge of restoring features of the Greensward Plan. By 1990,

the Central Park Conservancy had contributed more than half the

public park’s budget and exercised substantial influence on decisions

about its future. Central Park, however, continues to be shaped by the

public that uses it: joggers, disco roller skaters, softball leagues, bird

watchers, nature lovers, middle-class professionals pushing a baby’s

stroller, impoverished individuals searching for an open place to sleep.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Blackmar, Elizabeth, and Roy Rosenzweig. The Park and the People.

New York, Henry Holt, 1992.

Schuyler, David. Apostle of Taste. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1996.

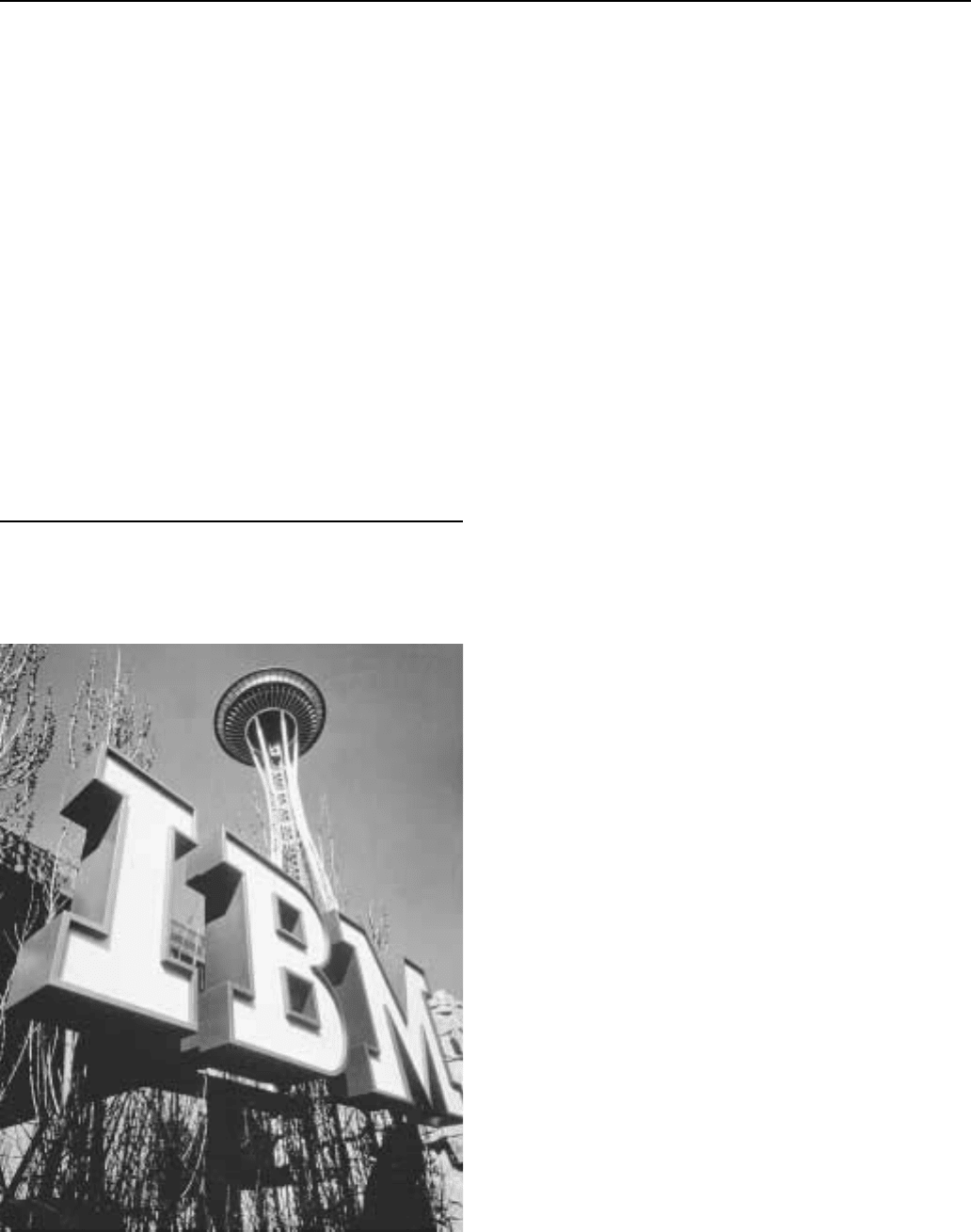

Century 21 Exposition (Seattle, 1962)

The world’s fair that opened in Seattle on April 21, 1962, better

known as the Century 21 Exposition, was one of the most successful

world’s fairs in history. Originally intended to commemorate the 50th

The dramatic symbol of the Century 21 Exposition, a 600 foot Space

Needle in Seattle, Washington.

anniversary of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held in Seattle in

1909, Century 21, although opening three years late, was still a boon

to the city itself and to the entire Northwest region of the United States.

Joseph Gandy and Ewen Dingwall started organizing the fair in

1955, but their efforts were thwarted by both potential investors and

citizens of Seattle, who worried about the profitability of a fair held in

such a far-away location and the effects it would have on the local

area. Compared to other fairs, the Century 21 project seemed dubious

at best. The 1958 Brussels Fair covered 550 acres, while the Century

21 was only 74 acres: boosters called it the ‘‘jewel box fair,’’ while

critics dubbed it the ‘‘postage stamp fair.’’ Others worried that Seattle

would not draw masses of tourists to its relatively remote region,

especially since New York was hosting its own world’s fair only a

year later.

Ultimately, however, Century 21 proved to be financially and

culturally successful. While the New York World’s Fair of 1963-

1964 lost $18 million, Century 21 actually turned a profit of $1

million after all expenses were paid—an almost unheard of feat when

it came to such endeavors. During its six month run, the fair hosted

over 10 million visitors from the United States and overseas. News of

the fair appeared in the popular press, including newspapers like the

New York Times and magazines like Newsweek, Time, Popular

Mechanics, and Architectural Review. This mass of publicity and the

increase in tourism transformed Seattle from a minor, provincial city

into an energetic metropolis that garnered respect even among its east

coast rivals.

In addition to improving its reputation, Century 21 also changed

the physical space of Seattle. The fair was held just north of the center

of the city, creating an entirely new complex, Seattle Center, that

remained long after the fair had closed. The physical structures of the

fair also changed Seattle’s skyline with the addition of the Monorail

and the Space Needle.

The theme of Century 21 was ‘‘life in the twenty-first century,’’

which meant that the fair itself, at which 49 countries participated,

celebrated scientific developments, technology, and visions of pro-

jected life in the next century. For example, the United States Science

Pavilion, designed by Seattle-born architect Minoru Yamasaki, cov-

ered seven acres, consisted of six buildings which incorporated

courtyards and pools, and featured five tall white slender aluminum

gothic arches that signified the future more than recalling the past.

This building became the Pacific Science Center after the fair.

The Monorail was an even more successful representation of the

future, and was an important component of the fair both in presence

and function. An elevated version of a subway employed to alleviate

parking problems, the Monorail demonstrated a futuristic mode of

urban transportation at work that took people from downtown Seattle

into the middle of the fair. Designed by the Swedish firm Alweg and

built in West Germany, the Monorail was capable of going 70 miles

per hour, although it never reached this speed while in use at the fair.

The most visible symbol of the fair and of the future, however,

was the Space Needle—a 600 feet high spire of steel topped with what

resembled a flying saucer; during the fair, the Space Needle netted

$15,000 a day from visitors who paid to ride its elevators up to the top

to view the greater Seattle area and to eat in its revolving restaurant.

Influenced by the design of a television tower in Stuttgart, but also

incorporating the decade’s aesthetic of the future—flattened disks

juxtaposed with pointed shapes—the Space Needle became the

Exposition’s main icon, signifying ‘‘soaring and aspiration and

progress’’ according to one of its proponents. It remained an integral

part of Seattle’s identity, permanently affixed to its skyline, and

CENTURY OF PROGRESSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

471

represented both the city itself and the subsequently outdated 1960s

vision and version of the future.

—Wendy Woloson

F

URTHER READING:

Allwood, John. The Great Exhibitions. London, Studio Vista, 1977.

Berklow, Gary M. ‘‘Seattle’s Century 21, 1962.’’ Pacific Northwest

Forum. Vol. 7, No. 1, 1994, 68-80.

Morgan, Murray. The Story of the Seattle World’s Fair, 1962. Seattle,

Acme Press, 1963.

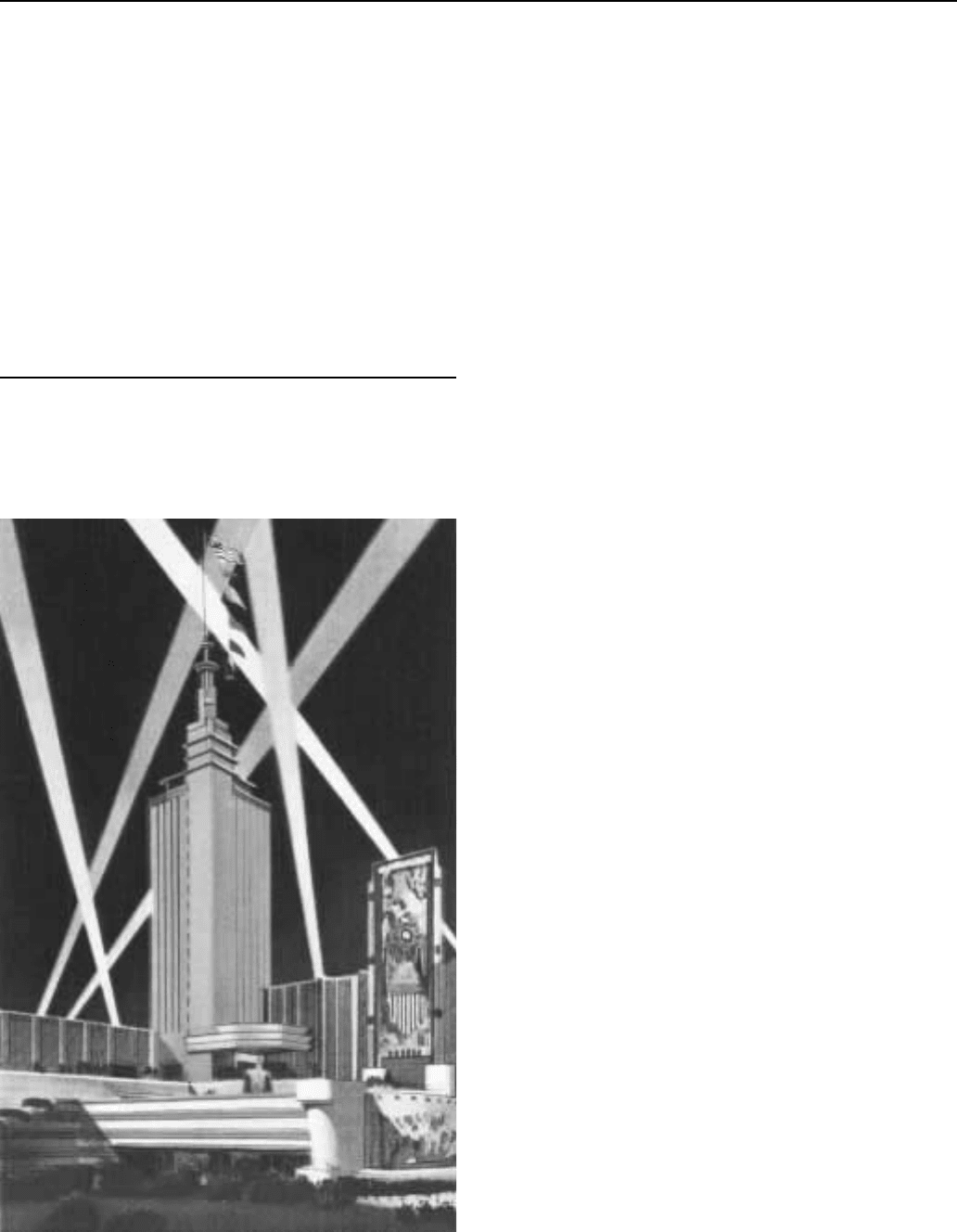

Century of Progress (Chicago, 1933)

Taking place during a ‘‘golden age’’ of world’s fairs, Chicago’s

1933-34 Century of Progress International Exposition marked the

prevalence of modern architecture and was notable for its colorful

nighttime lighting. Century of Progress commemorated the one

The Hall of Science at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

hundredth anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Chicago

with exhibits highlighting scientific discoveries and the changes these

discoveries made in industry and everyday life.

The fair opened on May 27, 1933, when the lights were turned on

with energy from the rays of the star Arcturus. The rays were focused

on photoelectric cells in a series of astronomical observatories and

then transformed into electrical energy which was transmitted to

Chicago. Under the direction of general manager Lenox R. Lohr and

president of the Board of Trustees Rufus C. Dawes, the fair covered

427 acres (much of it landfill) on Lake Michigan immediately south

of Chicago’s downtown area, from 12th Street to 39th Street (now

Pershing Road). Today, Meigs Field and McCormick Place occupy

this site. Originally planned to close in November 1933, the fair was

extended through 1934 because of its popularity and to earn enough

money to cover its debts. Century of Progress was the first interna-

tional fair in American history to pay for itself. The grand total of

attendance was 48,769,227.

The fair’s most recognizable buildings, the Hall of Science and

the Transportation Building typified the linear, geometric Art Deco

style which was the trademark of this world’s fair. The outstanding

feature of the Transportation Building was its domed roof, suspended

on cables attached to twelve steel towers around the exterior. Also

notable were the pavilions of General Motors, Chrysler, and, added in

1934, the Ford Motor Company. The House of Tomorrow was

designed using technologically advanced concepts like electrically

controlled doors and air that recirculated every ten minutes. The

controversial ‘‘Rainbow City’’ color scheme of Century of Progress

dictated that buildings be painted in four hues from a total of twenty-

three colors. Although the colors were restricted to ten in 1934, this

still was quite a contrast from the World’s Columbian Exposition held

in Chicago in 1893 when all the buildings were white. At night, the

Century of Progress buildings were illuminated with white and

colored lights which made the effect even more vibrant. In 1934, the

coordination of color schemes throughout the fairground helped

people make their way through the grounds.

The Midway, with its rides and attractions, was one of the most

popular places at the fair, as was Enchanted Island, an area set aside

for children. Youngsters could slide down Magic Mountain, view a

fairy castle, or see a play staged by the Junior League of Chicago. The

Belgian Village, which many exhibiting countries imitated during the

second year of the fair, was a copy of a sixteenth-century village

complete with homes, shops, church, and town hall. The Paris

exhibition included French restaurants, strolling artists, and an ‘‘Eng-

lish Village.’’ The Sky Ride, a major landmark of Century of

Progress, transported visitors 218 feet above the North Lagoon in

enclosed cars supported between two 628-foot steel towers. Re-

creations of the cabin of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the first

permanent settler of Chicago, and Fort Dearborn, built in 1803,

depicted Chicago-area history where Michigan Avenue crosses the

Chicago River in present-day downtown Chicago.

Although three buildings (the Administration Building, the Fort

Dearborn replica, and the golden Temple of Jehol) were temporarily

left intact after the fair’s demolition, today only Balbo’s Column

remains on its original site east of Lake Shore Drive at 1600 South

(opposite Soldier Field). A gift of the Italian government, this column

was removed from the ruins of a Roman temple in Ostia. It com-

memorates General Balbo’s trans-Atlantic flight to Chicago in 1933.

—Anna Notaro

CHALLENGER DISASTER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

472

FURTHER READING:

A Century of Progress Exposition Chicago 1933. B. Klein Publica-

tions, 1993.

Findling, John E. and Kohn E. Findling. Chicago’s Great World’s

Fairs (Studies in Design and Material Culture). Manchester,

Manchester University Press, 1995.

Linn, James Weber. The Official Pictures of a Century of Progress

Exposition Chicago 1933. B. Klein Publications, 1993.

Rossen, Howard M. World’s Fair Collectibles: Chicago, 1933 and

New York, 1939. Schiffer Publishing, 1998.

Challenger Disaster

The explosion of NASA space shuttle Challenger shortly after

liftoff on January 28, 1986, shocked the nation. The twenty-fifth

shuttle flight had been dubbed the ‘‘Teacher in Space’’ mission; the

plan was to excite children about the possiblity of space travel by

having a teacher deliver televised lectures from the orbiting shuttle.

Christa McAuliffe, a high-school social studies teacher, was chosen

for the expedition after a highly publicized nationwide search. Other

crew members included Michael Smith (pilot), Dick Scobee (com-

mander), Judith Resnik (mission specialist), Ronald McNair (mission

specialist), Ellison Onizuka (mission specialist), and Gregory Jarvis

(payload specialist). None survived the disaster. The cause of the

explosion was eventually traced to faulty gaskets known as O-rings.

Coming at a time when the United States space program had seeming-

ly regained its footing after two decades of decline, it forced many to

grapple with the risks associated with pioneering technologies. No-

where was the need for explanation more pressing than in the nation’s

classrooms, where children had gathered to witness the wonders of

space travel.

—Daniel Bernardi

F

URTHER READING:

Coote, Rodgers. Air Disasters. New York, Thomson Learning, 1993.

Penley, Constance. NASA/Trek: Popular Science and Sex in America.

New York, Verso, 1997.

‘‘51-L (25).’’ http://www.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-l/mis-

sion-51-l.html. January 1999.

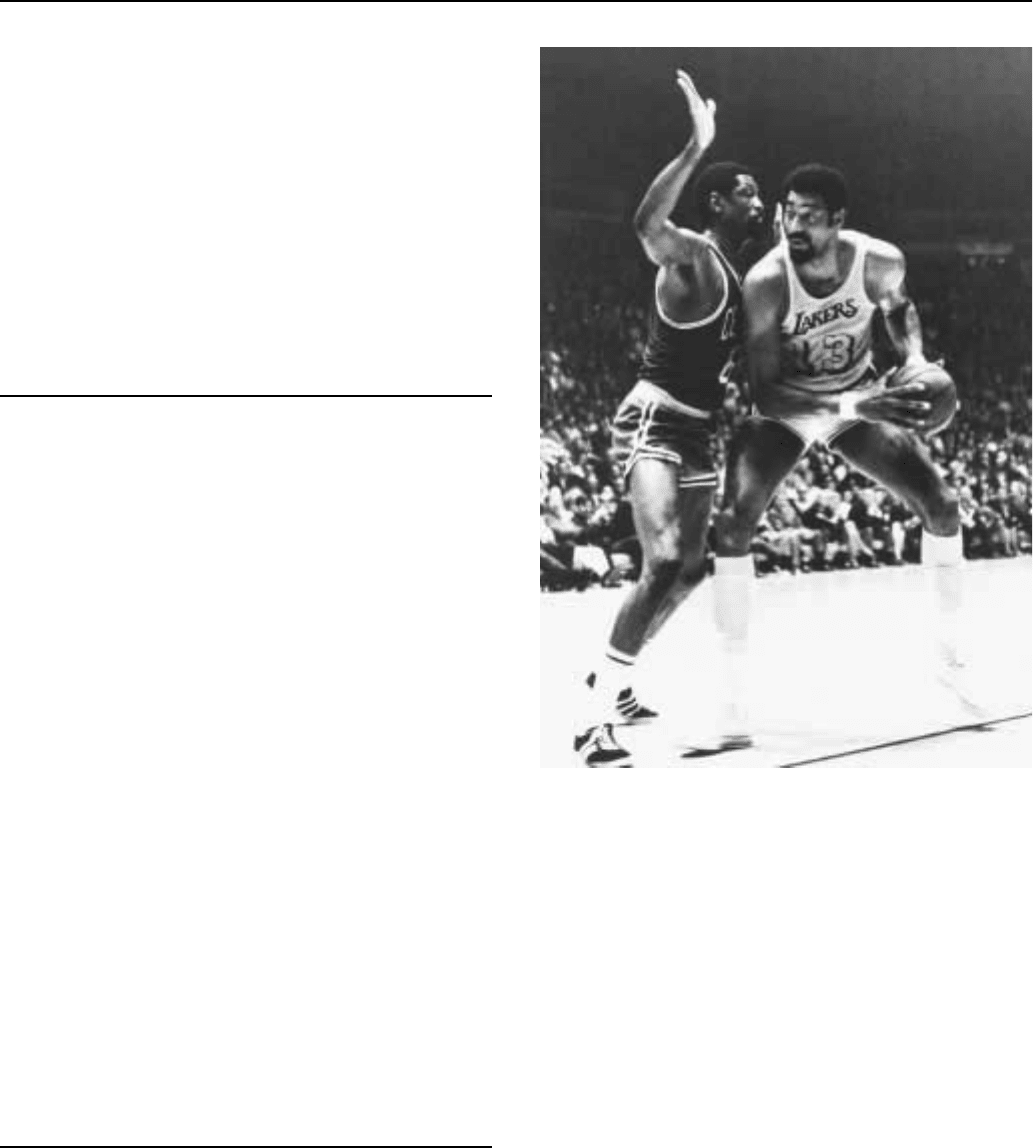

Chamberlain, Wilt (1936—)

On the basketball court, Wilt Chamberlain was one of the most

dominating players of his day. His intimidating stature (7’ 1’’ and 265

pounds) and his ability to score at will made him one of professional

basketball’s most popular players. In his third season he led the league

with a remarkable 50.4 scoring average, a record that still stands after

nearly forty years. By dominating both ends of the court Chamberlain

single-handedly revolutionized professional basketball.

Born on August 21, 1936, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cham-

berlain attended Overbrook high school, where he led his team to a

Los Angeles Laker center Wilt Chamberlain is defended by Bill Russell of

the Boston Celtics.

58-3 record and three All-Public school titles. His dominating athleti-

cism at Overbrook drew the attention of nearly every college basket-

ball program in the country, and after a hectic recruiting period

Chamberlain decided to attend Kansas University. Upon hearing the

news, legendary KU basketball coach Phog Allen remarked: ‘‘Wilt

Chamberlain’s the greatest basketball player I ever saw. With him,

we’ll never lose a game; we could win the national championship

with Wilt, two sorority girls and two Phi Beta Kappas.’’ In spite of

Allen’s predictions, Kansas failed to win a NCAA championship

during Chamberlain’s two-year stint. But nonetheless, as a college

player he was as a man among boys. During his short stay at Kansas

the Saturday Evening Post ran a story titled, ‘‘Can Basketball Survive

Chamberlain,’’ leading the NCAA to make several rule changes to

curtail his dominance, and later Look magazine published an article

titled, ‘‘Why I Am Quitting College,’’ which was an exclusive piece

on his decision to leave Kansas. This media coverage was virtually

unprecedented for an African-American college athlete.

After leaving Kansas, Chamberlain had a brief one-year tour

with the Harlem Globetrotters before joining the Philadelphia Warri-

ors in 1959. In his first game with the Warriors, Chamberlain had 43

points and 28 rebounds. This was just a glimpse of what was to come.

Throughout his rookie year he scored fifty points or more five times,

en route to earning league Rookie of the Year and MVP honors,

CHANDLERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

473

marking the first time that anyone had ever won both awards the same

year. Throughout the next couple of years Chamberlain continued to

pick up individual honors. In his third year with the Warriors

Chamberlain continued his dominance and did the unthinkable,

scoring 100 points in a single game, after which the minuscule 4,124

fans in attendance ‘‘came pouring out of the stands and mobbed me.’’

As a result of his prowess on the court the NBA followed the NCAA’s

lead and made several rule changes of their own, simply because of

Chamberlain’s dominance.

Although Chamberlain continued to be a leader in scoring and

rebounding throughout his career (which included stints in San

Francisco and then later in Los Angeles), he was often maligned in the

national media. He was frequently labeled a ‘‘loser’’ because of his

team’s inability to beat Bill Russell and the Boston Celtics (although

he did win championships in 1967 and 1972), and he was often

viewed as a troublemaker because of his candid personality. In the

mid-1960s he was roundly criticized in the media for a story Sports

Illustrated published concerning his attitude with the NBA. Under the

headline: ‘‘My life in a Bush League,’’ Chamberlain criticized the

administrators, coaches, and players of the NBA. ‘‘For a sports

superstar who was supposed to be bubbling over with gratitude for

every second he got to play, those were some pretty harsh words. I

could understand why some people got upset,’’ Chamberlain re-

marked in his biography. But Chamberlain was never one to champi-

on black causes. In the late 1960s he drew the ire of the black

community when he denounced the Black Power movement while

supporting Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign, and he likewise

drew criticism from both blacks and whites alike when he expressed a

preference for white women. He was truly a colorful figure.

In 1978 Chamberlain was inducted into the NBA Hall of Fame in

his first year of eligibility and in 1996-1997 he was selected to the

NBA 50th Anniversary All-Star Team.

As the NBA’s first $100,000 man, Chamberlain had an enor-

mous impact on the rise of the NBA. His dominating play sparked the

interest of the country into a league that was forced to compete with

the more popular pastimes of baseball and football. He was personally

responsible for filling up arenas throughout the country as Americans

paid top dollar to see ‘‘Wilt the Stilt.’’ He was without question a one-

man show.

—Leonard N. Moore

F

URTHER READING:

Chamberlain, Wilt. View From Above: Sports, Sex, and Controversy.

New York, Dutton Books, 1992.

———. Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who

Lives Next Door. New York, Macmillan, 1973.

Frankl, Ron. Wilt Chamberlain. New York, Chelsea House, 1995.

Libby, Bill. Goliath: The Wilt Chamberlain Story. New York, Dodd,

Mead, 1977.

Chan, Charlie

See Charlie Chan

Chandler, Raymond (1888-1959)

Raymond Thornton Chandler started writing fiction in middle-

age, out of economic necessity, after being fired from his job. Despite

his late start and relatively brief career, Chandler’s influence on

detective fiction was seminal. He and fellow writer Dashiell Hammett

generally are seen as the Romulus and Remus of the hard-boiled

detective subgenre. Hammett’s experience as a Pinkerton detective

provided him with material very different from that of the genteel

murder mystery imported from England. Chandler, who cut his teeth

on the Black Mask school of ‘‘tough-guy’’ fiction, from the outset

shunned the classical mystery for a type of story truer to the violent

realities of twentieth-century American life. As he said, his interest

was in getting ‘‘murder away from the upper classes, the weekend

house party and the vicar’s rose garden, and back to the people who

are really good at it.’’

Chandler’s education and upbringing both hindered and spurred

his writing, for he came to the American language and culture as a

stranger. Although born in Chicago in 1888, at the age of seven he

was taken to London by his Anglo-Irish mother and raised there. After

a classical education in a public school, Chandler worked as a civil

servant and as a literary journalist, finding no real success in either

field. In 1912, on money borrowed from an uncle, he returned to the

United States, eventually reaching California with no prospects but,

in his words, ‘‘with a beautiful wardrobe and a public school accent.’’

Robert Mitchum as Philip Marlowe on the cover of The

Big Sleep.

CHANDLER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

474

For several years he worked at menial jobs, then became a bookkeep-

er. In 1917, he joined the Canadian Army and served as a platoon

commander in France. After the war, he began to work in the oil

business and rapidly rose to top-level management positions. In the

1920s, his drinking and womanizing grew steadily worse, until his

immoderation, along with the Great Depression, finally cost him his

job in 1932.

As a young man in London, Chandler had spent three years

working as a literary journalist and publishing romantic, Victorian-

style poetry on the side. Now, with only enough savings to last a year

or two, he turned back to writing in an attempt to provide a living for

his wife and himself. Initially, his literary sophistication inhibited his

attempts to write pulp fiction; however, he persevered through an

arduous apprenticeship and ultimately succeeded not only in writing

critically acclaimed commercial fiction but also in transcending the

genre. By the time of his death, Chandler had become a prominent

American novelist.

Chandler published his first story, ‘‘Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,’’

in the December 1933 issue of Black Mask. Under the editorship of

Joseph Shaw, it had emerged as the predominant pulp magazine.

Shaw promoted ‘‘hard-boiled’’ fiction in the Hammett mode, and

Chandler quickly became one of Shaw’s favorite contributors, pub-

lishing nearly two dozen stories in Black Mask between 1933 and

1941. Chandler’s first novel, The Big Sleep, was immediately com-

pared to the work of Dashiell Hammett and James Cain by critics,

who hailed Chandler as an exciting new presence in detective fiction.

His second novel, Farewell, My Lovely, appeared in 1940, followed

by novels The High Window (1942), The Lady in the Lake (1943), The

Little Sister (1949), The Long Good-bye (1954), and Playback (1958).

Chandler’s collection of short stories, The Simple Art of Murder,

contains, in addition to twelve pulp stories, an important and oft-

quoted essay on detective fiction.

Like his contemporary, Ernest Hemingway, Chandler’s impact

on American literature was fueled by his interest in style. His English

upbringing caused him to experience American English as a half-

foreign, fascinating language; and few American writers, with the

possible exceptions of Gertrude Stein and Hemingway, ever thought

more carefully about or cared more for the American language.

Chandler originated a terse, objective, colloquial style which has had

a vital influence on succeeding mystery writers, as well as on

mainstream literary writers, and even on Latin American authors such

as Hiber Conteris and Manuel Puig. Chandler skillfully cultivated a

subtle prose style that is actually literary while appearing to be plain

and colloquial. The hallmark of this style is the witty, exaggerated

simile. These similes often appear in the wise-cracks of Chandler’s

hero, Philip Marlowe; the effect being to add color to the dialogue and

to emphasize Marlowe’s rugged individualism. Chandler’s irrever-

ent, wise-cracking private detective set the tone for many of the hard-

boiled heroes who followed, such as Jim Rockford of television’s

The Rockford Files and Spenser, the protagonist of Robert B.

Parker’s novels.

Just as Chandler’s style is only superficially objective, becoming

subjective in its impressionistic realization of Marlowe’s mind and

emotions, Chandler’s fiction is hard-boiled only on the surface.

Marlowe never becomes as violent or as tough-minded as did some of

his predecessors, such as Hammett’s Continental Op. In fact, Mar-

lowe is sometimes, in the words of James Sandoe, ‘‘soft-boiled.’’

Lonely, disillusioned, depressive, Marlowe is yet somehow optimis-

tic and willing to fight injustice at substantial personal cost. Chandler

saw his hero as a crusading, but rather cynical, working-class knight

who struggles against overwhelming odds to help the powerless and

downtrodden. Marlowe maintains his chivalrous code in the face of

constant temptation and intimidation; his integrity is absolute, his

honesty paramount. Thus he manages to achieve some justice in a

corrupt, unjust world.

This archetypal theme places Chandler in the mainstream of

American fiction. The courageous man of action, the rugged individu-

alist who performs heroic deeds out of a sense of duty, has been a

staple of American literature since the early days of the nation. This

quintessential American hero originated in regional fiction, such as

James Fennimore Cooper’s Leather-Stocking Tales, and moved west-

ward with the frontier, appearing in many guises. The tough hero was

further developed by the dime novelists of the nineteenth century and

by early-twentieth-century progenitors of the Western genre. Ameri-

can detective story writers found a distinctly American hero waiting

for them to adapt to the hard-boiled sub-genre.

Another theme prevalent in Chandler’s work is the failure of the

American Dream. For Chandler, the crime and violence rampant in

newspaper headlines was rooted in the materialism of American life.

In their desperate grasping, Americans often stooped to extreme and

even unlawful measures. Chandler himself was not immune to the

lure of the greenback. He became an established Hollywood

screenwriter, though temperamentally unsuited to the collaborative

work. Notable among his film work is his and Billy Wilder’s 1943

adaptation for the screen of James M. Cain’s novel Double Indemnity.

Filmed by Paramount, the movie received an Academy Award

nomination for best script. The voice-over narration Chandler devised

for Double Indemnity became a convention of film noir. For Chandler,

the voice-over narration, so like the cynical, ironical voice of his

Marlowe, must have seemed natural.

After the death of Chandler’s beloved wife Cissy in 1954, he

entered a period of alcoholic and professional decline that continued

until his death in 1959. Like his hero, Philip Marlowe, Raymond

Chandler lived and died a lonely and sad man. But his contribution to

literature is significant, and his work continues to give pleasure to his

many readers.

—Rick Lott

F

URTHER READING:

Bruccoli, Matthew J. Raymond Chandler: A Descriptive Bibliog-

raphy. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1979.

Durham, Philip. Down These Mean Streets a Man Must Go: Raymond

Chandler’s Knight. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina

Press, 1963.

Gardiner, Dorothy, and Katherine Sorley Walker, editors. Raymond

Chandler Speaking. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

MacShane, Frank. The Life of Raymond Chandler. New York,

Dutton, 1976.

Marling, William. The American Roman Noir: Hammett, Cain, and

Chandler. Athens, University of Georgia Press, 1995.

———. Raymond Chandler. Boston, Twayne, 1986.

Speir, Jerry. Raymond Chandler. New York, Ungar, 1981.

Van Dover, J.K. The Critical Response to Raymond Chandler.

Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1995.

CHAPLINENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

475

Wolfe, Peter. Something More Than Night: The Case of Raymond

Chandler. Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling Green State University

Popular Press, 1985.

Chandu the Magician

This atmospheric radio adventure series first sounded its trade-

mark opening gong in 1932, appearing at the forefront of a popular

interest in magic and the occult which also produced Chandu’s more

famous fellow heroic students of the black arts, The Shadow and

Mandrake the Magician. Like any talented prestidigitator, Chandu

was able to appear in several different places simultaneously, and thus

managed to frustrate the world-dominating ambitions of his arch-

enemy Roxor in a feature film (1932) and a movie serial (1934) while

also holding down his day job in radio. Chandu disappeared in 1935

when the initial series of 15-minute adventures came to a close, but

the master magician had one more trick up his dapper sleeves,

reappearing out of the ether to a delighted public in 1948 in a new

production of the original scripts before vanishing for good in 1950.

Thus, in the words of radio historian John Dunning, Chandu The

Magician ‘‘. . . became one of the last, as well as one of the first,

juvenile adventure shows of its kind.’’

—Kevin Lause

F

URTHER READING:

Dunning, John. On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio.

New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Harmon, Jim, and Donald F. Glut. The Great Movie Serials. New

York, Doubleday, 1972.

Lackmann, Ron. Same Time, Same Station: An A-Z Guide to Radio

from Jack Benny to Howard Stern. New York, Facts On File, 1996.

Chanel, Coco (1883-1971)

Modern fashion has no legend greater than Gabrielle ‘‘Coco’’

Chanel. A strong woman, her life has inspired biographies, aphorisms,

and even a Broadway musical entitled ‘‘Coco.’’ She was one of the

most powerful designers of the 1920s, using knit, wool jersey, and

fabrics and styles associated with menswear to remake the modern

woman’s wardrobe with soft, practical clothing. She invented the

little black dress in the 1920s, and in the 1920s and 1930s, she made

the Chanel suit—a soft, cardigan-like jacket often in robust materials

with a skirt sufficiently slack to imply concavity between the legs—a

modern staple. Indomitable in life, Chanel enjoyed many affairs with

important men. One affair with a German officer prompted Chanel’s

eight year exile in Switzerland before reopening in 1954. She died in

1971 before one of her new collections was completed. The fragrance

Chanel No. 5, created in 1922, has driven the company with its

reputation and profit. As the chief designer since 1983, Karl Lagerfeld

has combined a loyalty to Chanel’s style signatures with an unmistak-

ably modern taste.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Baudot, Francois. Chanel. New York, Universe, 1996.

Leymarie, Jean. Chanel. New York, Skira/Rizzoli, 1987.

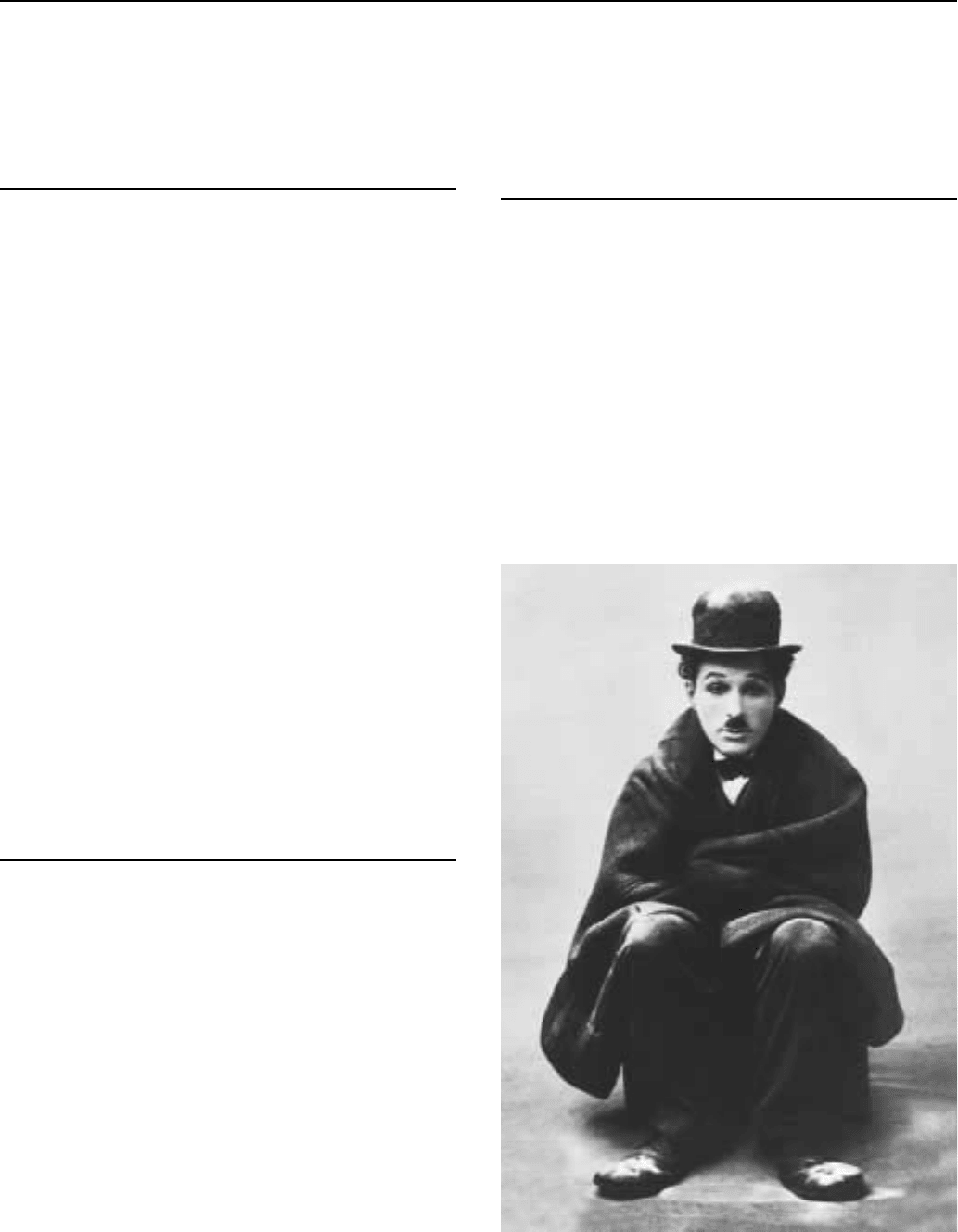

Chaplin, Charlie (1889-1977)

Comedian, actor, writer, producer, and director Charlie Chaplin,

through the universal language of silent comedy, imprinted one of the

twentieth century’s most distinctive and lasting cultural images on the

collective consciousness of the entire civilized world. In his self-

created guise the Tramp, an accident-prone do-gooder, at once

innocent and devious, he sported a toothbrush mustache, baggy pants,

and tattered tails, tilting his trademark bowler hat and jauntily

swinging his trademark cane as he defied the auguries of a hostile

world. The Little Tramp made his first brief appearance in Kid Auto

Races at Venice for Mack Sennett’s Keystone company in 1914, and

bowed out 22 years later in the feature-length Modern Times (United

Artists, 1936). In between the Tramp films, Chaplin made countless

other short-reel silent comedies, which combined a mixture of Victo-

rian melodrama, sentiment, and slapstick, enchanted audiences world-

wide, and made him an international celebrity and the world’s highest

Charlie Chaplin

CHAPLIN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

476

paid performer. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, 86 years after

he first appeared on the flickering silent screen, Chaplin was still

regarded as one of the most important entertainers of the twentieth

century. He was (and arguably still is) certainly the most universally

famous. On screen, he was a beloved figure of fun; off-screen,

however, his liberal political views brought accusations of Commu-

nism and close official scrutiny, while his notorious private life

heaped opprobrium on his head. Despite his personal failings, howev-

er, Chaplin’s Tramp and astonishing achievements made him, in the

words of actor Charles Laughton, ‘‘not only the greatest theatrical

genius of our time, but one of the greatest in history.’’

Born Charles Spencer Chaplin in London on April 16, 1889, the

man who would become one of the world’s wealthiest and most

instantly recognizable individuals was raised in circumstances of

appalling deprivation, best described as ‘‘Dickensian.’’ The son of

music hall entertainers who separated shortly after his birth, Chaplin

first took the stage spontaneously at age five when his mentally

unstable mother, Hannah Chaplin, lost her voice in the midst of a

performance. He sang a song and was showered with pennies by the

appreciative audience. Hannah’s health and career spiraled into

decline soon after, and she was committed to a state mental institu-

tion. She was in and out of various such places until 1921, when

Charlie brought her to live in California until her death in 1928.

Meanwhile, the boy and his elder half-brother, Sydney, found them-

selves in and out of state orphanages or living on the streets, where

they danced for pennies. Forced to leave school at age ten, Charlie

found work with various touring theatrical companies and on the

British vaudeville circuit as a mime and roustabout. In 1908 he was

hired as a company member by the famous vaudeville producer Fred

Karno, and it was with Karno’s company that he learned the craft of

physical comedy, developed his unique imagination and honed his

skills while touring throughout Britain. He became a leading Karno

star, and twice toured the United States with the troupe. While

performing in Boston during the second of these tours in 1912, he was

seen on stage by the great pioneering filmmaker of the early silent

period Mack Sennett, who specialized in comedy. Sennett offered the

diminutive English cockney a film contract, Chaplin accepted, and

joined Sennett’s Keystone outfit in Hollywood in January 1914.

Chaplin, soon known to the world simply as ‘‘Charlie’’ (and to

the French as ‘‘Charlot’’), made his film debut as a villain in the 1914

comedy Making a Living. In a very short time, he was writing and

directing, as well as acting, and made numerous movies with Sennett’s

famous female star, Mabel Normand. His career thrived, and he was

lured away by the Essanay company, who offered him a contract at

$1,250 a week to make 14 films during 1915. They billed Chaplin as

‘‘the world’s greatest comedian’’ and allowed him to control all

aspects of his work including production, direction, writing, casting,

and editing. At Essanay Chaplin made a film actually called The

Tramp, and, in the course of the year, refined and perfected the

character into, as film historian Ephraim Katz wrote, ‘‘the invincible

vagabond, the resilient little fellow with an eye for beauty and a

pretense of elegance who stood up heroically and pathetically against

overwhelming odds and somehow triumphed.’’

In February 1916, however, Chaplin left Essanay for Mutual and

a stratospheric weekly salary of $10,000 plus a $150,000 bonus, sums

that were an eloquent testimony to his immense popularity and

commercial worth. Among his best films of the Mutual period are The

Rink (1916), Easy Street, and The Immigrant (both 1917) and during

this period he consolidated his friendship and frequent co-starring

partnership with Edna Purviance. By mid-1917, he had moved on to a

million-dollar contract with First National, for whom his films

included Shoulder Arms (1918) and, famously, The Kid (1921). This

last, in which comedy was overlaid with sentiment and pathos,

unfolded the tale of the Tramp caring for an abandoned child,

unveiled a sensational and irresistible performance from child actor

Jackie Coogan, and marked Chaplin’s first feature-length film. Mean-

while, in 1919, by which time he had built his own film studio,

Chaplin had joined Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W.

Griffith to form the original United Artists, designed to allow artistic

freedom free of the conventional restraints of studio executives, a

venture of which it was famously said that it was a case of ‘‘the

lunatics taking over the asylum.’’ As he moved from shorts to longer

features, Chaplin increasingly injected his comedy with pathos.

In 1918, Chaplin had a liaison with an unsuitable 16-year-old

named Mildred Harris. He married her when she claimed pregnancy,

and she did, in fact, bear him a malformed son in 1919, who lived only

a couple of days. The ill-starred marriage was over months later, and

divorce proceedings were complete by November of 1920. In 1924,

shortly before location shooting began in the snowy wastes of the

Sierra Nevada for one of Chaplin’s great feature-length masterpieces,

The Gold Rush (1925), he found a new leading lady named Lillita

Murray, who had appeared in The Kid. She was now aged 15 years

and 10 months. He changed her name to Lita Grey, became involved

with her and, once again called to account for causing pregnancy,

married her in November of 1924. By the beginning of 1927, Lita had

left Charlie, taking their two sons, Charles Spencer Jr. and Sidney,

with her. Their divorce was one of the most public displays of

acrimony that Hollywood had witnessed. Lita had been replaced by

Georgia Hale in The Gold Rush, a film whose meticulous preparation

had taken a couple of years, and whose finished version was bursting

with inspirational and now classic set pieces, such as the starving

Tramp making a dinner of his boots.

In 1923, Chaplin had departed from his natural oeuvre to direct a

‘‘serious’’ film, in which he did not appear himself. Starring Edna

Purviance and Adolphe Menjou, A Woman of Paris was, in fact, a

melodrama, ill received at the time, but rediscovered and appreciated

many decades later. By the end of the 1920s, the sound revolution had

come to the cinema and the silents were a thing of the past. Chaplin,

however, stood alone in famously resisting the innovation, maintain-

ing that pantomime was essential to his craft, until 1936 when he

produced his final silent masterpiece Modern Times. Encompassing

all his comic genius, the film, about a demoralized factory worker, is

also a piece of stringent social criticism. It co-starred Paulette

Goddard, whom he had secretly married in the Far East (they divorced

in 1942), and ends happily with an eloquent and archetypal image of

the Tramp waddling, hand-in-hand, with his girl, down a long road

and disappearing into the distance. With World War II under way,

Chaplin made his entry into sound cinema with The Great Dictator

(1940). Again co-starring with Goddard, he essayed the dual role of a

humble barber and a lookalike dictator named Adenoid Hynkel. A

scathing satire on Adolf Hitler, the film is an undisputed masterpiece

that, however, caused much controversy at the time and brought

Chaplin into disfavor in several quarters—not least in Germany. It

garnered five Oscar nominations and grossed a massive five million

dollars, the most of any Chaplin film, for United Artists.

The Great Dictator marked the last Chaplin masterpiece. Mon-

sieur Verdoux (1947) featured Chaplin as a Bluebeard-type murderer,

fastidiously disposing of wealthy women, but it manifested a dark

political message, ran foul of the censors, and was generally badly

received. He himself regarded it as ‘‘the cleverest and most brilliant

CHARLESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

477

film I have yet made,’’ and certain students of his work have come to

regard it as the most fascinating of the Chaplin films, redolent with his

underlying misogyny and rich in savage satire. By 1947 he had been

the victim of a damaging paternity suit brought by starlet Joan Barry.

In a bizarre judgment, based on forensic evidence, the court found in

his favor but nonetheless ordered him to pay child support, and that

year he received a subpoena from the HUAC, beginning the political

victimization that finally drove him from America. He had, however,

finally found what would be lifelong personal happiness with Oona

O’Neill, daughter of playwright Eugene. The couple married in 1943,

when she was 18 and he 54 and had eight children, one of whom

became actress Geraldine Chaplin, who played Charlie’s mother

Hannah in Richard Attenborough’s film, Chaplin (1992).

October 1952 saw the premiere of what is perhaps Charlie

Chaplin’s most personal film, Limelight. It is a collector’s piece

insofar as it features Chaplin and Buster Keaton together for the first

and only time. It also marked the debut of the then teenaged British

actress Claire Bloom but, most significantly, this tale of a broken-

down comedian is redolent of his own childhood background in its

return to the long gone era of music hall, and the slum streets of

Victorian London. Remarkable for its atmosphere, it is, however,

mawkish and clumsily shot. After this, there were only two more

features to come, neither of which were, or are, considered successful.

A King in New York (1957) is an attack on Mccarthyism; A Countess

from Hong Kong (1967), starring Marlon Brando and Sophia Loren, is

a lightweight comedy that misfired disastrously to become the great

filmmaker’s biggest single disaster and an unworthy swan song.

By the time Limelight was released, Chaplin had been accused of

Communist affiliations. It was the culmination of many years of

resentment that he had not adopted American citizenship, and had

further outraged the host country where he found fame by his

outspoken criticisms and his unsuitable string of liaisons with teenage

girls. He did not return from his trip to London, but settled with his

family at Corsier sur Vevey in Switzerland, where, by then Sir

Charles Chaplin, he died in his sleep on December 25, 1977. On

March 1, 1978, his body was stolen from its grave, but was recovered

within a couple of weeks, and the perpetrators were found and tried

for the theft.

By the time of his death, America had ‘‘forgiven’’ Chaplin his

sins. On April 16, 1972, in what writer Robin Cross called ‘‘a triumph

of Tinseltown’s limited capacity for cosmic humbug’’ Chaplin, old,

overweight, frail, and visibly overcome with emotion, returned to

Hollywood to receive a special Oscar in recognition of his genius.

That year, too, his name was added to the ‘‘Walk of Fame’’ in Los

Angeles, and a string of further awards and honors followed, culmi-

nating in his knighthood from Queen Elizabeth in London in March,

1975. Charlie Chaplin, who published My Autobiography in 1964,

and My Life in Pictures in 1974, once said, ‘‘All I need to make a

comedy is a park, a policeman, and a pretty girl.’’ His simple, silent

comedies have grown more profound as the world has grown increas-

ingly chaotic, noisy, and troubled.

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Robinson, David. Chaplin: His Life and Art. London, William

Collins Sons & Co., 1985.

Douglas, Ann. ‘‘Charlie Chaplin.’’ Time. June 8, 1998, 118-121.

Katz, Ephraim. The Film Encyclopedia. New York,

HarperCollins, 1994.

Karney, Robyn, and Robin Cross. The Life and Times of Charlie

Chaplin. London, Green Wood Publishing, 1992.

Kerr, Walter. The Silent Clowns. New York, Plenum Press, 1975.

Shipman, David. The Great Movie Stars. New York, Hill & Wang, 1979.

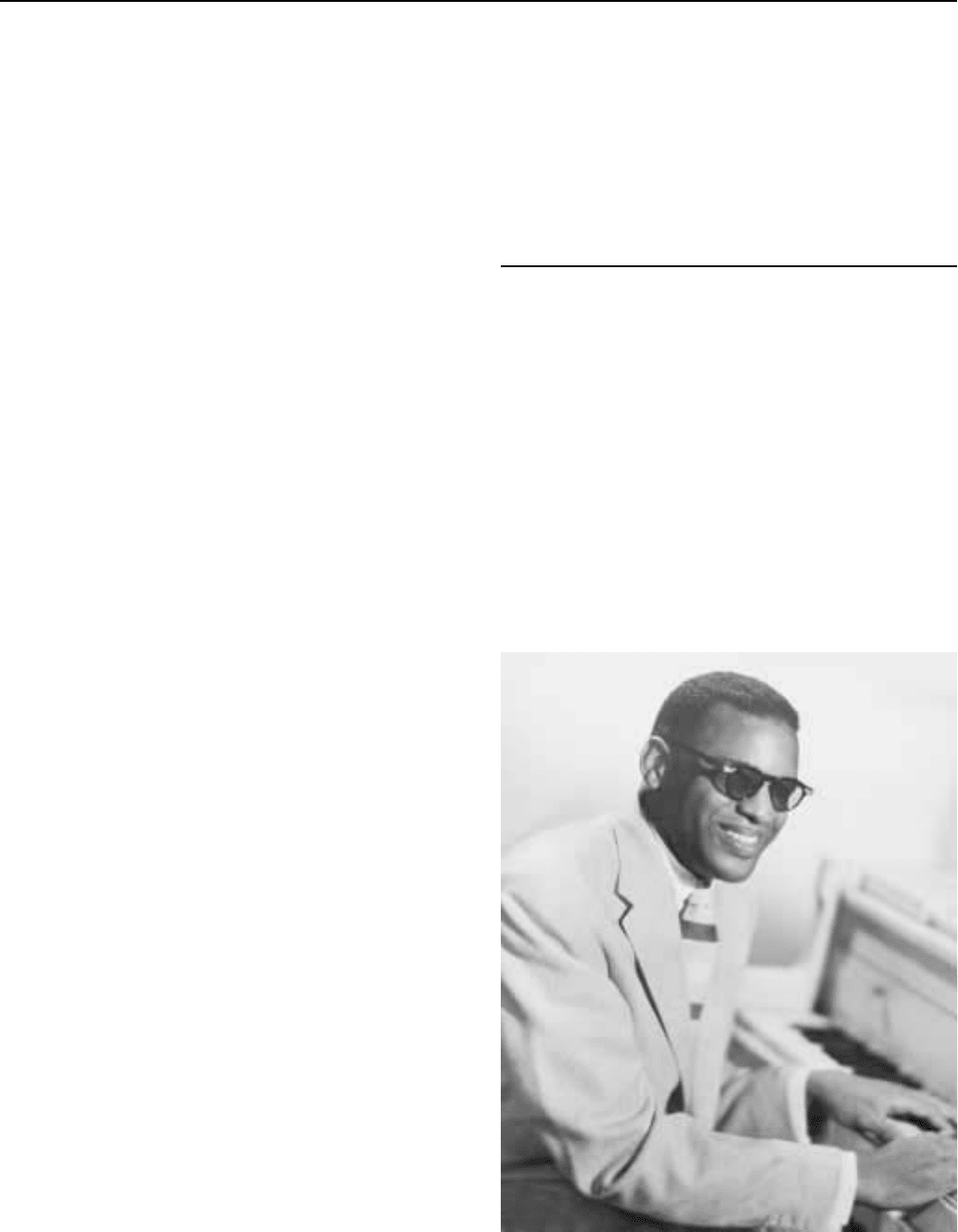

Charles, Ray (1930—)

Musician Ray Charles is generally considered a musical genius,

and is so in many fields. He has had enormous success in jazz, blues,

soul music, country and western, and crossover pop. Acknowledged

as an expert vocalist, pianist, saxophonist, and all-around entertainer,

Charles first burst into popular attention in the 1950s as the virtual

inventor of soul music.

Charles was born Ray Charles Robinson in Albany, Georgia, on

September 23, 1930, and raised in Greenville, Florida. A neighbor

gave Charles piano lessons after Charles had taught himself how to

play at the age of three. This neighbor owned a small store that served

as a juke joint as well. Charles not only took piano lessons in the juke

joint, he also absorbed the blues, jazz, and gospel music on the jukebox.

When he was six, Charles lost his sight to glaucoma. He

continued his music studies at the St. Augustine School for the Deaf

and Blind, where he studied for nine years, learning composition and

a number of instruments. Upon leaving the school, he worked in a

Ray Charles

CHARLIE CHAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

478

number of settings with many different groups in the Florida area.

Eventually, he moved to California and recorded with a trio very

much in the style of Nat King Cole.

In 1952, Charles signed with Atlantic Records in a move that

greatly aided both parties: Atlantic gave him free artistic reign, and

Charles responded with a string of hits. These included songs that

have become classic rhythm and blues features: ‘‘I Got a Woman,’’

‘‘Hallelujah I Love Her So,’’ ‘‘Drown in My Own Tears,’’ and

‘‘What’d I Say.’’ Charles described his music at the time as ‘‘a

crossover between gospel music and the rhythm patterns of the

blues.’’ This combination violated a long-standing taboo separating

sacred and secular music, but the general public did not mind, and

soul music, a new musical genre, was born. Many of his fans consider

this Atlantic period as his greatest.

Charles once stated that he became actively involved in the Civil

Rights movement when a promoter wanted to segregate his audience.

Charles, an African American, said that it was all right with him if all

the blacks sat downstairs and all the whites in the balcony. The

promoter said that Charles had it backwards; his refusal to perform the

concert eventually cost him a lawsuit, but he was determined to

support Martin Luther King openly and donated large sums of money

to his cause.

Charles later moved to ABC/Paramount and branched out into

country and western music. In 1962, his country and western album

was number one on the Billboard list for fourteen weeks.

Charles’s mastery of a number of musical genres and ranking

among the very best of America’s vocalists (such as Frank Sinatra,

Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole) is amply demon-

strated by the fiftieth-anniversary collection. Although containing

songs even his strongest fans will not like, there are great moments on

every tune no matter what the genre. Ray Charles became more than

just another singer; he became a representative of his times.

—Frank A. Salamone, Ph.D.

F

URTHER READING:

Alkyer, Frank. ‘‘Genius and Soul: The 50th Anniversary Collec-

tion.’’ Down Beat. Vol. 65, No. 1, January 1998, 54.

Genius & Soul: The 50th Anniversary Collection (sound record-

ing). Rhino.

Sanjek, David. ‘‘One Size Does Not Fit All: The Precarious Position

of the African American Entrepreneur in Post-World War II

American Popular Music.’’ American Music. Vol. 15, No. 4,

Winter 1997, 535.

Silver, Marc. ‘‘Still Soulful after All These Years.’’ U.S. News &

World Report. Vol. 123, No. 11, September 22, 1997, 76.

Charlie Chan

The Chinese detective Charlie Chan remains author Earl Derr

Biggers’ (1884-1933) greatest legacy. Biggers based his fictional

Asian sleuth on Chang Apana, a Chinese American police detective

who lived in Honolulu. Biggers’ introduced Chan in The House

without a Key in 1925, the first of six Chan novels. Beginning in 1926,

the Chan character hit the silver screen and was eventually featured in

more than thirty films. Three different actors portrayed Chan in films:

Warner Oland, Sidney Toler, and Roland Winters. While Chan’s

character was based on an Asian person, his resemblance to Chinese

Americans was remote. White actors played Chan as a rotund, slow-

moving detective who spoke pithy sentences made to sound like

Confucian proverbs. In contrast to the evil Fu Manchu (another film

character), Chan was a hero. But ultimately, his depiction created a

new stereotype of Asian Americans as smart, yet inscrutable

and inassimilable.

—Midori Takagi

F

URTHER READING:

Busch, Frederick. ‘‘The World Began with Charlie Chan.’’ The

Georgia Review. Vol. 43, Spring 1989, 11-12.

Henderson, Lesley, editor. Twentieth-Century Crime and Mystery

Writers. London, St. James Press, 1991.

Charlie McCarthy

The wooden puppet known as Charlie McCarthy was a preco-

cious adolescent sporting a monocle and top hat, loved by the public

for being a flirt and a wise-guy, and a raffish brat who continually got

the better of his ‘‘guardian,’’ mild-mannered ventriloquist Edgar

Bergen (1903-1978). The comedy duo got their start in vaudeville and

gave their last performance on television, but—amazingly—they

found their greatest fame and success in the most unlikely venue for

any ventriloquist: radio. Since the need for illusion was completely

obviated by radio, whose audiences wouldn’t be able to tell whether

or not Bergen’s lips were moving, the strength of Bergen and

McCarthy as a comedy team was the same as it was for Laurel and

Hardy or Abbott and Costello: they were funny. Bergen created and

maintained in Charlie a comic persona so strong that audiences almost

came to think of him as a real person. Eventually, ‘‘the woodpecker’s

pin-up boy’’ was joined by two other Bergen creations, hayseed

Mortimer Snerd and spinster Effie Klinker, but neither surpassed

Charlie in popularity. A broadcast sensation, Bergen and McCarthy

also guest-starred in several films, including a couple that gave

Charlie the chance to continue his radio rivalry with W. C. Fields. Not

until the advent of television would such puppets as Howdy Doody

and Kukla and Ollie gain such universal renown. But unlike these

latter-day characters, Charlie was designed to appeal equally to adults

as to children.

As a child growing up in Chicago, Edgar Bergen discovered that

he had the talent to ‘‘throw his voice,’’ and he put this gift to

mischievous purposes, playing such pranks on his parents as making

them think that an old man was at the door. When he reached high

school age, young Edgar studied ventriloquism seriously and then

commissioned the carving of his first puppet to his exacting specifica-

tions: thus was Charlie McCarthy born, full-grown from the head—

and larynx—of Bergen. Although he began pre-med studies, Bergen

quickly abandoned education for vaudeville. Before long, Bergen and

McCarthy were a success, touring internationally. When vaudeville

began to fade in the 1930s, Edgar and Charlie switched to posh

nightclubs, which eventually led to a star-making appearance on

Rudy Vallee’s radio show. By 1937, Bergen and McCarthy had their

own show, and its phenomenal success lasted for two decades.