Graef M. Introduction to conventional transmission electron microscopy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

188 The transmission electron microscope

High

Tension

+

-

V

F

Grid or

Wehnelt

Anode

Electrical

Ground

I

F

R

W

R

0

<0

>0

Gun

Crossover

(a)

(b)

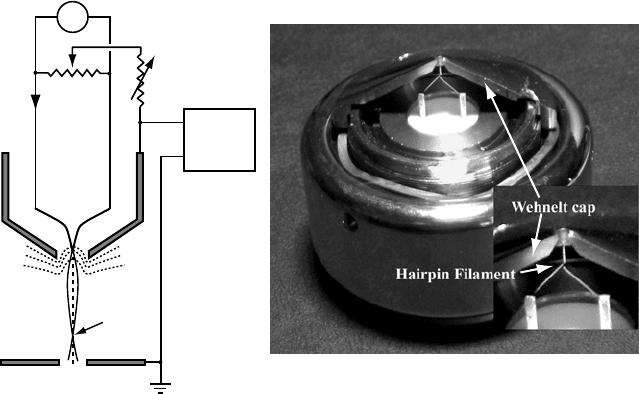

Fig. 3.23. (a) Schematic

of a thermionic electron gun; (b) photograph of the cross-sectioned

Wehnelt assembly of the JEOL 120CX microscope.

filaments, with a work function of W = 4.5 eV, are operated at 2600–2800 K.

Single-crystal LaB

6

emitters have a work function of 2.7 eV, and are operated in

the range 1700–1900 K.

The anode surface is kept at ground potential, and the high-tension supply gen-

erates a voltage (the acceleration voltage E) between the filament tip and the anode

plate. The filament is kept at a negative potential of −E V with respect to the anode,

so that electrons emitted from the tip are accelerated towards the anode. Thermal

emission occurs not only from the tip but also from the flanks of the tip, and this

would lead to electrons traveling at large angles with respect to the optical axis. To

prevent emission from the filament flanks, a conical surface is introduced around

the filament. This surface is known as the grid or, more commonly, the Wehnelt

cap. The grid is kept at a small negative voltage with respect to the tip by means

of a variable resistor R

W

. On the microscope console the resistance R

W

can be

changed by means of the gun bias control. The bias resistor is tied into the filament

heating circuit, so that the energy of the accelerated electron will always be E eV,

regardless of the bias setting.

The negative Wehnelt cap produces a zero-potential contour, indicated with dot-

ted lines in Fig. 3.23(a). The bias voltage is set so that this contour intersects the

filament close to the tip. Regions along the flanks of the filament experience a neg-

ative potential and hence thermionic emission will be suppressed. Changing the

gun bias amounts to changing the location of this zero-potential surface, and hence

3.7 Basic electron optics: electron guns 189

the size of the emitting region. If the bias voltage is too large then there will be

no intersection between the zero-potential contour and the tip, which means that

there will be no emission. If the bias voltage is too low, then the size of the emitting

region will be large, and therefore the gun brightness will decrease. There is an op-

timal gun bias setting for which the brightness is maximized. This voltage setting

depends sensitively on the precise location of the tip within the Wehnelt cap and

on the shape of the Wehnelt cap. Typical filament currents at maximum brightness

are about 100

µA for tungsten filaments and this is indicated by the beam current

on the microscope console.

3.7.3.2 Schottky and field emission electron guns

Schottky and field emission electron guns are quite similar in construction, so we

will describe them both in this section. A Schottky electron gun employs a tungsten

single-crystal filament with a flat circular (100) facet normal to the optical axis;

the diameter of this facet is typically around 1

µm. The filament is coated with

a thin ZrO layer, which reduces the work function from 4.5 to about 2.8 eV. The

operating temperature can hence also be lowered to about 1800 K. A suppressor cap

(see Fig. 3.24a) surrounds the filament so that only the very tip protrudes through

the cap. The suppressor cap takes on the role of the Wehnelt cap in a thermionic

gun: a voltage of −2 kV prevents electron emission from the flanks of the filament

crystal.

An extractor plate, kept at a positive potential in the range 2–7 kV, provides

the electric field needed to extract electrons from the tip. The field is inversely

proportional to the tip radius so that fields of several volts per nanometer can be

obtained. The electrons are then accelerated by the anode plate and emerge through

a small hole along the optical axis. The electrons appear to emanate from a point

F

Suppressor

Anode

Extractor

Gun lens

Gun

Crossover

Virtual

Source

Filament

Tip

(a)

(b)

Fig. 3.24. Schematic illustration of a Schottky electron gun.

190 The transmission electron microscope

inside the filament (Fig. 3.24b), the virtual source with a size of about 10 nm, and

do not form a gun cross-over, so that a gun lens is needed to intersect the electron

trajectories with the optical axis. The gun lens is an electrostatic lens with a variable

potential in the range 0.5–2 kV. A strongly excited gun lens will bring the gun cross-

over close to the gun, whereas a weakly excited gun lens will have a lower cross-over

(closer to the first condensor lens). The emission current is typically about 150

µA.

A cold field emission gun is very similar in construction to the Schottky gun. It

has the same components: suppressor, extractor, anode, and gun lens. The filament

tip (typically tungsten) has a radius of about 100 nm and the extractor voltage

provides a field strength sufficient to cause electrons near the Fermi level to tunnel

through the barrier potential (which is narrow because of the applied field). The

gun vacuum for a cold field emitter must be around 10

−8

Pa, whereas a Schottky

emitter requires about 10

−6

Pa. The Schottky emitter also provides a more stable

emission current over a long period of time. Cold field emitter tips must be flashed

regularly, to remove contaminants from the emitter surface. Parameter ranges for

both Schottky and cold field emission guns can be found in Table 3.2.

3.7.4 Beam energy spread and chromatic aberration

Electrons which leave a thermionic emission tip have initial energies of at least the

work function W . In this energy range the Fermi–Dirac distribution function (3.46)

reduces to a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution (taking the zero of the energy scale

at the Fermi level):

f (E, T ) =

1

1 + e

−E /k

B

T

≈ e

−E /k

B

T

. (3.59)

We can then use equation (3.51) to define the normalized energy distribution g(E)

[HK89b]:

g(E)dE ≡

d j

z

j

z

=

E

(k

B

T )

2

f (E, T )dE. (3.60)

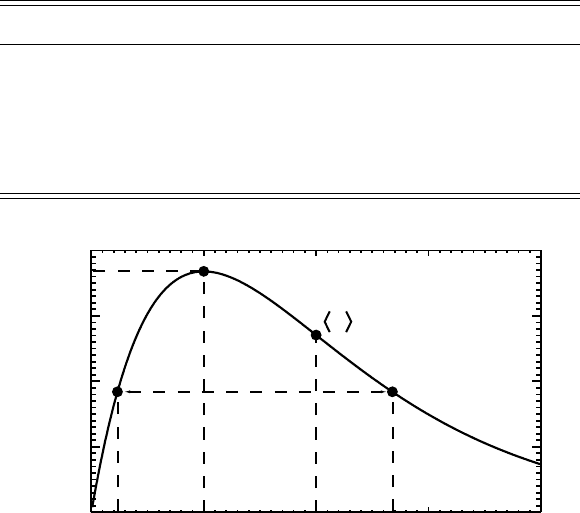

The distribution k

B

Tg(E) is shown in Fig. 3.25 as a function of the variable E/k

B

T .

The mean electron energy is given by E=2k

B

T , the most probable energy

corresponds to the maximum of the curve at E

m

= k

B

T , and the energy spread

(full width at half maximum, or FWHM) is given by E = 2.446k

B

T . Table 3.3

shows the relevant energies for a tungsten emitter and a LaB

6

emitter, using a typical

operating temperature. The last column shows the corresponding expressions for

a thermal field emission gun. The energy spread for field emission is in the range

0.2–0.4 eV. The energy distribution should be superimposed on the final energy of

the electrons after acceleration.

3.7 Basic electron optics: electron guns 191

Table 3.3. Energy distribution parameters for a tungsten emitter

and a LaB

6

emitter; energies in eV, temperature in K. The last

column shows the explicit expressions for a thermal field

emitter [HK89b].

W LaB

6

Thermal field emission

Work function 4.5 2.7

Temperature 2800 1900

f (W, T )7.95 × 10

−9

6.89 × 10

−8

E 0.482 0.327 π pd cot(π pd)

E

m

0.241 0.164 dπ p/ sin(π p)

E 0.590 0.400 k

B

T [ln p − ln(1 − p)]

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

01234

k

B

Tg(E)

E/k

B

T

E

m

E

∆E

Fig. 3.25. Normalized energy distribution k

B

Tg(E) as a function of E/ k

B

T for thermionic

emission. The mean energy, most probable energy, and energy spread are indicated.

It was discovered experimentally by Boersch in 1954 [Boe54] that there is an

anomalous broadening of the energy distribution for thermionic emission, that the

energy distribution tends to become symmetric around its maximum E

m

(which

is not the case for the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution shown in Fig. 3.25), and

that the mean energy E is shifted. These effects increase with increasing beam

current. Although there is at present no single theory explaining all of these effects,

it has been shown that they are due to stochastic Coulomb interactions between the

electrons, whenever they come close together (as in a cross-over). This has led to

modifications of the shape of the Wehnelt cap; the net result of these modifications is

that the cross-over moves further away from the cathode (telescopic effect) and can

sometimes be completely avoided. The Boersch effect occurs whenever electrons

are forced into a narrow beam, e.g. in electron lithography where high probe currents

192 The transmission electron microscope

and small probe diameters are required. The energy spread of a thermionic gun is

increased to about 1 eV by the Boersch effect.

Recent developments in electron optical design of monochromators make it pos-

sible to reduce the energy spread of the beam down to the range 50–200 meV. Such

energy filters are becoming available on dedicated microscopes and may revolu-

tionize the study of electron energy loss mechanisms.

Chromatic aberration is caused by the fact that the focal length of a lens depends

on the wavelength and hence on the electron energy. Small fluctuations in the high-

voltage supply or in the lens power supply will cause small variations in λ (and thus

in

ˆ

) and in B(z), respectively. There are four important sources of fluctuations

and/or energy changes in a microscope:

(i) intrinsic energy spread of the electrons leaving the filament, typically E/E ≈ 10

−5

(see Tables 3.1 and 3.2);

(ii) high-voltage instabilities, V / V ≈ 10

−6

min

−1

;

(iii) fluctuations I /I of the lens currents;

(iv) energy losses in the specimen.

As a consequence of these fluctuations the focal length f of a magnetic lens will

no longer be precisely defined and instead we can talk about the defocus spread

[Spe88]:

= C

c

σ

2

(V )

V

2

+

4σ

2

(I )

I

2

+

σ

2

(E)

E

2

1/2

, (3.61)

where σ indicates the standard deviation. The first term represents fluctuations of

the acceleration voltage, the second represents fluctuations of the focal length due

to fluctuations of the lens current I (recall that the focal length depends on the

square of the field B(z), hence the factor of 4 above), and the last term corresponds

to the intrinsic energy spread of the electron gun, including the Boersch effect. The

chromatic aberration coefficient C

c

, typically expressed in mm, can be written in

terms of the axial field distribution B(z) as [HK89a]:

C

c

=

e

8m

ˆ

.

z

1

z

0

B

2

(z)h

2

(z)dz, (3.62)

where h(z) is a paraxial trajectory that leaves an axial object point with unit slope.

The net effect of chromatic aberration is that the image of a point will be blurred

into a disk. Chromatic aberration can be removed in principle by combining the lens

with an electrostatic mirror with negative C

c

. We will return to chromatic aberration

in Chapter 10.

3.7 Basic electron optics: electron guns 193

3.7.5 Beam coherence

The primary purpose of the electron gun and the illumination system as a whole is

to create a stream of electrons with a well-known reference state. We will see in

Chapter 5 that the equations describing the interaction between beam electrons and

the sample can be solved when the incident electron can be represented by a plane

wave. We must, therefore, introduce a measure for how well a beam electron can

be described by a plane wave.

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle states that the product of the uncertainty or

spread in energy and the uncertainty in time must be larger than Planck’s constant, or

Et > h. (3.63)

For a thermionic gun with an energy spread E of 1 eV we find that t ≈ 4 ×

10

−15

s. During this time interval the electron travels a distance λ

tc

, known as the

temporal coherence length, given by

λ

tc

= ct

/

1 −

1

γ

2

. (3.64)

At 200 kV, we have λ

tc

= 861 nm. The temporal coherence length of optical lasers

varies from a few centimeters to many meters. The temporal coherence length

would be infinite for an electron gun with zero energy spread, i.e. a perfectly

monochromatic electron gun. The longer the temporal coherence length, the more

“identical” the beam electrons are.

Ideally, all beam electrons would emanate from a single point on the filament. In

reality, the electrons that reach the sample appear to leave a point which coincides

with the gun cross-over for the thermionic gun and the virtual source for the field

emission gun. This virtual source has a finite lateral extent (lateral means normal

to the optical axis) of a few nanometers for field emission guns to 10–50

µm for

thermionic guns. We will see in Section 3.8 that in most cases the electron beam

passes through an aperture (the second condensor aperture) before reaching the

sample. The beam divergence angle θ

c

subtended by this aperture at the sample can

be used to define the transverse coherence width or spatial coherence width λ

sc

of

the illumination:

λ

sc

=

λ

2πθ

c

. (3.65)

If two object points A and B are separated from each other by a distance r <λ

sc

,

then the amplitudes of the waves scattered by these two points must be added before

194 The transmission electron microscope

converting to intensities:

I =|

A

+

B

|

2

; (3.66)

=|ψ

A

|

2

+|ψ

B

|

2

+

A

∗

B

+

∗

A

B

; (3.67)

= I

A

+ I

B

+ I

AB

(coherent). (3.68)

If the separation between the two object points is much larger than the coherence

width, then the final scattered intensity is given by

I = I

A

+ I

B

=|ψ

A

|

2

+|ψ

B

|

2

(incoherent). (3.69)

The difference between the coherent and incoherent cases is the interference term

I

AB

. The intermediate range, i.e. distances comparable to the coherence width, is

described by the theory of partial coherence.

Under normal observation conditions with a thermionic electron gun, the illumi-

nating aperture is incoherently filled with statistically independent electron sources.

For field emission systems the entire illuminating aperture is coherently filled and

the transverse coherence width at the aperture plane [SZ92] is defined by

λ

sc,a

=

λ

2πθ

s

, (3.70)

where θ

s

is the angle subtended by the source at the aperture plane. A smaller

aperture radius will increase the transverse coherence width, as will a decrease of

the acceleration voltage.

It is intuitively clear that an infinitely small aperture will only allow one single

wave vector to contribute to the incident electron beam, hence a pure plane wave is

obtained. Experimentally this cannot be established without severe losses in current

density. For high-resolution observations, where interference between the different

diffracted beams is employed to obtain structural images, the coherence width is

important and an appropriate choice of the condensor aperture radius must be made

by the microscope operator. A smaller aperture will increase the coherence width but

at the same time the current density will be reduced, thus requiring longer exposure

times. Image contrast caused by interference from beams emanating from regions

of the sample within the coherence width is called phase contrast. In Chapter 10

we will deal extensively with various types of phase contrast.

For in-depth discussions of coherence in optical and electron optical systems

we refer the reader to [Goo68, Chapter 6], [Spe88, Chapter 4], [SZ92, Chapter 8],

and [BW75, Section 7.5.8].

3.8 The illumination stage: prespecimen lenses 195

3.7.6 How many electrons are there in the microscope column?

It is a simple exercise to calculate how many beam electrons are present in the

microscope column at any given moment in time. A beam current I of 1 nA cor-

responds to 6.25 × 10

18

electrons C

−1

× 10

−9

Cs

−1

,or6.25 × 10

9

electrons s

−1

.

Electrons accelerated by a potential of E volts travel at a velocity v = βc, and in

one second travel a distance of = v m. If electrons are emitted from the gun at

regular intervals in time (a reasonable approximation), then we can compute the

linear electron density n

e

per nA of beam current in the column:

n

e

=

6.25 × 10

9

v

.

At E = 200 kV, electrons travel at a velocity of v = 0.695c, which results in a linear

electron density of about 30 electrons m

−1

nA

−1

. The average distance between

consecutive electrons is then about 3 cm, which is much larger than the thickness of

the sample. As far as the sample is concerned, it is thus a very good approximation

to consider each beam electron separately, and this is precisely what the equations

derived in Chapter 2 accomplish.

This illustrates once again that an electron diffraction experiment is, in fact,

the quintessential quantum mechanics experiment; individual electrons are sent

through a sample with a very large number of “slits”, and since we do not attempt

to determine precisely which “slit” the electron traveled through, an interference

pattern will result at the detector.

It takes an electron a time t = z

0

/v to traverse a sample of thickness z

0

; for

a 100 nm thick sample, and a 200 kV electron, t = 4.8 × 10

−16

s. This time

interval is about four orders of magnitude shorter than the typical duration of a

single cycle of a lattice vibration, and therefore it is a very good approximation

to consider the atoms to be stationary throughout the interaction with the beam

electron. The time interval between two consecutive electrons is 1.6 × 10

−10

s for

a 1 nA beam of 200 kV electrons; during this time interval atoms have gone through

about 100 vibration periods, which means that there is no correlation between the

position of an atom for one beam electron and its position for the next beam electron.

This justifies the approximations made in the derivation of the Debye–Waller factor

in Chapter 2.

3.8 The illumination stage: prespecimen lenses

The reader might be tempted to ask the question: why are there so many lenses

in an electron microscope? This is a relevant question, and when we compare the

early microscopes with the computer-controlled machines currently on the market

we cannot avoid noticing that the current number of lenses and correction coils is

196 The transmission electron microscope

far greater than that of the older machines. The easiest way to understand why there

are so many lenses is to analyze what each lens does in relation to its neighbors.

It is instructive to start with a microscope without lenses and to add lenses, one

at a time. We will divide the microscope column into prespecimen, specimen, and

post-specimen regions, and describe the functionality of the main lenses in each of

those regions. While the actual number of lenses for any particular microscope may

vary, we will focus in the next sections on those lenses that are present in nearly

every recent microscope model.

The illumination system of a TEM serves one important purpose: to create a beam

of electrons in a well-defined reference state (either a plane wave or a converged

fine probe). Only if we know what the reference state is can we hope to extract

information concerning the sample by analyzing the modified signal R

(recall the

discussion on page 106). It is thus important for the microscope operator to under-

stand the purpose of each of the lenses in the illumination system. This situation is

somewhat similar to that encountered when one tries to solve a differential equation:

the equation can only be completely solved if the initial conditions are specified,

and solutions may depend in a rather sensitive way on those initial conditions. We

have already seen that, in the case of the TEM, the relevant differential equation is

the stationary Schr¨odinger equation. If we wish to compare theoretical solutions to

this equation with experimental observations, we must from the beginning ensure

that both have the same initial conditions. The illumination system is, hence, of cru-

cial importance for the interpretation of experimental images based on a theoretical

description of the image formation mechanism.

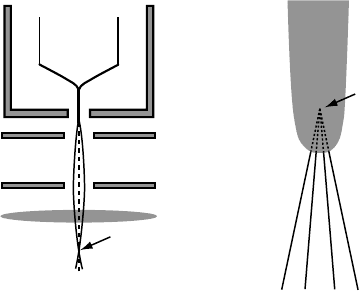

Let us consider the configuration shown in Fig. 3.26(a): an electron gun directly

illuminates a specimen, without any magnetic lenses present. This configuration

offers only limited control over the electron beam: the Wehnelt voltage or gun bias

combined with the geometry of the entire assembly determine the location and size

of the cross-over. The total number of electrons that reach any specific area on the

specimen is rather small and can be changed somewhat by adjusting the gun bias.

Since this changes the area on the filament from which electrons are emitted, the

beam brightness would also change. This is clearly an undesirable configuration

since we would like to be able to form a very fine probe on the sample surface or use

a parallel incident beam. So we decide to add a single magnetic lens, the condensor

lens C

1

, positioned close to the anode, as shown in Fig. 3.26(b).

If this lens C

1

is excited such that the image of the gun cross-over (with a

diameter of s = 10–100

µm) is formed on the specimen surface, then the size of

the smallest illuminated area (the spot size) equals sv/u, generally of the same order

of magnitude as the cross-over diameter itself. This is again undesirable because

we may wish to investigate details on a length scale of nanometers, not microns,

and this will require nanometer-sized probes.

3.8 The illumination stage: prespecimen lenses 197

S

A

W

F

Gun cross-over

diameters

(a)

S

A

W

F

u

v

C

1

C

1

a

Smallest spot

diameter = s

v

u

(b)

Fig. 3.26. (a) Prespecimen ray diagram without lenses. The gun cross-over diameter s is

10–100 µm. (b) Ray diagram with a single condensor lens C

1

. The image of the gun cross-

over is magnified by a factor v/u. The fixed aperture C

a

1

limits the angular range of electron

trajectories.

Most microscopes have a fixed aperture, the first condensor aperture C

a

1

, located

just below the lens C

1

. The purpose of this aperture is to capture electrons which

travel at large angles with respect to the optical axis and to prevent them from

hitting the inner surfaces of the subsequent lens pole pieces. This cuts down on the

number of x-rays that are generated in the column.

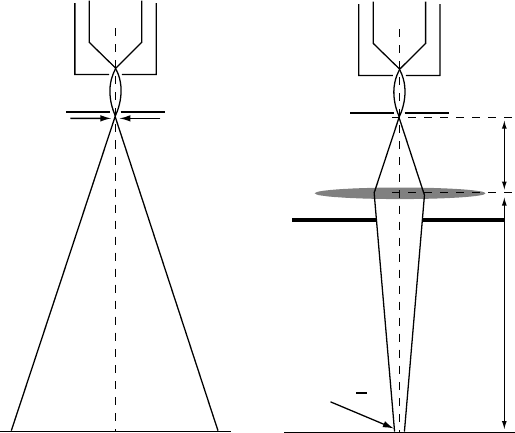

If we want the spot size on the specimen to be much smaller than the diameter

of the cross-over, then we must make v much smaller than u; this can be done

by strongly exciting the lens C

1

, as is shown in the ray diagram of Fig 3.27(a).

The stronger the excitation, the shorter the focal length will be and the smaller the

magnification factor v/u (which is then known as a demagnification factor). When

v is much smaller that u, as indicated in Fig. 3.27(a), most electrons will travel

at rather large angles with respect to the optical axis, even after passing through

C

a

1

, and we obviously need another lens to focus the beam into a small area on

the specimen. This second lens is known as C

2

(condensor 2) and it has a variable

current control and hence variable focal length.

The second condensor lens has the C

1

cross-over as its object plane, and by

varying the C

2

current we can position the conjugate image on any plane above, at,

or below the sample. If the C

2

lens current is such that the focal length is longer

than the distance from the lens center to the sample, then the lens is said to be